Music Forum Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The George London Foundation for Singers Announces Its 2016-17 Season of Events

Contact: Jennifer Wada Communications 718-855-7101 [email protected] www.wadacommunications.com THE GEORGE LONDON FOUNDATION FOR SINGERS ANNOUNCES ITS 2016-17 SEASON OF EVENTS: • THE RECITAL SERIES: ISABEL LEONARD & JARED BYBEE PAUL APPLEBY & SARAH MESKO AMBER WAGNER & REGINALD SMITH, JR. • THE 46TH ANNUAL GEORGE LONDON FOUNDATION AWARDS COMPETITION “This prestigious competition … now in its 45th year, can rightfully claim to act as a springboard for major careers in opera.” -The New York Times, February 18, 2016 Isabel Leonard, Jared Bybee, Paul Appleby, Sarah Mesko, Amber Wagner, Reginald Smith, Jr. (Download photos.) The George London Foundation for Singers has been honoring, supporting, and presenting the finest young opera singers in the U.S. and Canada since 1971. Upon the conclusion of the 20th year of its celebrated recital series, which was marked with a gala in April featuring some of opera’s most prominent American and Canadian stars, the Foundation announces its 2016-17 season of events: The George London Foundation Recital Series, which presents pairs of outstanding opera singers, many of whom were winners of a George London Award (the prize of the foundation’s annual vocal competition): George London Foundation for Singers Announces Its 2016-17 Season - Page 2 of 5 • Isabel Leonard, mezzo-soprano, and Jared Bybee, baritone. Mr. Bybee won an Encouragement Award at the 2016 competition. Sunday, October 9, 2016, at 4:00 pm • Paul Appleby, tenor, and Sarah Mesko, mezzo-soprano. Mr. Appleby won his George London Award in 2011, and Ms. Mesko won hers in 2015. Sunday, March 5, 2017, at 4:00 pm • Amber Wagner, soprano, and Reginald Smith, Jr., baritone. -

23 September 2011 Page 1 of 19 SATURDAY 17 SEPTEMBER 2011 4:43 AM Saint-Saëns, Camille (1835-1921) Arr

Radio 3 Listings for 17 – 23 September 2011 Page 1 of 19 SATURDAY 17 SEPTEMBER 2011 4:43 AM Saint-Saëns, Camille (1835-1921) arr. R. Klugescheid SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b014fl8m) My Heart At Thy Sweet Voice - Cantabile from 'Samson & John Shea presents a concert of music by Telemann, J S Bach Delilah' arranged for violin, cello and piano and W F Bach with the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra Moshe Hammer (violin), Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi (cello), William Tritt (piano) 1:01 AM Telemann, Georg Philipp [1681-1767] 4:47 AM Overture in D from 'Tafelmusik ll' TWV 55:D1 Copland, Aaron (1900-1990) Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Petra Müllejans (conductor) El Salón México San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas 1:23 AM (conductor) Bach, Johann Sebastian [1685-1750] Ich bin in vergnügt - Cantata BWV 204 5:01 AM Julia Kleiter (soprano), Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Petra Debussy, Claude (1862-1918) Müllejans (conductor) Golliwog's Cake-walk from Children's Corner Suite (1906-8) Donna Coleman (piano) 1:57 AM Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann [1710-1874] 5:04 AM Flute Concerto in D Sáry, László (b.1940) Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Petra Müllejans (conductor) Kotyogó ko egy korsóban (Pebble Playing in a Pot) (1976) Aurél Holló & Zoltán Rácz (marimbas) 2:19 AM Bach, Johann Sebastian [1685-1750], Bach, Wilhelm 5:14 AM Friedemann [1710-1874] Wolf, Hugo (1860-1903) Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen Cantata BWV 51 Italian serenade for string quartet Julia Kleiter (soprano), Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Petra Bartók Quartet Müllejans (conductor) 5:21 AM 2:38 AM Verdi, -

