Evaluation by Means of Appreciation. Geographical Names As (Intangible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V E R O R D N U N G

BEZIRKSHAUPTMANNSCHAFT KLAGENFURT-LAND Bereich 4 - Forstrecht DVR Datum 01.09.2020 Zahl KL20-ALL-57/2007 (025/2020) Bei Eingaben Geschäftszahl anführen! Auskünfte Mag. Trötzmüller Michaela Waldbrandverordnung - Anordnung zur Telefon 050-536-64201 Vorbeugung von Waldbränden; Fax 050-536-64030 E-Mail [email protected] Aufhebung Seite 1 von 2 V E R O R D N U N G Die Verordnung der Bezirkshauptmannschaft Klagenfurt-Land vom 21.01.2020, Zahl: KL20-ALL-57/2007 (023/2020), über die Anordnung zur Vorbeugung von Waldbränden, wird mit sofortiger Wirkung a u f g e h o b e n. Für den Bezirkshauptmann: Mag. Trötzmüller Michaela Ergeht an: 1. die Marktgemeinde Ebenthal i.K., Miegererstraße 30, 9065 Ebenthal i.K.; *) 2. die Marktgemeinde Feistritz i. Ros., Hauptplatz 126, 9181 Feistritz i. Ros. Nr.; *) 3. die Stadtgemeinde Ferlach, Kirchgasse 5, 9170 Ferlach; *) 4. die Marktgemeinde Grafenstein, ÖR-V.-Deutschmannplatz 1, 9131 Grafenstein; *) 5. die Gemeinde Keutschach, Keutschach Nr. 1, 9074 Keutschach am See, *) 6. die Gemeinde Köttmannsdorf, Karawankenblick 1, 9071 Köttmannsdorf; *) 7. die Gemeinde Krumpendorf, Hauptstraße 145, 9201 Krumpendorf/WS; *) 8. die Gemeinde Ludmannsdorf, 9072 Ludmannsdorf Nr. 33; *) 9. die Marktgemeinde Magdalensberg, Görtschitztal Straße 135, 9064 Magdalensberg; *) 10. die Gemeinde Maria Rain, Kirchenstraße 1, 9161 Maria Rain; *) 11. die Marktgemeinde Maria Saal, Am Platz 7, 9063 Maria Saal; *) 9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee Völkermarkter Ring 19 Internet: http://www.ktn.gv.at EINE TELEFONISCHE TERMINVEREINBARUNG ERSPART IHNEN BEI VORSPRACHEN WARTEZEITEN Amtsstunden Mo-Do 7.30-16.00 Uhr, Fr 7.30-13.00 Uhr; Parteien-, Kundenverkehr Mo-Fr 8.00-12.00 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung, Dienstag ist Amtstag Austrian Anadi Bank AG IBAN: AT345200000001150383 BIC: HAABAT2K Zahl: KL20-ALL-57/2007 (025/2020) Seite: 2 von 2 12. -

Über Die Bisher in Kärnten Gefundenen Eozängerölle Von Franz KAHLER Und Adolf PAPP

