Process Scheduling Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demystifying the Real-Time Linux Scheduling Latency

Demystifying the Real-Time Linux Scheduling Latency Daniel Bristot de Oliveira Red Hat, Italy [email protected] Daniel Casini Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Italy [email protected] Rômulo Silva de Oliveira Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil [email protected] Tommaso Cucinotta Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Italy [email protected] Abstract Linux has become a viable operating system for many real-time workloads. However, the black-box approach adopted by cyclictest, the tool used to evaluate the main real-time metric of the kernel, the scheduling latency, along with the absence of a theoretically-sound description of the in-kernel behavior, sheds some doubts about Linux meriting the real-time adjective. Aiming at clarifying the PREEMPT_RT Linux scheduling latency, this paper leverages the Thread Synchronization Model of Linux to derive a set of properties and rules defining the Linux kernel behavior from a scheduling perspective. These rules are then leveraged to derive a sound bound to the scheduling latency, considering all the sources of delays occurring in all possible sequences of synchronization events in the kernel. This paper also presents a tracing method, efficient in time and memory overheads, to observe the kernel events needed to define the variables used in the analysis. This results in an easy-to-use tool for deriving reliable scheduling latency bounds that can be used in practice. Finally, an experimental analysis compares the cyclictest and the proposed tool, showing that the proposed method can find sound bounds faster with acceptable overheads. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Computer systems organization → Real-time operating systems Keywords and phrases Real-time operating systems, Linux kernel, PREEMPT_RT, Scheduling latency Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.ECRTS.2020.9 Supplementary Material ECRTS 2020 Artifact Evaluation approved artifact available at https://doi.org/10.4230/DARTS.6.1.3. -

Interrupt Handling in Linux

Department Informatik Technical Reports / ISSN 2191-5008 Valentin Rothberg Interrupt Handling in Linux Technical Report CS-2015-07 November 2015 Please cite as: Valentin Rothberg, “Interrupt Handling in Linux,” Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat¨ Erlangen-Nurnberg,¨ Dept. of Computer Science, Technical Reports, CS-2015-07, November 2015. Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat¨ Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Department Informatik Martensstr. 3 · 91058 Erlangen · Germany www.cs.fau.de Interrupt Handling in Linux Valentin Rothberg Distributed Systems and Operating Systems Dept. of Computer Science, University of Erlangen, Germany [email protected] November 8, 2015 An interrupt is an event that alters the sequence of instructions executed by a processor and requires immediate attention. When the processor receives an interrupt signal, it may temporarily switch control to an inter- rupt service routine (ISR) and the suspended process (i.e., the previously running program) will be resumed as soon as the interrupt is being served. The generic term interrupt is oftentimes used synonymously for two terms, interrupts and exceptions [2]. An exception is a synchronous event that occurs when the processor detects an error condition while executing an instruction. Such an error condition may be a devision by zero, a page fault, a protection violation, etc. An interrupt, on the other hand, is an asynchronous event that occurs at random times during execution of a pro- gram in response to a signal from hardware. A proper and timely handling of interrupts is critical to the performance, but also to the security of a computer system. In general, interrupts can be emitted by hardware as well as by software. Software interrupts (e.g., via the INT n instruction of the x86 instruction set architecture (ISA) [5]) are means to change the execution context of a program to a more privileged interrupt context in order to enter the kernel and, in contrast to hardware interrupts, occur synchronously to the currently running program. -

Microkernel Mechanisms for Improving the Trustworthiness of Commodity Hardware

Microkernel Mechanisms for Improving the Trustworthiness of Commodity Hardware Yanyan Shen Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Computer Science and Engineering Faculty of Engineering March 2019 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Shen Given Name/s : Yanyan Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar : PhD Faculty : Faculty of Engineering School : School of Computer Science and Engineering Microkernel Mechanisms for Improving the Trustworthiness of Commodity Thesis Title : Hardware Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The thesis presents microkernel-based software-implemented mechanisms for improving the trustworthiness of computer systems based on commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) hardware that can malfunction when the hardware is impacted by transient hardware faults. The hardware anomalies, if undetected, can cause data corruptions, system crashes, and security vulnerabilities, significantly undermining system dependability. Specifically, we adopt the single event upset (SEU) fault model and address transient CPU or memory faults. We take advantage of the functional correctness and isolation guarantee provided by the formally verified seL4 microkernel and hardware redundancy provided by multicore processors, design the redundant co-execution (RCoE) architecture that replicates a whole software system (including the microkernel) onto different CPU cores, and implement two variants, loosely-coupled redundant co-execution (LC-RCoE) and closely-coupled redundant co-execution (CC-RCoE), for the ARM and x86 architectures. RCoE treats each replica of the software system as a state machine and ensures that the replicas start from the same initial state, observe consistent inputs, perform equivalent state transitions, and thus produce consistent outputs during error-free executions. -

