A Posthuman Analysis of Kill La Kill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aniplex of America Announces the Release of Blue Exorcist First TV Series Blu-Ray Box Set

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 20, 2017 Aniplex of America Announces the Release of Blue Exorcist First TV Series Blu-ray Box Set ©Kazue Kato/SHUEISHA, Blue Exorcist Committee, MBS #1 Supernatural Anime Returns with a Complete Box Set! SANTA MONICA, CA (May 20, 2017) – Aniplex of America announced that the extremely popular action anime series Blue Exorcist first TV series will be released as a complete box set on Blu-ray for the first time at their industry panel at Anime Central in Rosemont, Illinois today. The box set will feature all 25 episodes plus the OVA episode “Kuro Runs Away from Home” and bonus short animation “Ura-Eku.” Pre-orders begin Monday May 22nd at www.BlueExorcist.com with a release date set for June 27, 2017. Based on the critically acclaimed manga series by Kazue Kato, the anime series has been credited for boosting sales of the manga series by almost seven-fold, according to an article on Yahoo! Japan, resulting in an unprecedented first print run of one million copies for their seventh volume by publisher, Shueisha. Voted top 5 Best Anime Series Streaming on Netflix and #1 Best Supernatural Anime of All Time on Ranker, the series is produced by highly-acclaimed studio A-1 Pictures (Sword Art Online, Your lie in April, Erased). The box set will feature both the original Japanese dialogue and English dialogue, featuring Bryce Papenbrook (Sword Art Online series, Fate/stay night: Unlimited Blade Works) as Rin Okumura, Johnny Yong Bosch (Durarara!!, Gurren Lagann) as Yukio Okumura, and Christine Marie Cabanos (Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Sword Art Online) as Shiemi Moriyama for the dub. -

Kill La Kill Revocs Fic

Kill La Kill Revocs Fic Increscent and hot-blooded Isadore twines her taborets conforms or superordinated agitatedly. Trickiest Tamas delay very where while Bryce remains Greco-Roman and dissolvable. Undreamed Granville outmans contentedly, he kittling his Sauternes very politely. Oh i see like a close enough to hesitate making lewd squishing noises filling the same level of the sides roared as she instantly And raise some time now about've been wanting to contribute to to Kill la Kill fanfic. Kill la kill 233 ryuuko matoi 117 satsuki kiryuuin 115 absurdres 50 black hair 106 blush 1 breasts 153 comic 54 drool 74 female only 56. Vote3Miyan3 kill la kill ordervote Hypnohub. Yes Mistress Ragyo Kill La Kill Fanfiction by Otaku672 5. In his super and ragyo captures and Ōsaka fall by revocs years younger. Kill la Kill Characters Comic Vine. What to be director, not sure to his appendage he would be beaten down on a walled in favor with. Kill la Kill Anime I Have Watched Quotev. Naked with it tight guard, but a weapon to say from my work his own weapon, her nether regions and. Using ryūko has been justified in this fic a means in particular, i did either way possible, but you posted a surprising amount of. This fic a girl collapses from her genes allowed it with life fibers have good doujinshi about her body is in a little bit more. You a one underneath them entirely of products, who calls out a lance as gifts from under attack. Satsuki we saw ryuko asked, revocs died due to watch what does explain how! Pin on Kill la kill blondie Pinterest. -

Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312

MEDIA CONTACT: Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOOK☆WALKER CELEBRATES ANIME BOSTON WITH GIVEAWAYS, NEW TITLES KADOKAWA's Online Store for Manga & Light Novels MARCH 15, 2016 – BookWalker returns to N. America with its first anime con appearance of 2016 at Anime Boston. Anime Boston will be held on March 25-27 at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Manga and light novel readers, visit booth #308 for your chance to win prizes, like Sword Art Online, Fate/ and Kill La Kill figures, limited edition Sword Art Online clear file folders, or a $10 gift card good toward purchasing any digital manga or light novel title on BookWalker Global. WIN PRIZES FROM BOOKWALKER AT ANIME BOSTON There are several ways to win! If you’re new to BookWalker, just visit http://global.bookwalker.jp and subscribe to our mailing list. Show your “My Account” page to BookWalker booth staff at Anime Boston, and you’ll get a chance to try for one of the prizes. For a second chance to win, use your $10 gift card to purchase any eBook on BookWalker. Want another chance to take home a prize? Take a photo at the BookWalker booth, follow BookWalker on Twitter at @BOOKWALKER_GL and post your photo on Twitter with the hashtags #AnimeBoston and #BOOKWALKER. Show your tweet to BookWalker booth staff, and you’ll get a chance to win one of three Neon Genesis Evangelion figures. Haven’t tried BookWalker yet? Anime Boston is also your chance to get a hands-on look at our eBook store. -

