History of the Chinese Collection at the American Numismatic Society Lyce Jankowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Yen Bloc Before the Second World War

@.PPO8PPTJL ࢎҮ 1.ಕ BOZQSJOUJOH QNBD ȇ ȇ Destined to Fail? The History of the Yen Bloc before the Second World War Woosik Moon The formation of yen bloc did not result in the economic and monetary integration of East Asian economies. Rather it led to the increasing disintegration of East Asian economies. Compared to Japan, Asian regions and countries had to suffer from higher inflation. In fact, the farther the countries were away from Japan, the more their central banks had to print the money and the higher their inflations were. Moreover, the income gap between Japan and other Asian countries widened. It means that the regionalization centered on Japanese yen was destined to fail, suggesting that the Co-prosperity Area was nothing but a strategy of regional dominance, not of regional cooperation. The impact was quite long lasting because it still haunts East Asian countries, contributing to the nourishment of their distrust vis-à-vis Japan, and throws a shadow on the recent monetary and financial cooperation movements in East Asia. This experience highlights the importance of responsible actions on the part of leading countries to boost regional solidarity and cohesion for the viability and sustainability of regional monetary system. 1. Introduction There is now a growing literature that argues for closer monetary and financial cooperation in East Asia, reflecting rising economic and political interdependence between countries in the region. If such a cooperation happens, leading countries should assume corresponding responsibilities. For, the viability of the system depends on their responsible actions to boost regional solidarity and cohesion. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-Hui Li1

The Kyoto Economic Review 74(2): 191–203 (December 2005) The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-hui Li1 1Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University. E-mail: [email protected] The discourses on Taiwanese successful currency reform in postwar period usually put emphasis on the actors of the U.S. economic aids. However, the objective of this research is to re-examine Taiwanese currency reform experiences from the vantage- point of the gold standard during 1949–50. When Kuomintang (KMT) government decided to undertake the currency conversion on June 15, 1949, it was unaided. The inflation was so severe that the KMT government must have used all the resources to finish the inflation immediately and to restore the public confidence in new currency as well as in the government itself. Under such circumstances, the KMT government established a full gold standard based on the gold reserve which the KMT government brought from mainland China in 1949. This research would like to investigate what role the gold standard played during the process of the currency conversion. Where this gold reserve was from? And how much the gold reserve possessed by the KMT government during this period of time? Trying to answer these questions, the research investigates three sources of data: achieves of the KMT government in the period of mainland China, the official re- ports of the KMT government in Taiwan, and the statistics gathered from international organizations. Although the success of Taiwanese currency reform was mostly from the help of U.S. -

The Origin and Evolvement of Chinese Characters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal Czasopism Naukowych (E-Journals) BI WEI THE ORIGIN AND EVOLVEMENT OF CHINESE CHARACTERS Writing, the carrier of culture and the symbol of human civilization, fi rst appeared in Sumer1. Like other ancient languages of Egypt and India, ancient Sumerian symbols have been lost in the process of history, but only Chinese characters still remain in use today. They have played a signifi cant role in the development of Chinese lan- guage and culture. This article intends to display how Chinese characters were creat- ed and how they were simplifi ed from the ancient form of writing to more abstract. Origin of Chinese characters Chinese characters, in their initial forms, were beautiful and appropriately refl ected images in the minds of ancient Chinese that complied with their understanding of reality. Chinese people selected the way of expressing meaning by fi gures and pic- tures, and Chinese characters begun with drawings. Three Myths in Ancient Times It is diffi cult to determine the specifi c time when the Chinese characters emerged. There are three old myths about the origin of Chinese characters. The fi rst refers to the belief that Chinese characters were created by Fu Xi – the fi rst of Three Sovereigns2 in ancient China, who has drew the Eight Trigrams which have evolved into Chinese characters. The mysterious Eight Trigrams3 used for divination are composed of the symbols “–” and “– –”, representing Yang and Yin respectively. 1 I.J. Gelb, Sumerian language, [in:] Encyclopedia Britannica Online, Encyclopedia Britannica, re- trieved 30.07.2011, www.britannica.com. -

The Changing Significance of Latin American Silver in the Chinese Economy, 16Th–19Th Centuries