©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein für Kärnten, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SRBIK, R.: Glazialgeologie der Nordseite des Karnischen Kammes. — Carinthia II, Sonderh. 6, Klagenfurt 1936. TRIMMEL, H.: Speläologisches Fachwörterbuch (Fachwörterbuch der Karst- und Höhlenkunde). — 109 S., 20 Abb., Wien (Landesverein f. Höhlenkunde) 1965. Anschrift des Verfassers: Wolfgang HOMANN, D-6100 Darmstadt, Kranichsteiner Straße 46. Über die bisher in Kärnten gefundenen Eozängerölle Von Franz KAHLER und Adolf PAPP Problemstellung Die Vorkommen eozäner Ablagerungen in Kärnten im Gebiet Guttaring und Klein St. Paul sind seit langem bekannt. Bei Guttaring (Sonnberg) und Klein St. Paul (Sittenberg) wurde eozäne Kohle abge- baut. Die Kalke des Eozäns werden am Dobranberg von der Wieters- dorfer Zementindustrie verwertet. Diese Vorkommen sind heute iso- liert. Da sie eine optimale Fossilführung mariner Organismen zeigen, besonders Foraminiferen (Assilinen, Nummuliten und Alveolinen kön- nen gesteinsbildend sein), müssen ursprünglich Verbindungen zu offe- nen Weltmeeren bestanden haben. Die ursprünglich weit verbreiteten Eozänvorkommen sind heute erodiert. Der Nachweis ihrer Existenz kann nur durch die Auffindung von Gerollen in jüngeren Ablagerun- gen erfolgen. Das Vorkommen und die Streuung derartiger Gerolle gibt somit einen wertvollen Beitrag zur Paläogeographie des Eozäns. Die erwähnten Tertiärvorkommen im Krappfeld bei Guttaring und Klein St. Paul wurden von J. van HINTE 1962 kartiert und stra- tigraphisch gegliedert. In dieser Arbeit werden fossilleere Schichten zwischen Maastricht und Eozän als Speckbauer Roter Ton bezeichnet, der im Wesentlichen das Paleozän umfaßt; Die marine Transgression setzt mit der Höhwirt — Sittenberg-Folge ein; sie umfaßt das ältere Untereozän bzw. Cuis. Höheres Untereozän bzw. Cuis und unteres Mitteleozän bzw. Lutet sind als Nummulitenkalke besonders am Do- branberg bei Klein St. -

Gemeinderats- Und Bürgermeisterwahlen 2003 Werden Auch Mit Jenen Des Jahres 1997 Verglichen

Vi IU /3> AMT DER KARNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG Landesstelle für Statistik GEMEINDERATSWAHLEN und BÜRGERMEISTERWAHLEN 2003 in KARNTEN Klagenfurt, im Dezember 2003 Auszugsweiser Abdruck nur mit Quellenangabe gestattet Herausgegeben: AMT DER KÄRNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG Landesstelle für Statistik Zusammenstellung: Winfried VALENTIN EDV-technische Durchführung: Winfried VALENTIN Mag. Evelin LEINER Titelgraphik: D.I. Wilfried KOFLER Redaktion und für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Dr. Peter IBOUNIG VORWORT Am 9. März 2003 wurden in allen 132 Kärntner Gemeinden, nach einem sechsjährigen Intervall, Gemeinderats- und Bürgermeisterwahlen abgehalten. Nachdem Kärnten als erstes österreichisches Bundesland im Jahre 1991 die Direktwahl der Bürgermeister eingeführt hatte (LGBI. Nr. 9/1991), war dies bereits die dritte Wahl, die in einem direkten Votum der Bevölkerung sowohl die Zusammensetzung des Gemeinderates als auch die Person des Bürgermeisters zum Ergebnis hatte. Jeder Wahlberechtigte bekam zwei Stimmzettel ausgehändigt, einen für die Wahl des Gemeinderates, einen zweiten für die Bürgermeisterwahl. Da in 23 Gemeinden im ersten Wahlgang die angetretenen Bürgermeisterkandidaten keine absolute Mehrheit erreichen konnten, kam es in diesen Fällen am 23. März 2003 zu einer Stichwahl zwischen den zwei stimmenstärksten Kandidaten. Neu an der Gemeinderats- und Bürgermeisterwahi des Jahres 2003 ist vor allem der Umstand, dass erstmals bei einem Urnengang in Kärnten das Wahlaiter vom vollendeten 18. auf das vollendete 16. Lebensjahr abgesenkt wurde. Diese beiden, vor sechs Jahren noch nicht zugelassenen Altersjahrgänge brachten eine Erhöhung des Wählerpotentials um rund 14.000 mit sich, die in den Absolutzahlen auch ihren entsprechenden Niederschlag finden. Die Ergebnisse der Gemeinderats- und Bürgermeisterwahlen 2003 werden auch mit jenen des Jahres 1997 verglichen. In den Detailergebnissen wird jede Gemeinde auf Grund der Fülle an Kennzahlen und Informationen auf einer Seite gesondert dargestellt. -