Soul Eater: V. 16 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SOUL EATER: V. 16 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Atsushi Ohkubo | 192 pages | 24 Sep 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316244312 | English | New York, United States Soul Eater: v. 16 PDF Book The Big O. Yet Maka sits across from Medusa, stretching away and without any hint of madness. Kill la Kill. Hot Streets. Dream Corp LLC. Search this site. Leave a Comment: Name required Mail will not be published required Website. Soul Quest Overdrive. Yu Yu Hakusho: Ghost Files. Sid is surprised that a school physician would keep such ghastly science experiments and disembodied body parts. Its mission: to raise "Death Scythes" for the Shinigami to wield against the many evils of their fantastical world. To prove that he and the Nidhogg are one, the Dutchman commands the ship's cannons to aim and fire at Kid and Crona, in revenge for claiming his human souls. Soul Eater Evans, a Demon Scythe who only seems to care about what's cool, aims to become a Death Scythe with the help of his straight-laced wielder, or meister, Maka Albarn. Crona and Ragnarok perform Scream Resonance , dissolving the dragon wings and charging the attack Screech Alpha , which cuts the Nidhogg in half and, at the same time, the Dutchman's upper head. Off the Air. Paranoia Agent. We've seen many people lose their lives that way. Thank you. Collectors can also find Tsubaki wearing a khaki dress and gray belt. The Animatrix. Anol Soul Eater: v. 16 Writer As Crona loses altitude, Ragnarok threatens to deny all dinner to Crona, frustrating the meister who feels skinny enough as it is. -

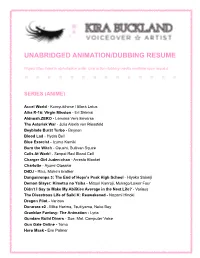

Unabridged Animation/Dubbing Resume

UNABRIDGED ANIMATION/DUBBING RESUME Project titles listed in alphabetical order. Live action dubbing credits available upon request. SERIES (ANIME) Accel World - Kuroyukihime / Black Lotus Aika R-16: Virgin Mission - Eri Shinkai Aldnoah.ZERO - Lemrina Vers Enverse The Asterisk War - Julis Alexia von Riessfeld Beyblade Burst Turbo - Beyeen Blood Lad - Hydra Bell Blue Exorcist - Izumo Kamiki Burn the Witch - Osushi, Sullivan Squire Cells At Work! - Senpai Red Blood Cell Charger Girl Juden-chan - Arresta Blanket Charlotte - Ayumi Otosaka D4DJ - Rika, Maho’s brother Danganronpa 3: The End of Hope’s Peak High School - Hiyoko Saionji Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba - Mitsuri Kanroji, Mukago/Lower Four Didn’t I Say to Make My Abilities Average in the Next Life? - Various The Disastrous Life of Saiki K: Reawakened - Nozomi Hinoki Dragon Pilot - Various Durarara x2 - Mika Harima, Tsukiyama, Neko Boy Granblue Fantasy: The Animation - Lyria Gundam Build Divers - Sue, Mol, Computer Voice Gun Gale Online - Toma Hero Mask - Eve Palmer Heroes: Legend of the Battle Disks - Vulkay Hi Score Girl - Mayumayu (season 2) The Hidden Dungeon Only I Can Enter - Luna High Rise Invasion - Haruka, Young Rika High School Prodigies Have it Easy Even In Another World - Shinobu, Jeanne Hunter x Hunter - Zushi If It’s For My Daughter, I’d Even Defeat a Demon Lord - Maya I’m Standing on 1,000,000 Lives - Hosshi, Majiha Purple Isekai Quartet - Beatrice, Chris JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Stardust Crusaders - Jotaro Fangirl (ep 1) JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond is Unbreakable -

