Urban Development in China: a Regional Development Model with Challenges And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Red Lines” Policy

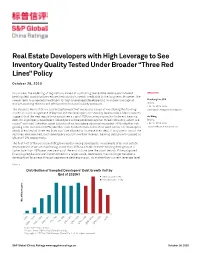

Real Estate Developers with High Leverage to See Inventory Quality Tested Under Broader “Three Red Lines” Policy October 28, 2020 In our view, the widening of regulations aimed at controlling real estate developers’ interest- ANALYSTS bearing debt would further reduce the industry’s overall credit risk in the long term. However, the nearer term may see less headroom for highly leveraged developers to finance in the capital Xiaoliang Liu, CFA market, pushing them to sell off inventory to ease liquidity pressure. Beijing +86-10-6516-6040 The People’s Bank of China said in September that measures aimed at monitoring the funding [email protected] and financial management of key real estate developers will steadily be expanded. Media reports suggest that the new regulations would see a cap of 15% on annual growth of interest-bearing Jin Wang debt for all property developers. Developers will be assessed against three indicators, which are Beijing called “red lines”: whether asset liability ratios (excluding advance) exceeded 70%; whether net +86-10-6516-6034 gearing ratio exceeded 100%; whether cash to short-term debt ratios went below 1.0. Developers [email protected] which breached all three red lines won’t be allowed to increase their debt. If only one or two of the red lines are breached, such developers would have their interest-bearing debt growth capped at 5% and 10% respectively. The first half of the year saw debt grow rapidly among developers. In a sample of 87 real estate developers that we are monitoring, more than 40% saw their interest-bearing debt grow at a faster rate than 15% year over year as of the end of June (see the chart below). -

Annual Report 2020

CONTENTS CONTENTS 2 Company Profile 3 Corporate Information 4 Chairman’s Statement 10 2020 Highlights 14 Biographies of Directors and Senior Management 19 Management Discussion and Analysis 32 Report of Corporate Governance 57 Directors’ Report 79 Independent Auditor’s Report 86 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 88 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 89 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 91 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 92 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 94 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 179 Five-year Financial Summary 180 Information for Investors 181 Definitions COMPANY PROFILE Beijing Energy International Holding Co., Ltd. | Annual Report 2020 COMPANY PROFILE Beijing Energy International Holding Co., Ltd. (listed on the main board of the Stock Exchange) is striving to be a leading global eco-development solutions provider, which mainly engaged in the development, investment, operation and management of solar power plants and other renewable energy projects. As of 31 December 2020, the Group owned 61 solar power plants with aggregate installed capacity of approximately 2,070.4MW, and have generated approximately 2,795,834MWh of green electricity for the entire 2020. Our power plant network covers various provinces/autonomous regions including Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shanxi, Xinjiang and Guangdong, etc. Under the rapid growth of the renewable energy industry, the Company has attracted many strong investors, including BEH (an integrated energy service enterprise of Beijing City), CMNEG under CMG, China Huarong (one of the four major asset management companies in China), QCCI (a state-owned enterprise) and ORIX (an international large-scale group providing integrated financial services). The Group aims at building the most efficient and advanced renewable energy operation and maintenance platform, and establishing a green ecosphere by employing a low-carbon and sustainable development model, so as to bring clean energy into millions of families. -

China's Technology Mega-City an Introduction to Shenzhen

AN INTRODUCTION TO SHENZHEN: CHINA’S TECHNOLOGY MEGA-CITY Eric Kraeutler Shaobin Zhu Yalei Sun May 18, 2020 © 2020 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP SECTION 01 SHENZHEN: THE FIRST FOUR DECADES Shenzhen Then and Now Shenzhen 1979 Shenzhen 2020 https://www.chinadiscovery.com/shenzhen-tours/shenzhen-visa-on- arrival.html 3 Deng Xiaoping: The Grand Engineer of Reform “There was an old man/Who drew a circle/by the South China Sea.” - “The Story of Spring,” Patriotic Chinese song 4 Where is Shenzhen? • On the Southern tip of Central China • In the south of Guangdong Province • North of Hong Kong • Along the East Bank of the Pearl River 5 Shenzhen: Growth and Development • 1979: Shenzhen officially became a City; following the administrative boundaries of Bao’an County. • 1980: Shenzhen established as China’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ). – Separated into two territories, Shenzhen SEZ to the south, Shenzhen Bao-an County to the North. – Initially, SEZs were separated from China by secondary military patrolled borders. • 2010: Chinese State Council dissolved the “second line”; expanded Shenzhen SEZ to include all districts. • 2010: Shenzhen Stock Exchange founded. • 2019: The Central Government announced plans for additional reforms and an expanded SEZ. 6 Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone (2010) 2010: Shenzhen SEZ expanded to include all districts. 7 Regulations of the Special Economic Zone • Created an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” • -