Mag. Rudi Vouk

Mag. Rudi Vouk let 7. člena Jahre Artikel 7 60 Years of Article 7 Avtor I Autor I Author: Mag. Rudi Vouk Prevod I Übersetzung I Translation: Prof. Mag. Jože Wakounig Frank de Boer Izdajatelj I Herausgeber I Publisher: Narodni svet koroških Slovencev I Rat der kärntner Slowenen I Council of Carinthian Slovenes Viktringer Ring 26 I a-9020 Celovec/klagenfurt Tisk I Druck I Printed by: Mohorjeva I Hermagoras I adi-dassler-gasse 4 I a-9073 Vetrinj/Viktring © 2015, Narodni svet koroških Slovencev I Rat der kärntner Slowenen I Council of Carinthian Slovenes AVSTRIJSKA DRŽAVNA POGODBA – ČLEN 7 1. Avstrijski državljani slovenske in hrvatske manjšine na Koroškem, Gradiščanskem in Štajerskem uživajo iste pravice pod enakimi pogoji kakor vsi drugi avstrijski državljani, vštevši pravico do svojih lastnih organizacij, zborovanj in tiska v svojem lastnem jeziku. 2. Avstrijski državljani slovenske in hrvatske manjšine na Koroškem, Gradiščanskem in Štajerskem imajo pravico do osnovnega pouka v slovenskem ali hrvatskem jeziku in do sorazmernega števila lastnih srednjih šol; v tej zadevi bodo šolski učni načrti pregledani in bo ustanovljen oddelek šolske nadzorne oblasti za slovenske in hrvatske šole. 3. V upravnih in sodnih okrajih Koroške, Gradiščanske in Štajerske s slovenskim, hrvatskim ali mešanim prebi - valstvom je slovenski ali hrvatski jezik dopuščen kot uradni jezik dodatno k nemškemu. V takih okrajih bodo označbe in napisi topografskega značaja prav tako v slovenščini ali hrvaščini kakor v nemščini. 4. Avstrijski državljani slovenske in hrvatske manjšine na Koroškem, Gradiščanskem in Štajerskem so udeleženi v kulturnih, upravnih in sodnih ustanovah v teh pokrajinah pod enakimi pogoji kakor drugi avstrijski državljani. -

Kaernten 2012.Indd

1B4 1C4 1 1M4 1Y4 70% 70% C M Bogen 1 A Y B 2 C M Y 70% C M Y B 3 C M Y C M C M i l i t ä r k o m m a n d o K ä r n t e n Y C M Y B Ergänzungsabteilung: 9020 KLAGENFURT am WÖRTHER SEE, 4 C M Windisch-Kaserne, Rosenbergstraße 1-3 Y 70% C M Parteienverkehr: Montag bis Freitag von 0800 bis 1400 Uhr Y B 5 C Telefon: 050201 - 0 M Y M Y C M Y C M Y B 6 STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2012 C Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001 (WG 2001), BGBl. I Nr. 146, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des M G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 1 9 9 4 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unter- ziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 1994 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stel- 7 lungskundmachung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 04.12.2012 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die Stellungskommission 4. Wehrpflichtige, die das 17. Lebensjahr vollendet haben, können sich bei der Ergänzungsabteilung des Militärkom- des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN der Stellung zugeführt. Das Stellungsverfahren, bei welchem durch den Einsatz mandos KÄRNTEN freiwillig zur vorzeitigen Stellung melden. -

Utilization of Communal Autonomy for Implementing Additional Bilingual Names of Populated Places and Streets in Carinthia (Austria)

GEGN.2/2021/71/CRP.71 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 to 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Utilization of communal autonomy for implementing additional bilingual names of populated places and streets in Carinthia (Austria) Submitted by Austria ** Summary An improved political climate between the German-speaking majority and the minority of Slovenes in the Austrian Province of Carinthia now allows the utilization of communal autonomy (a principle of the Constitution) to implement additional bilingual town signs and new bilingual street names. While that possibility always existed, implementation was not previously possible because the German-speaking majority in all bilingual communes but one would not have passed such a decision in favour of the minority. Now, the opportunity to implement bilingual place names in addition to the 164 defined in amendment No. 46/2011 to the National Minorities Act has been used by three communes in various ways. Experience has shown that the introduction of street names replacing bilingual names of populated places poses new challenges to bilingual communes. The recommendations of the Austrian Board on Geographical Names regarding the naming of urban traffic areas in 2017 (see E/CONF.105/21 and E/CONF.105/21/CRP.21) referred explicitly to the value of using field names and/or other traditional local names when applying new names. Those recommendations contributed to the conservation of traditional local place names of the minority as street names. -

