Chinese Silver Ingots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 China: Government Policy and Tourism Development

China: Government Policy 4 and Tourism Development Trevor H. B. Sofield Introduction In 2015, according to the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA), China welcomed 133.8 million inbound visitors; it witnessed 130 million outbound trips by its citizens; and more than 4 billion Chinese residents took domestic trips around the country. International arrivals generated almost US$60 billion, outbound tour- ists from China spent an estimated US$229 billion (GfK, 2016), and domestic tour- ism generated ¥(Yuan)3.3 trillion or US$491 billion (CNTA, 2016). By 2020, Beijing anticipates that domestic tourists will spend ¥5.5 trillion yuan a year, more than double the total in 2013, to account for 5 percent of the country’s GDP. In 2014, the combined contribution from all three components of the tourism industry to GDP, covering direct and indirect expenditure and investment, in China was ¥5.8 trillion (US$863 billion), comprising 9.4% of GDP. Government forecasts suggest this figure will rise to ¥11.4 trillion (US$1.7 trillion) by 2025, accounting for 10.3% of GDP (Wang et al., 2016). Few governments in the world have approached tourism development with the same degree of control and coordination as China, and certainly not with outcomes numbering visitation and visitor expenditure in the billions in such a short period of time. In 1949 when Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CCP) achieved complete control over mainland China, his government effectively banned all domestic tourism by making internal movement around the country illegal (CPC officials excepted), tourism development was removed from the package of accept- able development streams as a bourgeoisie activity, and international visitation was a diplomatic tool to showcase the Communist Party’s achievements, that was restricted to a relative handful of ‘friends of China’. -

The History of the Yen Bloc Before the Second World War

@.PPO8PPTJL ࢎҮ 1.ಕ BOZQSJOUJOH QNBD ȇ ȇ Destined to Fail? The History of the Yen Bloc before the Second World War Woosik Moon The formation of yen bloc did not result in the economic and monetary integration of East Asian economies. Rather it led to the increasing disintegration of East Asian economies. Compared to Japan, Asian regions and countries had to suffer from higher inflation. In fact, the farther the countries were away from Japan, the more their central banks had to print the money and the higher their inflations were. Moreover, the income gap between Japan and other Asian countries widened. It means that the regionalization centered on Japanese yen was destined to fail, suggesting that the Co-prosperity Area was nothing but a strategy of regional dominance, not of regional cooperation. The impact was quite long lasting because it still haunts East Asian countries, contributing to the nourishment of their distrust vis-à-vis Japan, and throws a shadow on the recent monetary and financial cooperation movements in East Asia. This experience highlights the importance of responsible actions on the part of leading countries to boost regional solidarity and cohesion for the viability and sustainability of regional monetary system. 1. Introduction There is now a growing literature that argues for closer monetary and financial cooperation in East Asia, reflecting rising economic and political interdependence between countries in the region. If such a cooperation happens, leading countries should assume corresponding responsibilities. For, the viability of the system depends on their responsible actions to boost regional solidarity and cohesion. -

The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’S Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications

The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications Mahima Duggal ASIA PAPER June 2021 The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications Mahima Duggal © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications” is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. © ISDP, 2021 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-21-4 Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. +46-841056953; Fax. +46-86403370 Email: [email protected] Editorial correspondence should be directed to the address provided above (preferably by email). Contents Summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................... -

The Digital Yuan and China's Potential Financial Revolution

JULY 2020 The digital Yuan and China’s potential financial revolution: A primer on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) BY STEWART PATERSON RESEARCH FELLOW, HINRICH FOUNDATION Contents FOREWORD 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WHAT IS IT AND WHAT COULD IT BECOME? 5 THE EFFICACY AND SCOPE OF STABILIZATION POLICY 7 CHINA’S FISCAL SYSTEM AND TAXATION 9 CHINA AND CREDIT AND THE BANKING SYSTEM 11 SEIGNIORAGE 12 INTERNATIONAL AND TRADE RAMIFICATIONS 13 CONCLUSIONS 16 RESEARCHER BIO: STEWART PATERSON 17 THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 2 Foreword China is leading the way among major economies in trialing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). Given China’s technological ability and the speed of adoption of new payment methods by Chinese consumers, we should not be surprised if the CBDC takes off in a major way, displacing physical cash in the economy over the next few years. The power that this gives to the state is enormous, both in terms of law enforcement, and potentially, in improving economic management through avenues such as surveillance of the shadow banking system, fiscal tax raising power, and more efficient pass through of monetary policy. A CBDC has the potential to transform the efficacy of state involvement in economic management and widens the scope of potential state economic action. This paper explains how a CBDC could operate domestically; specifically, the impact it could have on the Chinese economy and society. It also looks at the possible international implications for trade and geopolitics. THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. -

