3624.Pdf (477.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2021 Quarter Two: January 1 – March 31, 2021

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2021 Quarter Two: January 1 – March 31, 2021 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. Program Title: Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID DRC Contract Number: AID-660-C-17-00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: April 30, 2021 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 ACTIVITY OVERVIEW / SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 SUMMARY OF RESULTS TO DATE 7 EVALUATION / ASSESSMENT STATUS AND/OR PLANS 10 ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS 13 INTEGRATION OF CROSSCUTTING ISSUES AND USAID FORWARD PRIORITIES 33 STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION AND INVOLVEMENT 45 MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES 46 MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND LEARNING 46 SPECIAL EVENTS FOR NEXT QUARTER 48 HOW USAID IGA HAS ADDRESSED A/COR COMMENTS FROM THE LAST QUARTERLY OR SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT 48 FINANCIAL SUMMARY 48 ANNEXES 49 ANNEX A. -

Province Du Nord Kivu

Plan Quinquennal de Croissance et de l’emploi 2011-2015 Nord-Kivu 1 CARTE DE LA PROVINCE DU NORD- KIVU Plan Quinquennal de Croissance et de l’emploi 2011-2015 Nord-Kivu 2 TABLE DES MATIERES TABLE DES MATIERES .............................................................................................................................. 3 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................................... 7 LISTE DES GRAPHIQUES ........................................................................................................................... 7 SIGLES ET ACRONYMES ........................................................................................................................... 8 PREAMBULE ........................................................................................................................................... 11 RESUME EXECUTIF ................................................................................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 14 CHAPITRE 1 : PRESENTATION DE LA PROVINCE .................................................................................... 16 1.1. Contexte physique ................................................................................................................. 16 1.2. Contexte administratif.......................................................................................................... -

Fonds Social De La Republique Democratique Du Congo (Fsrdc)

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO (RDC) FONDS SOCIAL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO (FSRDC) PROJET POUR LA STABILISATION DE L’EST POUR LA PAIX (STEP) Projet d’Inclusion Productive avance de Préparation de Projet (PIP-APP) Projet d’Éducation pour la Qualité et la Pertinence des Enseignements aux niveaux Secondaires et Universitaires (PEQPESU) composante de réponse à l’Urgence (PEQPESU-CERC) CADRE DE POLITIQUE DE REINSTALLATION MIS A JOUR POUR LE PROGRAMME STEP/PIPAPP/PEQPESU.CERC (CPR) RAPPORT FINAL AOUT 2019 1 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES PRINCIPALES ABREVIATIONS 6 GLOSSAIRE 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12 RESUME EXECUTIF 17 1. INTRODUCTION 23 1.1 CONTEXTE DE LA MISSION 23 1.2 OBJECTIF DU CPR 25 1.3 MÉTHODOLOGIE 26 1.4 CONTENU DU RAPPORT 27 2. DESCRIPTION DU PROJET 29 2.1 OBJECTIFS ET JUSTIFICATION DU PROJET 29 2.2 COMPOSANTES DU PROJET 29 2.3 COMPOSANTES ABOUTISSANT À LA RÉINSTALLATION DES POPULATIONS ERREUR ! SIGNET NON DEFINI. 3. IMPACTS POTENTIELS DU PROJET SUR LES PERSONNES ET LES BIENS 34 3.1 VUE GÉNÉRALE 34 3.2 IMPACTS PAR TYPE DE SOUS-PROJET 34 3.3 ESTIMATION DE L’IMPACT 37 3.3.1 BESOINS EN TERRES 38 3.3.2 NOMBRE POSSIBLE DE PERSONNES CONCERNÉES 39 4. CONTEXTE JURIDIQUE ET INSTITUTIONNEL DU RECASEMENT 42 4. 1 CADRE JURIDIQUE NATIONAL 42 4. 1.1 LE RÉGIME DE L’OCCUPATION ET LE STATUT DES TERRES 42 4.1.1.1 Les différents titres portant sur la terre 42 4.1.1.2 La procédure de concession des terres rurales 44 4.1.1.3 Le statut des différentes terres 44 4.1.1.3.1 Les terres du domaine de l’Etat 44 2 4.1.1.3.2 Les terres des particuliers 44 4.1.1.3.3 Les terres des communautés locales 45 4.1.2 LES MÉCANISMES D’ATTEINTE À LA PROPRIÉTÉ 45 4. -

