When I Told Jersey Joe Walcott That I Was Sitting in the Eighth Row at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson Intends to Run Fof Mayor

Workshop·on college funding to be held Society to hold Western event New city planning director named SPORTS MENU TIPS A free workshop on the "9 Ways To Beat The The American Cancer Society, Cuyahoga Divi Mayor Jane Campbell recently named Robert High Cost Of College" will be held on Tuesday, January 25 sion, plans to rope in Greater Clevelanders with what should Brown as the new city planning director. The city planning Cavs Beat Boozer's Tips For from 6:30p.m. to 7:30p.m. at the Solon High School be the most extraordinary party in Ohio: the Cattle Baron's director oversees the city's long term land use and zoning Lecture Hall, 33600 Inwood Road in Solon. The workshop BaJI. The inaugural Cattle Baron's BaJI will be Saturday plans aJong with other responsibilities. The position opened Jazz On Road Trip Winter Parties will cover many topics, including how to double or even April 9, in the CLub Lounge at Cleveland Bown's Stadium. up after CampbeiJ chose former City Planning director triple your eligibility for financial aid, how to construct a Tickets and sponsorship opportunities are available now by Chis Ronayne as her new chief of staff. Brown has worked plan to pay college costs, and what colleges will give you calling (216) 241-11777. The Northern Ohio Toyota Deal for the City Planning Commission for 19 years. For the See Page 9 See Page 10 the best financial aid packages. Reservations are required. ers have jumped in the driver's seat as the event's present last 17 years, Brown was the assistant city planning direc For more information call (888) 845-4282. -

If,Epte% Meitieeta

if,epte% meitieeta VOLUME XX WASHINGTON, D.C., JULY-AUGUST, 1966 NUMBER 106 PACIFIC Cleveland's brief and inspirational discuss Bible truths with Mr. Moore. stay, several church appointments An appointment was arranged and General Conference Visitors were arranged for him. In the middle Elder Fountain was able to give of the week, on Wednesday night, he Archie Moore his first Bible study with in the Pacific Union spoke to a large congregation at the regard to the Adventist faith. Mr. Philadelphian church in San Fran- Moore, who was then residing in San DURING the month of April and the cisco. On Sabbath morning, May 7, Diego, California, was later contacted first part of May the Regional con- he again spoke to a packed audience in the evangelistic Go Tell visitation gregations throughout California have at the Normandy Avenue church in program of Evangelist Eric Ward, been thrilled with the visits from some Los Angeles, and on Sabbath after- who was building up a program of a of our General Conference brethren. noon he was the guest speaker at a large evangelistic campaign in the F. L. Peterson and C. E. Moseley large union meeting in the new city of San Diego. During the course have both traveled up and down our Tamarind church in Compton, South of this Go Tell campaign Mr. Moore California Coast and have had speak- Los Angeles, where many were thrilled was contacted time and again and ing engagements in many churches. with his dynamic message. had the opportunity to study the Fam- Congregation after congregation have We are more than grateful for the ily Bible Course that was presented expressed their appreciation for the inspirational visit of these godly men by the house-to-house visitation in the messages that have been given by in our midst during these weeks pre- Go Tell campaign of this time. -

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013 The IBRO online newsletter is an extension of the Quarterly IBRO Journal and contains material not included in the latest issue of the Journal. Newsletter Features 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton The Boxing Biographies Volume # 9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell Book Recommendation: Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. Chouinard. Book Review Tale of The “Kid” by Randi Bjornstad, The Register Guard Member inquiries, nostalgic articles, and obituaries submitted by several members. Special thanks to Mike Casey, Steve Canton, Henry Hascup, J.J. Johnston, Rick Kilmer, Harry Otty and Rob Snell, for their contributions to this issue of the newsletter. Keep Punching! Dan Cuoco International Boxing Research Organization Dan Cuoco Director, Editor and Publisher [email protected] All material appearing herein represents the views of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). © 2013 IBRO (Original Material Only) CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 3 Member Forum 5 IBRO Apparel 43 Final Bell FEATURES 6 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley 8 California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey 11 Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton 14 The Boxing Biographies Volume #9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS & REVIEWS 33 Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. -

