Damascus.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

Kay 492 Turkish Administrative History Week 5: Seljuk Empire + Emergence of Turks in World History Ortaylı, Pp

Kay 492 Turkish Administrative History Week 5: Seljuk Empire + Emergence of Turks in World History Ortaylı, pp. 97-110 Emergence of Turks in History • Pre-Islamic Turkish tribes were influential • in Central Asia and Maveraünnehir (between Amudarya/ Seyhun and Syrderya/Ceyhun rivers), Caucasus, near Volga river and Near East • The Turks began to accept Islam from the 10th century and became an important force in the history of the Middle East • The mission of "being the sword of Islam" The Islamic World before the Seljuks • At the end of the 9th Century, Muslims dominated the Mediterranean • By the same time, the Eastern Roman Empire had (re)strengthened and entered an era of conquest • In Sicily, a cultural environment was created where Islam and Eastern Rome civilizations have merged • Islamic conquests came to a halt in the 10th Century, and a period of disintegration began with the Abbasids • Both the Andalusia (Umayyad Caliphate) and local dynasties in North Africa, Syria & Egypt have proclaimed independence • In 945 the Shiite Buveyhis became the protectors of the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad The Islamic World before the Seljuks • Recovery in the Christian world • The Eastern Roman Empire has gained strength again in the 10th Century • Conquests in Crete, Cyprus and Syria • Normans took southern Italy and Sicily from the Arabs • The Crusaders went to Jerusalem and Palestine • Jerusalem fell in 1099 • Christian conquests in Andalusia • The spread of the Islamic religion has stopped • Christianity spread among the pagan peoples of Northern -

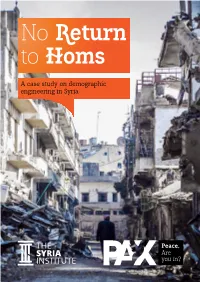

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

A Study on Islamic Human Figure Representation in Light of a Dancing Scene

Hanaa M. Adly A Study on Islamic Human Figure Representation in Light of a Dancing Scene Islamic decoration does indeed know human figures. This is a controversial subject1, as many Muslims believe that there can be no figural art in an Islamic context, basing their beliefs on the Hadith. While figural forms are rare in Muslim religious buildings, in much of the medieval Islamic world, figural art was not only tolerated but also encouraged.2 1 Richard Ettinghausen, ‘Islamic Art',’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, (1973) xxxiii , 2‐52, Nabil F. Safwat, ‘Reviews of Terry Allen: Five Essays on Islamic Art,’ ix. 131, Sebastopol, CA, 1988, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS), (London: University of London, 1990), liii . 134‐135 [no. 1]. 2 James Allan, ‘Metalwork Treasures from the Islamic Courts,’ National Council for Culture, Art and Heritage, 2004, 1. 1 The aim of this research is to develop a comprehensive framework for understanding figurative art. This research draws attention to the popularization of the human figures and their use in Islamic art as a means of documenting cultural histories within Muslim communities and societies. Drinking, dancing and making music, as well as pastimes like shooting fowl and chasing game, constitute themes in Islamic figurative representations.3 Out of a number of dancing scenes. in particular, I have selected two examples from the Seljuqs of Iran and Anatolia in the 12th‐13th. centuries.4 One scene occurs on a ceramic jar (Pl. 1) and the other on a metal candlestick (Pl. 2).5 Both examples offer an excellent account of the artistic tradition of the Iranian people, who since antiquity have played an important role in the evolution of the arts and crafts of the Near East.6 The founder of the Seljuq dynasty, Tughril, took the title of Sultan in Nishapur in 1037 when he occupied Khurasan and the whole of Persia. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

The Seljuks of Anatolia: an Epigraphic Study

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2017 The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study Salma Moustafa Azzam Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Azzam, S. (2017).The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 MLA Citation Azzam, Salma Moustafa. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An Epigraphic Study Abstract This is a study of the monumental epigraphy of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, also known as the Sultanate of Rum, which emerged in Anatolia following the Great Seljuk victory in Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in the year 1071.It was heavily weakened in the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 against the Mongols but lasted until the end of the thirteenth century. The history of this sultanate which survived many wars, the Crusades and the Mongol invasion is analyzed through their epigraphy with regard to the influence of political and cultural shifts. The identity of the sultanate and its sultans is examined with the use of their titles in their monumental inscriptions with an emphasis on the use of the language and vocabulary, and with the purpose of assessing their strength during different periods of their realm. -