Program Notes

Program Notes SYNOPSIS OF SCENES Antwerp, first half of the 10th century ACT I: The king’s court of judgment, on the banks of the Scheldt ACT II, Scene 1: Outside Elsa’s castle Scene 2: The courtyard of the cathedral ACT III, Scene 1: The bridal chamber Scene 2: The banks of the Scheldt ACT I swear vengeance. When Elsa appears in a In Antwerp, on the banks of the window, Ortrud attempts to sow Scheldt, a herald announces King Henry, distrust in the girl’s mind, preying on who asks Count Telramund to explain her curiosity, but Elsa innocently offers why the Duchy of Brabant is torn by strife the scheming Ortrud friendship. Inside, and disorder. Telramund accuses his while the victorious knight is young ward, Elsa, of having murdered proclaimed guardian of Brabant, the her brother, Gottfried, heir to Brabant’s banned Telramund furtively enlists four Christian dynasty. (Gottfried was actually noblemen to side with him against his enchanted by the evil Ortrud, whom newfound rival. At the cathedral Telramund has wed.) When Elsa is called entrance, Ortrud and Telramund to defend herself, she relates a dream of a attempt to stop the wedding—she by knight in shining armor who will come suggesting that the unknown knight is to save her. The herald calls for the in fact an impostor, he by accusing Elsa’s defender, but only when Elsa prays does bridegroom of sorcery. The crowd stirs the knight appear, arriving in a boat uneasily. Though troubled by doubt, magically drawn by a swan. He pledges Elsa reiterates her faith in the knight his troth to her on condition that she before they enter the church, accompa- never ask his name or origin. -

Summer 2008 Dess’ Stiller Frieden Dich Umfing? Volume 5, Number 3 —Parsifal

Wagneriana Du konntest morden? Hier im heil’gen Walde, Summer 2008 dess’ stiller Frieden dich umfing? Volume 5, Number 3 —Parsifal From the Editor he Boston Wagner Society will turn five on September 20. We are planning some festivities for that day that will include live music. This special event will be open to members and their guests only. Invitations will be forthcom- T ing. This year we have put in place new policies for applying for tickets to the Bayreuth Festival. Before you send in your application for 2009, please make sure that you have read these policies (see page 7). Here is a sneak preview of the next season’s events: a talk by William Berger, co-host of Sirius Met Opera’s live broad- casts and author of Wagner without Fear: Learning to Love–and Even Enjoy–Opera’s Most Demanding Genius (on October 18); a talk by Professor Robert Bailey, a well-known Wagnerian scholar and the author of numerous articles on Wagner, titled “Wagner’s Beguiling Tristan und Isolde and Its Misunderstood Aspects” (on November 15); an audiovisual presentation comparing the Nibelungenlied with Wagner’s Ring Cycle, by Vice President Erika Reitshamer (winter 2009). We will add more programs as needed. Due to space limitations, in this issue we are omitting part 4 of Paul Heise’s article “The Influence of Feuerbach on the Libretto of Parsifal.” The series will resume in the next issue. –Dalia Geffen, President and Founder Wagner from a Buddhist Perspective Paul Schofield, The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring (New York: Amadeus Press, 2007) he Redeemer Reborn is a very important book. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0154-55 Notes

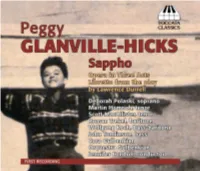

Peggy Glanville-Hicks and Lawrence Durrell discuss Sappho, play through the inished piano score Greece, 1963 Comprehensive information on Sappho and foreign-language translations of this booklet can be found at www.sappho.com.au. 2 Cast Sappho Deborah Polaski, soprano Phaon Martin Homrich, tenor Pittakos Scott MacAllister, tenor Diomedes Roman Trekel, baritone Minos Wolfgang Koch, bass-baritone Kreon John Tomlinson, bass Chloe/Priestess Jacquelyn Wagner, soprano Joy Bettina Jensen, soprano Doris Maria Markina, mezzo soprano Alexandrian Laurence Meikle, baritone Orquestra Gulbenkian Coro Gulbenkian Jennifer Condon, conductor Musical Preparation Moshe Landsberg English-Language Coach Eilene Hannan Music Librarian Paul Castles Chorus-Master Jorge Matta 3 CD1 Act 1 1 Overture 3:43 Scene 1 2 ‘Hurry, Joy, hurry!’... ‘Is your lady up? Chloe, Joy, Doris, Diomedes, Minos 4:14 3 ‘Now, at last you are here’ Minos, Sappho 6:13 4 Aria – Sappho: ‘My sleep is fragile like an eggshell is’ Sappho, Minos 4:17 5 ‘Minos!’ Kreon, Minos, Sappho 5:14 6 ‘So, Phaon’s back’ Minos, Sappho, Phaon 3:19 7 Aria – Phaon: ‘It must have seemed like that to them’ Phaon, Minos, Sappho 4:33 8 ‘Phaon, how is it Kreon did not ask you to stay’ Sappho, Phaon, Minos 2:24 Scene 2 – ‘he Symposium’ 9 Introduction... ‘Phaon has become much thinner’... Song with Chorus: he Nymph in the Fountain Minos, Sappho, Chorus 6:22 10 ‘Boy! Bring us the laurel!’... ‘What are the fortunes of the world we live in?’ Diomedes, Sappho, Minos, Kreon, Phaon, Alexandrian, Chorus 4:59 11 ‘Wait, hear me irst!’... he Epigram Contest Minos, Diomedes, Sappho, Chorus 2:55 12 ‘Sappho! Sappho!’.. -