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018

Dwelling in Shenzhen: Development of Living Environment from 1979 to 2018 Xiaoqing Kong Master of Architecture Design A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Shenzhen, one of the fastest growing cities in the world, is the benchmark of China’s new generation of cities. As the pioneer of the economic reform, Shenzhen has developed from a small border town to an international metropolis. Shenzhen government solved the housing demand of the huge population, thereby transforming Shenzhen from an immigrant city to a settled city. By studying Shenzhen’s housing development in the past 40 years, this thesis argues that housing development is a process of competition and cooperation among three groups, namely, the government, the developer, and the buyers, constantly competing for their respective interests and goals. This competing and cooperating process is dynamic and needs constant adjustment and balancing of the interests of the three groups. Moreover, this thesis examines the means and results of the three groups in the tripartite competition and cooperation, and delineates that the government is the dominant player responsible for preserving the competitive balance of this tripartite game, a role vital for housing development and urban growth in China. In the new round of competition between cities for talent and capital, only when the government correctly and effectively uses its power to make the three groups interacting benignly and achieving a certain degree of benefit respectively can the dynamic balance be maintained, thereby furthering development of Chinese cities. -

A Data-Driven Urban Metro Management Approach for Crowd Density Control

Hindawi Journal of Advanced Transportation Volume 2021, Article ID 6675605, 14 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6675605 Research Article A Data-Driven Urban Metro Management Approach for Crowd Density Control Hui Zhou ,1 Zhihao Zheng ,2 Xuekai Cen ,1 Zhiren Huang ,1 and Pu Wang 1 1School of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, Rail Data Research and Application Key Laboratory of Hunan Province, Central South University, Changsha 410000, China 2Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics, McGill University, Montreal H3A 0C3, Quebec, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Pu Wang; [email protected] Received 9 November 2020; Revised 1 March 2021; Accepted 17 March 2021; Published 31 March 2021 Academic Editor: Yajie Zou Copyright © 2021 Hui Zhou et al. +is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Large crowding events in big cities pose great challenges to local governments since crowd disasters may occur when crowd density exceeds the safety threshold. We develop an optimization model to generate the emergent train stop-skipping schemes during large crowding events, which can postpone the arrival of crowds. A two-layer transportation network, which includes a pedestrian network and the urban metro network, is proposed to better simulate the crowd gathering process. Urban smartcard data is used to obtain actual passenger travel demand. +e objective function of the developed model minimizes the passengers’ total waiting time cost and travel time cost under the pedestrian density constraint and the crowd density constraint. -

An Adapted Geographically Weighted Lasso (Ada-GWL) Model For

An Adapted Geographically Weighted Lasso (Ada-GWL) model for estimating metro ridership Yuxin He∗1, Yang Zhaoy2 and Kwok Leung Tsuiz1,2 1School of Data Science, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong 2Centre for Systems Informatics Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong April 3, 2019 Abstract Ridership estimation at station level plays a critical role in metro transportation planning. Among various existing ridership estimation methods, direct demand model has been recognized as an effective approach. However, existing direct demand models including Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) have rarely included local model selection in ridership estimation. In practice, acquiring insights into metro ridership under multiple influencing factors from a local perspective is important for passenger volume management and transportation planning operations adapting to local conditions. In this study, we propose an Adapted Geographi- cally Weighted Lasso (Ada-GWL) framework for modelling metro ridership, which performs regression-coefficient shrinkage and local model selection. It takes metro network connection intermedia into account and adopts network-based distance metric instead of Euclidean-based distance metric, making it so-called adapted to the context of metro networks. The real-world arXiv:1904.01378v1 [stat.AP] 2 Apr 2019 case of Shenzhen Metro is used to validate the superiority of our proposed model. The results show that the Ada-GWL model performs the best compared with the global model (Ordinary Least Square (OLS), GWR, GWR calibrated with network-based distance metric and GWL in terms of estimation error of the dependent variable and goodness-of-fit. Through understanding the variation of each coefficient across space (elasticities) and variables selection of each station, ∗email: [email protected] yCorresponding author, email: [email protected] zemail: [email protected] 1 it provides more realistic conclusions based on local analysis. -