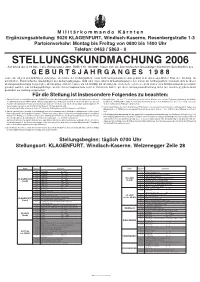

Kärnten 2006.Pmd

M i l i t ä r k o m m a n d o K ä r n t e n Ergänzungsabteilung: 9020 KLAGENFURT, Windisch-Kaserne, Rosenbergstraße 1-3 Parteienverkehr: Montag bis Freitag von 0800 bis 1400 Uhr Telefon: 0463 / 5863 - 0 STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2006 Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001, BGBl. I Nr. 146/2001, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 1 9 8 8 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unterziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 1988 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stellungskundmachung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 14.12.2006 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen wurden. Für Stellungspflichtige, welche ihren Hauptwohnsitz nicht in Österreich haben, gilt diese Stellungskundmachung nicht. Sie werden gegebenenfalls gesondert zur Stellung aufgefordert. Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die Stellungskommission 4. Wehrpflichtige, die das 17. Lebensjahr vollendet haben, können sich bei der Ergänzungsabteilung des Militär- des Militärkommandos KÄRNTEN der Stellung zugeführt. Das Stellungsverfahren, bei welchem durch den Einsatz kommandos KÄRNTEN freiwillig zur vorzeitigen Stellung melden. Sofern militärische Interessen nicht entgegen- moderner medizinischer Geräte und durch psychologische Tests die körperliche und geistige Eignung zum Wehr- stehen, wird solchen Anträgen entsprochen. dienst genau festgestellt wird, nimmt in der Regel 1 1/2 Tage in Anspruch. -

Border Crossers. 2 Border Crossers

Border crossers. 2 Border crossers. 4 5 DR. ROLAND GRILC MAG. RUDOLF VOUK Dear clients and colleagues, DR. MARIA ŠKOF dear friends of the GRILC VOUK ŠKOF Law Office Border crossers. Grenzgänger. Malo čez. This motto commemorative publication “Grenzgänger. Malo čez.” Colleagues: briefly and concisely describes what distinguishes with a series of articles on the firm's activities and its the grilc vouk škof law firm and what it stands for. most remarkable successes, as well as on everyday life Nicole Brumnik Border crossers. Grenzgänger. Malo čez. It is not only at the firm. We would like to thank all our clients for Mojca Erman, LL.M. to be understood from a geographical point of view. their trust and loyalty. We will continue to do everyt- Gisela Grilc-Kargl The grilc vouk škof law firm is active in Austria hing in our power to live up to this trust. We would Julia Grilc as well as in Slovenia and the other successor states like to thank our colleagues for their good, professi- mag. Sara Grilc, LL.M. of the former Yugoslavia. Border crossers. Grenzgänger. onal cooperation. We would like to thank all our fri- mmag. Katarina Pajnič Malo čez. It also stands for the approach with which ends for always standing by us and supported us. Our Elvina Jusufagić the grilc vouk škof law firm is tirelessly seeking special thanks also go to our former employees. They mag. Eva Maria Offner Introduction solutions to the legal problems of its clients. The ca- form an important - albeit often overlooked - pillar of mmag. -