Opera & Music | Spring 2014

OPERA & MUSIC | SPRING 2014 THE ROYAL OPERA REPERTORY PAGE DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN 2 THE COMMISSION / CAFÉ KAFKA 4 L’ORMINDO (AT SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE) 6 THROUGH HIS TEETH 7 THE CRACKLE 8 FAUST 9 JONAS KAUFMANN – WINTERREISSE 11 LA TRAVIATA 12 LE NOZZE DI FIGARO 14 TOSCA 15 DIALOGUES DES CARMÉLITES 17 BABYO / SENSORYO 19 LUNCHTIME RECITALS AND EVENTS 21 PRESS OFFICE CONTACTS 24 For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/press DIE FRAU OHNE SCHATTEN NEW PRODUCTION Richard Strauss 14, 17, 20, 26, 29 March at 6pm; 23 March at 3pm 2 April at 6pm • Co-production with La Scala, Milan. • Generously supported by Sir Simon and Lady Robertson, Hamish and Sophie Forsyth, The Friends of Covent Garden and an anonymous donor. • Die Frau ohne Schatten will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 on 29 March 2014 at 5.45pm. The Royal Opera celebrates the 150th anniversary of Strauss’s birth with a new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten , one of three Strauss operas being presented at the Royal Opera House this Season, all with librettos by Hugo von Hofmannsthal on mythical themes. Elektra was revived in October 2013 and Ariadne auf Naxos will be revived in June 2014. This production of Die Frau ohne Schatten is new to the Royal Opera House, and is a co-production with La Scala, Milan, where it was first seen in 2012. German director Claus Guth makes his UK and Royal Opera debut with this production, which explores themes of the search for identity and the psychological power of dreams, and vividly illustrates the plight of the central character of the Empress, a woman trapped between two repressive worlds. -

Cincinnati Moving with the Times

15 International Arts Manager September 2002 Cincinnati Moving with the times Cincinnati is on the brink of international cultural recognition. Paul Cutts visits a city coming to terms with its new-found status TANDING ON THE NORTHERN ority complex, yet there is a deep sense of opera alone was given $900,000 by the banks of the Ohio river, Cincinnati civic and cultural pride in the city and Fund, around 15 per cent of its entire sboasts the largest concert hall in the corporate community,' says Muni, a annual operating budget. the US and the country's second oldest native of NewJersey. There is also a long Becoming a private arts benefactor is opera company. It is also home to a tradition of supporting the arts here. It is a strong part of local tradition and is nationally respected ballet troupe, a a sophisticated town in terms of the actively encouraged among the upper symphony orchestra counting such cultural mood.' echelons of Cincinnati society. But nor greats as Leopold Stokowski and Fritz Muni has been surprised at the are they averse to boldness: a new home Reiner among its former music directors dynamism of the last few years. 'If I look for the city's Contemporary Arts Center - and has the oldest choral gathering - the back on where the community was when currently under construction and funded Cincinnati May Festival - in the western I arrived, it has really zoomed forward,' in part by generous private gifts - has hemisphere. he comments. 'At the time there was been designed by avant-garde architect Yet for aplace that is ranked in the top nothing special going on. -

Lohengrin RICHARD WAGNER

Richard Wagner Lohengrin RICHARD WAGNER Ópera romántica en tres actos Libreto de Richard Wagner Del 19 de marzo al 5 de abril Temporada 2019-2020 Temporada 1 Patronato de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comisión ejecutiva de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Presidente de honor Presidente Joaquim Torra Pla Salvador Alemany Mas Presidente del patronato Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives, Francesc Vilaró Casalinas Vicepresidenta primera Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresidente segundo Vocales representantes del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona Andrea Gavela Llopis Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresidente tercero Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta cuarta Vocales representantes de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocales representantes del Consejo de Mecenazgo Francesc Vilaró Casalinas, Àngels Barbarà Fondevila, Àngels Elisa Duran Montolio y Luis Herrero Borque Ponsa Roca, Pilar Fernández Bozal Secretario Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Joaquim Badia Armengol Santiago Fisas Ayxelà, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Santiago de Director general Torres Sanahuja, Joan Francesc Marco Conchillo Valentí Oviedo Cornejo Vocales representantes del -

