Overcoming the Threat of Low Cost Carriers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Regional Airlines in Eastern Europe Have the Right to Survive in the European Single Sky Environment?

AVIATION ISSN 1648-7788 / eISSN 1822-4180 2017 Volume 21(4): 155–161 doi:10.3846/16487788.2017.1415226 DO REGIONAL AIRLINES IN EASTERN EUROPE HAVE THE RIGHT TO SURVIVE IN THE EUROPEAN SINGLE SKY ENVIRONMENT? Sven KUKEMELK1, 2 1Nordic Aviation Group, Sepise 1, Tallinn, 11415, Estonia 2Tallinn University of Technology, Department of Economics and Business Administration, Akadeemia tee 3, Tallinn, 12618, Estonia E-mail: [email protected] Received 15 June 2017; accepted 06 December 2017 Sven KUKEMELK Education: Estonian Aviation Academy (2010), Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (2012), Tallinn University of Technology, PhD studies (since 2013). Experience: 7 years of experience in network planning and aviation business analysis. Research interests: network planning, fleet development, commercial management. Present position: CEO of Nordic Aviation Advisory, Executive Director for Business Development at Nordic Aviation Group. Abstract. The European aviation market can be characterised by extreme growth and turbulence ever since the markets were deregulated and low cost carriers emerged on the continent. Initially the biggest toll was paid by main legacy carriers when low costs emerged on trunk routes, which lead to the bankruptcy of Sabena, Swiss airlines and Spanair. However, once big legacy carriers started merging and creating more alliances, sustainability was once again reached. Despite this, as low cost carriers entered the Eastern-European market and looked to stimulate even smaller regional routes, smaller carriers started to suffer. This article is assessing the status quo of the current European region- al aviation, highlighting the recent trends and ultimately coming to a conclusion that regional airlines can be sustaina- ble provided that certain key criteria have been met. -

New Air Travel Opportunities for Ceuta, a Spanish Remoter Region in Northern Africa, Generated by Air Transport Liberalisation in Neighbouring Morocco

Disciplines Andreas Papathedorou | University of West London, UK Ioulia Poulaki | University of West London, UK OPEN SKIES New air travel opportunities for Ceuta, a Spanish remoter region in Northern Africa, generated by air transport liberalisation in neighbouring Morocco. Spatial discontinuity and lack of seamless transport connections between Ceuta and the Spanish mainland pose significant accessibility challenges for the Spanish exclave 16 New Vistas • Volume 2 Issue 1 • www.uwl.ac.uk • © University of West London Article Open Skies | Author Andreas Papathedorou and Ioulia Poulaki An integrated intermodal transport system, with seamless connections of different public transport modes, may positively affect an airport enhancement of its catchment area ransport in remote regions of the world Remoter regions around the world are usually denied sufficient T surface transport services to metropolitan centres. This may be the result of a fragmented pattern in physical geography (e.g. islands separated from the mainland by sea), which renders surface transport impossible; and/ or the outcome of socio-political geography friction (e.g. disputed areas close to the frontier of neighbouring countries) which makes investment in expensive surface transport infrastructure very unappealing. For these reasons, remoter regions and their local societies depend heavily on air transport to ensure accessibility and economic and cultural connectivity to the wider world. Local airports provide the necessary means for airlines to operate their services; in certain cases, however, such airports may be located in a neighbouring country thus raising the levels of complexity in the transport system. Studying, therefore, the range of an airport’s catchment area becomes of great significance. -

Liste-Exploitants-Aeronefs.Pdf

EN EN EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, XXX C(2009) XXX final COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) EN EN COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC1, and in particular Article 18a(3)(a) thereof, Whereas: (1) Directive 2003/87/EC, as amended by Directive 2008/101/EC2, includes aviation activities within the scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community (hereinafter the "Community scheme"). (2) In order to reduce the administrative burden on aircraft operators, Directive 2003/87/EC provides for one Member State to be responsible for each aircraft operator. Article 18a(1) and (2) of Directive 2003/87/EC contains the provisions governing the assignment of each aircraft operator to its administering Member State. The list of aircraft operators and their administering Member States (hereinafter "the list") should ensure that each operator knows which Member State it will be regulated by and that Member States are clear on which operators they should regulate. -