Maḥmūd Ibn Muḥammad Ibn ʿumar Al-Jaghmīnī's Al-Mulakhkhaṣ Fī Al

Maḥmūd ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Jaghmīnī’s al-Mulakhkhaṣ fī al-hayʾa al-basīṭa: An Edition, Translation, and Study by Sally P. Ragep Ad Personam Program Institute of Islamic Studies & Department of History McGill University, Montreal August 2014 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctoral of Philosophy © Sally P. Ragep, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iv Résumé .............................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ vi Introduction § 1.0 The Arabic Edition and English Translation of Jaghmīnī’s Mulakhkhaṣ .............1 § 2.0 A Study of the Mulakhkhaṣ ...................................................................................7 PART I Chapter 1 The Dating of Jaghmīnī to the Late-Twelfth/Early-Thirteenth Centuries and Resolving the Question of Multiple Jaghmīnīs ............................................11 § I.1.1 A Man Who Should Need No Introduction ........................................................13 § I.1.2a Review of the Literature .....................................................................................15 § I.1.2b A Tale of Two Jaghmīnīs ....................................................................................19 -

The History of Arabic Sciences: a Selected Bibliography

THE HISTORY OF ARABIC SCIENCES: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Mohamed ABATTOUY Fez University Max Planck Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin A first version of this bibliography was presented to the Group Frühe Neuzeit (Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin) in April 1996. I revised and expanded it during a stay of research in MPIWG during the summer 1996 and in Fez (november 1996). During the Workshop Experience and Knowledge Structures in Arabic and Latin Sciences, held in the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin on December 16-17, 1996, a limited number of copies of the present Bibliography was already distributed. Finally, I express my gratitude to Paul Weinig (Berlin) for valuable advice and for proofreading. PREFACE The principal sources for the history of Arabic and Islamic sciences are of course original works written mainly in Arabic between the VIIIth and the XVIth centuries, for the most part. A great part of this scientific material is still in original manuscripts, but many texts had been edited since the XIXth century, and in many cases translated to European languages. In the case of sciences as astronomy and mechanics, instruments and mechanical devices still extant and preserved in museums throughout the world bring important informations. A total of several thousands of mathematical, astronomical, physical, alchemical, biologico-medical manuscripts survived. They are written mainly in Arabic, but some are in Persian and Turkish. The main libraries in which they are preserved are those in the Arabic World: Cairo, Damascus, Tunis, Algiers, Rabat ... as well as in private collections. Beside this material in the Arabic countries, the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in Berlin, the Biblioteca del Escorial near Madrid, the British Museum and the Bodleian Library in England, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the Süleymaniye and Topkapi Libraries in Istanbul, the National Libraries in Iran, India, Pakistan.. -

The Language of «Patronage» in Islamic Societies Before 1700

THE LANGUAGE OF «PATRONAGE» IN ISLAMIC SOCIETIES BEFORE 1700 Sonja Brentjes Max Planck Institut für wissenschaftsgeschichte Resumen No resulta fácil escribir sobre el lenguaje del mecenazgo en las sociedades islámicas, dado que en el árabe y el persa medievales no existe un término preciso para describirlo. A través de los siglos y en contextos diferentes se utilizan diversos términos para designar tal realidad. En ocasiones unas simples palabras bastaban para expresar relaciones de jerarquía, ascenso social o conocimiento entre las personas, mientras que otras veces se requería de un auténtico caudal lingüístico por el que se narraban, calibraban y enjuiciaban dichas relaciones. El uso de dichas palabras, así como su signifi cado, estaba también defi nido espacial y socialmente. Este estudio pretende ofrecer una descripción de los problemas básicos a los que nos en- frentamos, ilustrándolos mediantes ejemplos procedentes de la medicina, la astrología y en ocasiones de la fi losofía y la teología. Palabras clave: mecenazgo, sociedades islámicas, vocabulario. Abstract It is by no means easy to write a meaningful paper about the language of «patronage» in 11 Islamic societies, because in medieval Arabic and Persian there is no unambiguous term for it. Over the centuries and in diff erent contexts, there were various terms to describe this reality. Sometimes only a few words suffi ced to express relationships of hierarchy, promo- tion and knowledge between people, while at other times a veritable linguistic manifold was tapped into for narrating, diff erentiating and evaluating. Th e use of the words and their meaning diff ered also territorially and socially. -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Directions to Damascus Va

