Ornithodoros Moubata (Acari: Argasidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

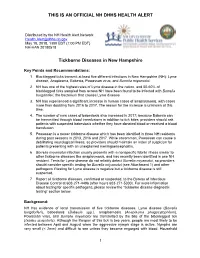

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Bitten Enhance.Pdf

bitten. Copyright © 2019 by Kris Newby. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales pro- motional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Frontispiece: Tick research at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, in Hamilton, Mon- tana (Courtesy of Gary Hettrick, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], National Institutes of Health [NIH]) Maps by Nick Springer, Springer Cartographics Designed by William Ruoto Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Newby, Kris, author. Title: Bitten: the secret history of lyme disease and biological weapons / Kris Newby. Description: New York, NY: Harper Wave, [2019] Identifiers: LCCN 2019006357 | ISBN 9780062896278 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Lyme disease— History. | Lyme disease— Diagnosis. | Lyme Disease— Treatment. | BISAC: HEALTH & FITNESS / Diseases / Nervous System (incl. Brain). | MEDICAL / Diseases. | MEDICAL / Infectious Diseases. Classification: LCC RC155.5.N49 2019 | DDC 616.9/246—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006357 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Appendix I: Ticks and Human Disease Agents -

Tick-Borne Diseases in Maine a Physician’S Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC Photo)

tick-borne diseases in Maine A Physician’s Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC PHOTO) Nymph Nymph Nymph Adult Male Adult Male Adult Male Adult Female Adult Female Adult Female images not to scale know your ticks Ticks are generally found in brushy or wooded areas, near the DEER TICK DOG TICK LONESTAR TICK Ixodes scapularis Dermacentor variabilis Amblyomma americanum ground; they cannot jump or fly. Ticks are attracted to a variety (also called blacklegged tick) (also called wood tick) of host factors including body heat and carbon dioxide. They will Diseases Diseases Diseases transfer to a potential host when one brushes directly against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted Ehrlichiosis anaplasmosis, babesiosis fever and tularemia them and then seek a site for attachment. What bites What bites What bites Nymph and adult females Nymph and adult females Adult females When When When April through September in Anytime temperatures are April through August New England, year-round in above freezing, greatest Southern U.S. Coloring risk is spring through fall Adult females have a dark Coloring Coloring brown body with whitish Adult females have a brown Adult females have a markings on its hood body with a white spot on reddish-brown tear shaped the hood Size: body with dark brown hood Unfed Adults: Size: Size: Watermelon seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed suMMer fever algorithM ALGORITHM FOR DIFFERENTIATING TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN MAINE Patient resides, works, or recreates in an area likely to have ticks and is exhibiting fever, This algorithm is intended for use as a general guide when pursuing a diagnosis. -

Molecular Evidence of Babesia Infections in Spinose Ear Tick, Otobius Megnini Infesting Stabled Horses in Nuwara Eliya Racecourse: a Case Study

Ceylon Journal of Science 47(4) 2018: 405-409 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v47i4.7559 SHORT COMMUNICATION Molecular evidence of Babesia infections in Spinose ear tick, Otobius megnini infesting stabled horses in Nuwara Eliya racecourse: A case study G.C.P. Diyes1,2, R.P.V.J. Rajapakse3 and R.S. Rajakaruna1,2,* 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 2The Postgraduate Institute of Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine & Animal Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka Received:26/04/2018; Accepted:02/08/2018 Abstract: Spinose ear tick, Otobius megnini (Family Argasidae) Race Club (Joseph, 1982). There is a speculation that O. is a one-host soft tick that parasitizes domesticated animals and megnini was introduced to Sri Lanka from India via horse occasionally humans. It causes otoacariasis or parasitic otitis in trading. The first report of O. megnini in Sri Lanka is in humans and animals and also known to carry infectious agents. 2010 from stable workers and jockeys as an intra-aural Intra aural infestations of O. megnini is a serious health problem infestation (Ariyaratne et al., 2010). In Sri Lanka, O. in the well-groomed race horses in Nuwara Eliya. Otobius megnini appears to have a limited distribution with no megnini collected from the ear canal of stabled horses in Nuwara records of it infesting any other domesticated animals other Eliya racecourse were tested for three possible infections, than horses in the racecourses (Diyes and Rajakaruna, Rickettsia, Theileria and Babesia. -

