Page 1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 321 259 CS 212 409 AUTHOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice Walker's the Color Purple

Alice Walker's The Color Purple RUTH EL SAFFAR, University of Illinois Alice Walker's The Color Purple (1982) is the work that has made a writer who has published consistently good writing over the past decade and a half into some thing resembling a national treasure. Earlier works, like her collection of short stories, In Love and Trouble (1973), and her poems, collected under the title Revo lutionary Petunias and Other Poems (1973), have won awards.' And there are other novels, short stories, poems, and essays that have attracted critical attention.2 But with The Color Purple, which won both the American Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, Alice Walker has made it onto everyone's reading list, bringing into our consciousness with clarity and power the long-submerged voice of a black woman raised southern and poor. Although Celie, the novel's principal narrator/character, speaks initially from a deeply regional and isolated perspective, both she and the novel ultimately achieve a vision which escapes the limitations of time and space. The Color Purple is a novel that explores the process by which one discovers one's essential value, and learns to claim one's own birthright. It is about the magical recovery of truth that a world caught in lies has all but obscured. Shug Avery, the high-living, self-affirming spirit through whom the transfor mation of the principal narrator/character takes place reveals the secret at a crucial point: "God is inside you and inside everybody else. You come into the world with God. But only them that search for it inside find it. -

English IV AP, DC, and HD 2021 Summer Reading

Northside ISD Curriculum & Instruction English IV AP, DC, & HD Summer Reading Welcome to Advance English IV Literature! Reading is one of the best things you can do to prepare yourself for the challenges of the upcoming school year and beyond. Now more than ever, it is important to sharpen your critical reading skills, expand your vocabulary and enhance your focus and imagination - all in the comfort of your own home. There’s no better way to accomplish this than by sitting down with a good book. We are asking that you, as an Advance Literature student, read at least one novel of your choice this summer. There is no other assignment than to read; however, be ready to complete a SUMMATIVE assignment on your summer reading book when school starts. Remember, you can choose any book you wish to read - it does not have to be on the list below. The following titles are included just to give you some ideas. The novels marked by an asterisk indicate those which are on the Northside approved book list. Other titles may contain adult themes and content, so we encourage you to do some research before selecting a title. You can check out digital books on Sora, Libby, and Overdrive through your school library. HAPPY READING! Romance 1. All the Ugly and Wonderful Things by Bryn Greenwood 2. Frankly In Love by David Yoon 3. The Importance of Being Earnest* by Oscar Wilde 4. Jane Eyre* by Charlotte Brontë 5. Just Listen by Sarah Dessen 6. Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel 7. -

Alice Walker the Handmaid's Tale

Junior Research Suggested Book List Inferno- Dante Alighieri The Color Purple – Alice Walker The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen Go Tell It on the Mountain – James Baldwin Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte Death Comes for the Archbishop – Willa Cather My Antonia – Willa Cather Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad Tale of Two Cities – Charles Dickens Great Expectations – Charles Dickens Love in the Time of Cholera – Gabriel Garcia Marquez Farewell to Arms – Earnest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises – Earnest Hemingway Cranford – Elizabeth Gaskell The Scarlett Letter – Nathaniel Hawthorne The Trial – Franz Kafka Paradise Lost – John Milton The Road – Cormac McCarthy The Bluest Eye – Toni Morrison The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plath Fountainhead – Ayn Rand All Quiet on the Western Front- Erich Maria Remarque The Jungle – Upton Sinclair East of Eden – John Steinbeck The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – Robert Louis Stevenson The Joy Luck Club – Amy Tan Vanity Fair – William Makepeace Thackeray The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – Mark Twain Slaughterhouse Five – Kurt Vonnegut War of the Worlds - H.G. Wells The Age of Innocence – Edith Wharton The Picture of Dorian Gray- Oscar Wilde Native Son – Richard Wright One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – Ken Kesey A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man – James Joyce The Picture of Dorian Gray – Oscar Wilde **These books are only suggestions and you may choose a work not on this list only with approval from Ms. Goldberg. Please email Ms. Goldberg if you are considering straying from the list. . -

Mbue, Imbolo. Behold the Dreamers 2017 Winner of the Pen/Faulkner

Mbue, Imbolo. Behold the Dreamers 2017 winner of the Pen/Faulkner Award, this novel details the experiences of two New York City families during the 2008 financial crisis, an immigrant family from Cameroon, the Jonga family, and their wealthy employers, the Edwards family. Call #: FIC Mbue Morrison, Toni. Beloved (you may choose any of Morrison’s books for credit) Recommended: The Bluest Eye The 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Fictions book is set after the American Civil War and it is inspired by the life of Margaret Garner, an African American who escaped slavery in Kentucky in late January 1856 by crossing the Ohio River to Ohio, a free state. Captured, she killed her child rather than have her taken back into slavery. Call #: FIC Morrison Lalami, Laila. The Other Americans. From the Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of The Moor’s Account, this is a novel about the suspicious death of a Moroccan immigrant–at once a family saga, a murder mystery, and a love story, informed by the treacherous fault lines of American culture. Call #: FIC Lalami Noah, Trevor. Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood The book details Trevor Noah growing up in his native South Africa during the apartheid era. As the mixed-race son of a white Swiss father and a black mother , Noah himself was classified as a "colored” in accordance to the apartheid system of racial classification. According to Noah, he stated that even under apartheid, he felt trouble fitting in because it was a crime "for [him] to be born as a mixed-race baby", hence the title of his book. -

