The Case of Shenzhen's OCT Loft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Red Lines” Policy

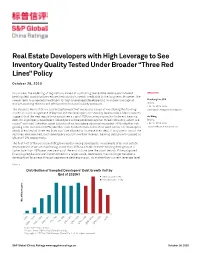

Real Estate Developers with High Leverage to See Inventory Quality Tested Under Broader “Three Red Lines” Policy October 28, 2020 In our view, the widening of regulations aimed at controlling real estate developers’ interest- ANALYSTS bearing debt would further reduce the industry’s overall credit risk in the long term. However, the nearer term may see less headroom for highly leveraged developers to finance in the capital Xiaoliang Liu, CFA market, pushing them to sell off inventory to ease liquidity pressure. Beijing +86-10-6516-6040 The People’s Bank of China said in September that measures aimed at monitoring the funding [email protected] and financial management of key real estate developers will steadily be expanded. Media reports suggest that the new regulations would see a cap of 15% on annual growth of interest-bearing Jin Wang debt for all property developers. Developers will be assessed against three indicators, which are Beijing called “red lines”: whether asset liability ratios (excluding advance) exceeded 70%; whether net +86-10-6516-6034 gearing ratio exceeded 100%; whether cash to short-term debt ratios went below 1.0. Developers [email protected] which breached all three red lines won’t be allowed to increase their debt. If only one or two of the red lines are breached, such developers would have their interest-bearing debt growth capped at 5% and 10% respectively. The first half of the year saw debt grow rapidly among developers. In a sample of 87 real estate developers that we are monitoring, more than 40% saw their interest-bearing debt grow at a faster rate than 15% year over year as of the end of June (see the chart below). -

China's Technology Mega-City an Introduction to Shenzhen

AN INTRODUCTION TO SHENZHEN: CHINA’S TECHNOLOGY MEGA-CITY Eric Kraeutler Shaobin Zhu Yalei Sun May 18, 2020 © 2020 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP SECTION 01 SHENZHEN: THE FIRST FOUR DECADES Shenzhen Then and Now Shenzhen 1979 Shenzhen 2020 https://www.chinadiscovery.com/shenzhen-tours/shenzhen-visa-on- arrival.html 3 Deng Xiaoping: The Grand Engineer of Reform “There was an old man/Who drew a circle/by the South China Sea.” - “The Story of Spring,” Patriotic Chinese song 4 Where is Shenzhen? • On the Southern tip of Central China • In the south of Guangdong Province • North of Hong Kong • Along the East Bank of the Pearl River 5 Shenzhen: Growth and Development • 1979: Shenzhen officially became a City; following the administrative boundaries of Bao’an County. • 1980: Shenzhen established as China’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ). – Separated into two territories, Shenzhen SEZ to the south, Shenzhen Bao-an County to the North. – Initially, SEZs were separated from China by secondary military patrolled borders. • 2010: Chinese State Council dissolved the “second line”; expanded Shenzhen SEZ to include all districts. • 2010: Shenzhen Stock Exchange founded. • 2019: The Central Government announced plans for additional reforms and an expanded SEZ. 6 Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone (2010) 2010: Shenzhen SEZ expanded to include all districts. 7 Regulations of the Special Economic Zone • Created an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” • -

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018 Xiaoqing Kong Master of Architecture Design A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Shenzhen, one of the fastest growing cities in the world, is the benchmark of China’s new generation of cities. As the pioneer of the economic reform, Shenzhen has developed from a small border town to an international metropolis. Shenzhen government solved the housing demand of the huge population, thereby transforming Shenzhen from an immigrant city to a settled city. By studying Shenzhen’s housing development in the past 40 years, this thesis argues that housing development is a process of competition and cooperation among three groups, namely, the government, the developer, and the buyers, constantly competing for their respective interests and goals. This competing and cooperating process is dynamic and needs constant adjustment and balancing of the interests of the three groups. Moreover, this thesis examines the means and results of the three groups in the tripartite competition and cooperation, and delineates that the government is the dominant player responsible for preserving the competitive balance of this tripartite game, a role vital for housing development and urban growth in China. In the new round of competition between cities for talent and capital, only when the government correctly and effectively uses its power to make the three groups interacting benignly and achieving a certain degree of benefit respectively can the dynamic balance be maintained, thereby furthering development of Chinese cities. -

