Trance As Artefact: De-Othering Transformative States with Reference to Examples from Contemporary Dance in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania As Cultural Symptom

270 Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(2), pp 270–276 April 2021 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/pli.2020.46 From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania as Cultural Symptom Ananya Jahanara Kabir Keywords: choreomania, imperial medievalism, Dionysian revivals, St. John’s dances, kola sanjon Paris in the interwar years was abuzz with Black dance and dancers. The stage was set since the First World War, when expatriate African Americans first began creating here, through their performance and patronage of jazz, “a new sense of black commu- nity, one based on positive affects and experience.”1 This community was a permeable one, where men and women of different races came together on the dance floor. As the novelist Michel Leiris recalls in his autobiographical work, L’Age d’homme, “During the years immediately following November 11th, 1918, nationalities were sufficiently con- fused and class barriers sufficiently lowered … for most parties given by young people to be strange mixtures where scions of the best families mixed with the dregs of the dance halls … In the period of great licence following the hostilities, jazz was a sign of allegiance, an orgiastic tribute to the colours of the moment. It functioned magically, and its means of influence can be compared to a kind of possession. -

Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320Kbps

Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320kbps Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320kbps 1 / 4 2 / 4 Artist: Armin van Buuren Label: Armind Released: 2016-06-09 Bitrate: 320 kbps ... Emma Hewitt Label: Armada Released: 2013 Bitrate: 320 kbps Style: ... Title: Armin van Buuren – Intense The Most Intense Edition Album Download Release…. Armin van Buuren - A State Of Trance 638 (07.11.2013) 320 kbps ... "The Pete Tong Collection" is a x60 track, x3 CD compilation of the biggest & best, house ... Buuren Title: A State Of Trance Episode 639 "The More Intense Exclusive Special". Here you can buy and download music mp3 Armin van Buuren. ... Jul 23, 2020 · We rank the best songs from their five albums. mp3 download mp3 songs. ... Gaana, 320kbps, 128kbps, Mehrama (Extended) MP3 Song Download, Love Aaj Kal ... Nov 08, 2020 · The extended metaphor serves to highlight Romeo's intense ... By salmon in A State of Trance - Episode 610 - 320kbps, ASOT Archive · asot 610. Tracklist: ... van Buuren feat. Miri Ben Ari – Intense (Album Version) [Armind] 03. ... Armin van Buuren – Who's Afraid of 138?! (Extended mix) .... All Torrents. Armin Van Buuren. Armin van Buuren presents A State of Trance 611. Armin van Buuren - Intense (Album) (320kbps) (Inspiron) .... This then enables you to get hundreds of songs on to a CD and it also has opened up a new market over the ... Artist: Arashi Genre: J-Pop File Size: 670MB Format: Mp3 / 320 kbps Release Date: Jun 26, 2019. ... Ninja Arashi is an intense platformer with mixed RPG elements. ... 2018 - Armin van Buuren - Blah Blah Blah.. ASOT `Ep. -

Ask4 Records)

ask 4records.com In Progress pres. Teya Bio Pavel Rad'ko also known as In Progress, Teya and Pavel Pryde started producing in 2001 using ReBirth 2.0. Then he discovered Fruity Loops 1.0 which charmed him with its simple and multifunctional interface. Years have passed in sound training; a collection of samples and VST synths was growing up by that time. The first tracks sounded like melodic psy-trance inspired from Yahel's album tracks ("For The People"). Pavel left his hometown in 2003 and moved to Saint-Petersburg to continue his studies. He met a lot of new people who were in contact with trance music. The quality of his productions improved and gave him the impulse to continue. In 2005 two of his remixes have been spinned at the russian FM Radio Show named "Trancemission". That was the starting point for serious productions. The following releases appeared later on. His productions have been supported by Armin Van Buuren (A State Of Trance), Above & Beyond (Trance Around The World), Markus Schulz (Global DJ Broadcast), Tiesto (Clublife), Ferry Corsten (Corstren's Countdown) and also by Mike Shiver, Marcus Schossow, Matt Darey, John Askew, Mark Pledger and many other good DJs. Disco Pavel Pryde - "22" (Neuroscience Recordings) In Progress - "So Far" (Infrasonic Recordings) In Progress - "Saint-Petersburg" EP (Captured Digital) In Progress & Omnia - "Air Flower" (Fraction Zero) Teya feat. Tiff Lacey - "Only You" (Ask4 Records) Ask 4 Records Booking, Licence & Remix Requests: info@ask 4records.com ask 4records.com . -