Kärntner Ortsverzeichnis

KÄRNTNER ORTSVERZEICHNIS Gebietsstand 1.1.2014 AMT DER KÄRNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG L a n d e s s t e l l e f ü r S t a t i s t i k KÄRNTNER ORTSVERZEICHNIS Gebietsstand 1. 1. 2014 Auszugsweiser Abdruck nur mit Quellenangabe gestattet Herausgegeben: AMT DER KÄRNTNER LANDESREGIERUNG Landesstelle für Statistik Zusammenstellung: Winfried VALENTIN EDV-technische Durchführung: Winfried VALENTIN Wolfgang WEGHOFER Titelgraphik: DI Wilfried KOFLER Redaktion und für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Dr. Peter IBOUNIG V O R W O R T 2.823 Ortschaften gibt es insgesamt in unseren 132 Gemeinden. Das vorliegende „Kärntner Ortsverzeichnis“ bildet nicht nur diese Vielfalt und Vielseitigkeit ab, sondern schafft auch zahlreiche Orientierungspunkte. Der Band kann Politik und Verwaltung als Planungsgrundlage dienen und stellt darüber hinaus ein nützliches Nachschlagewerk für Bürgerinnen und Bürger dar. Das Ortsverzeichnis hat eine bereits vier Jahrzehnte lange Tradition. Man startete damit 1973, als das Land Kärnten mittels Gemeindestrukturreform die kommunale Landschaft wesentlich verbessert und die Zahl der ehemals 203 Gemeinden nahezu halbiert hatte. Seither wird es von der Landesstelle für Statistik in gewissen Zeitabständen neu aufgelegt. Die aktuelle Publikation ist bereits die zehnte dieser Reihe. Nachlesen kann man in ihr auch die aus der Registerzählung 2011 zur Verfügung stehenden Eckdaten für die einzelnen Ortschaften. Natürlich werden gemäß der jüngsten Änderung des Volksgruppengesetzes vom 26. Juli 2011 die entsprechenden Ortschaften im gemischtsprachigen Gebiet Kärntens sowohl in deutscher als auch in slowenischer Sprache ausgewiesen. An dieser Stelle möchte ich aber auch betonen, dass wir seitens der Kärntner Landesregierung die Entwicklung der Regionen, insbesondere des ländlichen Raumes, fördern und unterstützen wollen. -

Arbeitsstätten Und Beschäftigte Nach Gemeinden

Arbeitsstätten1) und Beschäftigte nach Gemeinden Mini-Registerzählung 2017 Arbeits- davon mit … unselbständig Beschäftigten Be- Politischer Bezirk stätten schäftigte ins- Gemeinde ins- 100 0 1-4 5-9 10-49 50-99 2) gesamt u.mehr gesamt Kärnten 41.581 18.793 14.543 4.028 3.562 396 259 245.530 Klagenfurt Stadt 9.497 4.064 3.375 967 877 109 105 72.502 Villach Stadt 4.808 1.932 1.779 515 470 64 48 37.042 Feldkirchen 2.186 1.023 744 222 172 16 9 10.248 Albeck 60 28 19 12 1 - - 171 Feldkirchen in Kärnten 1.102 439 390 140 114 15 4 6.480 Glanegg 99 49 32 8 7 1 2 650 Gnesau 50 23 15 7 4 - 1 367 Himmelberg 149 77 54 11 7 - - 397 Ossiach 74 35 30 4 5 - - 229 Reichenau 121 50 47 13 10 - 1 542 St.Urban 101 54 31 9 7 - - 322 Steindorf am Ossiacher See 268 141 98 13 15 - 1 813 Steuerberg 162 127 28 5 2 - - 277 Hermagor 1.352 558 538 130 114 8 4 6.357 Dellach 64 32 19 7 6 - - 249 Gitschtal 80 36 27 11 6 - - 311 Hermagor-Pressegger See 613 213 274 58 60 7 1 3.259 Kirchbach 130 65 43 11 11 - - 486 Kötschach-Mauthen 302 125 117 32 25 - 3 1.574 Lesachtal 106 56 37 8 4 1 - 309 St. Stefan im Gailtal 57 31 21 3 2 - - 169 Klagenfurt Land 4.006 2.181 1.271 291 230 24 9 14.923 Ebenthal in Kärnten 401 224 117 29 30 1 - 1.329 Feistritz im Rosental 141 62 43 15 20 1 - 784 Ferlach 480 209 179 51 34 5 2 2.894 Grafenstein 198 101 55 20 21 1 - 808 Keutschach am See 188 121 51 7 9 - - 440 Köttmannsdorf 171 101 47 15 8 - - 429 Krumpendorf am Wörthersee 360 203 117 23 13 2 2 1.272 Ludmannsdorf 86 53 23 7 2 1 - 288 Magdalensberg 201 105 63 15 16 2 - 748 Maria Rain 167 112 44 5 6 - - 361 Maria Saal 253 146 77 15 11 3 1 1.069 Maria Wörth 162 87 55 12 5 3 - 579 Moosburg 280 151 89 24 13 2 1 1.061 Poggersdorf 196 100 63 19 13 1 - 746 Pörtschach am Wörther See 344 180 131 15 14 1 3 1.178 Schiefling am Wörthersee 168 99 55 6 8 - - 392 St. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Wo Recht zu Unrecht wird, wird Widerstand zur Pflicht“ Was macht Journalismus aus politischen Strategien – eine Analyse am Beispiel der Auseinandersetzung zwischen der Kärntner Politik und dem slowenischen Interessensvertreter Rudi Vouk zur Durchsetzung der zweisprachigen Ortstafelfrage Verfasserin Sabina Zwitter-Grilc angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienbuchblatt: A 301/295 Studienrichtung lt. Studienbuchblatt: Publizistik- und Kommunikationswiss./ Gewählte Fächer statt 2. Studienrichtg. Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hausjell VORWORT ................................................................................................6 1. EINLEITUNG .........................................................................................9 2. DAS ERKENNTNISINTERESSE ......................................................... 10 2.1. Die Forschungsfragen ...................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Das theoretische Fundament.......................................................................................... 11 2.2.1. Die Kommunikationstheorien ...................................................................................... 11 2.2.2. Die analytischen Kategorien von Menz, Lalouschek und Dressler........................ 14 2.3. Narration, Dekonstruktion und Ethnisierung -