Lecture 11: Deadlock, Scheduling, & Synchronization October 3, 2019 Instructor: David E

CS 162: Operating Systems and System Programming Lecture 11: Deadlock, Scheduling, & Synchronization October 3, 2019 Instructor: David E. Culler & Sam Kumar https://cs162.eecs.berkeley.edu Read: A&D 6.5 Project 1 Code due TOMORROW! Midterm Exam next week Thursday Outline for Today • (Quickly) Recap and Finish Scheduling • Deadlock • Language Support for Concurrency 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.2 Recall: CPU & I/O Bursts • Programs alternate between bursts of CPU, I/O activity • Scheduler: Which thread (CPU burst) to run next? • Interactive programs vs Compute Bound vs Streaming 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.3 Recall: Evaluating Schedulers • Response Time (ideally low) – What user sees: from keypress to character on screen – Or completion time for non-interactive • Throughput (ideally high) – Total operations (jobs) per second – Overhead (e.g. context switching), artificial blocks • Fairness – Fraction of resources provided to each – May conflict with best avg. throughput, resp. time 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.4 Recall: What if we knew the future? • Key Idea: remove convoy effect –Short jobs always stay ahead of long ones • Non-preemptive: Shortest Job First – Like FCFS where we always chose the best possible ordering • Preemptive Version: Shortest Remaining Time First – A newly ready process (e.g., just finished an I/O operation) with shorter time replaces the current one 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.5 Recall: Multi-Level Feedback Scheduling Long-Running Compute Tasks Demoted to Low Priority • Intuition: Priority Level proportional -

Advanced Operating Systems #1

<Slides download> https://www.pf.is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/classes Advanced Operating Systems #2 Hiroyuki Chishiro Project Lecturer Department of Computer Science Graduate School of Information Science and Technology The University of Tokyo Room 007 Introduction of Myself • Name: Hiroyuki Chishiro • Project Lecturer at Kato Laboratory in December 2017 - Present. • Short Bibliography • Ph.D. at Keio University on March 2012 (Yamasaki Laboratory: Same as Prof. Kato). • JSPS Research Fellow (PD) in April 2012 – March 2014. • Research Associate at Keio University in April 2014 – March 2016. • Assistant Professor at Advanced Institute of Industrial Technology in April 2016 – November 2017. • Research Interests • Real-Time Systems • Operating Systems • Middleware • Trading Systems Course Plan • Multi-core Resource Management • Many-core Resource Management • GPU Resource Management • Virtual Machines • Distributed File Systems • High-performance Networking • Memory Management • Network on a Chip • Embedded Real-time OS • Device Drivers • Linux Kernel Schedule 1. 2018.9.28 Introduction + Linux Kernel (Kato) 2. 2018.10.5 Linux Kernel (Chishiro) 3. 2018.10.12 Linux Kernel (Kato) 4. 2018.10.19 Linux Kernel (Kato) 5. 2018.10.26 Linux Kernel (Kato) 6. 2018.11.2 Advanced Research (Chishiro) 7. 2018.11.9 Advanced Research (Chishiro) 8. 2018.11.16 (No Class) 9. 2018.11.23 (Holiday) 10. 2018.11.30 Advanced Research (Kato) 11. 2018.12.7 Advanced Research (Kato) 12. 2018.12.14 Advanced Research (Chishiro) 13. 2018.12.21 Linux Kernel 14. 2019.1.11 Linux Kernel 15. 2019.1.18 (No Class) 16. 2019.1.25 (No Class) Linux Kernel Introducing Synchronization /* The cases for Linux */ Acknowledgement: Prof. -