Lohengrin RICHARD WAGNER

Richard Wagner Lohengrin RICHARD WAGNER Òpera romàntica en tres actes Llibret de Richard Wagner Del 19 de març al 5 d'abril Temporada 2019-2020 Temporada 1 Patronat de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comissió Executiva de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu President d’honor President Joaquim Torra Pla Salvador Alemany Mas President del patronat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives, Francesc Vilaró Casalinas Vicepresidenta primera Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresident segon Vocals representants de l'Ajuntament de Barcelona Andrea Gavela Llopis Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresident tercer Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta quarta Vocals representants de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocals representants del Consell de Mecenatge Francesc Vilaró Casalinas, Àngels Barbarà Fondevila, Àngels Elisa Duran Montolio i Luis Herrero Borque Ponsa Roca, Pilar Fernández Bozal Secretari Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Joaquim Badia Armengol Santiago Fisas Ayxelà, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Santiago de Director general Torres Sanahuja, Joan Francesc Marco Conchillo Valentí Oviedo Cornejo Vocals representants de l'Ajuntament de Barcelona Josep Maria -

Upload the Biographical Leaflet

ACADÉMIE LIST OF PARTICIPANTS BIOGRAPHIES OPÉRA DE-CI DE-LÀ WORKSHOP: JANUARY 27 — 29, 2021 RESIDENCY: JUNE 7 — 12, 2021 OPÉRA DE-CI DE-LÀ RESIDENCY Opéra de-ci de-là residency offers a training program that explores the strengths, the stakes, and the potential for change in the opera industry. The program aims at training young creators and performers to create collaborative and immersive operas, in a setting that favors intercultural dialogue and interdisciplinary exchange. By investigating innovative and creative processes, the program provides young artists with the opportunity to develop short-form performances and offers them an immersive experience in the public space. The second edition of the Opéra de-ci de-là residency originally scheduled in March and June 2020 will last for a full season. After a two-day videoconferencing seminar in June 2020, 4 other sessions are held online during the fall, then 2 face-to-face sessions in January and June 2021. MENTOR PARTICIPANTS Gathering four composers, four stage directors, eight singers, four instrumentalists ANTHONY HEIDWEILLER CHRISTIAN ANDREAS — BARITONE and two authors, the residency aims at underscoring the importance of storyline in SINGER AND ARTISTIC ASSOCIATED GEORDIE BROOKMAN — STAGE intellectual discussions and the creative process. In the context of the pandemic, DIRECTOR OF THE OPERA FORWARD DIRECTOR it also offers a unique space for reflection about the role of art in society today and FESTIVAL OF AMSTERDAM SIMONA CASTRIA — SAXOPHONE how art can be used to respond in times of crisis. The theatre director and 17th- ÉLISE CHAUVIN — SOPRANO century literature and modern science historian Frédérique Aït-Touati, contributed AMY CRANKSHAW — COMPOSER to the reflection with her research on Harmonices Mund by the seventeenth-century JOSIE DAXTER — STAGE DIRECTOR astronomer Johannes Kepler. -

No. 101, September 2005 a Letter from the President Registered Office

No. 101, September 2005 A Letter from the President Newsletter Highlights P.2 P.3 P.10 P.10 PATRON: Sir CHARLES MACKERRAS HONORARY LIFE MEMBERS: Prof MICHAEL EWANS Mr RICHARD KING Mr HORST HOFFMAN Mr JOSEPH FERFOGLIA Mrs BARBARA McNULTY OBE Registered Office: 75 Birtley Towers, 8 Birtley Place, Elizabeth Bay NSW 2011 Print Post Approved PP242114/00002 A Letter from the President cont. FOR YOUR DIARY Parsifal New Zealand International Arts Festival in partnership with Friday, 17 and Sunday, the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra – 2 performances 19 March during the 2006 Festival – see details below. COMING EVENTS 2005 September 18 Panel led discussion of Bayreuth 2005 performances Goethe Institut 2:00PM October 16 Composer Nigel Butterly to talk on Liszt and Wagner Goethe Institut 2:00PM November 20 Alan Whelan “Perception and Reception of Wagner in the Nazi period” Goethe Institut 2:00PM December 11 End of year function – Please bring a plate Goethe Institut 2:00PM Goethe-Institut address 90 Ocean Street Woollahra (corner of Jersey Road) COMMITTEE 2004-2005 President and Membership Roger Cruickshank 9357 7631 Secretary Vice President Julian Block 9337 6978 Treasurer Michael Moore 9363 2281 Secretary Mary Haswell 9810 5532 Members Dennis Mather 9560 1860 Newsletter Editor Terence Watson 9517 2786 Public Officer Alasdair Beck 9358 3922 Wagner Society in NSW Inc - Announcement of Newsletter Article Competition ANNOUNCEMENT The Wagner Society in NSW Inc celebrates the 25th Anniversary of its foundation meeting in October 2005. As part of its activities to mark the occasion, the Society is announcing a competition for articles for publication in its Newsletter.