Rapportsituationdroitshumains Nordkivu

GROUPE D’ASSOCIATIONS DE DEFENSE DES DROITS DE L’HOMME ET DE LA PAIX Courriel : [email protected] Tel : +243999425284 RAPPORT ANNUEL SUR LA SITUATION GENERALE DES DROITS HUMAINS AU NORD KIVU, EN REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Janvier 2011 1 Motivation Le GADHOP est un réseau de 22 organisations de droits humains et de paix en République démocratique du Congo dont le rayon d’action statutaire est toute la RDC, mais dont les actions de terrain se font au Nord Kivu et surtout dans les deux Territoires de Beni et de Lubero. Existant depuis mars 2001, son siège social se trouve dans la ville de Butembo, a l’Avenue du Centre n0 40, dans la commune de Kimemi. Le présent rapport est une synthèse sur l’état de lieux des droits humains et de la paix au Nord Kivu pendant l’exercice 2010 car, dans la vision du GADHOP depuis sa création, ces deux domaines sont très liés. Nous faisons un commentaire relatant notre compréhension de la situation qui est suivi de nos recommandations à l’autorité provinciale et nationale pour l’amélioration de la situation au Nord Kivu. Nous mettons en annexe les tableaux des rapports mensuels sur les violations des droits humains et les événements de non paix comme les pillages, les vols mains armées, et autres. Ces derniers sont des faits dont on ne sait pas dire d’emblée qu’ils sont des violations des droits humains, sauf en cas de preuve d’indifférence de l’Etat congolais à éradiquer le phénomène (exemple de vols mains armés dirigés par des bandits. -

ISFD-NORD-KIVU.Pdf

BANQUE CENTRALE DU CONGO Direction de la Surveillance des Intermédiaires Financiers INSTITUTIONS DU SYSTÈME FINANCIER DECENTRALISE DE LA PROVINCE DU NORD KIVU N° DENOMINATION REGION RAYON D'ACTION ADRESSE PHYSIQUE 1 COOPECCO BENI Nord Kivu Beni 135, Avenue du Stade, Quartier Résidentiel, Commune Bugulu ,Ville de Beni 2 COOPECCO-OICHA Nord Kivu Oicha Oicha, Territoire de Beni 3 MECRE-BENI/COOPEC Nord Kivu Beni 92, Boulevard Nyamwisi, Ville de Beni 4 COODEFI/COOPEC Nord Kivu Butembo 14, Avenue Kinshasa , Commune de Mususa, Ville de Butembo 5 COOPEC LA SEMENCE Nord Kivu Butembo 5, Avenue Matokeo, Ville de Butembo 6 155, Avenue Mobutu, Quartier Buturande, Cité de Kiwanja, Territoire de COOPECCO/BUTURANDE Nord Kivu Buturande Rutshuru 7 COOPEC IMARA/GOMA Nord Kivu Goma Boulevard Kanyamuhanga , en face de ONC, Ville de Goma 8 COOPEC ADEC Nord Kivu Goma Avenue des Touristes, Quartier Mikeno, Maison Bercy Ville de Goma 9 COOPEC BONNE MOISSON Nord Kivu GOMA 12, Avenue Karisimbi, Quartier Mikeno, Commune de Goma, Ville de Goma 10 294, Avenue des Alizés , Quartier Murara, Commune Karisimbi, Ville de COOPEC KESHENI Nord Kivu Goma Goma 11 COOPEC TUJENGE PAMOJA Nord Kivu Goma 45, Boulevard Kayambayonga, Ville de Goma 12 COOPEC UMOJA NI NGUVU Nord Kivu GOMA 1, avenue Sake, Quartier Katoyi, Commune de Karisimbi, Ville de Goma 13 MECRE-BIRERE/COOPEC Nord Kivu Goma 11, Avenue du Commerce, Commune Karisimbi, Ville de Goma 14 MECREGO/COOPEC Nord Kivu Goma 30, Boulevard Kanyamuhanga, Quartier de Volcans, Ville de Goma 15 MECRE-KATINDO/COOPEC Nord Kivu Goma -