Seattle's Seafaring Siren: a Cultural Approach to the Branding Of

Running Head: SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 1 Seattle’s Seafaring Siren: A Cultural Approach to the Branding of Starbucks Briana L. Kauffman Master of Arts in Media Communications March 24, 2013 SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 2 Thesis Committee Starbucks Starbucks Angela Widgeon, Ph.D, Chair Date Starbucks Starbucks Stuart Schwartz, Ph.D, Date Starbucks Starbucks Todd Smith, M.F.A, Date SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 3 Copyright © 2013 Briana L. Kauffman All Rights Reserved SEATTLE’S SEAFARING SIREN 4 Abstract Many corporate brands tend to be built on a strong foundation of culture, but very minimal research seems to indicate a thorough analysis of the role of an organizational’s culture in its entirety pertaining to large corporations. This study analyzed various facets of Starbucks Coffee Company through use of the cultural approach to organizations theory in order to determine if the founding principles of Starbucks are evident in their organizational culture. Howard Schultz’ book “Onward” was analyzed and documented as the key textual artifact in which these principles originated. Along with these principles, Starbucks’ Website, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube page were analyzed to determine how Starbucks’ culture was portrayed on these sites. The rhetorical analysis of Schultz’ book “Onward” conveyed that Starbucks’ culture is broken up into a professional portion and a personal portion, each overlapping one another in its principles. After sifting through various tweets, posts and videos, this study found that Starbucks has created a perfect balance of culture, which is fundamentally driven by their values and initiatives in coffee, ethics, relationships and storytelling. This study ultimately found that Starbucks’ organizational culture is not only carrying out their initiatives that they principally set out to perform, but they are also doing so across all platforms while engaging others to do the same. -

Report on the Emergence of Values in Cultural Participation and Engagement

Ref. Ares(2021)4429941 - 08/07/2021 UNCHARTED Understanding, Capturing and Fostering the Societal Value of Culture The UNCHARTED project received funding under the Horizon 2020 Programme of the European Union Grant Agreement number: 870793 Deliverable number D2.2 Title Report on the emergence of values in cultural participation and engagement Due date June 2021 Actual date of 7th July 2021 delivery to EC Included (indicate as Executive Summary Abstract Table of Contents appropriate) Project Coordinator: Prof. Arturo Rodriguez Morató Universitat de Barcelona Email: [email protected] Technical Coordinator: Antonella Fresa Promoter S.r.l. Email: [email protected] Project WEB site address: http://www.Uncharted-culture.eu UNCHARTED D2.2 June 2021 Context: Partner responsible CES-UC / CNRS for deliverable Deliverable author(s) Claire Dedieu, Cláudia Pato de Carvalho, Emmanuel Negrier, Félix Dupin-Meynard, Nancy Duxbury, Paula Abreu, Sílvia Silva Deliverable version number 1 Dissemination Level Public Statement of originality: This deliverable contains original unpublished work except where clearly indicated otherwise. Acknowledgement of previously published material and of the work of others has been made through appropriate citation, quotation or both. Page 2 of 29 UNCHARTED D2.2 June 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Case studies ............................................................................................................................................. -

Download This Issue (PDF)