EQUINIX INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS EXCHANGE™ (IBX®) and Xscale™ DATA CENTER QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE

EQUINIX INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS EXCHANGE™ (IBX®) AND xSCALE™ DATA CENTER QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Updated July 2021 NORTH AMERICA IBX ADDRESS LOCATION OWNERSHIP COLO SQ M COLO SQ FT BUILDING TYPE AT1 Atlanta 180 Peachtree Street NW • 11 mi (18 km) from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Leased 7,469 80,397 6-story, reinforced steel and concrete with 2nd, 3rd and 6th Floors Airport (ATL) brick face Atlanta, GA 30303 AT2 Atlanta 56 Marietta Street NW • 11 mi (18 km) from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Leased 602 6,475 10-story, concrete steel structure, glass 5th Floor Airport (ATL) face Atlanta, GA 30303 AT3 Atlanta 56 Marietta Street NW • 11 mi (18 km) from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Leased 872 9,390 10-story, concrete steel structure, glass 6th Floor Airport (ATL) face Atlanta, GA 30303 AT4 Atlanta 450 Interstate North Parkway • 21 mi (34 km) from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Owned 6,204 66,774 2-story, steel-framed building with Atlanta, GA 30339 Airport (ATL) concrete block over steel frame AT5 Atlanta 2836 Peterson Place NW • 28 mi (45 km) from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Leased 1,982 21,337 1-story, steel-framed building with Norcross, GA 30071 Airport (ATL) concrete block and brick veneer BO2 Boston 41 Alexander Road • 21 mi (33 km) from Logan Intl Airport (BOS) Owned 7,036 75,734 1-story, tilt-up concrete panels over steel Billerica, MA 01821 CH1 Chicago 350 East Cermak Road • 10 mi (17 km) from Midway Intl Airport (MDW) Leased 4,737 50,992 9-story (main section), two-way flat slab 5th Floor concrete construction (existing -

Economic Instruments for Reducing Aircraft Noise Theoretical Framework

European LCCs going hybrid: An empirical survey Roland Conrady, Frank Fichert and Richard Klophaus Worms University of Applied Sciences, Germany Competence Center Aviation Management (CCAM) Airneth Annual Conference The Hague, April 14, 2011 Agenda • Motivation/Background • Textbook definition of pure/archetypical LCC • Data for empirical survey • Empirical results: Classification of airline’s business models • Conclusions/discussion Roland Conrady, Frank Fichert, Richard Klophaus – European LCCs going hybrid – The Hague, April 14, 2011 2 Motivation / Background • Significant (and still growing) market share of LCCs in Europe. • Obviously different strategies within the LCC segment. • Market observers see trends towards “hybridization” and/or “converging business models”,e.g.: “On many fronts - pricing, product offering, distribution, fleet, network design and even cost structure - the previously obvious and often blatant differences between budget and legacy carriers are now no longer so apparent. This has resulted from the movement of both parties in the same direction, toward the mainstream middle.” Airline Business, May 2009 (emphasis added). Roland Conrady, Frank Fichert, Richard Klophaus – European LCCs going hybrid - The Hague, April 14, 2011 3 Motivation / Background • Dynamic market environment with recent changes, e.g. some LCCs offering transfer flights or can be booked via GDS. • Yet, very limited empirical analysis of “hybridization”. Roland Conrady, Frank Fichert, Richard Klophaus – European LCCs going hybrid - The Hague, April 14, 2011 4 Aim of the paper It is examined • to what extent carriers today blend low-cost characteristics with the business characteristics of traditional full-service airlines, and • which characteristics remain distinct between LCCs and traditional full-service airlines and which tend to be common for all carriers. -