THE CHANGING SIGNIFICANCE OF LATIN AMERICAN SILVER IN THE CHINESE ECONOMY, 16TH–19TH CENTURIES RICHARD VON GLAHN University of Californiaa ABSTRACT The important role of Chinese demand for silver in stimulating world- wide silver-mining and shaping the first truly global trading system has become commonly recognised in the world history scholarship. The com- mercial dynamism of China during the 16th-19th centuries was integrally related to the importation of foreign silver, initially from Japan but princi- pally from Latin America. Yet the significance of imports of Latin American silver for the Chinese economy changed substantially over these three centuries in tandem with the rhythms of China’s domestic economy as well as the global trading system. This article traces these changes, including the adoption of a new standard money of account— the yuan—derived from the Spanish silver peso coin. Keywords: silver, money supply, peso, coinage, international trade JEL Code: N15, N16 RESUMEN El importante papel de la demanda china de plata para estimular la extracción de plata en todo el mundo y dar forma al primer sistema de comercio verdaderamente global se ha reconocido comúnmente por los a University of California, Los Angeles, History. [email protected] Revista de Historia Económica, Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History 553 Vol. 38, No. 3: 553–585. doi:10.1017/S0212610919000193 © Instituto Figuerola, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Matsuoka, Koji Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1936)

Title CHINA'S CURRENCY REFORM AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE Author(s) Matsuoka, Koji Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1936), 11(1): 75-98 Issue Date 1936-07 URL https://doi.org/10.11179/ker1926.11.75 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 1, Kyoto University Economic Revie-w MEMOIRS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO VOLUME XI 1936 PUBLISHED BY THE DEl'ART)IENT 011' ECONOMIC; IN THE IMPKRIAL UNIVERSITY 011' KYOTO ... ~--.' -~-~,-----.,. ---------_. -'--' " .. ~- ._ .. _--_._ .•.. _-- --------_.-._---_.. _-- CHINA'S CURRENCY REFORM AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE I. INTRODUCTION China, after the commencement of the twentieth century, endeavoured to effect a currency reform, especially through discussions on the problems of treaties, foreign trade and indemnities, but failed to realize its object. The phenomenal rise of the price of silver during the World War seemed to offer an excellent opportunity for effecting this reform, but the opportunity was allowed to slip away. It was in 1929 that Dr. E. W. Kemmerer proposed a currency reform in his .. Project of Law for the Gradual Introduction of a Gold Standard Currency System in China ". After this, the cur rency reform question was neglected for a time, in the midst of the .prevailing world depression, especially that which has corne from the collapse of the gold standard system in many countries. The policy of the United States to purchase silver, put into effect since 1934, has caused the most obvious out flow of silver from China, to the consternation of tbe opti mistic silver men who had never dreamed of such a conse quence, and has thereby intensified the depression of Chinese economy :md given rise to the present currency reform, which may be regarded as a life buoy thrown at Chinese economy adrift in the sea of economic crisis, or as the cul mination of a long-drawn struggle for bringing about the desired currency reform ever since the end of the last cen tury, especially since 1902. -

Wang Guowei, Gu Hongming and Chinese Philosophical Modernity

WANG GUOWEI, GU HONGMING AND CHINESE PHILOSOPHICAL MODERNITY Jinli He Abstract: This paper aims to explore the issue of modernity in Chinese philosophy in the early 20th century. The case study focuses on modern scholar Wang Guowei 王國維 (1877-1927)’s criticism of his contemporary Gu Hongming 辜鴻銘 (1857-1928)’s English translation of the classical Confucian text Zhongyong. I argue that Wang Guowei and Gu Hongming’s case in fact demonstrates two alternative approaches towards philosophical dialogue and cultural exchange. Wang’s approach is a very cultural context-sensitive one: understanding the differences and selecting what is needed for cultural inspiration and reformation—we could call this approach nalaizhuyi 拿來主義 (taking-inism)—borrowing without touching the cultural essence. Gu’s approach is more a songchuzhuyi 送出主義 (sending-outism). It is a global-local context sensitive one: searching for the local’s path towards the global. Reevaluating Gu’s not very exact cultural translation can provide an opportunity to look beyond the “modernization complex,” deconstruct westernization “spell,” and build a new internationalism. I further argue that Gu’s case represents a kind of risky songchuzhuyi and a false internationalism which makes the native culture speak in the other’s terms while Wang’s cultural stand and his “journey” back to his own cultural sensibility sticks to its own terms and discovers the value of the culture. I then further look at Wang Guowei’s ideal of shenshengzhuyi 生生主 義 (live-life-ism) which was originally expressed in his Hongloumeng Pinglun 《红楼梦 评论》(Critique of A Dream of Red Mansions, 1904) and claim that not only can the ideal of shengshengzhuyi explain the underlying reason for an essential turn in Wang’s academic interests from Western philosophy to Chinese history and archaeology, but it can also be applied positively to the contemporary world. -

