Notes to Self: the Visual Culture of Selfies in the Age of Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

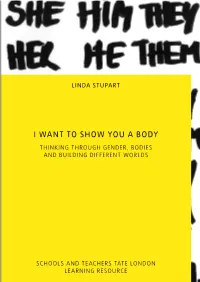

I Want to Show You a Body Thinking Through Gender, Bodies and Building Different Worlds

LINDA STUPART I WANT TO SHOW YOU A BODY THINKING THROUGH GENDER, BODIES AND BUILDING DIFFERENT WORLDS SCHOOLS AND TEACHERS TATE LONDON LEARNING RESOURCE INTRODUCTION Growing up as a gender non-conforming adults) we learn that 53% of respondents child, it was art and being in the art room had self-harmed at some point, of which that was my safe haven. Like other gender 31% had self-harmed weekly and 23% daily. and sexually diverse people, such as lesbian, These and other surveys show that many gay, bisexual and queer people, trans and trans people experience mental distress, gender-questioning people can be made and we know that there is a direct correlation to feel ashamed of who we are, and we between this and our experiences of have to become more resilient to prejudice discrimination and poor understandings in society. Art can help with this. There is of gender diversity. As trans people, we no right and wrong when it comes to art. need to be able to develop resilience and There’s space to experiment. to manage the setbacks that we might Art is where I found my politics; where experience. We need safe spaces to explore I became a feminist. Doing art and learning our feelings about our gender. about art was where I knew that there was Over recent years at Gendered Intelligence another world out there; a more liberal one; we have delivered a range of art-making more radical perhaps; it offered me hope projects for young trans and gender- of a world where I would belong. -

NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019 – 11 January 2020 Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce its first exhibition with Nan Goldin, who joined the gallery in September 2018. This major exhibition – the first solo presentation by the artist in London since the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002 – presents an important range of historical works together with three new video works exhibited for the first time. Over the past year Goldin has been working on a significant new digital slideshow titled Memory Lost (2019), recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction. This captivating, beautiful and haunting journey unfolds through an assemblage of intimate and personal imagery to offer a poignant reflection on memory and the darkness of addiction. It is one of the most moving, personal and visually arresting narratives of Goldin’s career to date, and is accompanied by an emotionally charged new score commissioned from composer and instrumentalist Mica Levi. Documenting a life at once familiar yet reframed, new archival imagery is cast to portray memory as lived and witnessed experience, yet altered and lost through the effects of drugs. Bearing thematic connections to Memory Lost, another new video work, Sirens (2019), is presented in the same space. This is the first work by Goldin exclusively made from found video footage and is also accompanied by a new score by Mica Levi. Echoing the enchanting call of the Sirens from Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores, this hypnotic work visually and acoustically entrances the viewer into the experience of being high. -

NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAN GOLDIN Sirens 14 November 2019 – 11 January 2020 Opening reception, Thursday 14 November, 6-8 pm Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to announce its first exhibition with Nan Goldin, who joined the gallery in September 2018. This major exhibition – the first solo presentation by the artist in London since the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002 – will present an important range of historical works together with three new video works exhibited for the first time. Over the past year Goldin has been working on a significant new digital slideshow titled Memory Lost (2019), recounting a life lived through a lens of drug addiction. This captivating, beautiful and haunting journey unfolds through an assemblage of intimate and personal imagery to offer a poignant reflection on memory and the darkness of addiction. It is one of the most moving, personal and visually arresting narratives of Goldin’s career to date, and is accompanied by an emotionally charged new score commissioned from composer and instrumentalist Mica Levi. Documenting a life at once familiar and reframed, new archival imagery is cast to portray memory as lived and witnessed experience, yet altered and lost through the effects of drugs. Bearing thematic connections to Memory Lost, another new video work, Sirens (2019), will be presented in the same space. This is the first work by Goldin exclusively made from found video footage and it will also be accompanied by a new score by Mica Levi. Echoing the enchanting call of the Sirens from Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores, this hypnotic work visually and acoustically entrances the viewer into the experience of being high. -

Nan Goldin: Unafraid of the Dark

Nan Goldin: unafraid of the dark The photographer Nan Goldin pulled no punches in her studies of the drag queens, junkies and prostitutes that made up her dysfunctional New York 'family’. By Drusilla Beyfus (June 26, 2009) Nan Goldin: Picnic on the Esplanade, 1973 ‘I’m just less absolute.’ It was a throwaway remark made by Nan Goldin as we discussed her forthcoming show at the 40th anniversary of the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival. But it could be taken as a lead on the way that Goldin thinks about herself and her work today. Anything less intense about her would lower the temperature like no tomorrow. Goldin is internationally recognised for a vast body of work, the core of which is a pictures-and- text diary of her personal experiences. She has a confessional approach to her affairs, and is indifferent to conventional limits. Many living photographers have been influenced by her, including Corinne Day, Wolfgang Tillmans and Juergen Teller. In France she will show her totem piece, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a multimedia slide- show created between the 1970s and mid-1990s. Also included is Sisters, Saints & Sybils (2004), a slide and video exploration of her sister Barbara’s suicide at the age of 18. The accompanying essay is embargoed in English-speaking countries: 'I did not want my parents to read it,’ Goldin told me on a wonky landline from New York. During our conversation, I picked up the following Goldinisms and reflections, all communicated in her deep, throaty voice: On portraits: 'I realised a long time ago that outside of commercial work I would never photograph anyone that I didn’t want to live with. -

