University of Cape Coast Testing Practices of Senior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI FACULTY OF RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF AGROFORESTRY FARMERS INDIGENOUS PRACTICES FOR CONSERVING IMPORTANT TREE SPECIES IN THE AFIGYA SEKYERE DISTRICT OF ASHANTI BY IBEL MARK, BED AGRIC (UEW). JUNE, 2009 KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI FACULTY OF RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF AGROFORESTRY FARMERS INDIGENOUS PRACTICES FOR CONSERVING IMPORTANT TREE SPECIES IN THE AFIGYA SEKYERE DISTRICT OF ASHANTI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN AGROFORESTRY BY IBEL MARK BED AGRIC (UEW) JUNE, 2009 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity are complementary phenomena essential to human development. Global awareness of the crisis concerning the conservation of biodiversity is assured following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro. Of equal concern to many world citizens is the uncertain status of the indigenous knowledge that reflects many generations of experience and problem solving by thousands of ethnic groups across the globe (Sutherland, 2003). Very little of this knowledge has been recorded, yet it represents an immensely valuable data base that provides humankind with insights on how numerous communities have interacted with their changing environment including its floral and faunal resources (Emebiri et al., 1995). According to Warren (1992), indigenous knowledge, particularly in the African context, has long been ignored and maligned by outsiders. Today, however, a growing number of African governments and international development agencies are recognizing that local-level knowledge and organizations provide the foundation for participatory approaches to development that are both cost-effective and sustainable. -

Optimal Location of an Additional Hospital in Ejura – Sekyedumase District

OPTIMAL LOCATION OF AN ADDITIONAL HOSPITAL IN EJURA – SEKYEDUMASE DISTRICT (A CONDITIONAL P – MEDIAN PROBLEM) By GYAMERA MICHAEL (BSc. MATHS) A Thesis Submitted To the Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Industrial Mathematics Institute of Distance Learning NOVEMBER 2013 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MSc. and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. GYAMERA MICHAEL PG3013209 ………………….…… ………………………….. Student Name & ID Signature Date Certified by: Mr K. F. Darkwah ………………….…… ………………………….. Supervisor Name Signature Date Certified by: Prof. S. K. Amponsah. ………………….…… ……………………….. Head of Dept. Name Signature Date ii ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses mainly on conditional facility location problems on a network. In this thesis we discuss the conditional p – median problem on a network. Demand nodes are served by the closest facility whether existing or new. The thesis considers the problem of locating a hospital facility (semi – obnoxious facility) as a conditional p – median problem, thus some existing facilities are already located in the district. This thesis uses a new a new formulation algorithm for for the conditional p- median problem on a network which was developed by Oded Berman and Zvi Drezner (2008) to locate an additional hospital in Ejura – Sekyedumase district. A 25 – node network which had four existing hospital was used. -

Sekyere South District Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE SEKYERE SOUTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2015 FISCAL YEAR SEKYERE SOUTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY 1 TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 BACKGROUND………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 DISTRICT ECONOMY……………..………………………………………………………………………………………..4 LOCATION AND SIZE……………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 POPULATION…………………………………………………………………........................................................5 KEY ISSUES………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 VISION………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………….........6 MISSION STATEMENT…………………………………………………………………………………………….……...6 BROAD OBJECTIVES FOR 2015 BUDGET………………………………..…………………………………….....6 STATUS OF 2014 BUDGET IMPLEMENTATION AS AT 30TH JUNE, 2014…………………………….7 DETAILED EXPENDITURE FROM 2014 COMPOSITE BUDGET BY DEPARTMENTS….........10 2014 NON-FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE BY DEPARTMENT AND BY SECTOR……..…………...11 SUMMARY OF COMMITMENTS……………………………………………………………………………………...14 KEY CHALLENGES AND CONSTRAINTS………………………………………………………………………….16 OUTLOOK FOR 2015………………………..…………………………….……………………………………………….16 REVENUE MOBILIZATION STRATEGIES FOR 2015………………………………………………………...17 EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS……………………………………………………….…………………………….18 DETAILED EXPENDITURE FROM 2015 COMPOSITE BUDGET BY DEPARTMENTS………….19 JUSTIFICATION FOR PROJECTS AND PROGRAMMES FOR 2015 & CORRESPONDING COST ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..20 SEKYERE SOUTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY 2 INTRODUCTION Section 92 (3) of the Local Government Act 1993, Act 462 envisages -

Is Home Visiting an Effective Strategy for Improving Family Health: a Case Study in the Sekyere West District