A Data-Driven Urban Metro Management Approach for Crowd Density Control

Hindawi Journal of Advanced Transportation Volume 2021, Article ID 6675605, 14 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6675605 Research Article A Data-Driven Urban Metro Management Approach for Crowd Density Control Hui Zhou ,1 Zhihao Zheng ,2 Xuekai Cen ,1 Zhiren Huang ,1 and Pu Wang 1 1School of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, Rail Data Research and Application Key Laboratory of Hunan Province, Central South University, Changsha 410000, China 2Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics, McGill University, Montreal H3A 0C3, Quebec, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Pu Wang; [email protected] Received 9 November 2020; Revised 1 March 2021; Accepted 17 March 2021; Published 31 March 2021 Academic Editor: Yajie Zou Copyright © 2021 Hui Zhou et al. +is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Large crowding events in big cities pose great challenges to local governments since crowd disasters may occur when crowd density exceeds the safety threshold. We develop an optimization model to generate the emergent train stop-skipping schemes during large crowding events, which can postpone the arrival of crowds. A two-layer transportation network, which includes a pedestrian network and the urban metro network, is proposed to better simulate the crowd gathering process. Urban smartcard data is used to obtain actual passenger travel demand. +e objective function of the developed model minimizes the passengers’ total waiting time cost and travel time cost under the pedestrian density constraint and the crowd density constraint. -

Exploring the Brand Image of Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol.6, No.18, 2014 Exploring the brand image of Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise Zhu Mingfang 1 Wangqian 1* Bai Yangxu 2 1. Shenzhen Tourism College of Jinan University, 6 OCT East Street, Shenzhen 518053, China 2. School of Hotel and Tourism Management, the HK Polytechnic University 17 Science Museum Rd, Hong Kong, 999077 * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Adopting Aaker’s(1996) framework, this study explored the effect of Micro-blogging marketing in brand image, with the cases of two popular theme parks in Guangdong province, namely Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise. Brand image is an overall perception about the brand or the product from customer’s perspective. Most scholars and pioneers in marketing consider the success of certain product or service relies more on the brand image, rather than the physical characteristics or specific functions (Aaker, 1991). Brand identity is the one way to achieve company’s expectation, on the basis of which, the brand image could be built. This study applied the brand assessment model, and revealed the brand images of these two theme parks on the basis of brand identity model. Results of analysis indicated that both theme parks’ promotion messages emphasized their brand images. However, Happy Valley’s public relations efforts were more successful than Chimelong Paradise in transferring projected brand image to its Micro-blogging fans. Keywords: B rand image, Brand identity, Theme park, Micro-blogging 1. Introduction Tourist attractions are one of the most important parts of tourism industry. -

The Way for a Super Complex to Make a City More Convenient and Beautiful

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Way for a Super Complex to Make a City More Convenient and Beautiful Authors: Hang Xu, Chairman, Parkland Real Estate Development Co., Ltd Marianne Kwok, Principal, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates Subjects: Architectural/Design Urban Design Keywords: Connectivity Design Process Human Scale Master Planning Mixed-Use Urban Planning Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: Cities to Megacities: Shaping Dense Vertical Urbanism Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Hang Xu; Marianne Kwok The Way for a Super Complex to Make a City More Convenient and Beautiful | 超级综合体如何让城市更便利更美好 Abstract | 摘要 Hang Xu | 徐航 Chairman | 董事长 Today’s super high-rise buildings not only present the height of buildings, but also play more Parkland Real Estate Development important roles of integrating into the development of cities, coexisting with them, promoting 深圳市鹏瑞地产开发有限公司 the efficiency of them and enhancing regional value to a certain degree. Based on the case study Shenzhen, China | 深圳,中国 of One Shenzhen Bay, this paper shows how the project maximizes the value of the city. This includes 1) how the complex form makes the city more intensive, and 2) how it influences the Xu Hang is Chairman of Shenzhen Parkland Investment Group cosmopolitan way of life in the city. Co. Ltd.; Founder & Chairman of Mindray Medical International Limited (listed on the NYSE, code MR); Honorary Chairman of the Shenzhen General Chamber of Commerce; Chairman of Keywords: Urban Planning, Connectivity, Design Process, Human Scale, Master Planning, the Federation of Shenzhen Industries; Executive Vice President Mixed-Use of the Shenzhen Harmony Club; Guest Professor at Tsinghua University; and Director of the Shenzhen Contemporary Art and Urban Planning Board. -