20210315092550 48603.Pdf

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 24 February 2021 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.616343 Molecular Characterization and Immunological Evaluation of Truncated Babesia microti Rhoptry Neck Protein 2 as a Vaccine Candidate † † Yu chun Cai 1,2,3 , Chun li Yang 4 , Wei Hu 1,2,3,5, Peng Song 1,2,3, Bin Xu 1,2,3, Yan Lu 1,2,3, Lin Ai 1,2,3, Yan hong Chu 1,2,3, Mu xin Chen 1,2,3, Jia xu Chen 1,2,3* and Shao hong Chen1,2,3* 1 National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shanghai, China, 2 Laboratory Edited by: of Parasite and Vector Biology, Ministry of Public Health, Shanghai, China, 3 WHO Collaborating Centre for Tropical Diseases, Wanderley De Souza, National Center for International Research on Tropical Diseases, Ministry of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, 4 Department of Clinical Research, The 903rd Hospital of PLA, Hangzhou, China, 5 School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Brazil Shanghai, China Reviewed by: Junlong Zhao, Huazhong Agricultural University, Babesia microti is a protozoan that infects red blood cells. Babesiosis is becoming a new China global threat impacting human health. Rhoptry neck proteins (RONs) are proteins located Lan He, at the neck of the rhoptry and studies indicate that these proteins play an important role in Huazhong Agricultural University, China the process of red blood cell invasion. In the present study, we report on the bioinformatic *Correspondence: analysis, cloning, and recombinant gene expression of two truncated rhoptry neck Jia xu Chen proteins 2 (BmRON2), as well as their potential for incorporation in a candidate vaccine [email protected] fl Shao hong Chen for babesiosis. -

Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission Of

microorganisms Review Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission of Francisella tularensis in Ticks Brenden G. Tully and Jason F. Huntley * Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Over 600,000 vector-borne disease cases were reported in the United States (U.S.) in the past 13 years, of which more than three-quarters were tick-borne diseases. Although Lyme disease accounts for the majority of tick-borne disease cases in the U.S., tularemia cases have been increasing over the past decade, with >220 cases reported yearly. However, when comparing Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) and Francisella tularensis (causative agent of tularemia), the low infectious dose (<10 bacteria), high morbidity and mortality rates, and potential transmission of tularemia by multiple tick vectors have raised national concerns about future tularemia outbreaks. Despite these concerns, little is known about how F. tularensis is acquired by, persists in, or is transmitted by ticks. Moreover, the role of one or more tick vectors in transmitting F. tularensis to humans remains a major question. Finally, virtually no studies have examined how F. tularensis adapts to life in the tick (vs. the mammalian host), how tick endosymbionts affect F. tularensis infections, or whether other factors (e.g., tick immunity) impact the ability of F. tularensis to infect ticks. This review will assess our current understanding of each of these issues and will offer a framework for future studies, which could help us better understand tularemia and other tick-borne diseases. -

Establishment and Optimisation of Anti-Babesia Microti Drug E Cacy

Establishment and Optimisation of Anti-Babesia microti Drug Ecacy Evaluation Method Meng Yin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hao-bing Zhang ( [email protected] ) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Yi Tao Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Jun-Min Yao Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hua Liu Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Htet Htet Win Ministry of Education Jia-Xu Chen Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Le-Le Huo Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Jiang Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Yu-Fen Wei Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Qi Zheng Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cong-Shan Liu Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Jian Xue Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Qi-Qi Shi Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Methodology Page 1/20 Keywords: Babesia microti, robenidine hydrochloride, quantitative PCR, atovaquone, azithromycin, evaluation of drug ecacy Posted Date: October 15th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-90833/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/20 Abstract Background Babesiosis, an infectious zoonotic parasitic disease that occurs globally, is most commonly caused by Babesia microti. For a severe infection, a combination of exchange transfusion and support-therapy is used and, for a mild infection, single antibiotics, or a combination of antibiotics and antiprotozoal drugs, are used for 7–10 days for the treatment of babesiosis; however, as these treatments have problems, a new therapy is needed. Although aetiological and molecular biology methods are often used in drug screening, these methods have disadvantages and there is no standard anti-B. -

Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis Current Status

IgeneX_v1_A4_A4_2011 27/04/2012 17:26 Page 49 Tick-borne Infectious Disease Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis – Current Status Jyotsna S Shah,1 Richard Horowitz2 and Nick S Harris3 1. Vice President, IGeneX Inc., California; 2. Medical Director, Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center, New York; 3. CEO and President, IGeneX Inc., California, US Abstract Lyme disease (LD), caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi complex, is the most frequently reported arthropod-borne infection in North America and Europe. The ticks that transmit LD also carry other pathogens. The two most common co-infections in patients with LD are babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Human babesiosis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia including Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, Babesia divergens-like (also known as Babesia MOI), Babesia EU1 and Babesia KO1. Ehrlichiosis includes human sennetsu ehrlichiosis (HSE), human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), human ewingii ehrlichiosis (HEE) and the recently discovered human ehrlichiosis Wisconsin–Minnesota (HWME). The resulting illnesses vary from asymptomatic to severe, leading to significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Clinical signs and symptoms are often non-specific and require the medical provider to have a high degree of suspicion of these infections in order to be recognised. In this article, the causative agents, geographical distribution, clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment protocols are discussed for both babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Keywords Babesia, Ehrlichia, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, human, Borrelia Disclosure: Jyotsna Shah and Nick Harris are employees of IGeneX. Richard Horowitz is an employee of Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Eddie Caoili, and Sohini Stone, for providing technical assistance. -

Sequencing of the Smallest Apicomplexan Genome from The

Sequencing of the smallest apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia Microti Emmanuel Cornillot, Kamel Hadj-Kaddour, Amina Dassouli, Benjamin Noel, Vincent Ranwez, Benoit Vacherie, Yoann Augagneur, Virginie Brès, Aurelie Duclos, Sylvie Randazzo, et al. To cite this version: Emmanuel Cornillot, Kamel Hadj-Kaddour, Amina Dassouli, Benjamin Noel, Vincent Ranwez, et al.. Sequencing of the smallest apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia Microti. Nucleic Acids Research, Oxford University Press, 2012, 40 (18), pp.9102-9114. 10.1093/nar/gks700. lirmm-00818833 HAL Id: lirmm-00818833 https://hal-lirmm.ccsd.cnrs.fr/lirmm-00818833 Submitted on 29 Apr 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 9102–9114 Nucleic Acids Research, 2012, Vol. 40, No. 18 Published online 24 July 2012 doi:10.1093/nar/gks700 Sequencing of the smallest Apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia microtiy Emmanuel Cornillot1,*, Kamel Hadj-Kaddour1, Amina Dassouli1, Benjamin Noel2, Vincent Ranwez3, Benoıˆt Vacherie2, Yoann Augagneur4, Virginie Bre` s1, Aurelie Duclos2, Sylvie Randazzo1, Bernard Carcy1, Franc¸oise Debierre-Grockiego5, Ste´ phane Delbecq1, Karina Moubri-Me´ nage1, Hosam Shams-Eldin6, Sahar Usmani-Brown4, Fre´ de´ ric Bringaud7, Patrick Wincker2, Christian P. -

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - in This Issue

Volume 35, No. 5 August 2015 Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - In this issue... Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis— Connecticut, 2011-2014 17 Connecticut, 2011-2014 Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), Babesiosis Surveillance—Connecticut, 2014 19 formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, is a tick-borne disease caused by the bacterium contained information that was insufficient for case Anaplasma phagocytophilum. In Connecticut, HGA classification (e.g. positive laboratory test only, lost is transmitted to humans through the bite of an to follow-up). Of the 2,146 positive IgG titers only, infected Ixodes scapularis (deer tick or black-legged 7 (0.3%) were classified as a confirmed case after tick), the same tick that transmits Lyme disease and follow-up. During the same period, of the 483 babesiosis (1). positive PCR results received, 231 (48%) were The Connecticut Department of Public Health classified as a confirmed case after follow-up. (DPH) used the anaplasmosis National Surveillance Of the confirmed cases, date of onset of illness Case Definition (NSDC), which was established in was reported for 190 patients; 158 (84%) occurred 2009, to determine case status. The NSCD defines a during April - July. The ages of patients ranged confirmed case as a patient with clinically from 1-92 years (mean = 57.4). The age specific compatible illness characterized by acute onset of rates for confirmed cases was highest among those fever, plus one or more of the following: headache, 70-79 years of age (6.3 cases per 100,000 myalgia, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or population), and lowest for children < 9 years (0.3 elevated hepatic transaminases; plus 1) a fourfold cases per 100,000 population). -