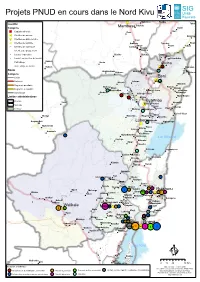

Projets PNUD En Cours Dans Le Nord Kivu

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SI! G !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Unité! ! ! ! ! Projets PN!UD en c! ours dans le Nord Kivu ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Pauvreté! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mabukulu Lol!wa! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ( ! ! ! ! ! Talolo ! Localité ! ! Tokoleko ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ma! mbasa Dandi ! ! ! Catégorie ! ! ! Bafwapoka ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! ! Capitale nationale ! Ofai ! ! ! !! /" ! ! Pede ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! /" ! Chef lieu de pr!ovince ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Buki!ringi ! ! !B!. afCwhefa liesu eden didstreict et ville ! ! ! ! ! Teturi ! (! ! ! ! ! ! !( Bigbulu Chef lieu de territoi!re A! malutu Tiperitsa !Boga ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sayo Dalia Tshabi ! !. Chef lieu de collectivité ! ! ! Lu!engb!a ! ! ! ! Butsha ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !( Butsha ! Chef lieu de groupement ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Localité importante Biasiko Biakatu Eringiti ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! Linzo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! !! !!! Localit!é ou chef lieu de localité ! ! ! ! ! ! Tchuchubo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Kakoro ! ! ! ! P! etit village ! Kenia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! O! icha ! ! ! !! ! Autre village ou localité ! ! ! ! ! ! Kakoro (! 1 Kamango ! ! Bakoroy! e ! ! Mbau ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bela ! ! ! ! !!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! !! Route ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! !! ! Abakuasimbo Mununzi 1 !!! ! ! !! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! Biabune ! ! ! ! !Kikura ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Home ! !!! ! ! Catégorie ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lo! cale ! ! ! Beni ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Nationale Lubena ! ! .!Muku1lia ! Mbunia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mwenda -

In Search of Peace: an Autopsy of the Political Dimensions of Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo

IN SEARCH OF PEACE: AN AUTOPSY OF THE POLITICAL DIMENSIONS OF VIOLENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO By AARON ZACHARIAH HALE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Aaron Zachariah Hale 2 To all the Congolese who helped me understand life’s difficult challenges, and to Fredline M’Cormack-Hale for your support and patience during this endeavor 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I was initially skeptical about attending The University of Florida (UF) in 2002 for a number of reasons, but attending UF has been one of the most memorable times of my life. I have been so fortunate to be given the opportunity to study African Politics in the Department of Political Science in a cozy little town like Gainesville. For students interested in Africa, UF’s Center for African Studies (CAS) has been such a fantastic resource and meeting place for all things African. Dr. Leonardo Villalón took over the management of CAS the same year and has led and expanded the CAS to reach beyond its traditional suit of Eastern and Southern African studies to now encompass much of the sub-region of West Africa. The CAS has grown leaps and bounds in recent years with recent faculty hires from many African and European countries to right here in the United States. In addition to a strong and committed body of faculty, I have seen in my stay of seven years the population of graduate and undergraduate students with an interest in Africa only swell, which bodes well for the upcoming generation of new Africanists. -

DRC INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) Annual Report - FY2020

DRC INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) Annual Report - FY2020 This publication was produced by the Integrated Governance Activity under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. Program Title: Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID DRC Contract Number: AID-660-C-17-00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: October 30, 2020 This publication was produced by the Integrated Governance Activity under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 ACTIVITY OVERVIEW/SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS 6 INTEGRATION OF CROSSCUTTING ISSUES AND USAID FORWARD PRIORITIES 33 GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT 33 YOUTH ENGAGEMENT 39 LOCAL CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT 41 SUSTAINABILITY 45 ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE 46 MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES 46 MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND LEARNING 48 INDICATORS 48 EVALUATION/ASSESSMENT STATUS AND/OR PLANS 59 CHALLENGES & LESSONS LEARNED 62 CHALLENGES 62 LESSONS LEARNED 62 ANNEXES 63 ANNEX A. COMMUNICATION AND OUTREACH MESSAGES 63 ANNEX B. -

