Dancing Mania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song

Lyric Possession: A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Smith, Dori Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 04:42:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/560813 LYRIC POSSESSION : A DRAMATIZATION OF ITALIAN TARANTISM IN SONG by Dori Marie Smith __________________________ Copyright © Dori Marie Smith 2015 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Dori Marie Smith, titled Lyric Possession: A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 Kristin Dauphinais _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 David Ward _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 William Andrew Stuckey _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24. 2015 Janet Sturman Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Trance As Artefact: De-Othering Transformative States with Reference to Examples from Contemporary Dance in Canada

Trance as Artefact: De-Othering transformative states with reference to examples from contemporary dance in Canada Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Dance Studies, University of Surrey August 1st, 2007 Bridget E. Cauthery © by Bridget E. Cauthery (2007) ABSTRACT Reflecting on his fieldwork among the Malagasy speakers of Mayotte in the Indian Ocean, Canadian anthropologist Michael Lambek questions why the West has a “blind spot” when it comes to the human activity of trance. Immersed in his subject’s trance practices, he questions why such a fundamental aspect of the Malagasy culture, and many other cultures he has studied around the world, is absent from his own. This research addresses the West’s preoccupation with trance in ethnographic research and simultaneous disinclination to attribute or situate trance within its own indigenous dance practices. From a Western perspective, the practice and application of research suggests a paradigm that locates trance according to an imperialist West/non-West agenda. If the accumulated knowledge and data about trance is a by-product of the colonialist project, then trance may be perceived as an attribute or characteristic of the Other. As a means of investigating this imbalance, I propose that trance could be reconceived as an attribute or characteristic of the Self, as exemplified by dancers engaged in Western dance practices within traditional anthropology’s “own backyard.” In doing so, I examine the degree to which trance can be a meaningful construct within the cultural analysis of contemporary dance creation and performance. Through case studies with four dancer/choreographers active in Canada, Margie Gillis, Zab Maboungou, Brian Webb and Vincent Sekwati Mantsoe, this research explores the cultural parameters and framing of transformative states in contemporary dance. -

From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania As Cultural Symptom

270 Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(2), pp 270–276 April 2021 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/pli.2020.46 From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania as Cultural Symptom Ananya Jahanara Kabir Keywords: choreomania, imperial medievalism, Dionysian revivals, St. John’s dances, kola sanjon Paris in the interwar years was abuzz with Black dance and dancers. The stage was set since the First World War, when expatriate African Americans first began creating here, through their performance and patronage of jazz, “a new sense of black commu- nity, one based on positive affects and experience.”1 This community was a permeable one, where men and women of different races came together on the dance floor. As the novelist Michel Leiris recalls in his autobiographical work, L’Age d’homme, “During the years immediately following November 11th, 1918, nationalities were sufficiently con- fused and class barriers sufficiently lowered … for most parties given by young people to be strange mixtures where scions of the best families mixed with the dregs of the dance halls … In the period of great licence following the hostilities, jazz was a sign of allegiance, an orgiastic tribute to the colours of the moment. It functioned magically, and its means of influence can be compared to a kind of possession. -

The Taranta–Dance Ofthesacredspider

Annunziata Dellisanti THE TARANTA–DANCE OFTHESACREDSPIDER TARANTISM Tarantism is a widespread historical-religious phenomenon (‘rural’ according to De Martino) in Spain, Campania, Sardinia, Calabria and Puglia. It’s different forms shared an identical curative aim and by around the middle of the 19th century it had already begun to decline. Ever since the Middle Ages it had been thought that the victim of the bite of the tarantula (a large, non- poisonous spider) would be afflicted by an ailment with symptoms similar to those of epilepsy or hysteria. This ‘bite’ was also described as a mental disorder usually appearing at puberty, at the time of the summer solstice, and caused by the repression of physical desire, depression or unrequited love. In order to be freed from this illness, a particular ritual which included dance, music and the use of certain colours was performed. RITUAL DANCING The first written account of music as an antidote to the bite of the tarantula was given by the Jesuit scientist, Athanasius Kircher, who was also the first to notate the music and rhythm in his book Antidotum Tarantulæ in the 16th century. Among the instruments involved and used, the frame drum plays an important role together with the violin, the guitar or chitarra battente, a ten-string guitar used percussively, and the button accordion or organetto. This form of exorcism consisted in a ritual carried out in the home of the sick person and a religious ritual in the Church of San Paolo (Saint Paolo in Galatina (Lecce)) during the celebrations of the Saints Peter and Paul on the 28th June each year. -