Time Departure FLIGHTS from SABİHA GÖKÇEN AIRPORT

Wings of Change Europe Master of Ceremony Montserrat Barriga Director General European Regions Airline Association (ERA) Wings of Change Europe – 13/14 November 2018 – Madrid , Spain Wifi Hilton Honors Password APMAD08 Wings of Change Europe – 13/14 November 2018 – Madrid , Spain Welcome remarks Luis Gallego CEO Iberia Wings of Change Europe – 13/14 November 2018 – Madrid , Spain Welcome to Madrid Iberia in figures Flying since Member of Three Business: Airline Maintenance 1927 3 Handing Employees Incomes 2017 €376 Operating profits 2017 17.500 €4.85 Billion (+39% vs 2016) What does Iberia bring to Madrid? 17,500 109 23,000,000 142 employees International aircraft destinations passengers 50% 5,5% 50,000 GDP Indirect Madrid Airport employees Our strategic roadmap The 2013 2014 2017 2012 future Transformation Plan de Futuro Plan de Futuro Struggling Transforming Plan Phase 2 for survival to reach excellence On the verge of Loses cut by half Back to profitability The most punctual airline bankruptcy in the world Four star Skytrax Highest operational profits in Iberia’s 90 years of history 2018 had significant challenges for IB. How are we doing? Financial People Results Customer Muchas gracias The Value of Aviation & importance of Competitiveness for Spain Jose Luis Ábalos Minister of Public Works Government of Spain Wings of Change Europe – 13/14 November 2018 – Madrid , Spain The European Commission’s perspective on the future of aviation in the EU and its neighboring countries Henrik Hololei Director General for Mobility & Transport European -

22Nd Biennial Symposium of the IMSSS

22nd Biennial Symposium of the IMSSS CONVERSIONS AND LIFE PASSAGES THROUGH THE MIRROR OF MEDIEVAL PREACHERS The Dominican Casa de Espiritualidad y Ejercicios León, Spain / July 17-21, 2020 PRACTICAL INFORMATION LOCATION: The venue is located less than 2 km from León's airport. People flying in from outside of Spain should fly to Barcelona from where they can change to a direct flight from Barcelona to León. The street address of the Casa de Espiritualidad: Avda. de Astorga, 87 24198 La Virgen del Camino (LEÓN) Tel: (0034) 679 332 768 // 987 300 987 e-mail: [email protected] GETTING THERE: By airplane: León Airport: There are direct flights with Iberia Airlines from Barcelona (schedule not confirmed). Asturias Airport (Oviedo): 170km, about 2 hours from León. We are going to set up a bus transfer from the Airport of Asturias to the Casa de Espiritualidad y Ejercicios on the 17th of July around 12:00 and to the Airport on the 21st around 15:00. Madrid Adolfo Suárez Airport: 350 km. You will need to transfer from the Airport to the Chamartín Train Station by taking a regional train or a combination of the Metro and a regional train, both of which are located inside the airport terminals. Since the Madrid Airport has 4 terminals, we recommend that you consult the Google Maps instructions to find the best route: https://www.google.es/maps/dir/Madrid- Barajas+Adolfo+Su%C3%A1rez+Airport,+Av+de+la+Hispanidad,+s%2Fn,+28042+Madrid/Estacion+de+ Chamartin,+28036+Madrid/@40.4722831,- 3.7002189,12z/data=!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0xd4231d000000001:0x6e7725ea0f85ceef!2m2!1d- 3.5675982!2d40.4983322!1m5!1m1!1s0xd42293e290b606d:0x371c6af06d627cea!2m2!1d- 3.6825565!2d40.4718908!3e3?hl=en&authuser=0 By train: Renfe’s AVE (fast train) from Madrid (Chamartín Train Station): Several trains per day. -