SONNY LISTON and the TORN TENDON Arturo Tozzi, MD, Phd

SONNY LISTON AND THE TORN TENDON Arturo Tozzi, MD, PhD, AAP Center for Nonlinear Science, University of North Texas, PO Box 311427, Denton, TX 76203-1427, USA [email protected] The first Liston-Clay fight in 1964 is still highly debated, because Liston quitted at the end of the sixth round claiming a left shoulder injury. Here we, based on the visual analysis of Sonny’s movements during the sixth round, show how a left shoulder’s rotator cuff tear cannot be the cause of the boxer failing to answer the bell for the seventh round. KEYWORDS: boxing; Muhammad Ali; World Heavyweight Championship; Miami Beach; rotator cuff injury The first fight between Sonny Liston and Cassius Clay took place on February 25, 1964 in Miami Beach. Liston failed to answer the bell for the seventh round and Clay was declared the winner by technical knockout (Remnick, 2000). The fight is one of the most controversial ever: it was the first time since 1919 that a World Heavyweight Champion had quit sitting on his stool. Liston said he had to quit because of a left shoulder injury (Tosches, 2000). However, there has been speculation since about whether the injury was severe enough to actually prevent him from continuing. It has been reported that Sonny Liston had been long suffering from shoulders’ bursitis and had been receiving cortisone shots, despite his notorious phobia for needles (Assael 2016). In training for the Clay fight, it has been reported that he re- injured his left shoulder and was in pain when striking the heavy bag. -

Ohio, the Commencement Was Strange,” Said Louis Gol- Speaker Richard Poutney Advised Phin, Who Lives Next Door

SPORTS MENU TIPS Cadillac show to be held Kid’s Corner Arts Center to present a Cotton Ball The Cadillac LaSalle Club will be hosting the Foluke Cultural Arts Center, Inc. will present it’s “Legacy of Cadillac” show on Sunday, august 19 from 10:00 Ronette Kendell Bell-Moore, first Cotton Ball, (dinner dance) on Saturday, July 28 at Ivy’s Raynell Williams Turn Your Picnic a.m. until 4:00 p.m. at Legacy Village, at the corner of Rich- who is two and a half years old and Catering at GreenMont, 800 S. Green Road from 9 p.m. - 2 mond and Cedar Roads in Lyndhurst. The show is a free, fam- a.m. The attire is casual summer white and tickets are $20.00 Wins Boxing Title Into A Party the daughter of Kendall Moore and ily friendly event. Fins, food, fashions and fun will rule as Jemonica Bell. Her favorite food is in advance and $25.00 the day of the event. A free cruise will be given away as a door prixze. Winner must be present. over 100 classic Cadillacs of all years and types will compete cheese and watermelon. Her favorite for trophies to be awarded at 3:00 p.m. This will be the largest Proceeds benefit Arts Center programming for children and See Page 6 See Page 7 and most prestigious gathering of important Cadillacs in seven toy and character is Dora. She has a youth in need. For information, please refer to www.foluke- states. For information, call Chris Axelrod, (216) 451-2161. -

To Download the PDF File

Welcome To CanbyCanby Minnesota AA 20212021 PublicationPublication ofof TheThe CanbyCanby NewsNews 2 Table of Contents WelcomeWelcome toto CanbyCanby Welcome to Canby, Minnesota, a small town with a lot to Some “insider knowledge” about the town: offer! - The KT - If you ask directions to the golf course, people will Whether you’re just visiting or here to stay, come with us probably tell you it’s two miles out on the KT. This stands for on our stroll around Canby to see some of its historical sites “King of Trails” and is the local term for County Road 13/190th and amenities. Join us at the fun events that happen through- Street. It runs north out of Canby for 12 miles and then ends at out the year, and get active in the community with the numer- County Road 12. ous clubs and organizations - there’s always something fun - The Vo-Tech - Minnesota West Community & Technical Col- for you to get involved in! lege was originally called a vocational-technical school; it got Canby has a population of 1,795 (as of the 2010 census) shortened to “vo-tech,” and that name has stuck. and is located in the west-central portion of Yellow Medicine - 1st Street - Canby has two 1st Streets. The one referred to County at an altitude of 1,243 feet. most often is Highway 68, but 1st Street South is located just It is approximately 165 miles west of Minneapolis-St. Paul, one block over and runs by the Sanford Clinic entrance and be- 106 miles north of Sioux Falls, S.D., and 175 miles south of hind Canby Farmers Grain until it meets Poplar Avenue South. -