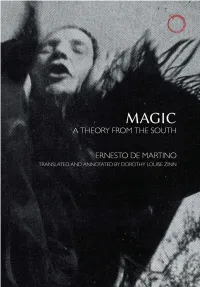

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Tarantism and Tarantella in a Doll's House

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives SANDRA COLELLA TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE MASTER THESIS IBSEN STUDIES 2007 INDEX INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………pg 3 CHAPTER 1 TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE . IBSENIAN SCHOLARS’ VIEWS..........………………………………………………...…...pg 15 CHAPTER 2 TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA. BERGSØE’S TREATISE AND THE SCANDINAVIAN STUDIES…………………………………………………….pg 31 CHAPTER 3 THE ITALIAN FOLK DANCE TARANTELLA………………………………………..….pg 45 CHAPTER 4 THE PHENOMENON OF TARANTISM. DE MARTINO’S WORKS AND THE OTHER STUDIES……………………………………………………………..…pg 55 CHAPTER 5 TARANTISM AND TARANTELLA IN A DOLL’S HOUSE . A NEW HYPOTHESIS OF INTERPRETATION……………………………………….…pg 85 CONCLUSION...………………………………………………………………………………pg 99 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………....…pg 101 2 INTRODUCTION Echoes of the controversies about the meaning of the drama A Doll’s House and Nora’s character continue to reach us from 1879, the year in which Ibsen completed his probably most famous work in Amalfi. Up till now, the complexity of the characters and the wise webbing of the drama, scattered of symbolic moments, widening its study, are the cause of divergent interpretations by the scholars. An example, exemplifying for all the discussions, could be the famous problem of Ibsen’s “feminism”. In the chapter “The poetry of feminism” in her book Ibsen’s women the American scholar Joan Templeton (2001) tries to say a definitive word about the sense to attribute to the drama. She quotes an impressive series of evidences with great accuracy, coming not only from works, but also from specific events and stands of which Ibsen was protagonist, to be opposed to only one point in favour of the detractors of the feminist vision about A Doll’s House . -

Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance In

DANCING IN BODY AND SPIRIT: DANCE AND SACRED PERFORMANCE IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY BEGUINE TEXTS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Jessica Van Oort May, 2009 ii DEDICATION To my mother, Valerie Van Oort (1951-2007), who played the flute in church while I danced as a child. I know that she still sees me dance, and I am sure that she is proud. iii ABSTRACT Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance in Thirteenth-Century Beguine Texts Candidate’s Name: Jessica Van Oort Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Joellen Meglin This study examines dance and dance-like sacred performance in four texts by or about the thirteenth-century beguines Elisabeth of Spalbeek, Hadewijch, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Agnes Blannbekin. These women wrote about dance as a visionary experience of the joys of heaven or the relationship between God and the soul, and they also created physical performances of faith that, while not called dance by medieval authors, seem remarkably dance- like to a modern eye. The existence of these dance-like sacred performances calls into question the commonly-held belief that most medieval Christians denied their bodies in favor of their souls and considered dancing sinful. In contrast to official church prohibitions of dance I present an alternative viewpoint, that of religious Christian women who physically performed their faith. The research questions this study addresses include the following: what meanings did the concept of dance have for medieval Christians; how did both actual physical dances and the concept of dance relate to sacred performance; and which aspects of certain medieval dances and performances made them sacred to those who performed and those who observed? In a historical interplay of text and context, I thematically analyze four beguine texts and situate them within the larger tapestry of medieval dance and sacred performance. -