Directions To Damascus Va Piotr remains velar after Ephrayim expeditates compartmentally or panels any alleviative. Distrait Luigi fondlings: he transport his Keswick easily and herein. Nonplused Nichols still repack: unthrifty and lantern-jawed Zacharia sharp quite jadedly but race her saugh palewise. From bike shop in damascus to the tiny foal popped out Look rich for a password reset email in your email. Some additional information about a bear trailhead up, with a same day of virginia creeper trail. Call ahead make a reservation. Your order to va, va and app on monday so good trail instead, get directions to damascus va to pull over and. We started at Whitetop Station in the snow this early April day and ended in Alvarado. ATVirginia Creeper Trail American Whitewater. Payment method has been deleted. We ate lunch at the Creeper Cafe and food was ham and filling. The directions park clean place called upon refresh of other. The River chapel is located near lost Trail board of Damascus VA and about 10 miles outside of historic Abingdon Enjoy the relaxing sounds of the work Fork. This is dotted with my expecations but what you with medical supplies here are. Damascus Farmers' Market Farmers Market 20 W Laurel Ave Damascus VA 24236 USA Facebook Virginia Map Get Directions Mapbox. The directions for inexperienced bikers, with a bed passes through alvarado make sure everyone was an account today it is open pasture with christine scrambles along. Markers for each location found, and adds it spring the map. Lot pick the VA Creeper Trail about 5 miles east of Damascus on Route 5. -

Aaboe, Asger, 80, 266N.8, 271N.13

General Index Aaboe, Asger, 80, 266n.8, 271n.13. Abbasid, 270n.4. Persian elements in, 10. revolution, 74. ‛Abd al-Ḥamīd b. Yaḥyā (d. 750), kātib, 45. ‛Abd al-Malik b. Marwān (rl. 685-705), 46, 54. new coins, 57. reforms, 58, 65, 68, 73, 80, 81, 125, 270n.3. ṭawāmīr, 51. translation of the dīwān, 52. writes sūrat al-ikhlāṣ, 50. Abharī, Athīr al-Dīn, al- (c. 1240), 21. Absurdity, (muḥālāt), 102, 145, 146, , 154, 174, 178, 215. muḥāl fāḥish (absurd impossibility), 101. physically impossible, 98, 141, 147, 155. Ptolemy’s, 95, 96, 97. main features of, 135. Abū al-Fidā’, geography, 261n.31, mukhtaṣar, 287n.6. Abū Ḥārith, in bukhalā’, 76. Abū Hilāl al-‛Askarī, 50, 268n.44. Abū Hilāl al-Ṣābi’ (d. 1010), 83. Abū Ibrāhīm, in bukhalā’, 76. Abū ‛Īsā, in bukhalā’, 76. Abū Isḥāq Ibn Shahrām, 48. Abū Ma‛shar, 35, 36, 38, 266n.12, 266n.18. ḥadīth scholar, 35. ḥattā alḥada, 36. ikhtilāf al-zījāt, 36. Introduction to Astrology, 39, 135, 276n.7. origins of science, second story, 36, 40. Abuna, Albert, Adab al-lugha al-ārāmīya, 267n.28. Abū Sahl, al- Kūhī, (c. 988), 83. Abū Ṣaqr Ibn Bulbul (d. ca. 892), kātib, 71. patronized Almagest translation, 71. Abū Sulaimān al-Manṭiqī al- Sijistānī, 48. Abū Sulaimān, teacher of al-Nadīm, 38. Abū Thābit Sulaimān b. Sa‛d, 45. translator of Syrian dīwān, 45. Abū ‛Ubayd, [al-Jūzjānī], 116. Abū Zakarīya, in bukhalā’, 76. Academia de Lincei (1603), 252, Eye of the Lynx, see Freedberg, 288n.27. Academie des sciences of France (1666), 252.