What Is an Operating System III 2.1 Compnents II an Operating System

Page 1 of 6 What is an Operating System III 2.1 Compnents II An operating system (OS) is software that manages computer hardware and software resources and provides common services for computer programs. The operating system is an essential component of the system software in a computer system. Application programs usually require an operating system to function. Memory management Among other things, a multiprogramming operating system kernel must be responsible for managing all system memory which is currently in use by programs. This ensures that a program does not interfere with memory already in use by another program. Since programs time share, each program must have independent access to memory. Cooperative memory management, used by many early operating systems, assumes that all programs make voluntary use of the kernel's memory manager, and do not exceed their allocated memory. This system of memory management is almost never seen any more, since programs often contain bugs which can cause them to exceed their allocated memory. If a program fails, it may cause memory used by one or more other programs to be affected or overwritten. Malicious programs or viruses may purposefully alter another program's memory, or may affect the operation of the operating system itself. With cooperative memory management, it takes only one misbehaved program to crash the system. Memory protection enables the kernel to limit a process' access to the computer's memory. Various methods of memory protection exist, including memory segmentation and paging. All methods require some level of hardware support (such as the 80286 MMU), which doesn't exist in all computers. -

Embedded Systems

Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering STUDY MATERIAL for III rd Year VI th Semester Subject Name: EMBEDDED SYSTEMS Prepared by Dr.P.Venkatesan, Associate Professor, ECE, SCSVMV University Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering PRE-REQUISITE: Basic knowledge of Microprocessors, Microcontrollers & Digital System Design OBJECTIVES: The student should be made to – Learn the architecture and programming of ARM processor. Be familiar with the embedded computing platform design and analysis. Be exposed to the basic concepts and overview of real time Operating system. Learn the system design techniques and networks for embedded systems to industrial applications. Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering SYLLABUS UNIT – I INTRODUCTION TO EMBEDDED COMPUTING AND ARM PROCESSORS Complex systems and micro processors– Embedded system design process –Design example: Model train controller- Instruction sets preliminaries - ARM Processor – CPU: programming input and output- supervisor mode, exceptions and traps – Co- processors- Memory system mechanisms – CPU performance- CPU power consumption. UNIT – II EMBEDDED COMPUTING PLATFORM DESIGN The CPU Bus-Memory devices and systems–Designing with computing platforms – consumer electronics architecture – platform-level performance analysis - Components for embedded programs- Models of programs- -

Advanced Scheduling

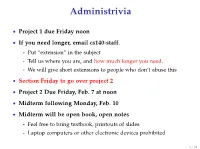

Administrivia • Project 1 due Friday noon • If you need longer, email cs140-staff. - Put “extension” in the subject - Tell us where you are, and how much longer you need. - We will give short extensions to people who don’t abuse this • Section Friday to go over project 2 • Project 2 Due Friday, Feb. 7 at noon • Midterm following Monday, Feb. 10 • Midterm will be open book, open notes - Feel free to bring textbook, printouts of slides - Laptop computers or other electronic devices prohibited 1 / 38 Fair Queuing (FQ) [Demers] • Digression: packet scheduling problem - Which network packet should router send next over a link? - Problem inspired some algorithms we will see today - Plus good to reinforce concepts in a different domain. • For ideal fairness, would use bit-by-bit round-robin (BR) - Or send more bits from more important flows (flow importance can be expressed by assigning numeric weights) Flow 1 Flow 2 Round-robin service Flow 3 Flow 4 2 / 38 SJF • Recall limitations of SJF from last lecture: - Can’t see the future . solved by packet length - Optimizes response time, not turnaround time . but these are the same when sending whole packets - Not fair Packet scheduling • Differences from CPU scheduling - No preemption or yielding—must send whole packets . Thus, can’t send one bit at a time - But know how many bits are in each packet . Can see the future and know how long packet needs link • What scheduling algorithm does this suggest? 3 / 38 Packet scheduling • Differences from CPU scheduling - No preemption or yielding—must send whole packets . -

Linux Kernal II 9.1 Architecture

Page 1 of 7 Linux Kernal II 9.1 Architecture: The Linux kernel is a Unix-like operating system kernel used by a variety of operating systems based on it, which are usually in the form of Linux distributions. The Linux kernel is a prominent example of free and open source software. Programming language The Linux kernel is written in the version of the C programming language supported by GCC (which has introduced a number of extensions and changes to standard C), together with a number of short sections of code written in the assembly language (in GCC's "AT&T-style" syntax) of the target architecture. Because of the extensions to C it supports, GCC was for a long time the only compiler capable of correctly building the Linux kernel. Compiler compatibility GCC is the default compiler for the Linux kernel source. In 2004, Intel claimed to have modified the kernel so that its C compiler also was capable of compiling it. There was another such reported success in 2009 with a modified 2.6.22 version of the kernel. Since 2010, effort has been underway to build the Linux kernel with Clang, an alternative compiler for the C language; as of 12 April 2014, the official kernel could almost be compiled by Clang. The project dedicated to this effort is named LLVMLinxu after the LLVM compiler infrastructure upon which Clang is built. LLVMLinux does not aim to fork either the Linux kernel or the LLVM, therefore it is a meta-project composed of patches that are eventually submitted to the upstream projects. -