Analyzing the Potential Transmission of Tick-Borne Pathogens to Man

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical ARTIGO 32(6):613-619, nov-dez, 1999. Report on ticks collected in the Southeast and Mid-West regions of Brazil: analyzing the potential transmission of tick-borne pathogens to man Relato sobre carrapatos coletados no Sudoeste e no Centro-oeste do Brasil analisando a potencial transmissão de microorganismos de carrapatos para o homem Luiz Tadeu Moraes Figueiredo1, Soraya Jabur Badra1, Luiz Eloy Pereira2 and Matias Pablo Juan Szabó3 Abstract Specimens of ticks were collected in 1993, 1996, 1997, and 1998, mostly from wild and domestic animals in the Southeast and Mid-West regions of Brazil. Nine species of Amblyommidae were identified: Anocentor nitens, Amblyomma cajennense, Amblyomma ovale, Amblyomma fulvum, Amblyomma striatum, Amblyomma rotundatum, Boophilus microplus, Boophilus annulatus, and Rhipicephalus sanguineus. The potential of these tick species as transmitters of pathogens to man was analyzed. A Flaviviridade Flavivirus was isolated from Amblyomma cajennense specimens collected from a sick capybara (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris). Amblyomma cajennense is the main transmitter of Rickettsia rickettsii (=R. rickettsi), the causative agent of spotted fever in Brazil. Wild mammals, mainly capybaras and deer, infested by ticks and living in close contact with cattle, horses and dogs, offer the risk of transmission of wild zoonosis to these domestic animals and to man. Key-words: Brazilian ticks. Tick-borne pathogens. Resumo Foram coletados espécimes de carrapatos em 1993, 1996, 1997, e 1998, principalmente de animais selvagens e domésticos, nas Regiões Sudeste e Centro-oeste do Brasil. Nove espécies de Amblyommidae foram identificadas: Anocentor Nitens, Amblyomma cajennense, Amblyomma ovale, Amblyomma fulvum, Amblyomma striatum, Amblyomma rotundatum, Boophilus microplus, Boophilus annulatus e Rhipicephalus sanguineus. -

A New Piroplasmid Species Infecting Dogs: Morphological and Molecular Characterization and Pathogeny of Babesia Negevi N

Baneth et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:130 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-3995-5 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access A new piroplasmid species infecting dogs: morphological and molecular characterization and pathogeny of Babesia negevi n. sp. Gad Baneth1* , Yaarit Nachum‑Biala1, Adam Joseph Birkenheuer2, Megan Elizabeth Schreeg2, Hagar Prince1, Monica Florin‑Christensen3, Leonhard Schnittger3,4 and Itamar Aroch1 Abstract Introduction: Babesiosis is a protozoan tick‑borne infection associated with anemia and life‑threatening disease in humans, domestic and wildlife animals. Dogs are infected by at least six well‑characterized Babesia spp. that cause clinical disease. Infection with a piroplasmid species was detected by light microscopy of stained blood smears from fve sick dogs from Israel and prompted an investigation on the parasite’s identity. Methods: Genetic characterization of the piroplasmid was performed by PCR amplifcation of the 18S rRNA and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) genes, DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Four of the dogs were co‑infected with Borrelia persica (Dschunkowsky, 1913), a relapsing fever spirochete transmitted by the argasid tick Ornithodoros tholozani Laboulbène & Mégnin. Co‑infection of dogs with B. persica raised the possibility of transmission by O. tholozani and therefore, a piroplasmid PCR survey of ticks from this species was performed. Results: The infected dogs presented with fever (4/5), anemia, thrombocytopenia (4/5) and icterus (3/5). Comparison of the 18S rRNA and cox1 piroplasmid gene sequences revealed 99–100% identity between sequences amplifed from diferent dogs and ticks. Phylogenetic trees demonstrated a previously undescribed species of Babesia belonging to the western group of Babesia (sensu lato) and closely related to the human pathogen Babesia duncani Conrad, Kjemtrup, Carreno, Thomford, Wainwright, Eberhard, Quick, Telfrom & Herwalt, 2006 while more moderately related to Babesia conradae Kjemtrup, Wainwright, Miller, Penzhorn & Carreno, 2006 which infects dogs.