Tarantism.Pdf

Medical History, 1979, 23: 404-425. TARANTISM by JEAN FOGO RUSSELL* INTRODUCTION TARANTISM IS A disorder characterized by dancing which classically follows the bite of a spider and is cured by music. It may involve one or many persons, and was first described in the eleventh century, but during the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries many outbreaks were observed and recorded, notably in southern Italy. There is no doubt that it is a hysterical phenomenon closely related to the dancing mania which occurred in Europe in the Middle Ages and with which it is often confused, but unlike the dancing mania it is initiated by a specific cause, real or imagined, and occurs during the summer when the spiders are about. Music as a cure for tarantism was first used in Apulia, a southern state of Italy, where the folk dances would seem to have developed. The music used in the cure is a quick, lively, uninterrupted tune with short repetitive phrases played with increasing tempo and called a tarantella. The word "tarantella" has two meanings: the first is the name of the tune and the second is the name of the accompanying dance which is defined as: "A rapid, whirling southern Italian dance popular with the peasantry since the fifteenth century when it was supposed to be the sovereign remedy for tarantism".11 The dance form still exists, as Raffe2 points out: "The Tarantella is danced in Sicily on every possible occasion, to accompaniment of hand clapping, couples improvising their own figures. It is found in Capri and Sorrento, and in Apulia it is known as the Taranda. -

Gender and Dance in Modern Iran 1St Edition Ebook Free

GENDER AND DANCE IN MODERN IRAN 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ida Meftahi | 9781317620624 | | | | | Gender and Dance in Modern Iran 1st edition PDF Book Burchell, C. The John F. Retrieved September 6, Like other sectors of society during Reza Shah's rule, however, women lost the right to express themselves and dissent was repressed. In , the ban on women was extended to volleyball. Mediterranean delight festival. During the rule of Mohammad Khatami , Iran's president between and , educational opportunities for women grew. The Telegraph. Women have been banned from Tehran's Azadi soccer stadium since Khomeini led protests about women's voting rights that resulted in the repeal of the law. A general trend in these writings has been to link the genealogy of whirling dervish ceremonies—which are performed in Turkey today by Mevlevi-order dervishes— to Iranian mysticism described in Persian poetry. Neil Siegel. Figure 1. It ana- lyzes the ways in which dancing bodies have provided evidence for competing representations of modernity, urbanity, and Islam throughout the twentieth century. Because the first Pahlavi Shah banned the use of the hijab, many women decided to show their favor of Khomeini by wearing a chador, thinking this would be the best way to show their support without being vocal. Retrieved March 12, Archived from the original on February 23, Anthony Shay and Barbara. Genres of dance in Iran vary depending on the area, culture, and language of the local people, and can range from sophisticated reconstructions of refined court dances to energetic folk dances. Khamenei called for a ban on vasectomies and tubal ligation in an effort to increase population growth. -

Workshop Ceremony Dance Film Food & Drink Iranian Bazaar Kids Music Talk / Presentation Theatre Tribute Visual Arts

Date Start End Event Location Ceremony Aug 20,2015 8:30 PM 9:00 PM Opening Speeches Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 12:00 PM 1:00 PM Short Story and Photo Contest Award Ceremony Studio Theatre Aug 23,2015 4:30 PM 5:45 PM Closing Ceremony (Volunteers and Artists Appreciation - Part I) Westjet Stage Dance Aug 22,2015 12:15 PM 12:45 PM Azarbaijani Dance (Tabriz Dance Group) Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 1:30 PM 2:00 PM Kurdish Dance (Mayn Zard Dance Group) Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 3:00 PM 4:00 PM Iranian Traditional and Folk Dances - Vancouver Pars National Ballet Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 6:30 PM 7:00 PM Azarbaijani Dance (Tabriz Dance Group) Stage in Round Aug 22,2015 8:00 PM 9:30 PM Les Ballets Persans (Iranian Ballet)* Fleck Dance Theatre Aug 23,2015 1:00 PM 2:30 PM Les Ballets Persans (Iranian Ballet)* Fleck Dance Theatre Aug 23,2015 1:00 PM 2:00 PM Iranian Traditional and Folk Dances - Vancouver Pars National Ballet Westjet Stage Aug 23,2015 4:00 PM 4:30 PM Kurdish Dance (Mayn Zard Dance Group) East Side Stage Film Aug 21,2015 7:00 PM 8:45 PM Window Horses Animated Feature Film + Panel Discussion Studio Theatre Aug 21,2015 9:30 PM 11:30 PM Abbas Kiarostami: A Report + Q&A (Directed by Bahman Maghsoudlou) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 10:00 AM 11:30 AM Residents of One Way Street (Directed by Mahdi Bagheri) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 1:30 PM 3:15 PM One.Two.One + Q&A (Directed by Mania Akbari) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Exilic Trilogy + Q&A and Panel Discussion (Directed by Arsalan Baraheni) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 6:45 PM 8:45 -

