Attachment B: Scoping Study on Water Issues in Remote Aboriginal Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Store Nutrition Report and Market Basket Survey.Pdf

Store Nutrition Report and Market Basket Survey April 2014 Nganampa Health Council Erin McLean, Kate Annat and Prof Amanda Lee April 2014 Executive Summary The report provides Market Basket pricing and data analysis of Mai Wiru compliance with standardised food and nutrition checklists from stores on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in South Australia collected in April 2014. The report focuses on the Mai Wiru group stores (Pipalyatjara, Kanpi, Amata, Fregon and Pukatja). Pricing data was also collected from Mimili (Outback Stores), Indulkana (independent) and Coles and IGA Foodlands supermarkets in Alice Springs. The purpose of this report is to provide key recommendations for Mai Wiru store councils to aid decision-making regarding food and nutrition issues. Data was collected in-store from 7-11 April 2014. Information was collected on the price, availability and promotion of foods, as well as Mai Wiru store achievement of the Remote Indigenous Stores and Takeaways (RIST) checklist benchmarks and implementation of nutrition recommendations from the previous Market Basket report (September, 2013). Nutrition promotion activities were also performed in all the Mai Wiru stores, including one pot cooking demonstrations and installation of sugar-in-food displays and posters. Results show that, in April 2014, Mai Wiru stores: • Are clean, functional and well stocked; • Provide a wide range of healthy foods and beverages; and • Price healthy foods at a competitive rate for remote areas. In April 2014 the average price of the Market Basket in the Mai Wiru stores was $734 dollars and had increased only 0.3% since September 2014. In comparison to the other stores monitored during the same period the Mai Wiru store prices were 4.3% less than Mimili, 1.0% more than Indulkana, only 13.0% more than Alice Springs IGA Foodlands and 34.4% more than Coles. -

A Long Way to Go in Nuclear Debate, Says Aboriginal Congress of SA

Aboriginal Way Issue 60, Spring 2015 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Aboriginal Congress of South Australia A long way to go in nuclear debate, says Aboriginal Congress of SA In early August, the Aboriginal During July and August, the Royal Parry Agius, Alinytjara Wiluara Natural waste dump” and the Royal Commission Congress of South Australia Commission engaged regional and Resources Board Member reinforced the is nothing more than mere formality. convened in Port Augusta to remote communities including Coober notion of an appropriate timeline in his Karina Lester, Aboriginal Congress discuss the issues and concerns Pedy, Oak Valley, Ceduna, Port Lincoln, submission. Mr Agius wrote, “we note of SA member said it is clear by the of potential expansion of uranium Port Augusta, Whyalla, Port Pirie, levels of concern within our communities submissions to the Royal Commission mining in SA, including the Ernabella, Fregon, Mimili, Indulkana, that suggest that the timeframe for that Aboriginal People do not support development of a nuclear Ceduna, Amata, Kanpi and Pipalyatjara. consultation on the risks and opportunities the Nuclear Fuel Cycle. waste dump. through the Royal Commission is Aboriginal Congress of SA Chair, insufficient”. Through the initial “Our views are clear in the submissions The State Government launched a Tauto Sansbury said the engagement conversations with community members and we need to ensure that this gets public inquiry on the Nuclear Fuel Cycle with Aboriginal Communities is there is, he added, “a level of confusion across to the Commissioner. We need by calling a Royal Commission in March. welcomed however the consultation about what was being discussed”. -

Indigenous Design Issuesceduna Aboriginal Children and Family

INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWELDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND “BEST PRACTICE„ DESIGN ....................................................10 The Design of Early Learning, Child-care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ..................................................................................................................................10 Conceptions of Quality ........................................................................................................ 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ..................................12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................................. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