The Color Purple: Evaluation of the Film Adaptation Chelsey Boutan College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 8 Article 11 4-1-2011 The Color Purple: Evaluation of the Film Adaptation Chelsey Boutan College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Boutan, Chelsey (2010) "The Color Purple: Evaluation of the Film Adaptation," ESSAI: Vol. 8, Article 11. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol8/iss1/11 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Boutan: <em>The Color Purple</em>: Evaluation of the Film Adaptation The Color Purple: Evaluation of the Film Adaptation by Chelsey Boutan (English 1154) hen Alice Walker saw the premiere of her Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Color Purple on the big screen, she didn't like the movie at all. But after receiving many letters and Wpositive reactions, Walker realized that the film may not express her vision, but it does carry the right message. Walker said, "We may miss our favorite part... but what is there will be its own gift, and I hope people will be able to accept that in the spirit that it's given" ("The Color Purple: The Book and the Movie"). Since the film's premiere 25 years ago, Walker has been asked over and over again, "Did you like the movie?" Although her response sometimes varies, she most frequently answers, "Remember, the movie is not the book" ("The Color Purple: The Book and the Movie"). -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

AP Literature Summer Assignment Information

HS East AP Literature Summer Assignment Ms. Morgan / HS East / W24 [email protected] NOTE: Guidance processes course requests and prerequisites over the summer, usually confirming enrollments in July. Attending this meeting DOES NOT MEAN you are officially in the course yet. If you complete this assignment before Guidance confirms placement, you do so AT YOUR OWN RISK! Materials: Looseleaf Binder (1.5” to 2” with the following recommended 5-section headings: Class Discussion / Writing / Reading Notes / ILE Notes / Vocabulary); Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (or equivalent; NOT “student” dictionary) Sticky Notes (Post-Its®, etc; multi-colored 3” & 1” squares are most handy) Course Overview: Between now and May, you will be aiming to achieve mastery over an extensive range of literary genres and time periods from at least the Renaissance through contemporary literature (though the Ancient and Medieval eras also bear much sweet fruit), and represented by as many individual works of literature as possible, from full-length novels and plays to short stories and poems. Competence with as much literary terminology as possible combined with knowledge of relevant historical and cultural contexts and development of a strong analytic writing style further support success on the exam — and well beyond. I am honored to share that I hear from former students every year who report that this course made the difference for them — regardless of their future fields of study. Summer Assignment, Part A: Reading for Fun and Profit! (or at least for credit...) -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

The Color Purple Study Guide

CREATIVE TEAM ALICE WALKER (Novel) won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for her third novel, The Color Purple, which was made into an internationally popular film by Steven Spielberg. Her other best-selling novels, which have been translated into more than two dozen languages, include By the Light of My Father’s Smile, Possessing the Secret of Joy, and The Temple of My Familiar. Her most recent novel, Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart, was published in 2004. Ms. Walker is also the author of several collections of short stories, essays, and poems as well as children’s books. Her work has appeared in numerous national and international journals and magazines. An activist and social visionary, Ms. Walker’s advocacy on behalf of the dispossessed has, in the words of her biographer, Evelyn C. White, “spanned the globe.” MARSHA NORMAN (Book) won the Pulitzer Prize for her play ’Night, Mother and a Tony Award for her book of the musical The Secret Garden. Her other plays include Getting Out, Traveler in the Dark, Sarah and Abraham, Trudy Blue, The Master Butchers Singing Club, and Last Dance. She also has written a novel, The Fortune Teller. She has numerous film and TV credits, Grammy and Emmy nominations, and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers. Ms. Norman is a native of Kentucky who lives in New York City and Long Island. BRENDA RUSSELL (Music & Lyrics) has a unique musical perspective, intimate voice, and prolific treasure trove of lyrics that prove a truly glowing talent only deepens with time. -

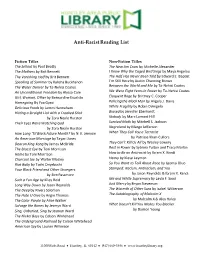

Anti-Racist Reading List

Anti-Racist Reading List Fiction Titles Non-Fiction Titles The Sellout by Paul Beatty The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Mothers by Brit Bennett I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett The Half Has Never Been Told by Edward E. Baptist Speaking of Summer by Kalisha Buckhanon I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo Eloquent Rage by Brittney C. Cooper Homegoing By Yaa Gyasi Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis Delicious Foods by James Hannaham White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick Biased by Jennifer Eberhardt by Zora Neale Hurston Nobody by Marc Lamont Hill Their Eyes Were Watching God Survival Math by Mitchell S. Jackson by Zora Neale Hurston Negroland by Margo Jefferson How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? by N. K. Jemisin When They Call You a Terrorist An American Marriage by Tayari Jones by Patrisse Khan-Cullors Deacon King Kong by James McBride They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison Rest in Power by Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin Home by Toni Morrison How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley Heavy by Kiese Laymon Riot Baby by Tochi Onyebuchi So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo Your Black Friend and Other Strangers Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ben Passmore by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X.