From Chinese Silver Ingots to the Yuan

From Chinese Silver Ingots to the Yuan With the ascent of the Qing Dynasty in 1644, China's modern age began. This epoch brought foreign hegemony in a double sense: On the one hand the Qing emperors were not Chinese, but belonged to the Manchu people. On the other hand western colonial powers began to influence politics and trade in the Chinese Empire more and more. The colonial era brought a disruption of the Chinese currency history that had hitherto shown a remarkable continuity. Soon, the Chinese money supply was dominated by foreign coins. This was a big change in a country that had used simple copper coins only for more than two thousand years. 1 von 11 www.sunflower.ch Chinese Empire, Qing Dynasty, Sycee Zhong-ding (Boat Shape), Value 10 Tael, 19th Century Denomination: Sycee 10 Tael Mint Authority: Qing Dynasty Mint: Undefined Year of Issue: 1800 Weight (g): 374 Diameter (mm): 68.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation A major characteristic of Chinese currency history is the almost complete absence of precious metals. Copper coins dominated monetary circulation for more than 2000 years. Paper money was invented at an early stage - primarily because the coppers were too unpractical for large transactions. The people's confidence in paper money was limited, however. Hence silver became a common standard of value, primarily in the form of ingots. The use of ingots as means of payment dates back 2000 years. However, because silver ingots were smelted now and again, old specimens are very rare. This silver ingot in the shape of a boat – Yuan Bao in Chinese – dates from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). -

The Circulation of Foreign Silver Coins in Southern Coastal Provinces of China 1790-1890

The Circulation of Foreign Silver Coins in Southern Coastal Provinces of China 1790-1890 GONG Yibing A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in History •The Chinese University of Hong Kong August 2006 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. /y統系位書口 N^� pN 0 fs ?jlj ^^university/M \3V\ubrary SYSTEM^^ Thesis/Assessment Committee Professor David Faure (Chair) Professor So Kee Long (Thesis Supervisor) Professor Cheung Sui Wai (Committee Member) 論文評審委員會 科大衛教授(主席) 蘇基朗教授(論文導師) 張瑞威教授(委員) ABSTRACT This is a study of the monetary history of the Qing dynasty, with its particular attentions on the history of foreign silver coins in the southern coastal provinces, or, Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, from 1790 to 1890. This study is concerned with the influx of foreign silver coins, the spread of their circulation in the Chinese territory, their fulfillment of the monetary functions, and the circulation patterns of the currency in different provinces. China, as a nation, had neither an integrated economy nor a uniform monetary system. When dealing with the Chinese monetary system in whatever temporal or spatial contexts, the regional variations should always be kept in mind. The structure of individual regional monetary market is closely related to the distinct regional demand for metallic currencies, the features of regional economies, the attitudes of local governments toward certain kinds of currencies, the proclivities of local people to metallic money of certain conditions, etc. -

Oxford University Press. No Part of This Book May Be Distributed, Posted, Or

xix Gaining Currency xx 1 CHAPTER 1 A Historical Prologue At the end of the day’s journey, you reach a considerable town named Pau- ghin. The inhabitants worship idols, burn their dead, use paper money, and are the subjects of the grand khan. The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, Marco Polo uch was the strange behavior of the denizens of China in the Sthirteenth century, as narrated by Marco Polo. Clearly, using paper money was a distinguishing characteristic of the peoples the famed itinerant encountered during his extensive travels in China, one the explorer equated with what Europeans would have regarded as pagan rituals. Indeed, the notion of using paper money was cause for wonderment among Europeans at the time and for centuries thereafter; paper money came into use in Europe only during the seventeenth century, long after its advent in China. That China pioneered the use of paper money is only logical since paper itself was invented there during the Han dynasty (206 BC– 220 AD). Cai Lun, a eunuch who entered the service of the imperial palace and eventually rose to the rank of chief eunuch, is credited with the invention around the year 105 AD. Some sources indicate that paper had been invented earlier in the Han dynasty, but Cai Lun’s achievement was the development of a technique that made the mass production of paper possible. This discovery was not the only paper- making accomplishment to come out of China; woodblock printing and, subsequently, 2 movable type that facilitated typography and predated the Gutenberg printing press by about four centuries can also be traced back there. -