Walcott in 1 Punch KO 10 ^ Tragedy

A RHH: ms\ ': '•' I" WWI W MB Ike, Sugar, Ez Dethroned; Who's Next? THE OHIO J - •••—g * **^*»— \%:*n High st. 10 Poop**** Walcott In 1 Punch KO ^ PITTSBURGH.—Four tune* previously a challenger but taever a winner, ancient Jersey Joe Walcott rewrote THLZ OHIO M VOL. J. Wa. 7 SATURDAY, JULY 28, 1951 COLUMBUS. OHIO boxing'* Cinder*?! I * Story by ocotriog a one-punch seventh •round kayo over Champion Eaaanrl Charles of Cincinnati before a shocked throng of 30,000 fane here at Forbes INEL field Wednesday night. Thus, the up.iet Mtrinir, be . gun with Ike Williams' de* coming in with a hard right m«*e in the lightweight di- hand. VOL. 3, No. 6 Saturday, July 21, 1951 CoJumbae, Ohio vi-tioii. Sugar Ray Robin- Ex fell forward, rolled aon'a fumbling of the mid over and making a dee- dleweight crown m London perate effort to rise, as Tragedy a week aft*o, w tarried over the count reached nine, Sports Gleanings into the heavyweight divi slumped on his face and sion, mo-rt lucrative of the the year's biggest sports lot, and where thi* crazy story was born. Thc kayo •pin of up.net event** will end was recorded at 55 sec no one dares predict. onds of the seventh round. Turpin Gives Boxing Needed Walcott had been refer That's the fight simply. red to by many as "Often a There were no sensational beat man but never a bride," early round exchanges and and along with the Drornot- the finish came as sudden as ers of Wednesday's fight was the surprise with which Shot In Arm In Beating Ray was being ridiculed, by fans it was received. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1942-08-22

'11, 1942 --=:::::::" • -. ~ Seahawks T Cooler 'l'aelde Grea' Lakll/i IOWA-8eattered UumdentonDI Today at I. and cooler today See Stor7 on Pale • THE DAILY IOWAN and tomorrow. Iowa , City'l Morning Newspaper I fIVE CENTS Tal A'.OO~TID ,a188 IOWA CITY', IOWA SATURDAY, AUGUST 22, 1942 '1111 AIBOCIA1'ID ....1 VOLUME XLll NUMBER 284 e e an 5 I In. * * * * * * * * * * *** e*** e 'rlor 111 had Uldton. y, &lid Ilwhlle, Have Qualitalive Tesl A,gainsll eke s Car Fuel Naval, 'Marine Units (arry Oul --leac hes • s, Germany'~ ~~~~.. Besf Ships Delivery Southwest ~nd Pacific Offensive in Monlh i rniles By WALTER CLAV EN uld be LONDON (AP)-The demonstratiorl allied air mast· ---- PEARL H ARBOR (AP)-American ma~ine ~ and naval forces, Jarters Dieppe oj' ery over a chosen zone of operations was fo llowed yesterday by AMERICAN GENERALS IN LONDON DISCUSS IACTIONI with Major Jom s Ro v It, th pr sid nt' . n, participating, oberla, alli ed victory in a qualitative test of Germany's newest and best atr'uck at Japane e forces on Makin island in the northel'n end of opera_ figllting planes against tlle Flyi ng Fortresses of th e United States Move to Ease th Oilb rt islands early thi ' week, Admiral 11. l r W. imitz, Ilrmy a ir forces. Pacific naval commander, said yest rday. 1;tl<\'11 B\\!\'l'n \)1 ill bi.g, four-motored B ~17s were over the North sea Admiral Nimitz said that. the marin s, Rupport d by naval wh n 20 to 25 f Germany's prized Focke-WuU 1908 tackled them. -

BCN 205 Woodland Park No.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 September-October 2011