Urban Development in China: a Regional Development Model with Challenges And

Financial and Economic Review, Vol. 19 Issue 4, December 2020, 140–144. Urban Development in China: A Regional Development Model with Challenges and... Milestones* Bence Varga Juan Du: The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City Harvard University Press, 2020, p. 384. ISBN: 978-0674975286 Hungarian translation: A sencseni kísérlet – A kínai „azonnali város” története Pallas Athéné Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 2020, p. 440. ISBN: 978-615-5884-90-0 Ever since cities have existed, urban development has been a constant challenge and required the continuous commitment of city management and city planners. Developments usually appear not as isolated phenomena: most of the times they should be viewed within the framework of a (geopolitical, economic or social) context. Challenges in this respect are posed particularly by periods of post-war reconstruction or economic downturn. Thus, we also need to know the history of the respective city or region to be able to put the urban development proposals, the relevant debates and courses of action into a proper context. In the absence of this, we can easily make the error of assessing the circumstances of the development of contemporary towns incorrectly. We may face exactly this mistake when assessing the rise of Shenzhen. According to the “myth of Shenzhen”, the success of the city is primarily attributable to the economic opening of China and modern city planning as well as to the circumstance that Shenzhen has no major historical past, and thus during the planning of the city it was not necessary to take into consideration traditions or previously developed expectations, which otherwise could have represented constraints. -

Overseas Chinese Town (Asia) Holdings Limited

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt about this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your licensed securities dealer or other registered dealer in securities, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Overseas Chinese Town (Asia) Holdings Limited (the “Company”), you should at once hand this circular with the enclosed form of proxy to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or the transferee. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. Overseas Chinese Town (Asia) Holdings Limited (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 03366) RENEWAL OF GENERAL MANDATES, TO ISSUE NEW SHARES AND REPURCHASE SHARES, PROPOSED RE-ELECTION OF RETIRING DIRECTORS AND NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Capitalised terms used in this cover page shall bear the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in this circular. A notice convening the AGM of the Company to be held on Friday, 21 May 2021 at 11:00 a.m. at the conference room of the Company at 3/F., Jacaranda IBC, OCT Harbour, Baishi Road, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, PRC is set out on pages 16 to 20 of this circular. -

Shenzhen Attractions 2 About and Plan Your Future Visits to China? for More Information Visit the Splendid China and Chinese Folk Culture Village Website

Shenzhen Visitors Guides www.discoverchina.info Guide 2: Attractions Shenzhen is a modern and beautiful metropolis located in southern China just across the border from Hong Kong, and it’s a great place to start your exploration of China. This Guide profiles Shenzhen's many attractions, which include: Theme parks offering family fun and fascinating cultural experiences. Beautiful parks, natural areas and beaches and interesting historic sites. Golf, tennis and yachting with world-class venues and facilities. Excellent shopping, accommodation and dining. The 26th Universiade games 2011. For an introduction to Shenzhen, see Shenzhen Visitors Guides, Guide 1: About Shenzhen, and to plan a visit see Shenzhen Visitors Guides, Guide 3: Plan Your Visit. Theme Parks Overseas Chinese Town Shenzhen’s Nanshan District features the Window of the World, Splendid China, Chinese Folk Culture Village and Happy Kingdom theme parks clustered together in an area known as Overseas Chinese Town (OCT). OCT also features hotels and other tourist facilities. Window of the World Experience the world's landmarks in the one day. Over 130 detailed miniature replicas of notable landmarks throughout the world are featured in eight international areas, including the pyramids of Egypt, a 1/3 scale Eiffel Tower, Buckingham Palace, Niagara Falls and the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Opera House. There are also cultural performances from around the world, and several fun rides. Splendid China Over 80 notable landmarks from around China can be experienced in miniature in the one location, including the Forbidden City, the Terracotta Army and the Great Wall. There are also cultural performances. What better place to think © January 2011 (Edition 4). -

The Making of Innovation in Shenzhen

International review for spatial planning and sustainable development, Vol.4 No.4 (2016), 27-41 ISSN: 2187-3666 (online) DOI: 4http://dx.doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.4.4_27 Copyright@SPSD Press from 2010, SPSD Press, Kanazawa The Open Innovation Paradigm: from Outsourcing to Open-sourcing in Shenzhen, China Valérie Fernandez1, Gilles Puel2*, Clément Renaud1 1 Telecom ParisTech, UMR I3 2 University de Toulouse, LEREPS * Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected] Received: March 02, 2016; Accepted: May 30, 2016 Key words: Open innovation, New urban places, Makers, shanzhai, Shenzhen Abstract: Having once been the headquarters of ‘Made in China,’ Shenzhen’s industry is currently undergoing profound change. The appearance of new urban places for technological innovation is reviving the ageing industrial processes of this manufacturing city. It is supposed to transform Shenzhen into the Silicon Valley of hardware. Two groups, one local, the shanzhai community made up of entrepreneurs and companies historically based on a strategy of imitating high- end products, and the other, a more international maker community, are thought to be the main drivers of this change using values of ‘open innovation’. The building of this ecosystem relies largely on practices associated with being open-source. Like in California, open innovation contributed to the creation of resources for the development of a vast high-tech industry. This ethnographic field study shows how, while both communities, the international makers and the shanzhai, draw on open innovation, they do not have the same values. For the shanzhai, open innovation means total deregulation and a kind of coopetition that poorly masks fierce competition. -