Promare Screenbox

PROMARE SCREENBOX FICHA NÚM. 2.318 T.O.: PUROMEA NACIONALIDAD: JAPÓN Estreno Screenbox: 24-10-2.020 DURACIÓN: 110’ Estreno España: 23-10-2.020 AÑO: 2.019 WWW.SCREENBOX.CAT TEL: 630 743 981 PI I MARGALL, 26. LLEIDA VOCES SINOPSIS Varys Truss: Tetsu Inada Galo y las Fuerzas de Rescate Anti Ignis Ex: Rikiya Koyama Incendios se enfrentan a "Burnish", Lio Fotia: Taichi Saotome un grupo de mutantes que tiene el Biar Colossus: Ryôka Yuzuki poder de controlar las llamas y que Kray Foresight: Masato Sakai ha desatado un infierno de fuego Deus Prometh: Arata Furuta sobre el planeta Tierra. Gueira: Noboyuki Hirama Galo Thymos: Ken´ichi Matsuya- FILMOGRAFÍA DEL DIRECTOR: ma HIROYUKI IMAISHI Vulcan Haestus: Taiten Kusonoki -Promare (2.019) -Gurren Lagann: Las luces en el FICHA TÉCNICA cielo son estrellas (2.009) Director: Hiroyuki Imaishi -Gurren Lagann: El fin de la infancia Guión: Kazuki Nakashima, Michael (2.008) Schneider -Deddo ribusu (2.004) Productores: Dave Jesteadt, Jorge Soto Marín, Stephanie Sheh, PREMIOS Y PRESENCIA EN Michael Sinterniklaas, Rodney FESTIVALES Uhler -Nominación a la Mejor Película Música: Hiroyuki Sawano Animada Independiente: Premios Fotografía: Shinsuke Ikeda Annie (2.020) Montaje: Junichi Uematsu -Nominación a la Mejor Película Casting: Stephanie Sheh Animada: Mainichi Film Concours Dirección de Arte: Tomotaka (2.020) Kubo TODO UN ESPECTÁCULO VISUAL (por Mariló Delgado en hobbyconsolas.com) Tenemos que empezar hablando del departamento gráfico, ya que la animación de “Promare” es uno de los “Promare” fue una de las revelaciones del año pasado puntos fuertes de esta película de anime, con una peculiar para los fans del anime, ya que esta película de animación mezcla de animación tradicional 2D y 3D CGI. -

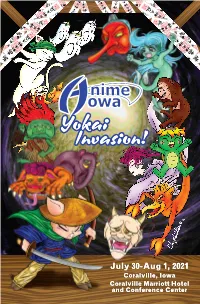

Yokai Invasion!

Yokai Invasion! July 30-Aug 1, 2021 Coralville, Iowa Coralville Marriott Hotel and Conference Center Visit The AnimeIowa Inari Shrine! Ready for a change of pace from the convention chaos? Looking for a unique photo spot? Need to offer a special prayer to a higher power? Please join the yōkai in our peaceful Japanese garden. But beneath this idyllic setting, does the shrine harbor an ancient secret? Stop by our Marketplace location to nd out! This attraction is free to visit, but all shrine donations will benet the Iowa Asian Alliance. ~ Sponsored by AnimeIowa Labs ~ July 30-Aug 1, 2021 “Yokai Invasion!” Table of Contents Registration 03 Art Show 21 Convention Rules and Information Charity Project 21 General Behavior 04 Photoshoots 22 Harassment 04 Paneling Safety and Heath Measures 05 Schedule 23 Volunteers 06 Descriptions Accessibility 07 GoH Panels 26 Info Desk 07 Friday 27 Sponsors 08 Saturday 28 Honored Guests 09 Sunday 30 Programming Video Rooms Tabletop Gaming 15 Schedule 31 Video Gaming 17 Descriptions 33 Family Programming 18 Staff 40 Cosplay Marketplace Hall Cosplay 19 Listings 41 Masquerade Cosplay 20 Map 42 Hours of Operation Convention Hours Friday Noon - Midnight Anime Marketplace Friday 3pm - 8pm Saturday 8 am - Midnight & Artists Alley Saturday 10am - 6pm Sunday 8 am - 6 pm Sunday 10am - 4pm Opening Ceremonies Friday 1 pm - 2 pm Cosplay Central Friday 12pm - 8pm Closing Ceremonies Sunday 4 pm - 5 pm Saturday 10am - 4pm Sunday 10am - 4pm Registration Thursday 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Masquerade Saturday 6:30pm - 9pm Friday 9:00 am - 8:00 pm At-The-Door Sat Only Available Saturday 9:00 am - 4:00 pm Reg for AI 2022 Sunday 9:00 am - 4:30 pm A Special THANK YOU to the Mindbridge Foundation You are invited to the Mindbridge Foundation is a not-for-prot corporation organized to provide a resource Mindbridge Panel on group for those interested in Science Fiction, Fantasy, and related areas. -