North Kivu Field Office, Butembo, Democratic Republic of Congo

North Kivu Field office, Butembo, Democratic Republic of Congo. Photo courtesy of North East Congo Union Mission. North Kivu Field MUHINDO KYUSA Muhindo Kyusa The North Kivu Field (formerly known as North Kivu Association) is located in the eastern part of North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It occupies the two territories of Lubero and Beni. Its headquarters is in Kyaghala, Butembo City. A large part of the region is populated by the Nande tribe. The field has a common border to the east with Uganda, to the north with the province of Ituri, to the south with the territory of Rutshuru and to the west with the territory of Walikale. The territory of Lubero covers an area of 18,096 square kilometers and includes four communities (chiefdoms) while the territory of Beni covers an area of 7,484 square kilometers and also includes four communities (chiefdoms). There are two major cities in the region, Beni and Butembo. The average altitude of this region is around 1,500 meters but varies from 850 meters or a slope of 4,000 meters. The North Kivu Field was originally organized as the North Congo Field in 1954.1 It was known as the North Zaire Field from 1971 to 1995.2 From 1995 to 2018, it was known as the North Kivu Association.3 Demographics The population of the North Kivu Field is characterized by an attachment to the land. Ethnically, the population is homogeneous (especially in Lubero), made up predominantly of the Nande ethnic group. This homogeneity means that people know each other, sharing origins, social customs, professional memberships, religion, and networks which engender trust. -

République Démocratique Du Congo

f R é p u b l i q u e d é m o c r a t i q u e d u C o n g o - N o r d K i v u Ville de Butembo, 15 Octobre 2018 Village DJUGU WAMBA H A U T - U E L E DJUGU BUTUHE !\!(Bunia Irumu t r !\ e Mambasa b Bunia l !\ A e k I T U R I MAMBASA IRUMU a Bafwasende L Kasitu !\ Village KASITU Beni !\ BAFWASENDE Groupement de T S H O P O MALIO BUTE!\MBO OICHA LUBERO N N " " 0 0 ' ' 2 2 1 Lubero 1 ° ° 0 !\ 0 OUGANDA rd a w d E ke a L N O R D - K I V U LUBUTU RUTSHURU WALIKALE Rutshuru !\ TANZANIE Village VULINDI Walikale Masisi !\ !\ MASISI NYIRAGONGO GOMA !(GGomaoma PUNIA !\ M A N I E M A Idjwi RWANDA u !\ v i KALEHE Kalehe K !\ c S U D - K I V U a SHABUNDA IDJWI L KABARE E.P.Umoja Groupement de BUNYUKA Village MUTUNDU Village BULEGHA Quartier E.P.Vulindi E.P.Meso Village Mukalangirwa Maghombi Quartier VUHINGA Kamesi Mbonzo N N " Mama Musay Village " 0 0 ' ' 0 MUTANO 0 1 1 ° ° 0 0 Commune de VULAMBA Inst.Mihake Inst.Nuru Mama Rose Quartier Quartier E.P.Masoy Wayene Congo ya sika Makerere Village BUKOROGHOTO Disp. Gloria Quartier Muchanga E.P. Mavono Clin. Gloria Kalemire Inst.Lyambo Butembo Kivika UCG Inst.Buliki Paroisse Lyambo Groupement de Quartier ISALE-BULAMBO Quartier E.P.Mirembo E.P.Kitatumba Kimbulu Matembe Muyisa HGR de Kitatumba Paroisse Kitatumba Maison Kituli Inst.Butembo Le Roi Mairie de Butembo Quartier E.P.Kambali Kambali Inst.Kambali Clinique PÚdiatriq Quartier Mutiri Wanamahika Mukuna E.P.Kamusonge CHP Heshima Letu Marché central E.P.Masikilizano Quartier Quartier Commune de BULENGERA Ngere N De l'Evêché N " " 0 0 ' ' 8 8 ° E.P.A. -