IS HOME VISITING AN EFFECTIVE STRATEGY FOR IMPROVING FAMILY HEALTH: A CASE STUDY IN THE SEKYERE WEST DISTRICT BY DOREEN OSAE-AYENSU (MRS) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL PUBLIC HEALTH, UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTERS OF PUBLIC HEALTH DEGREE SEPTEMBER 2001 ^365756 ■S'37CHS Oct "C; Cj T C o o W ' DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation has been the result of my own field research, except where specific references have been made; and that it has not been submitted towards any degree nor is it being submitted concurrently in candidature for any other degree. ACADEMIC SUPERVISORS: PROF. S. OEOSU-AMAAH MABLDA PAPPOE CANDIDATE; DOREEN OSAE-AYENSU DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear husband, Mr Samuel Osae Ayensu and our children, Kate and Vida. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am most grateful to my academic supervisors, Professor Ofosu-Amaah and Dr. (Mrs) Matilda Pappoe for the direction, support and assistance given me towards this study. This report is a testimony that their efforts have not been in vain. I am also grateful to all the academic staff at the School of Public Health for providing me with knowledge, which helped me at Sekyere West District for the production of this dissertation. To the District Director of Health Services, Dr. Jonathan Adda, the District Health Management Team and all the health workers in the Sekyere West District of the Ashanti Region, I say thank you for making it possible for me to undertake the study in the district. My special thanks also go to Mr. -

Chapter One: Introduction

SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING COMMONWEALTH EXECUTIVE MASTERS IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ASSESSING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES IN MEETING THE CHALLENGES OF LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ASHANTI REGION: - A CASE STUDY OF AFIGYA-KWABRE DISTRICT ASSEMBLY BY STELLA FENIWAAH OWUSU-ADUOMI (MRS.) BA (Hons.) English with Study of Religions. SUPERVISOR MR. E.Y. KWARTENG 2011 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the Commonwealth Executive Masters in Public Administration (CEMPA) and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Stella Feniwaah Owusu-Aduomi (Mrs.) PG3105509 ……………….. ……………….. Student Name ID Signature Date Certified by Name: E.Y. Kwarteng ……………………... ………………. Supervisor Name Signature Date Certified by: Name: Head of Dept. Name Signature Date 2 ABSTRACT Ghana since independence struggled to establish a workable system of local level administration by going through a number of efforts to decentralize political and administrative authority from the centre to the local level. After 30 years, the 1992 constitution and the local government Act 462 of 1993 were promulgated to provide a suitable basis to end Ghana’s struggle for the establishment of an appropriate framework for managing the national development agenda. The formation of the District Assemblies was to provide governance at the local level and help in economic development of the people by formulating and implementing strategic plans to bring about total economic development in their various Districts. -

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF ARCHITECHTURE AND PLANNING (DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING TECHNOLOGY) INVENTORY MANAGEMENT IN THE PUBLIC HOSPITALS: THE CASE OF ANKAASE GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL, AFRANCHO GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL AND MOWIRE FAMILY CARE HOSPITAL ERIC YAW OWUSU (PG9157113) NOVEMBER, 2014 1 KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF ARCHITECHTURE AND PLANNING (DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING TECHNOLOGY) INVENTORY MANAGEMENT IN THE PUBLIC HOSPITALS: THE CASE OF ANKAASE GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL, AFRANCHO GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL AND MOWIRE FAMILY CARE HOSPITAL BY ERIC YAW OWUSU A PROJECT WORK SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING TECHNOLOGY, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF PROCUREMENT MANAGEMENT NOVEMBER, 2014 2 DECLARATION I, Eric Yaw Owusu hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my personal work. Apart from the references cited that have been acknowledged, everything detail in this research are my personal research work. The work has never in part or full been submitted anywhere for the award of any degree anywhere. Eric Yaw Owusu (PG9157113) ..................................... ............................. Student‘s Name Signature Date Mr. Yaw Kush ..................................... ............................. Supervisor Signature Date Professor Joshua Ayarkwa ..................................... ............................. Head of Department Signature Date ii DEDICATION I wish to bless God for His faithfulness. The Lord God has sustained me. I dedicate this masterpiece to my wife Mrs. Victoria Owusu-Rockson and my children, for their love and support throughout the two years I was on the programme. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to God for this privilege. Special thanks go to my Lecturers and supervisor Mr. Yaw Kush and head of department Professor Joshua Ayarkwa for the excellent training and guidance they offered me during the course of study, especially Dr. -

Sekyere South District

SEKYERE SOUTH DISTRICT Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Sekyere South District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