Hstnr Haltestellenname Zonen Nr. Zonenname Linien

Zonen HstNr Haltestellenname Zonenname Linien Nr. A 34201 Abtei 34105 Abtei 5338 36298 Achomitz 36770 Feistritz im Gailtal 8572 36874 Adriach Abzw 34680 Adriach - (St.Martin am Techelsberg) 5202 34708 Afritz 36212 Afritz 5150 34709 Afritz West 36212 Afritz 5150 39279 Agoritschach Dorfplatz 36761 Seltschach 8572 35817 Agsdorf 35551 St.Urban - (Glanegg) 5223 35816 Agsdorf Gegend 22 35556 St.Martin bei Feldkirchen5223 34589 Aich Abzw P Feldkirchen 34563 Oberglan 5230 5232 34138 Aich Abzw P Velden 36615 St.Egyden - (Rosegg) 5318 35686 Aich bei Hundsdorf 31255 St.Paul im Lav. 5472 20 5356 5358 5360 5364 34246 Aich Gutendorf (SV) 34453 Hörtendorf * (SV) 5368 92 33827 Aich im Jauntal Bf u 32352 Aich im Jauntal 620 35423 Aich P Bleiburg 32352 Aich im Jauntal 5420 35320 Aich P Mittertrixen 32301 Mittertrixen 5400 9594 35947 Aich P Spittal a. d. Drau 38306 Oberamlach - (Baldramsdorf) 5110 35794 Aich Weizmann 33703 Weitensfeld 5377 34790 Aichach Abzw 36318 Kreuzen 5166 35700 Aichberg Ebenbauerkreuz 31125 Thürn - (Kollegg) 5460 35705 Aichberg Klemmel 31121 Taudes - (Wois) 5460 35699 Aichberg Krampl 31125 Thürn - (Kollegg) 5460 35703 Aichberg Ort 31121 Taudes - (Wois) 5460 35701 Aichberg Rattachkreuz 31125 Thürn - (Kollegg) 5460 35702 Aichberg Sacher 31121 Taudes - (Wois) 5460 35706 Aichberg Taudes Abzw 31121 Taudes - (Wois) 5460 35704 Aichberg Umkehre 31121 Taudes - (Wois) 5460 35946 Aichfeldsiedlung 38355 Spittal 5110 35116 Aichforst Schwarzenbach 38352 Molzbichl 5121 5171 35929 Aichhorn 38908 Putschall 5002 35110 Aifersdorf 38351 Ferndorf 5171 36063 Aigen 38110 Bad Kleinkirchheim 5140 34760 Alberden Steinhauser 36323 Zlan 5160 34584 Albern 34562 Moosburg 5230 34082 Albersdorf Abzw 36622 Schiefling - (Auen) 5316 39762 Almrauschhütte 38506 Almrausch 5130 35251 Alt Glandorf Durchlaß 33551 St.Veit an der Glan 5367 5371 35250 Alt Glandorf Untermühlbach Abzw 33552 St.Donat 5371 35641 Altacherwirt Abzw 32251 St.Georgen im Lav.