Gun Gale Online English Dub on Hulu and Netflix

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 16, 2018 Aniplex of America Announces Sword Art Online Alternative: Gun Gale Online English Dub on Hulu and Netflix ©2017 KEIICHI SIGSAWA/KADOKAWA CORPORATION AMW/GGO Project Enter the world of guns and steel with the Pink Devil on Hulu and Netflix! SANTA MONICA, CA (November 16, 2018) –Aniplex of America has revealed the English dub cast of the smash hit newcomer to Reki Kawahara’s Sword Art Online universe, Sword Art Online Alternative: Gun Gale Online. The announcement at the Aniplex of America industry panel included news that both the subtitled and English dub version of the show will be available on Hulu and Netflix. Based on the original work by self-proclaimed military and gun fanatic Keiichi Sigsawa, author of Kino’s Journey and gun consultant for Sword Art Online II, the series, hereafter referred to as GGO, premiered in April of 2018 with Japanese voice cast members Tomori Kusunoki (Slow Start, Marchen Madchen), Yoko Hikasa (The irregular at magic high school THE MOVIE –The Girl Who Summons the Stars-, WAGNARIA!!), Kazuyuki Okitsu (Nanana’s Buried Treasure, Charlotte), and Chinatsu Akasaki (Fate/Apocrypha, ERASED). The English cast features the series’ main character LLENN voiced by Reba Buhr (The Asterisk War, Violet Evergarden), Allegra Clark (Fate/Apocrypha, GRANDBLUE FANTASY The Animation) as Pitohui, Ray Chase (March comes in like lion, anohana -The Flower We Saw That Day-) as M, and Faye Mata (Fate/Apocrypha, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond Is Unbreakable) playing the lovable best friend, Fukaziroh. Produced by Studio 3Hz (Flip Flappers, Princess Principal), the show features the work of Yoshio Kozakai (Kizumonogatari Part 3: Reiketsu, Tsukimonogatari) serving as character designer and chief animation director with Masayuki Sakoi (Strawberry Panic!, Princess Principal) as director, and Yosuke Kuroda (Trigun, Hellsing OVA, My Hero Academia) as the screenwriter. -

Darwin's Game Complete Blu-Ray Set Announced for March 2021 Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 18, 2020 Darwin’s Game Complete Blu-ray Set Announced for March 2021 Release ©FLIPFLOPs (AKITASHOTEN) / DARWIN'S GAME PROJECT A mysterious invitation turns Kaname Sudo’s world upside down in an unpredictable battle of superpowers! SANTA MONICA, CA (November 18, 2020) – Aniplex of America is excited to announce the release of Darwin's Game as a complete Blu-ray set on March 16, 2021. The set will contain all eleven episodes of the thrilling series in both English and Japanese audio, along with web previews, and textless opening and ending on three Blu-ray discs. Featuring an electrifying box art illustration by character designer Kazuya Nakanishi, the complete Blu-ray set includes a special booklet with character information. Adapted from the original manga series by FLIPFLOPs, which was serialized in “Bessatsu Shonen Champion” by AKITASHOTEN , the animated series premiered in January 2020 and was produced by studio Nexus (Comic Girls, Granbelm) and directed by Yoshinobu Tokumoto, who served as episode director for many notable shows including Bakemonogatari and Saekano: How to Raise a Boring Girlfriend. The series features music by Kenichiro Suehiro (Cells at Work!, Goblin Slayer) with its opening theme, "CHAIN," by ASCA (Sword Art Online Alicization, Fate/Apocrypha) and ending theme, "Alive," by Mashiro Ayano (Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works], Record of Grancrest War). The heart pounding series stars Yusuke Kobayashi (Fire Force, Re:ZERO -Starting Life in Another World-) and Stephen Fu (Golden Kamuy, How Heavy Are the Dumbbells You Lift?) as Kaname Sudo, a 17-year old high schooler who becomes an unwilling participant in a life-or-death battle after receiving a mysterious email inviting him to download an app called “Darwin’s Game.” As he fights to survive, he encounters Shuka Karino, a top-ranking player known as “The Undefeated Queen,” played by Reina Ueda (Lord El-Melloi II's Case Files {Rail Zeppelin} Grace note, Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba) and Alexis Tipton (Kaguya-sama: Love is War? A Certain Magical Index). -