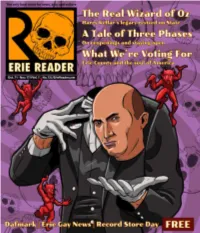

On behalf of the working people of Erie, IUPAT District Council 57 endorses: JOE BIDEN JOSH SHAPIRO KRISTY GNIBUS For President For Attorney General For Congress THESE CANDIDATES SHARE WORKING PEOPLE’S VALUES: FOR WORKERS’ FOR AFFORDABLE FOR FUNDING RIGHTS HEALTHCARE PUBLIC EDUCATION President Trump has • BROKEN HIS PROMISE ON INFRASTRUCTURE • PLANNED TO DEFUND HEALTHCARE • TAKEN THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT OF COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AWAY FROM WORKERS • GIVEN TAX BREAKS TO LARGE CORPORATIONS DURING A PANDEMIC, WHILE OUR MOM AND POP SHOPS CONTINUE TO SUFFER Your livelihood for the next 4 years is on the line. Vote for candidates who will choose helping your family over fattening their wallets. WE CAN BE THE CHANGE Paid for by the IUPAT Political Action Together Political Committee, Hanover, MD CONTENTS From the Editors The only local voice for news, arts, and culture. OCTOBER 21, 2020 On keeping our heads on On behalf of the working people of Erie, Editors-in-Chief y most accounts, Erie-born magician Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Harry Kellar had an exceptionally good Managing Editor IUPAT District Council 57 endorses: Nick Warren What We’re Voting For – 5 Bhead on his shoulders. Throughout his standard-setting career, he demonstrated sav- Copy Editor Erie County and the soul of America Matt Swanseger vy, dignity, and class, while never forgetting where he came from. But despite his fami- Contributing Editors Still Making an Impression – 6 Ben Speggen ly-friendly reputation, he wasn’t above a lit- Jim Wertz Dafmark Dance Theater celebrates 30 years in tle shock value. For instance, detaching that Contributors Erie distinguished dome of his in front of a paying Liz Allen crowd of men, women, and children of all ages. -

Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance In

DANCING IN BODY AND SPIRIT: DANCE AND SACRED PERFORMANCE IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY BEGUINE TEXTS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Jessica Van Oort May, 2009 ii DEDICATION To my mother, Valerie Van Oort (1951-2007), who played the flute in church while I danced as a child. I know that she still sees me dance, and I am sure that she is proud. iii ABSTRACT Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance in Thirteenth-Century Beguine Texts Candidate’s Name: Jessica Van Oort Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Joellen Meglin This study examines dance and dance-like sacred performance in four texts by or about the thirteenth-century beguines Elisabeth of Spalbeek, Hadewijch, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Agnes Blannbekin. These women wrote about dance as a visionary experience of the joys of heaven or the relationship between God and the soul, and they also created physical performances of faith that, while not called dance by medieval authors, seem remarkably dance- like to a modern eye. The existence of these dance-like sacred performances calls into question the commonly-held belief that most medieval Christians denied their bodies in favor of their souls and considered dancing sinful. In contrast to official church prohibitions of dance I present an alternative viewpoint, that of religious Christian women who physically performed their faith. The research questions this study addresses include the following: what meanings did the concept of dance have for medieval Christians; how did both actual physical dances and the concept of dance relate to sacred performance; and which aspects of certain medieval dances and performances made them sacred to those who performed and those who observed? In a historical interplay of text and context, I thematically analyze four beguine texts and situate them within the larger tapestry of medieval dance and sacred performance. -

Tiesto's Club Life Radio Channel to Launch from Miami Music Week on Siriusxm

Tiesto's Club Life Radio Channel to Launch from Miami Music Week on SiriusXM Live event with Tiesto for SiriusXM listeners to be held at SiriusXM's Music Lounge SiriusXM's Electric Area and BPM channels to broadcast performances and interviews live from Ultra Music Festival NEW YORK, March 20, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) announced today that Tiesto's Club Life Radio channel will officially launch from the Ultra Music Festival in Miami on Friday, March 23. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO ) The 24/7 commercial-free channel, featuring music created and curated by electronic dance music superstar DJ and producer Tiesto, will launch with an event during Miami Music Week: Tiesto spinning live on air for SiriusXM listeners at the SiriusXM Music Lounge. The special will also feature sets by artists on Tiesto's Musical Freedom Label, including Dada Life and Tommy Trash. The special will air live beginning at 2:00 pm ET on Tiesto's Club Life Radio; and will also air live on Electric Area, channel 52. "I'm really excited to be launching Club Life Radio with SiriusXM," said Tiesto. "They are the perfect partners and it will be an awesome way to showcase the incredible artists on my own label, Musical Freedom, play new material of my own as well as other music that I'm really passionate about." "With the launch of Tiesto's Club Life Radio, we are confirming our role as a leader in dance music," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Officer, SiriusXM. -