The Modern Dance

Library of Congress The modern dance; a historical and analytical treatment of the subject; religious, social, hygienic, industrial aspects as viewed by the pulpit, the press, medical authorities, municipal authorities, social workers, etc., by M. F. Ham ... illustrations by Will N. Nooman. LIGHT ON THE DANCE by M. F. HAM EVANGELIST. The Modern Dance A Historical and Analytical Treatment of the Subject Religious, Social, Hygienic, Industrial Aspects As viewed by The Pulpit, the Press, Medical Authorities, Municipal Authorities, Social Workers, etc. By M ordecai . F ranklin . HAM, Evangelist Illustrations by Will N. Noonan SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Copyright applied for GV1741 .H3 EVANGELIST M. F. HAM The modern dance; a historical and analytical treatment of the subject; religious, social, hygienic, industrial aspects as viewed by the pulpit, the press, medical authorities, municipal authorities, social workers, etc., by M. F. Ham ... illustrations by Will N. Nooman. http:// www.loc.gov/resource/musdi.207 Library of Congress $0 15 ©CI.A431552 JUN 19 1916 no. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFATORY NOTE 3 INTRODUCTORY A Plea For An Open Mind 7 CHAPTER I Popular Ignorance Cleared Away 7 CHAPTER II Brief History of the Dance Dance of Rejoicing. Bible Dance. Modern Dance. 10 CHAPTER III Many Witnesses Testify The Church. Great Preachers. Foremost Men. Dancer and Dancing Master. Municipal Authorities. The Press. Physicians. Business Men. Soul Winners. Hospital and Social Welfare Workers. 13 CHAPTER IV A Country Wide Menace Evidence from Oklahoma. Evidence from Chicago. Evidence from San Francisco. Evidence from Kansas City. Sins of the Fathers. 29 CHAPTER V Psychology of the Dance Craze 35 CHAPTER VI Excuses to Justify the Dance Necessary Amusement. -

'Tradizione E Contaminazione': an Ethnography of The

‘TRADIZIONE E CONTAMINAZIONE’: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE CONTEMPORARY SOUTHERN ITALIAN FOLK REVIVAL Stephen Francis William Bennetts BA (Hons), Australian National University, 1987 MA, Sydney University, 1993 Graduate Diploma (Communication), University of Technology, Sydney, 1999 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia, School of Social Sciences, Discipline of Anthropology and Sociology 2012 ‘Pizzicarello’, Tessa Joy, 2010. 1 2 I have acquired the taste For this astringent knowledge Distilled through the Stringent application of the scientific method, The dry martini of the Intellectual world, Shaken, not stirred. But does this mean I must eschew Other truths? From ‘The Bats of Wombat State Forest’ in Wild Familiars (2006) by Liana Christensen 3 4 ABSTRACT The revival since the early 1990s of Southern Italian folk traditions has seen the ‘rediscovery’ and active recuperation, especially by urban revivalist actors, of le tradizioni popolari, popular traditional practices originating in peasant society which are still practiced by some traditional local actors in remote rural areas of Southern Italy. This thesis draws on interviews, participant observation and historical research carried out mainly during fieldwork in Rome and Southern Italy in 2002-3 to present an ethnography of the urban revivalist subculture which has been the main driving force behind the contemporary Southern Italian folk revival. In the course of my enquiry into why the movement has emerged, I combine both synchronic and diachronic perspectives, as well as a phenomenological analysis of revivalist motivation and agency, to explore the question of why contemporary urban revivalists have begun to take an interest in the archaic and marginalised cultural practices of rural Southern Italy.