Province Du Nord-Kivu Profil Resume Pauvrete

Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement Unité de lutte contre la pauvreté RDC PROVINCE DU NORD-KIVU PROFIL RESUME PAUVRETE ET CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES Mars 2009 Sommaire PROVINCE DU NORD-KIVU Avant-propos..............................................................3 Province Nord-Kivu 1 – La province du Nord-Kivu en un clin d’oeil...........4 Superficie 59.483 Km2 2 – La pauvreté au Nord-Kivu ....................................6 Population en 2005 4,5 millions 3 – L’éducation.........................................................10 Densité 75 hab/km² Nb de communes 7 4 – Le développement socio-économique des Nb de quartiers 37 femmes.....................................................................11 Routes urbaines 5109 km 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............11 Routes nationales 2.134 km 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............12 Routes d’intérêt provincial 20371 km 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Réseau ferroviaire 0 km 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Gestion de la province Gouvernement 7 – Le sida et le paludisme ......................................14 Provincial 8 – L’habitat, l’eau et l’assainissement ....................15 Nb de ministres provinciaux 10 9 – Le développement communautaire et l’appui des Nb de députés provinciaux 42 Partenaires Techniques et Financiers (PTF) ...........16 - 2 – PROVINCE DU NORD KIVU Avant-propos Le présent rapport est une analyse succincte des conditions -

Republique Democratique Du Congo Ministere Des

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO MINISTERE DES FINANCES DIRECTION GENERALE DES IMPÔTS DIRECTION DE L'ASSIETTE FISCALE REPERTOIRE DES CONTRIBUABLES ASSUJETTIS A LA TVA , ARRETE AU 28 FEVRIER 2018 FORME SERVICE N° NIF JURIDIQUE NOMS OU RAISON SOCIALE SIGLE ADRESSE SECTEUR D'ACTIVITE ETAT SOCIETE GESTIONNAIRE 1 A1102780K PM ABATTOIR DE GOMA SABAGO C/ GOMA Q/ KYESHERO AV. KITUKO Autres EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Commerce Général et Import- 2 A1113520J PP ABBAS SALEH IBRAHIM ETS SOZANG C/ GOMA Q/ MURARA AV. DU COMMERCE Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Commerce Général et Import- EN CESSATION 3 A1311360N PP ABDALLAH HIJAZI PAIN ROYAL C/DE GOMA Q/ LES VOLCANS AV. DES ECOLES Export D'ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA EST MIS MAX C/ DE GOMA Q/LES VOLCANS Commerce Général et Import- 4 A1105551X PP ABDUL RAZACK MOIDEEN DIGITAL BLVD.KANYAMUHANGA Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Ets BON Commerce Général et Import- 5 A1001421G PP ABOUBAKAR SADI SADI VOYAGE' C/GOMA Q/KATINDO AV. ROUTE SAKE Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Commerce Général et Import- 6 A1509793M PM AFRICA CLEANING PRODUCTS COMPANY ACPC AV. CORNICHE N° 21 Q. VOLCANS COMM. DE GOMA Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Entreprises minières et 7 A1507484C PM AFRICA SHINING STONE A.S.STO SARL AV PELICAN Q/DES VOLCANS C/GOMA pétrolières EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA 8 A1302749D PM AFRICA SMILTING GROUPE CITE DE SAKE TERRITOIRE DE MASISI NORD - KIVU Industie EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA Prestation de services et 9 A1601874F PM AFRICAN BUILDERS CONGO ABC AV. DU LAC N° 18 Q/ HIMBI C/GOMA travaux immobiliers EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA AV.BLVD KANYAMUHANGA ROND POINT SIGNERS 10 A1406965M PM AFRICAN DRILLING LIMITED C/GOMA V/GOMA P/NORD-KIVU Industie EN ACTIVITE CDI / GOMA AV.