BCN 205 Woodland Park no.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 september-october 2011 FIRST CLASS MAIL Olde Prints BCN on the web at www.boxingcollectors.com The number on your label is the last issue of your subscription PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.HEAVYWEIGHTCOLLECTIBLES.COM FOR RARE, HARD-TO-FIND BOXING ITEMS SUCH AS, POSTERS, AUTOGRAPHS, VINTAGE PHOTOS, MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS, ETC. WE ARE ALWAYS LOOKING TO PURCHASE UNIQUE ITEMS. PLEASE CONTACT LOU MANFRA AT 718-979-9556 OR EMAIL US AT [email protected] 16 1 JO SPORTS, INC. BOXING SALE Les Wolff, LLC 20 Muhammad Ali Complete Sports Illustrated 35th Anniver- VISIT OUR WEBSITE: sary from 1989 autographed on the cover Muhammad Ali www.josportsinc.com Memorabilia and Cassius Clay underneath. Recent autographs. Beautiful Thousands Of Boxing Items For Sale! autographs. $500 BOXING ITEMS FOR SALE: 21 Muhammad Ali/Ken Norton 9/28/76 MSG Full Unused 1. MUHAMMAD ALI EXHIBITION PROGRAM: 1 Jack Johnson 8”x10” BxW photo autographed while Cham- Ticket to there Fight autographed $750 8/24/1972, Baltimore, VG-EX, RARE-Not Seen Be- pion Rare Boxing pose with PSA and JSA plus LWA letters. 22 Muhammad Ali vs. Lyle Alzado fi ght program for there exhi- fore.$800.00 True one of a kind and only the second one I have ever had in bition fi ght $150 2. ALI-LISTON II PRESS KIT: 5/25/1965, Championship boxing pose. $7,500 23 Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton 9/28/76 Yankee Stadium Rematch, EX.$350.00 2 Jack Johnson 3x5 paper autographed in pencil yours truly program $125 3. -

Boxing Edition

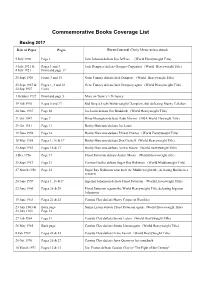

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

In This Corner

Welcome UPCOMING Dear Friends, On behalf of my colleagues, Jerry Patch and Darko Tresnjak, and all of our staff SEA OF and artists, I welcome you to The Old TRANQUILITY Globe for this set of new plays in the Jan 12 - Feb 10, 2008 Cassius Carter Centre Stage and the Old Globe Theatre Old Globe Theatre. OOO Our Co-Artistic Director, Jerry Patch, THE has been closely connected with the development of both In This Corner , an Old Globe- AMERICAN PLAN commissioned script, and Sea of Tranquility , a recent work by our Playwright-in-Residence Feb 23 - Mar 30, 2008 Howard Korder, and we couldn’t be more proud of what you will be seeing. Both plays set Cassius Carter Centre Stage the stage for an exciting 2008, filled with new work, familiar works produced with new insight, and a grand new musical ( Dancing in the Dark ) based on a classic MGM musical OOO from the golden age of Hollywood. DANCING Our team plans to continue to pursue artistic excellence at the level expected of this IN THE DARK institution and build upon the legacy of Jack O’Brien and Craig Noel. I’ve had the joy and (Based on the classic honor of leading the Globe since 2002, and I believe we have been successful in our MGM musical “The Band Wagon”) attempt to broaden what we do, keep the level of work at the highest of standards, and make Mar 4 - April 13, 2008 certain that our finances are healthy enough to support our artistic ambitions. With our Old Globe Theatre Board, we have implemented a $75 million campaign that will not only revitalize our campus but will also provide critical funding for the long-term stability of the Globe for OOO future generations. -

Boxers of the 1940S in This Program, We Will Explore the Charismatic World of Boxing in the 1940S

Men’s Programs – Discussion Boxers of the 1940s In this program, we will explore the charismatic world of boxing in the 1940s. Read about the top fighters of the era, their rivalries, and key bouts, and discuss the history and cultural significance of the sport. Preparation & How-To’s • Print photos of boxers of the 1940s for participants to view or display them on a TV screen. • Print a large-print copy of this discussion activity for participants to follow along with and take with them for further study. • Read the article aloud and encourage participants to ask questions. • Use Discussion Starters to encourage conversation about this topic. • Read the Boxing Trivia Q & A and solicit answers from participants. Boxers of the 1940s Introduction The 1940s were a unique heyday for the sport of boxing, with some iconic boxing greats, momentous bouts, charismatic rivalries, and the introduction of televised matches. There was also a slowdown in boxing during this time due to the effects of World War II. History Humans have fought each other with their fists since the dawn of time, and boxing as a sport has been around nearly as long. Boxing, where two people participate in hand-to-hand combat for sport, began at least several thousand years ago in the ancient Near East. A relief from Sumeria (present-day Iraq) from the third millennium BC shows two facing figures with fists striking each other’s jaws. This is the earliest known depiction of boxing. Similar reliefs and paintings have also been found from the third and second millennium onward elsewhere in the ancient Middle East and Egypt.