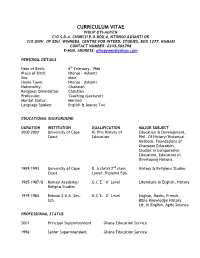

Curriculum Vitae Philip Oti-Agyen C/O S.D.A

CURRICULUM VITAE PHILIP OTI-AGYEN C/O S.D.A. CHURCH P.O.BOX 4, NTONSO ASHANTI OR C/O UNIV. OF EDU. WINNEBA, CENTRE FOR INTERD. STUDIES, BOX 1277, KUMASI CONTACT NUMBER: 0243-506798 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] PERSONAL DETAILS Date of Birth: 6th February, 1966 Place of Birth: Ntonso – Ashanti Sex: Male Home Town: Ntonso – Ashanti Nationality: Ghanaian Religious Orientation: Christian Profession: Teaching (Lecturer) Marital Status: Married Language Spoken: English & Asante Twi EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND DURATION INSTITUTION QUALIFICATION MAJOR SUBJECT 2000-2002 University of Cape M. Phil History of Education & Development, Coast Education Phil. Of History/Historical Methods, Foundations of Ghanaian Education, Studies in Comparative Education, Education in Developing Nations. 1989–1993 University of Cape B. A (Arts) 2nd class History & Religious Studies Coast Lower, Diploma Edu. 1985–1987/8 Kumasi Academy/ G.C.E. ‘A’ Level Literature in English, History Religius Studies 1979-1984 Bekwai S.D.A. Sec. G.C.E. ‘O’ Level English, Maths, French, Sch. Bible Knowledge History Lit, in English, Agric Science PROFESSIONAL STATUS 2001: Principal Superintendent Ghana Education Service 1996: Senior Superintendent Ghana Education Service RESEARCH EXPERIENCE 2003: M. Phil Thesis The Role of the Seventh Day Adventist Church in the Development of Education in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, 1914 – 1966 1993: Under Graduate Long Essay The Role of Religion in the Political Organization of Israel WORKING EXPERIENCE Sept. 2006 to Date: University of Education, Department – Exams Office Winneba – Kumasi 2005 – Date: University of Education, Lecturer, Academic Counsellor Winneba – Kumasi Project Work Co-ordinator 2001 -2002: Uni. Of Cape Coast, Dept. -

Ecology and Development Series No. 15, 2004

Ecology and Development Series No. 15, 2004 Editor-in-Chief: Paul L.G.Vlek Editors: Manfred Denich Christopher Martius Nick van de Giesen Samuel Nii Ardey Codjoe Population and Land Use/Cover Dynamics in the Volta River Basin of Ghana, 1960-2010 Cuvillier Verlag Göttingen To my wonderful wife Akosua Nyantekyewaah and our lovely children, Adjoa, Nii Sersah, Nii Ardey and Nii Baah. ABSTRACT The Volta River basin is one of the most economically deprived areas in Africa. Rain- fed and some irrig ated agriculture is the main economic activity of the majority of the population living in this region. High population growth rates have brought in its wake increasing pressure on land and water resources. Precipitation in the region is characterized by large variability as expressed in periodic droughts. Due to large variability in precipitation patterns, the development and optimum use of (near) surface water resources is the key to improved agricultural production in this region. As a result of the interplay between land/atmosphere, energy, water (vapor) and land use, significant shifts in land use patterns will bring about spatio-temporal changes in weather patterns and rainfall characteristics. There is the need therefore for a sustainable management of the water resources of the Volta River Basin. The Global Change in the Hydrologic Cycle (GLOWA) Volta Project therefore seeks to analyze the physical and socio-economic determinants of hydrological cycles, which will eventually lead to the development of a scientifically sound decision support system for the assessment, sustainable use and development of water resources in the Volta Basin of West Africa. -

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development for Official Use Only

Document of The International Fund for Agricultural Development For Official Use Only REPUBLIC OF GHANA RURAL ENTERPRISES PROJECT (SRS-38-GH) INTERIM EVALUATION Volume I: Main Report & Appendices Report No. 1097 December 2000 Office of Evaluation and Studies RURAL ENTERPRISES PROJECT INTERIM EVALUATION AGREEMENT AT COMPLETION POINT* * The Agreement at Completion Point was prepared in conformity with members of the Core Learning Partnership, viz: Chief Director, Mr. E.P.D. Barnes, Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology; Mr. K Attah-Antwi, Project Coordinator, Rural Enterprises Project; Deputy Director, Mr. K. Okyere , National Development Planning Commission; Mr. M. Manssouri (replacing Mr P. Saint Ange), Country Portfolio Manager, IFAD; Mr. F. Sarassoro, SPMO, UNOPS; and Ms. C. Palmeri, Senior Evaluation Officer, IFAD. In preparation for a possible second phase of the Rural Enterprises Project requested by the Government of Ghana (GOG), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) undertook an Interim Evaluation (IE) of the Project in June - July 2000 using the new IFAD approach to evaluation. A Core Learning Partnership of stakeholders set the objectives and key questions for the IE. The members of the Core Learning Partnership, having reviewed the results of the IE, have come to agreement on the following findings, recommendations and follow-up actions. GENERAL FINDINGS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND AGREED FOLLOW-UP 1. Small-scale enterprise development reduces poverty. New and existing businesses assisted by the Project have contributed to increased economic activity, increased employment and poverty reduction in rural areas. The performance and impact of the Project’s technology and business skills training and counselling programmes to create new businesses and employment demonstrate that they can be used as a model for reducing rural poverty in Ghana. -