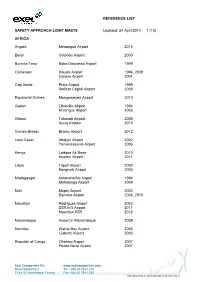

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

Make Business Trips Easier with These 4 Travel Hacks

MAY 2016 NEWSLETTER American and United Will Soon Offer PAGE 3 No-Frills Fares Southwest Raises EarlyBird Check-In PAGE 4 Make Business Trips Easier With These 4 Travel Hacks 1 INFocusPAGEPAGE Newsletter 22 Make Business Trips Easier With These 4 Travel Hacks By Brit Tulloch Travelling frequently for work can be 2. Stress less with a travel stick the bag to the back of the seat in draining, on you and your wallet. But it checklist front of you. You can watch what you want doesn’t have to be that way. without straining your neck. It may seem obsessive, but creating There are a few travel tips you can use a travel checklist before you jet off will 4. Save time with the rolling to save money on business trips, making do wonders for your stress levels. You technique your travel experience a little more no longer have to worry about packing pleasant. enough socks or a spare laptop charger. Ever wondered how soldiers fit all their provisions into one backpack? They have 1. Feel more at home with a Use this free app to organise your a special technique for rolling and folding serviced apartment packing, scheduling and other details. their clothes, to allow for maximum space. Staying in hotels every time you travel 3. Create your own inflight With this technique, you can save time can be a downer. The sterile surrounds entertainment at the baggage carousel by travelling with lack the warmth and character of home. only one suitcase. Instead, find the next best thing by staying Smartphones and iPads offer better in a serviced apartment. -

Advanced Seat Reservation

Advanced Seat Reservation Iberia, Iberia Express and Iberia Regional Air Nostrum extend to all fares the possibility of advanced seat reservation from the moment of ticket purchase • The advanced seat reservation is only applicable on flights operated by Iberia, Iberia Express and Iberia Regional Air Nostrum , is only applicable to individual passengers with previously issued flight tickets and, is subject to the availability of seats at the moment of request. • This service is free of charge for passengers travelling in Business class . • For passengers in Economy class this service is voluntary and subject to charges , except for those passengers on Economy Full Fare (Y), fares B, H, K, M, Z, L, A , Club Fiesta passengers, Iberia Plus Platinum and Gold card holders and their equivalents in oneworld Emerald and Sapphire, for whom it's free of charge . • Passengers can choose their seat in the Economy cabin before checking-in online or in person at the airport, provided they have previously issued tickets. • For security reasons, the use of emergency seats, including Economy XL , continue to be subject to certain requirements. • For check-in at the airport, or through on-line check-in unreserved seats are free for all passengers. Flights which can sell paid seats Only Iberia flights operated by Iberia, Iberia Expess and Air Nostrum Flights which do not sell paid seats • Code-share marketing other airlines - flights operated by Iberia - • Code-share IB4000-4999 // IB7000-7999 - flights operated by other airlines - If free assignation is allowed, the conditions applied will be determined by the operating airline. Code-share IB5000-5999 -flights operated by Vueling - There is no seat assignation • Air Shuttle flights • Charter flights TERMS AND CONDITIONS: Terms and Conditions of paid seats The prior reservation of paid seats is optional, is subject to the availability of seats at the moment of request and is only applicable on flights operated by Iberia and Iberia Regional Air Nostrum to individual passengers with previously issued flight tickets. -