The International Center of Photography Announces Appointment of David E

THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY ANNOUNCES APPOINTMENT OF DAVID E. LITTLE AS NEW EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR New York, NY—August 10, 2021—The Board of Trustees of the International Center of Photography (ICP) announced today the selection of David E. Little as its new Executive Director, following an international search. Little will join ICP in mid-September 2021, after six years as director and chief curator of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, and will succeed Mark Lubell, who announced his departure in March 2021. “David brings to ICP an outstanding mix of skills and experiences, between his work as an educator, curator, fundraiser, and manager, and we are thrilled that he will be joining us,” said Jeffrey Rosen, ICP’s Board President. “His wide-ranging roles at leading institutions both within and outside of New York City make clear that he understands the different but interrelated elements of exhibitions, education, and community engagement that make ICP unique, which in turn made him the clear choice for our new Executive Director.” Little’s tenure at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst was marked by a record of successful fundraising, collection growth and diversification, and institutional planning that has strengthened the Mead’s curatorial program and its educational role within Amherst’s liberal arts curriculum. Little’s prior positions include time as the Curator and Department Head of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Associate Director and Head of Education at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Director of Adult and Academic Programs at the Museum of Modern Art. -

Words Without Pictures

WORDS WITHOUT PICTURES NOVEMBER 2007– FEBRUARY 2009 Los Angeles County Museum of Art CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 1 NOVEMBER 2007 / ESSAY Qualifying Photography as Art, or, Is Photography All It Can Be? Christopher Bedford 4 NOVEMBER 2007 / DISCUSSION FORUM Charlotte Cotton, Arthur Ou, Phillip Prodger, Alex Klein, Nicholas Grider, Ken Abbott, Colin Westerbeck 12 NOVEMBER 2007 / PANEL DISCUSSION Is Photography Really Art? Arthur Ou, Michael Queenland, Mark Wyse 27 JANUARY 2008 / ESSAY Online Photographic Thinking Jason Evans 40 JANUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Amir Zaki, Nicholas Grider, David Campany, David Weiner, Lester Pleasant, Penelope Umbrico 48 FEBRUARY 2008 / ESSAY foRm Kevin Moore 62 FEBRUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Carter Mull, Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 73 MARCH 2008 / ESSAY Too Drunk to Fuck (On the Anxiety of Photography) Mark Wyse 84 MARCH 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Bennett Simpson, Charlie White, Ken Abbott 95 MARCH 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Too Early Too Late Miranda Lichtenstein, Carter Mull, Amir Zaki 103 APRIL 2008 / ESSAY Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Alex Klein 120 APRIL 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Shannon Ebner, Phil Chang 131 APRIL 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Sarah Charlesworth, John Divola, Shannon Ebner 138 MAY 2008 / ESSAY Who Cares About Books? Darius Himes 156 MAY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Jason Fulford, Siri Kaur, Chris Balaschak 168 CONTENTS JUNE 2008 / ESSAY Minor Threat Charlie White 178 JUNE 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM William E. Jones, Catherine -

Larry Johnson

LARRY JOHNSON born 1959, Long Beach, CA lives and works in Los Angeles, CA EDUCATION 1984 MFA, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA 1982 BFA, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2019 Larry Johnson & Asha Schechter, Jenny's, Los Angeles, CA 2015 *Larry Johnson: On Location, curated by Bruce Hainley and Antony Hudek, Raven Row, London, England 2009 *Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA 2007 Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, CA Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York, NY 2001 New Photographs, Cohan, Leslie & Browne, New York, NY 2000 The Thinking Man’s Judy Garland and Other Works, Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, CA Modern Art Inc., London, England 1998 Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne, Germany I-20 Gallery, New York, NY Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1996 *Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 1995 Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] www.davidkordanskygallery.com T: 323.935.3030 F: 323.935.3031 1994 Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1992 Rudiger Shottle, Paris, France Patrick de Brok Gallery, Knokke, Belgium 1991 303 Gallery, New York, NY Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA Johnen & Schottle, Cologne, Germany 1990 303 Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Isabella Kacprzak, Cologne, Germany Stuart Regen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1989 303 Gallery, New York, NY 1987 Le Case d’ Arte, Milan, Italy 303 Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Isabella Kacprzak, Stuttgart, Germany Kuhlenschmidt/Simon Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1986 303 Gallery, New York, NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2021 Winter of Discontent, 303 Gallery, New York, NY The Going Away Present, Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2020 Made in L.A. -

Are You Cultured?