PITJANTJATJARA Council Inc. FINDING

PITJANTJATJARA MS 1497 PITJANTJATJARA Council Inc. FINDING AID Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 1497 PITJANTJATJARA COUNCIL ARCHIVES A3a/B1 Minutes of meetings of the Pitjanjatjara Council 1976-1981 Originals and copies (see also MS 1168) In English and Pitjantjatjara Contents: I. Pitjantjatjara Council Inc. Minutes of meetings (originals) 1) Amata, SA, 13 July 1976, 11 p., map 2) Docker River, NT, 7 September 1976, 6p. 3) Ipdulkana, 1 December 1976, 8p. 4) Blackstone (Papalankutja), WA, 22-23 February 1977, 12p. 5) Ernabella (Pukatja), SA, 19-20 April 1977, 5p. 6) Warburton, WA, 21 -22 June 1977, 10p. 7) Amata, SA, 3 August 1977, 4p. (copy) 8) Ernabella, SA, 26-27 September 1977, 4p. 9) Puta Puta, SA, 28-29 November 1977, 7p. 10) Fregon, SA, 21-22 February 1978, 9p. 11) Mantamaru (Jamieson), WA, 2-3 May 1978, 6p. 12) Pipalyatjara, SA, 17-18 July 1978, 6p. 13) Mimili, SA, 3-4 October 1978, 10p. 14) Uluru (Ayers Rock), NT, 4-5 December 1978, 6p. 15) Irrunytju (Wingelinna), 7-8 February 1979, 6p. 16) Amata, SA, 3-4 April 1979, 6p. • No minutes issued for June and August 1979 meetings 17) Nyapari, SA, 15-16 November 1979, 9p. 18)lndulkana, 10-11 December 1979, 6p. 19) Adelaide, SA, 13-14 February 1980, 6p. 20) Adelaide, SA, 13-14 February 1980 - unofficial report by WH Edwards, 2p. 21) Blackstone (Papulankutja), WA, 17-18 April 1980,3p. 22) Jamieson (Mantamaru), WA, 22 July 1980, 4p. 23) Katjikatjitjara, 10-11 November 1980, 4p. (copy) 24) Docker River, 9-11 February 1981, 5p. -

Presentation Tile

Authentic and engaging artist-led Education Programs with Thomas Readett Ngarrindjeri, Arrernte peoples 1 Acknowledgement 2 Warm up: Round Robin 3 4 See image caption from slide 2. installation view: TARNANTHI featuring Mumu by Pepai Jangala Carroll, 2015, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; photo: Saul Steed. 5 What is TARNANTHI? TARNANTHI is a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists from across the country to share important stories through contemporary art. TARNANTHI is a national event held annually by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Although TARNANTHI at AGSA is annual, biannually TARNANTHI turns into a city-wide festival and hosts hundreds of artists across multiple venues across Adelaide. On the year that the festival isn’t on, TARNANTHI focuses on only one feature artist or artist collective at AGSA. Jimmy Donegan, born 1940, Roma Young, born 1952, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, 1940–2018, Brenton Ken, born 1944, Witjiti George, born 1938, Sammy Dodd, born 1946, Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Freddy Ken, born 1951, Naomi Kantjuriny, born 1944, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, born 1940, Willy Kaika Burton, born 1941, Rupert Jack, born 1951, Adrian Intjalki, born 1943, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, c.1930–2016, Arnie Frank, born 1960, Stanley Douglas, born 1944, Maureen Douglas, born 1966, Willy Muntjantji Martin, born 1950, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, born 1940, Noel Burton, born 1994, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, 1937–2017, -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

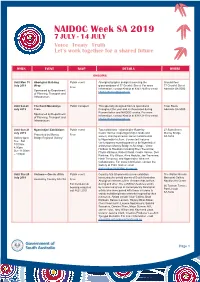

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice . Treaty . Truth Let’s work together for a shared future WHEN EVENT RSVP DETAILS WHERE ONGOING Until Mon 15 Aboriginal Building Public event Aboriginal graphic design is covering the Ground floor July 2019 Wrap glass windows of 77 Grenfell Street. For more 77 Grenfell Street Free information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email Adelaide SA 5000 Sponsored by Department [email protected] of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Until Sat 20 The Kardi Munaintya Public transport This specially designed tram is operational Tram Route July 2019 Tram throughout the year and is showcased during Adelaide SA 5000 Reconciliation and NAIDOC weeks. For more Sponsored by Department information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email of Planning, Transport and [email protected] Infrastructure Until Sun 21 Ngarrindjeri Exhibitions Public event Two exhibitions - Ngarrindjeri Ruwe by 27 Sixth Street July 2019 Cedric Varcoe maps Ngarrindjeri lands and Murray Bridge Presented by Murray Free waters, sharing ancestor stories fundamental SA 5253 Gallery open Bridge Regional Gallery to Ngarrindjeri culture. Connected features Tue - Sat contemporary weaving practices by Ngarrindjeri 10:00am – artists from Murray Bridge to Meningie, Victor 4:00pm Harbour to Raukkan including Ellen Trevorrow, Sun 11:00am Phyllis Williams, Robert Wuldi, Cedric Varcoe, Deb – 4:00pm Rankine, Elly Wilson, Alice Abdulla, Joe Trevorrow, Hank Trevorrow, and Ngarrindjeri Weavers Collaborators. For more information, contact the Gallery at 8539 1420 or email [email protected] Until Thu 25 Vietnam – One In, All In Public event Country Arts SA presents a new exhibition The Walter Nichols July 2019 honouring the untold stories of South Australian Memorial Gallery Hosted by Country Arts SA Free Aboriginal veterans of the Vietnam War, before, Nautilus Art Centre For Port Lincoln during and after. -