Listado De Certificados De Operador Aéreo (AOC) De Avión Y Helicóptero

Listado de Certificados de Operador Aéreo (AOC) de avión y helicóptero. Fecha de generación: 27-09-2021 Operador DBA Número AOC Flotas ATR 72-200 SERIES AERONOVA, S.L. AIR EUROPA EXPRESS ES.AOC.020 BOEING 737-800 SERIES EMBRAER ERJ 190-200 LR AIRBUS A330-200 AIRBUS A330-300 (RR) AIR EUROPA LINEAS AEREAS, S.A. AIR EUROPA ES.AOC.004 BOEING 737-800 SERIES BOEING 787-8 BOEING 787-9 ATR 72-212 A AIR NOSTRUM LINEAS AEREAS DEL AIR NOSTRUM LINEAS AEREAS DEL BOMBARDIER CL-600-2B19 ES.AOC.002 MEDITERRANEO, S.A. MEDITERRANEO BOMBARDIER CL-600-2D24 BOMBARDIER CL-600-2E25 AIR TAXI & CHARTER AIR TAXI & CHARTER CESSNA 525 ES.AOC.088 INTERNATIONAL, S.L INTERNATIONAL CESSNA 525A BOEING 737-400 SERIES ALBASTAR, S.A. ALBASTAR ES.AOC.106 BOEING 737-800 SERIES ANA MARIA ALEGRE GALINDO PIRIVUELO ES.AOC.148 ROBIN DR 400/180 R AURA AIRLINES, S.L. GOWAIR Vacation Airlines ES.AOC.146 AIRBUS A320-200 BABCOCK MISSION CRITICAL BABCOCK MISSION CRITICAL ES.AOC.046 BEECHCRAFT B200 SERVICES ESPAÑA, S.A. SERVICES ESPAÑA AGUSTA 139 AGUSTA A109E AGUSTA A109S AGUSTA-BELL AB 412 BABCOCK MISSION CRITICAL BABCOCK MISSION CRITICAL ES.AOC.129 BELL 412 SERVICES ESPAÑA, S.A. SERVICES ESPAÑA BELL 412EP EUROCOPTER EC135 P2 EUROCOPTER EC135 T2 EUROCOPTER EC135 T2+ EUROCOPTER EC135 T3 EUROCOPTER MBB-BK 117 C-2 EUROCOPTER MBB-BK117 D-2 BARON 58, S.L.U. BARON 58, S.L.U. ES.AOC.132 EUROCOPTER AS355F2 AGUSTA A109A II AGUSTA-BELL AB 206 B BELL 206B BIGAS GRUP HELICOPTERS SL ES.AOC.136 EUROCOPTER AS 350 B EUROCOPTER EC 130B4 ROBINSON R44 ROBINSON R44 II ATR 72-212 A BINTER CANARIAS, S.A. -

Aena Magazine Rich.Indd 11 21/5/07 18:15:12 12 347332392383475498774709909029989935499

An official report for the aviation community. 3 Contents P.4 Javier Marin Director of Spanish airports Madrid Barajas A national asset P.8 José Manuel Hesse The ‘architect’ of Plan Barajas Award-winning P.27 Architectural design Maria Dolores Izquierdo P.33 P.11 Retail – every case is different Plan Barcelona The engine of Catalonia Innovation in IT P.38 P.17 First-rate, in-house expertise The Malaga plan A benchmark for tourist airports A three-way partnership P.20 Air navigation, airlines and airports The Levante Plan P.41 Alicante and Valencia Security P.24First, last and always Canarias plan P.47 The lucky airports P.51 4 Madrid Barajas Spain’s window on the world Airport Business asked Aena’s director of Spanish airports Javier Marin to spell out the significance of Plan Barajas, including the award-winning Madrid Barajas Terminal 4. John Frank-Keyes reports. “ 5 adrid Barajas is absolutely vital for air transport in Spain because of its hub function. However, we faced significant capacity limitations, so these infrastructure developments were crucial – and not just for Madrid, but for Spain and indeed for Europe. We now have the capacity to move up from being Europe’s fifth-ranked airport, and indeed it is something we have been able to achieve as we are now fourth in the first quarter of 2007,” Marin replied. Previously, Barajas had hourly runway capacity of 78 movements per hour with passenger mgrowth of about 8% a year. “The full benefits of the new capacity have really been felt with the advent of the winter season when we have been able to offer 90 movements per hour.