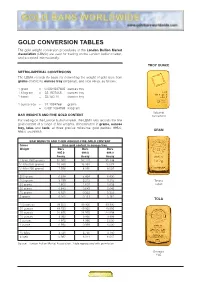

Gold Conversion Tables

GOLD CONVERSION TABLES The gold weight conversion procedures of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) are used for trading on the London bullion market, and accepted internationally. TROY OUNCE METRIC-IMPERIAL CONVERSIONS The LBMA records its basis for converting the weight of gold bars from grams (metric) to ounces troy (imperial), and vice versa, as follows: 1 gram = 0.0321507465 ounces troy 1 kilogram = 32.1507465 ounces troy 1 tonne = 32,150.70 ounces troy 1 ounce troy = 31.1034768 grams = 0.0311034768 kilogram Valcambi BAR WEIGHTS AND FINE GOLD CONTENT Switzerland For trading on the London bullion market, the LBMA also records the fine gold content of a range of bar weights, denominated in grams, ounces troy, tolas and taels, at three precise millesimal gold purities: 995.0, GRAM 999.0 and 999.9. BAR WEIGHTS AND THEIR AGREED FINE GOLD CONTENT Gross Fine gold content in ounces troy Weight Bars Bars Bars 995.0 999.0 999.9 Assay Assay Assay 1 kilo (1000 grams) 31.990 32.119 32.148 1/2 kilo (500 grams) 15.995 16.059 16.074 1/4 kilo (250 grams) 7.998 8.030 8.037 200 grams 6.398 6.424 6.430 100 grams 3.199 3.212 3.215 Tanaka 50 grams 1.600 1.607 1.608 Japan 20 grams 0.640 0.643 0.643 10 grams 0.321 0.322 0.322 5 grams 0.161 0.161 0.161 TOLA 100 ounces 99.500 99.900 99.990 50 ounces 49.750 49.950 49.995 25 ounces 24.875 24.975 24.998 10 ounces 9.950 9.990 9.999 5 ounces 4.975 4.995 5.000 1 ounce 0.995 0.999 1.000 10 tolas 3.731 3.746 3.750 5 taels 5.987 6.011 6.017 Source: London Bullion Market Association. -

Power, Identity and Antiquarian Approaches in Modern Chinese Art

Power, identity and antiquarian approaches in modern Chinese art Chia-Ling Yang Within China, nationalistic sentiments notably inhibit objective analysis of Sino- Japanese and Sino-Western cultural exchanges during the end of the Qing dynasty and throughout the Republican period: the fact that China was occupied by external and internal powers, including foreign countries and Chinese warlords, ensured that China at this time was not governed or united by one political body. The contemporary concept of ‘China’ as ‘one nation’ has been subject to debate, and as such, it is also difficult to define what the term ‘Chinese painting’ means.1 The term, guohua 國畫 or maobihua 毛筆畫 (brush painting) has traditionally been translated as ‘Chinese national painting’. 2 While investigating the formation of the concept of guohua, one might question what guo 國 actually means in the context of guohua. It could refer to ‘Nationalist painting’ as in the Nationalist Party, Guomindang 國民黨, which was in power in early 20th century China. It could also be translated as ‘Republican painting’, named after minguo 民國 (Republic of China). These political sentiments had a direct impact on guoxue 國學 (National Learning) and guocui 國粹 (National Essence), textual evidence and antiquarian studies on the development of Chinese history and art history. With great concern over the direction that modern Chinese painting should take, many prolific artists and intellectuals sought inspiration from jinshixue 金石學 (metal and stone studies/epigraphy) as a way to revitalise the Chinese