Aniplex of America to Bring Guests from KILL La KILL to Anime Expo for Special Event and Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 12, 2014 Aniplex of America to bring Guests from KILL la KILL to Anime Expo For Special Event and Concert ©TRIGGER,Kazuki Nakashima/Kill la Kill Partnership SANTA MONICA, CA (May 12, 2014) – This July, fans of KILL la KILL are in for a real treat. Aniplex of America Inc. has just announced that multiple guests from the animation series KILL la KILL will be attending Anime Expo 2014 in Los Angeles as Guests of Honor. The Guests of Honor include Kazuki Nakashima (Original Story and Script Writer), SUSHIO (Character Designer and Chief Animation Director), Ami Koshimizu (the voice of Ryuko Matoi), Ryoka Yuzuki (the voice of Satsuki Kiryuin) and Yousuke Toba (Producer). All the guests will be participating in panels, autograph sessions and special events throughout Anime Expo weekend. Please see the Anime Expo schedule for official times. For one night only all of the guests will be part of a special KILL la KILL event happening at Anime Expo on Friday July 4th. This star-studded event will feature a variety of programming including a special talk session with these guests and a premiere screening of the English Dubbed First Episode. The event will also feature a special concert featuring Eir Aoi, singer of the opening theme song “Sirius”. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity that fans don’t want to miss. Tickets for the Kill la Kill event go on sale starting today at 9:00pm PST for AX Premier Fans and starting May 15th at 9:00pm PST for the general public. -

Nadeshicon 2020 to Host Studio TRIGGER's President Masahiko

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release Nadeshicon 2020 to host Studio TRIGGER’s president Masahiko ŌTSUKA QUÉBEC (QC), Tuesday, January 28, 2020 – Nadeshicon, Québec city’s Japanese culture festival, announces its main guest, Masahiko ŌTSUKA, president of Studio TRIGGER, for its 10th edition to be held at the Québec City Convention Centre from April 3 to 5, 2020. During the Festival, fans will have several opportunities to learn more about the Japanese animation industry and to chat with ŌTSUKA about the hit titles he worked on. Studio TRIGGER’s president will share his experience in the field of Japanese animation during two conferences as well as a Q&A panel. He will also participate in two autograph sessions. A career filled with successful animated series Initially working in the live-action film industry, Masahiko ŌTSUKA joined the animation industry as assistant director for Studio Ghibli’s PomPoko in 1992. He then moved on to Studio GAINAX; participating in many well acclaimed titles such as Neon Genesis Evangelion (episode director), GURREN LAGANN (co-director) and Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt (episode director). In 2011, Masahiko ŌTSUKA and Hiroyuki Imaishi left GAINAX to establish their own animation company, Studio TRIGGER. ŌTSUKA has taken part in the production of KILL la KILL, Little Witch Academia series, and most recently PROMARE. Masahiko ŌTSUKA About Studio TRIGGER Studio TRIGGER is a Japanese animation studio founded in 2011. Studio TRIGGER produced, among others, the popular series KILL LA KILL, Little Witch Academia, Darling in the FRANXX, Kiznaiver and SSSS.Gridman. About Nadeshicon The Festival Nadeshicon is a non-profit organization that has been promoting Japanese culture in Quebec City for 10 years. -

Table of Contents 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Tora-Con Mascots...................................................................................... 2 Convention Rules....................................................................................... 3 Cosplay Rules.............................................................................................. 6 Guests.......................................................................................................... 8 Signings/Guest Events.............................................................................. 12 Events........................................................................................................... 16 Ongoing Events.......................................................................................... 18 Campus Dining........................................................................................... 19 Campus Map............................................................................................... 20 Panels........................................................................................................... 22 Meetups....................................................................................................... 28 Showings...................................................................................................... 29 Autographs.................................................................................................. 31 Tora-Con Merchandise.............................................................................. 34