Sinolink Securities (Hong Kong) Company Limited 1/12/2016 1 長和 70% 2 中電控股 70% 3 香港中華煤氣 70% 4 九龍倉集團 70% 5 匯豐控股 70% 6 電能實業 70% 7 Hoifu Energy Group Ltd

Sinolink Securities (Hong Kong) Company Limited 1/12/2016 1 長和 70% 2 中電控股 70% 3 香港中華煤氣 70% 4 九龍倉集團 70% 5 匯豐控股 70% 6 電能實業 70% 7 Hoifu Energy Group Ltd. 20% 8 電訊盈科 60% 9 NINE EXPRESS LTD 20% 10 恒隆集團 60% 11 恒生銀行 70% 12 恒基地產 70% 14 希慎興業 60% 15 Vantage International (Holdings) Ltd. 50% 16 新鴻基地產 70% 17 新世界發展 70% 18 Oriental Press Group Ltd. 15% 19 太古股份公司A 70% 20 會德豐 60% 22 Mexan Ltd. 15% 23 東亞銀行 70% 25 Chevalier International Holdings Ltd. 20% 26 China Motor Bus Co., Ltd. 25% 27 銀河娛樂 70% 28 TIAN AN CHINA INVESTMENTS CO LTD 40% 29 Dynamic Holdings Ltd. 40% 31 China Aerospace International Holdings Ltd. 55% 32 Cross-Harbour (Holdings) Ltd., The 35% 33 Asia Investment Finance Group Ltd. 15% 34 Kowloon Development Co. Ltd. 40% 35 Far East Consortium International Ltd. 50% 38 第一拖拉機股份 50% 39 China Beidahuang Industry Group Holdings Ltd. 10% 41 Great Eagle Holdings Ltd. 60% 42 Northeast Electric Development Co. Ltd. - H Shares 40% 43 C.P. POKPHAND 40% 44 Hong Kong Aircraft Engineering Co. Ltd. 45% 45 Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels, Ltd., The 40% 46 Computer And Technologies Holdings Ltd. 15% 47 Hop Hing Group Holdings Ltd. 15% 48 China Automotive Interior Decoration Holdings Ltd. 20% 50 Hong Kong Ferry (Holdings) Co. Ltd. 35% 51 Harbour Centre Development Ltd. 15% 52 Fairwood Holdings Ltd. 55% 53 GUOCO GROUP 40% 54 合和實業 60% 55 NEWAY GROUP HOLDINGS LTD 20% 56 Allied Properties (HK) Ltd. 35% 57 Chen Hsong Holdings Ltd. 10% 58 Sunway International Holdings Ltd. -

Shenzhen, China

5th meeting of FG ML5G (5, 7-8 March 2019) and workshop on "Towards a New Era – AI in 5G" (6 March 2019), Shenzhen, China Practical information for participants 1 Workshop and Meeting venue Name: St.Helen Hotel 博林圣海伦酒店 (The website of the hotel and Google maps refer to the hotel as “Novotel Shenzhen Bauhinia Hotel”) Address: No 2002, East Qiancheng Road, Nanshan Science and Technology Park, Shenzhen, China Website: http://www.helenshenzhen.cn/en 2 Getting to Workshop/Meeting venue From Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport (cost to be included) Taxi from Shenzhen airport (30km, 100 CNY) From Hongkong International Airport (cost to be included) Shuttle to Lok Ma Chau (Huanggang) Port from HK airport (http://www.hongkongairport.com/en/transport/mainland-connection/mainland-coaches) Taxi to hotel from Lok Ma Chau (Huanggang) Port (12km, 40CNY) Public transport (From Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport) Subway Line 11 to Chegongmiao Station (Direction: Futian, 7 stops) Transfer subway line 1 to Qiaocheng East Station (Direction: Airport east, 2 stops) 3 Local Host Focal Point: Name: Ms. Liya Yuan Email: [email protected] Phone: +86- 15205163004 4 Recommended Hotels near the event Venue Participants are in charge of their own transportation and booking of accommodation. Name: St. Helen Hotel 博林圣海伦酒店 (0km) (The website of the hotel and Google maps refer to the hotel also as “Novotel Shenzhen Bauhinia Hotel”) Address: No 2002, East Qiancheng Road, Nanshan Science and Technology Park, Shenzhen, China 深圳市侨城东路2002号 Website: http://www.helenshenzhen.cn/en email:[email protected] Please send email for room reservation.