A Linux Kernel Scheduler Extension for Multi-Core Systems

A Linux Kernel Scheduler Extension For Multi-Core Systems Aleix Roca Nonell Master in Innovation and Research in Informatics (MIRI) specialized in High Performance Computing (HPC) Facultat d’informàtica de Barcelona (FIB) Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Supervisor: Vicenç Beltran Querol Cosupervisor: Eduard Ayguadé Parra Presentation date: 25 October 2017 Abstract The Linux Kernel OS is a black box from the user-space point of view. In most cases, this is not a problem. However, for parallel high performance computing applications it can be a limitation. Such applications usually execute on top of a runtime system, itself executing on top of a general purpose kernel. Current runtime systems take care of getting the most of each system core by distributing work among the multiple CPUs of a machine but they are not aware of when one of their threads perform blocking calls (e.g. I/O operations). When such a blocking call happens, the processing core is stalled, leading to performance loss. In this thesis, it is presented the proof-of-concept of a Linux kernel extension denoted User Monitored Threads (UMT). The extension allows a user-space application to be notified of the blocking and unblocking of its threads, making it possible for a core to execute another worker thread while the other is blocked. An existing runtime system (namely Nanos6) is adapted, so that it takes advantage of the kernel extension. The whole prototype is tested on a synthetic benchmarks and an industry mock-up application. The analysis of the results shows, on the tested hardware and the appropriate conditions, a significant speedup improvement. -

Efficient Interrupts on Cortex-M Microcontrollers

Efficient Interrupts on Cortex-M Microcontrollers Chris Shore Training Manager ARM Ltd Cambridge, UK [email protected] Abstract—The design of real-time embedded systems involves So, assuming that we have a system which is powerful a constant trade-off between meeting real-time design goals and enough to meet all its real-time design constraints, we have a operating within power and energy budgets. This paper explores secondary problem. how the architectural features of ARM® Cortex®-M microcontrollers can be used to maximize power efficiency while That problem is making the system as efficient as possible. ensuring that real-time goals are met. If we have sufficient processing power, it is relatively trivial to conceive and implement a design which meets all time-related Keywords—interrupts; microcontroller; real-time; power goals but such a system might be extremely inefficient when it efficiency. comes to energy consumption. The requirement to minimize energy consumption introduces another set of goals and I. INTRODUCTION constraints. It requires us to make use of sleep modes and low A “real-time” system is one which has to react to external power modes in the hardware, to use the most efficient events within certain time constraints. Wikipedia says: methods for switching from one event to another and to maximize “idle time” in the design to make opportunities to “A system is real-time if the total correctness on an use low power modes. operation depends not only on its logical correctness but also upon the time in which it is performed.” The battle is between meeting the time constraints while using the least amount of energy in doing so. -

Chapter 5. Kernel Synchronization

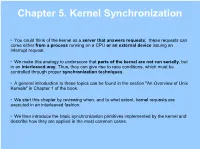

Chapter 5. Kernel Synchronization You could think of the kernel as a server that answers requests; these requests can come either from a process running on a CPU or an external device issuing an interrupt request. We make this analogy to underscore that parts of the kernel are not run serially, but in an interleaved way. Thus, they can give rise to race conditions, which must be controlled through proper synchronization techniques. A general introduction to these topics can be found in the section "An Overview of Unix Kernels" in Chapter 1 of the book. We start this chapter by reviewing when, and to what extent, kernel requests are executed in an interleaved fashion. We then introduce the basic synchronization primitives implemented by the kernel and describe how they are applied in the most common cases. 5.1.1. Kernel Preemption a kernel is preemptive if a process switch may occur while the replaced process is executing a kernel function, that is, while it runs in Kernel Mode. Unfortunately, in Linux (as well as in any other real operating system) things are much more complicated: Both in preemptive and nonpreemptive kernels, a process running in Kernel Mode can voluntarily relinquish the CPU, for instance because it has to sleep waiting for some resource. We will call this kind of process switch a planned process switch. However, a preemptive kernel differs from a nonpreemptive kernel on the way a process running in Kernel Mode reacts to asynchronous events that could induce a process switch - for instance, an interrupt handler that awakes a higher priority process.