Modelling the Intensity of Chemical Control of Capsid Among Cocoa

MODELLING COCOA FARMER BEHAVIOUR CONCERNING THE CHEMICAL CONTROL OF CAPSID IN THE SEKYERE AREA ASHANTI REGION, GHANA by Eric Asare A Thesis submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana in partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY, AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS Faculty of Agriculture College of agribusiness and Natural Resources June, 2011 DECLARATION AND APPROVAL I, Eric Asare, hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the M.Phil degree and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. …………………………………. DATE……………………. ERIC ASARE (STUDENT) CERTIFIED BY: …………………………………… DATE…………………… DR. K. OHENE-YANKYERA (SUPERVISOR) ………………………………………. DATE…………………….. DR. S.C. FIALOR (HEAD OF DEPARTMENT) ii DEDICATION This study is dedicated to the Lord Almighty, from him my help comes from. Secondly, it is dedicated to George Essel, Dorcas Donkor and my entire family. Eric Asare June, 2011 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I thank God for His guidance, grace and steadfast love and for making this Thesis a success. To Dr. Ohene-Yankyera, I say thank you for your patience, fatherly attitude, guidance, and useful and constructive criticisms in making this theses a success. May the good Lord reward you exceedingly abundantly and bless you with more wisdom and mercy so that you can continue to do the good things you have been doing. I am also indebted greatly to the Ghana Sustainable and Cocoa Competitive Systems (SCCS) Project, for their material support. -

Government of Ghana Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development Afigya-Kwabre District Assembly Kodie – Ashanti Draft F

GOVERNMENT OF GHANA MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT AFIGYA-KWABRE DISTRICT ASSEMBLY KODIE – ASHANTI PEACE, UNITY & DEV’T DRAFT FOR DISTRICT MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2014 - 2017) UNDER THE GHANA SHARED GROWTH DEVELOPMENT AGENDA PREPARED BY: AFIGYA-KWABRE DISTRICT ASSEMBLY SEPT. 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page i Table of Content ii List of Tables ix List of Figures xiii List of Acronyms xv Executive Summary xix CHAPTER ONE PERFORMANCE REVIEW AND DISTRICT PROFILE 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1.1.1 The 2009-2013 Medium Term Development Plan 1 1.1.2 Goal of the 2009-2013 Development Plan 1 1.1.3 Objectives of the 2009-2013 Development Plan 2 1.1.4 Status of Implementation of the 2009-2013 Medium Term Plan 3 1.1.5 Statement of Income and Expenditure of the District from 11 2009-2013 1.1.6 Key Problems/Challenges Encountered During the 14 Implementation of the 2010-2013 Plan 1.1.7 Lessons Learnt 15 1.2 DISTRICT PROFILE 16 1.2.1 Location and Size 16 1.2.2 Climate 20 1.2.3 Vegetation 20 2 1.2.4 Relief and Drainage 21 1.2.5 Soils and Geological Formation 23 1.2.6 Conditions of the Natural Environment 26 1.2.7 Conditions of the Built Environment 27 1.2.8 Climate Change Issues 28 1.2.9 Development Implications 28 1.3 DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS 27 1.3.1 Population Size 27 1.3.2 Spatial Distribution of Population 29 1.3.3 Age-Sex Structure 30 1.3.4 Population Density 31 1.3.5 Rural Urban Split 32 1.3.6 Household Characteristics 33 1.3.7 Dependency Ratio 33 1.3.8 Religious Affiliation 33 1.3.9 Migration Trends 33 1.3.10 Culture 34 1.3.11 Labour Force 34 1.4 SPATIAL ANALYSIS 38 1.4.1 Scalogram Analysis 38 1.4.2 Functional Hierarchy of Settlements 41 1.5 Physical Accessibility to Services 41 1.5.1 Accessibility to Health 44 1.5.2 Accessibility to Second Cycle Institutions 46 3 1.5.3 Accessibility to Agriculture Extension Services 48 1.5.4 Accessibility to Banking Services 50 1.5.5.