South Australian Multiple Land Use Framework-Pepinnini Minerals Community Engagement in the APY Lands, Case Study 4

Government of South Australia South Australian Multiple Land Use Framework PEPINNINI MINERALS COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN THE APY LANDS CASE STUDY 4 www.yoursay.sa.gov.au South Australian Multiple Land Use Framework Synopsis What is the issue? – Ensuring that exploration companies engage well and develop the trust of the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people (Anangu) so that exploration activities do not detrimentally impact on the Anangu’s ability to manage the natural and cultural values of the land. What was the resolution? – The development of strong connections and ongoing partnerships has ensured that the Anangu have benefited socially, economically and environmentally from the exploration activities through local employment, training, support for social events and educational opportunities. Multiple uses PepinNini Minerals Limited is an Australian ASX listed exploration company based in Adelaide (http://www.pepinnini.com.au/). It has a diverse commodity portfolio with projects in both Australia and Argentina. PepinNini currently has an interest in 11 exploration tenements in South Australia covering approximately 14,393km2. Of these tenements, two exploration licences and eight exploration licence applications are located in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yunkunytjatjara (APY) Lands. PepinNini has been actively exploring in the APY Lands for nickel, copper and PGE (platinum group elements) as well as lead, zinc and gold for approximately ten years and has developed strong connections and partnerships with the Anangu. PepinNini has its own purpose built field camp from which its drilling crew operates and maintains its own diamond drilling rig and vacuum rig. The APY Lands are located in the far northwest of APY Lands South Australia and consist of approximately 103,000 km2 of land (or around 10.5% of the State). -

Tough(Er) Love Art from Eyre Peninsula

tough(er) love art from Eyre Peninsula COUNTRY ARTS SA LEARNING CONNECTIONS RESOURCE KIT AbOUT THIS RESOURCE KIT This Resource kit is published to accompany the exhibition tough(er) love: art from Eyre Peninsula at the Flinders University City Gallery, February 23 – April 28 2013 and touring regionally with Country Arts SA 2013 – 2015. This Resource kit is designed to support learning outcomes and teaching programs associated with viewing the tough(er) love exhibition by: • Providing information about the artists • Providing information about key works • Exploring Indigenous perspectives within contemporary art • Challenging students to engage with the works and the exhibition’s themes • Identifying ways in which the exhibition can be used as a curriculum resource • Providing strategies for exhibition viewing, as well as pre and post-visit research • It may be used in conjunction with a visit to the exhibition or as a pre-visit or post-visit resource. ACKNOWLEdgEMENTS Resource kit written by John Neylon, art writer, curator and arts education consultant. The writer acknowledges the particular contribution of all the artists and the following people to the development of this resource: COUNTRY ARTS SA Craig Harrison, Manager Artform Development Jayne Holland, Development Officer Western Eyre Penny Camens, Coordinator Arts Programs Anna Goodhind, Coordinator Visual Arts Pip Gare, Web and Communications Officer Tammy Hall, Coordinator Audience Development Beth Wuttke, Graphic Designer FLINDERS UNIVERSITY Fiona Salmon, Director Flinders University Art Museum & City Gallery Celia Dottore, Exhibitions Manager TOUGH(ER) LOVE RESOURCE KIT 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS BACKGROUND . 4 About this exhibition ............................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND The Artists ......................................................................................... 4 BEHIND THE SCENES The Curator ....................................................................................... -

Far Removed: an Insight Into the Labour Markets of Remote Communities in Central Australia

145 AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF LABOUR ECONOMICS VOLUME 19 • NUMBER 3 • 2016 Far Removed: An Insight into the Labour Markets of Remote Communities in Central Australia Michael Dockery, Curtin Business School Judith Lovell, Charles Darwin University Abstract There are ongoing debates about the livelihoods of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians living in remote communities, and the role for policy in addressing socio- economic equity and the economic viability of those communities. The characteristics and dynamics of remote labour markets are important parameters in many of these debates. However, remote economic development discourses are often conducted with limited access to empirical evidence of the actual functioning of labour markets in remote communities – evidence that is likely to have important implications for the efficacy of policy alternatives. Unique survey data collected from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders living in 21 remote communities in central Australia for the Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation’s Population Mobility and Labour Markets project are used to examine these labour markets, with a focus on the role of education and training. Examining access to education, employment opportunity and other structural factors, it is clear that the reality of economic engagement in these communities is far removed from the functioning of mainstream labour markets. The assumptions about, or lack of distinction between remote and urban locations, have contributed to misunderstanding of the assets and capabilities remote communities have, and aspire to develop. Evidence from the survey data on a number of fronts is interpreted to suggest policies to promote employment opportunity within communities offer greater potential for improving the livelihoods of remote community residents than policies reliant on the assumption that residents will move elsewhere for work.