Exploring the Brand Image of Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol.6, No.18, 2014 Exploring the brand image of Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise Zhu Mingfang 1 Wangqian 1* Bai Yangxu 2 1. Shenzhen Tourism College of Jinan University, 6 OCT East Street, Shenzhen 518053, China 2. School of Hotel and Tourism Management, the HK Polytechnic University 17 Science Museum Rd, Hong Kong, 999077 * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Adopting Aaker’s(1996) framework, this study explored the effect of Micro-blogging marketing in brand image, with the cases of two popular theme parks in Guangdong province, namely Shenzhen Happy Valley and Chimelong Paradise. Brand image is an overall perception about the brand or the product from customer’s perspective. Most scholars and pioneers in marketing consider the success of certain product or service relies more on the brand image, rather than the physical characteristics or specific functions (Aaker, 1991). Brand identity is the one way to achieve company’s expectation, on the basis of which, the brand image could be built. This study applied the brand assessment model, and revealed the brand images of these two theme parks on the basis of brand identity model. Results of analysis indicated that both theme parks’ promotion messages emphasized their brand images. However, Happy Valley’s public relations efforts were more successful than Chimelong Paradise in transferring projected brand image to its Micro-blogging fans. Keywords: B rand image, Brand identity, Theme park, Micro-blogging 1. Introduction Tourist attractions are one of the most important parts of tourism industry. -

Etonhouse Opens in Shenzhen, Its 40Th Campus in China

EtonHouse opens in Shenzhen, its 40th campus in China The first Singapore based group to open in Shenzhen, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the economic reform process in China Shenzhen, China, December 2018- The EtonHouse International Education Group opened its first pre-school campus in Shenzhen, making it the 40th EtonHouse campus in China. The Group set up its first campus in 2003 in Suzhou and is now present in 28 Chinese cities and has 7500 students in China alone. EtonHouse is also the only Singapore based education provider to establish its presence in Shenzhen. Located near the Overseas China Town (OCT) Tencent and High Technology Park, in the heart of Nanshan District, Shenzhen, the boutique campus covers an area of over 2,500 square meters and has a capacity of 250 students. The pre-school caters to students from 2- 6 years of age has many unique and innovative features such as a spacious playground, rooftop garden, a children’s kitchen, a light studio and performing and visual art spaces. These learning spaces encourage children to explore creative play and inquiries in a child- responsive environment. The EtonHouse international inquiry based curriculum ‘Inquire Think Learn’ will be delivered in this campus in a dual language environment offered in English and Chinese. The philosophy is inspired by the globally renowned pedagogy of Reggio Emilia, a teaching project from Italy. The EtonHouse curriculum, successful in more than 12 countries and 100 campuses is international in its approach but connected to the local community in the way that it is delivered, thus offering a wonderful blend of the East and the West. -

The 35Th Chinese Control Conference (CCC2016)

The 35th Chinese Control Conference (CCC2016) he 35th Chinese Control Confer- Shik Hong, vice-president of ACA; Prof. States, and the former Yugoslavia. After ence (CCC2016) was held on July Yoshito Ohta, vice-president of SICE; a rigorous peer review process orga- T 27–29, 2016 at the Chengdu Inter- Prof. Dongil Cho, president-elect of nized by the conference program com- national Conference Center, Chengdu, ICROS; and more than 100 consultants mittee, 1944 papers were accepted and Sichuan Province, China. Chengdu is and committee members of the TCCT. included in the conference proceedings. one of the most attractive cities and a The proceedings will be included in the major metropolis in China. The city, Technical Program IEEE conference publication program with its rich historical heritage and This year, 2901 papers were submitted with the IEEE catalog number CFP1640A. natural pride, is renowned for its cui- to CCC2016 with authors from 29 coun- Seven distinguished scientists de- sine, tourism, culture, and the giant tries and regions including Australia, livered plenary lectures: panda. Chengdu is the first Asian city Canada, China, Comoros, Ecuador, Fin- » “Universal Laws and Architec- to win a UNESCO City of Gastronomy land, France, Germany, Hong Kong, tures for Bio, Med, Neuro, and accolade, one of only six in the world. India, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Tech Nets,” by John Doyle, Cali- Over 2300 people attended the confer- Mexico, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, fornia Institute of Technology, ence, including more than 2000 regis- Romania, Russia, Serbia and Montene- United States trants, 50 faculty and staff volunteers, gro, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, » “Automation of High-Speed Rail- and over 200 student volunteers from Taiwan, the United Arab Emirates, way Traction Power Supply Sys- Southwest Jiaotong University. -