THERAPY OR ART? PHOTOGRAPHER LEIGH LEDARE CURATES THE HESSEL COLLECTION THE ARTIST WHO FIRST MADE WAVES WITH INTIMATE PORTRAITS OF HIS MOTHER DIGS INTO THE COLLECTION AT BARD, PULLING OUT WORKS BY STAR PHOTOGRAPHERS THAT EXPAND AND COMPLICATE HIS OWN PRACTICE. CALLAN MALONE ARE YOU0 6 . 2 2 . 2 0 1 9 CULTURED? “In no way is it therapy,” is the first thing Leigh Ledare makes clear when I ask him about his 2017 film, The Task. I tend toward the notion that everyone could use a little therapy, but after screening I’m thinking maybe everyone just needs a three-day group relation workshop. Okay, maybe it isn’t an alternative on its own, but The Task is certainly an uncomfortably close-up look at how people interact when asked to acknowledge how they’re interacting. Ledare’s work as a photographer and filmmaker have earned him a bit of a reputation. The 1998 work that first brought attention, “Pretend You’re Actually Alive,” whose photographs, texts and collected ephemera comprised a case study of his own family, centered centered around often lurid photographs of his mother’s complex sexuality, which she used to find companionship and a benefactor, to shield herself from her aging, and as an antagonism of her father’s, and society’s expectations of her as a daughter, mother and woman of her age. While Ledare makes a pivotal appearance in the film, The Task diverges from his earlier personal work. In another sense, however, it remains deeply personal, both for Ledare as well as for the 28 participants, 10 psychologists, and six camera operators who take part in the film. -

Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post- Mortem Photography

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post- mortem Photography https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40214/ Version: Full Version Citation: Summersgill, Lauren Jane (2016) Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography Lauren Jane Summersgill Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and, except for quotations, all of which have been clearly identified, was written entirely by me. Lauren J. Summersgill October 2014 3 Abstract This thesis investigates artistic post-mortem photography in the context of shifting social relationship with death in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyzing Nan Goldin’s Cookie in Her Casket and Andres Serrano’s The Morgue, I argue that artists engaging in post- mortem photography demonstrate care for the deceased. Further, that demonstrable care in photographing the dead responds to a crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in America. At the time, death returned to social and political discourse with the visibility of AIDS and cancer and the euthanasia debates, spurring on photographic engagement with the corpse. Nan Goldin’s 1989 post-mortem portrait of her friend, Cookie in Her Casket, was first presented within The Cookie Portfolio. -

Bertien Van Manen Give Me Your Image January 6 – February 18, 2006 Reception for the Artist: Thursday, January 5, 6-8 Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Bertien van Manen Give Me Your Image January 6 – February 18, 2006 Reception for the artist: Thursday, January 5, 6-8 pm A cross between Robert Frank and Nan Goldin with a little bit of Martin Parr…Bertien van Manen’s photographs - rich, textured, from-the-hip – might be described as a kind of visual anthropology. Jean Dykstra, Art Review, October 2005 The Yancey Richardson Gallery is pleased to present Give Me Your Image, an exhibition of photographs by Dutch photographer Bertien van Manen. Photographed throughout Europe between 2002 and 2005, these tightly composed intimate views of family photographs within domestic environments explore the role that family photographs play in our lives, how they shape our identity and form both personal history and shared history. Represented by this body of work, van Manen is one of four artists featured in the Museum of Modern Art's current exhibition, New Photography '05. In addition, our exhibition coincides with the release by Steidl Editions of the monograph Give me your Image, which presents the complete project. Originally commissioned by the Swiss Ministry for Foreign Affairs to photograph immigrants in the suburbs of Paris, van Manen ultimately expanded the project to the homes of individuals in countries as diverse as Lithunia, Greece, Germany, Italy, Austria, France, Bulgaria, Moldovia and Holland. Van Manen was intrigued by the photographs her subjects choose to keep and to display; the ones immigrants chose to take with them from their homelands; and the ones others chose to contain their memories and delineate their personal histories. -

Vantage Points: Contemporary Photography from the Whitney Museum of American Art

Vantage Points: Contemporary Photography from the Whitney Museum of American Art Organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, this exhibition features a selection of photographic works from the 1970s to the mid-2000s that highlights how photography has been used to represent individuals, places, and narratives. Drawn exclusively from the Whitney’s permanent collection, this presentation includes approximately twenty artists, including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Gregory Crewdson, William Eggleston, Nan Goldin, Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, and Andy Warhol. These artists began working at a time when photography was becoming increasingly integrated into the art world. Technological developments permitted them to use many different photographic processes and to print their works in various sizes, including ones that would create an immersive impact. The photographs included in this exhibition range from seemingly straightforward representations to those with an imaginative or conceptual perspective that challenge traditional notions of photography as revealing a singular reality. Many of the artists during this period used photography to portray their communities, friends, and themselves. Robert Mapplethorpe’s portraits highlight the physicality of his subjects, while those by Peter Hujar, Nan Goldin and Andy Warhol emphasize a personal intimacy. Diane Arbus’s photographs, such as Untitled #16 (1970-71), expose the relationship between the photographer and the subject as they reveal themselves to her. In Cerise (2002) Richard Artschwager transformed photographs taken of his subject from different angles into a three- dimensional freestanding form. Other artists portrayed the characteristics and poetics of place through photography. William Eggleston’s spontaneous color photographs, such as Untitled (Flowers in Front of Window) (c.