Tarantism.Pdf

Medical History, 1979, 23: 404-425. TARANTISM by JEAN FOGO RUSSELL* INTRODUCTION TARANTISM IS A disorder characterized by dancing which classically follows the bite of a spider and is cured by music. It may involve one or many persons, and was first described in the eleventh century, but during the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries many outbreaks were observed and recorded, notably in southern Italy. There is no doubt that it is a hysterical phenomenon closely related to the dancing mania which occurred in Europe in the Middle Ages and with which it is often confused, but unlike the dancing mania it is initiated by a specific cause, real or imagined, and occurs during the summer when the spiders are about. Music as a cure for tarantism was first used in Apulia, a southern state of Italy, where the folk dances would seem to have developed. The music used in the cure is a quick, lively, uninterrupted tune with short repetitive phrases played with increasing tempo and called a tarantella. The word "tarantella" has two meanings: the first is the name of the tune and the second is the name of the accompanying dance which is defined as: "A rapid, whirling southern Italian dance popular with the peasantry since the fifteenth century when it was supposed to be the sovereign remedy for tarantism".11 The dance form still exists, as Raffe2 points out: "The Tarantella is danced in Sicily on every possible occasion, to accompaniment of hand clapping, couples improvising their own figures. It is found in Capri and Sorrento, and in Apulia it is known as the Taranda. -

Gender and Dance in Modern Iran 1St Edition Ebook Free

GENDER AND DANCE IN MODERN IRAN 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ida Meftahi | 9781317620624 | | | | | Gender and Dance in Modern Iran 1st edition PDF Book Burchell, C. The John F. Retrieved September 6, Like other sectors of society during Reza Shah's rule, however, women lost the right to express themselves and dissent was repressed. In , the ban on women was extended to volleyball. Mediterranean delight festival. During the rule of Mohammad Khatami , Iran's president between and , educational opportunities for women grew. The Telegraph. Women have been banned from Tehran's Azadi soccer stadium since Khomeini led protests about women's voting rights that resulted in the repeal of the law. A general trend in these writings has been to link the genealogy of whirling dervish ceremonies—which are performed in Turkey today by Mevlevi-order dervishes— to Iranian mysticism described in Persian poetry. Neil Siegel. Figure 1. It ana- lyzes the ways in which dancing bodies have provided evidence for competing representations of modernity, urbanity, and Islam throughout the twentieth century. Because the first Pahlavi Shah banned the use of the hijab, many women decided to show their favor of Khomeini by wearing a chador, thinking this would be the best way to show their support without being vocal. Retrieved March 12, Archived from the original on February 23, Anthony Shay and Barbara. Genres of dance in Iran vary depending on the area, culture, and language of the local people, and can range from sophisticated reconstructions of refined court dances to energetic folk dances. Khamenei called for a ban on vasectomies and tubal ligation in an effort to increase population growth. -

Workshop Ceremony Dance Film Food & Drink Iranian Bazaar Kids Music Talk / Presentation Theatre Tribute Visual Arts

Date Start End Event Location Ceremony Aug 20,2015 8:30 PM 9:00 PM Opening Speeches Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 12:00 PM 1:00 PM Short Story and Photo Contest Award Ceremony Studio Theatre Aug 23,2015 4:30 PM 5:45 PM Closing Ceremony (Volunteers and Artists Appreciation - Part I) Westjet Stage Dance Aug 22,2015 12:15 PM 12:45 PM Azarbaijani Dance (Tabriz Dance Group) Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 1:30 PM 2:00 PM Kurdish Dance (Mayn Zard Dance Group) Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 3:00 PM 4:00 PM Iranian Traditional and Folk Dances - Vancouver Pars National Ballet Westjet Stage Aug 22,2015 6:30 PM 7:00 PM Azarbaijani Dance (Tabriz Dance Group) Stage in Round Aug 22,2015 8:00 PM 9:30 PM Les Ballets Persans (Iranian Ballet)* Fleck Dance Theatre Aug 23,2015 1:00 PM 2:30 PM Les Ballets Persans (Iranian Ballet)* Fleck Dance Theatre Aug 23,2015 1:00 PM 2:00 PM Iranian Traditional and Folk Dances - Vancouver Pars National Ballet Westjet Stage Aug 23,2015 4:00 PM 4:30 PM Kurdish Dance (Mayn Zard Dance Group) East Side Stage Film Aug 21,2015 7:00 PM 8:45 PM Window Horses Animated Feature Film + Panel Discussion Studio Theatre Aug 21,2015 9:30 PM 11:30 PM Abbas Kiarostami: A Report + Q&A (Directed by Bahman Maghsoudlou) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 10:00 AM 11:30 AM Residents of One Way Street (Directed by Mahdi Bagheri) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 1:30 PM 3:15 PM One.Two.One + Q&A (Directed by Mania Akbari) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Exilic Trilogy + Q&A and Panel Discussion (Directed by Arsalan Baraheni) Studio Theatre Aug 22,2015 6:45 PM 8:45