An Anthropological Study of a City Thoroughfare

Between promises and uncertainties: an anthropological study of a city thoroughfare A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Ximin Zhou Social Anthropology | School of Social Sciences Table of Contents List of figures .................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Copyright statement ...................................................................................................................... 7 A note on language and the Chinese administrative division ......................................... 8 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 9 Glossary ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... -

Handshake 302 Is a Repurposed, 12.5 M2 Efficiency Apartment on the Third Floor of a Stereotypic “Hand- Shake Building”

HANDSHAKE 302 ART CENTER REDEFINING URBAN POSSIBILITY THROUGH CREATIVE ENGAGEMENT 深圳市福田区益田路3008号皇都广场B座1108室 Rm 1108, Bldg B, Huangdu Plaza, 3008 Yitian Rd, Futian Dist, Shenzhen City +86 136 3260 7582 [email protected] Handshake 302 is a repurposed, 12.5 m2 efficiency apartment on the third floor of a stereotypic “hand- shake building”. Throughout Shenzhen, teenage mi- grants, recent college graduates, and working class families live in densely populated urbanized villages. Baishizhou, for example, has an area of .6 km2 and an estimated population of 140,000 residents, bring- ing the population density to almost 280,000 per square kilometer. Of course, any one of Baishizhou’s 2,340 buildings is a multi-story building, with a floor area ratio that falls between 2 and 12. These build- ings are packed so tightly together that it is pos- sibly to reach out one’s window and shake hands with the neighbor. Handshake 302 projects exploit the semiotic discrepancies between “art space” and “low cost housing” to provide an accessible sociology of Baishizhou. AWARDS 2016 Handshake 302, One Foundation, Social Innovation, Tencent Corporation 2015 Handshake 302, Comprehensive Creativity, Shenzhen Qicai Awards for Design HANDSHAKE 302 PROJECTS Handshake 302 was designated a collatoral exhibition, Shenzhen-Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, 2015 and 2013. 2016-present Handshake 302 Village Artist Residency 2015 Handshake with the Future 2015 My White Wall Compulsions 2014 白鼠笔记/Village Hack 2014 Paper Crane Tea 2013 Accounting CURATORIAL EXPERIENCE 2016 Art Sprouts, P+V Gallery Dalang 2015 “Youth”, mural at the Dalang Dream Center Dormitory for migrant workers. -

Urban Redevelopment in Shenzhen, China Neoliberal Urbanism, Gentrification, and Everyday Life in Baishizhou Urban Village

DEGREE PROJECT IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2019 Urban Redevelopment in Shenzhen, China Neoliberal Urbanism, Gentrification, and Everyday Life in Baishizhou Urban Village JOHAN BACKHOLM KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT Urban Redevelopment in Shenzhen, China Neoliberal Urbanism, Gentrification, and Everyday Life in Baishizhou Urban Village JOHAN BACKHOLM Master’s Thesis. AG212X Degree Project in Urban and Regional Planning, Second Cycle, 30 credits. Master’s Programme in Sustainable Urban Planning and Design, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Supervisor: Kyle Farrell. PhD Fellow, Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Department of Urban Planning and Environment, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Examiner: Andrew Karvonen. Associate Professor, Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Department of Urban Planning and Environment, School of Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Author contact: [email protected] Stockholm 2019 Abstract Urban redevelopment is increasingly used as a policy tool for economic growth by local governments in Chinese cities, which is taking place amid rapid urbanization and in an expanding globalized economy. Along with the spatial transformation, urban redevelopment often entails socioeconomic change in the form of processes of gentrification,