China's Currency Policy

Updated May 24, 2019 China’s Currency Policy China’s policy of intervening in currency markets to control The yuan-dollar exchange rate has experienced volatility the value of its currency, the renminbi (RMB), against the over the past few years. On August 11, 2015, the Chinese U.S. dollar and other currencies has been of concern for central bank announced that the daily RMB central parity many in Congress over the past decade or so. Some rate would become more “market-oriented,” However, over Members charge that China “manipulates” its currency in the next three days, the RMB depreciated by 4.4% against order to make its exports significantly less expensive, and the dollar and it continued to decline against the dollar its imports more expensive, than would occur if the RMB throughout the rest of 2015 and into 2016. From August were a freely traded currency. Some argue that China’s 2015 to December 2016, the RMB fell by 8.8% against the “undervalued currency” has been a major contributor to the dollar. From January to December 2017, the RMB rose by large annual U.S. merchandise trade deficits with China 4.6% against the dollar. (which totaled $419 billion in 2018) and the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs. Legislation aimed at addressing Since 2018, the RMB’s value against the dollar has “undervalued” or “misaligned” currencies has been generally trended downward. Many economists contend introduced in several congressional sessions. On May 23, that the RMB’s recent decline has largely been caused by 2019, the U.S. -

On the Renminbi

Revised September 2005 On the Renminbi Jeffrey Frankel Harpel Professor for Capital Formation and Growth Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University CESifo Forum, vol 6, no. 3, Autumn 2005, p. 16-21 Ifo Institute for Economic Research Fixed and flexible exchange rates each have advantages, and a country has the right to choose the regime suited to its circumstances. Nevertheless, several arguments support the view that China should allow its currency to appreciate. (1) China’s economy in 2004 was on the overheating side of internal balance, and appreciation would help easy inflationary pressure. Although this excess demand probably moderated in 2005, the general principle remains: to achieve both internal balance and external balance simultaneously, an economy needs to be able to adjust its real exchange rate as well as its level of spending. (2) Although foreign exchange reserves are a useful shield against currency crises, by now China’s current level is fully adequate, and US treasury securities do not pay a high return. (3) It becomes increasingly difficult to sterilize the inflow over time. (4) Although external balance could be achieved by increasing expenditure, this policy applied by itself might send China back into the inflationary zone of excess demand. (5) A large economy like China can achieve adjustment in the real exchange rate via flexibility in the nominal exchange rate more easily than via price flexibility. (6) The experience of other emerging markets points toward exiting from a peg when times are good and the currency is strong, rather than waiting until times are bad and the currency is under attack. -

The Analysis of the Current Situation and Prospects for Tourism Real Estate in China LIU Lijun , WANG Jing2 , HE Yuanyuan3

2nd International Conference on Science and Social Research (ICSSR 2013) The Analysis of the Current Situation and Prospects for Tourism Real Estate in China LIU Lijun1, a, WANG Jing 2 , HE Yuanyuan 3 Economic and Trade Institute, Shijiazhuang university of economics, P.R. China, 050031 Shijiazhuang University of economics, P.R. China, 050031 Shijiazhuang institute of railway technology ,P.R. China, 050000 a E-mail [email protected] Keywords: Real-estate for tourism. Development. Real-estate. Environment. Abstract . Real-estate for tourism is an extension of timeshare in China market. The real estate and tourism initiative created this new format in terms of economic growth an environmental change. Real-estate for tourism in China has undergone more than two decades of development, in the great achievements made at the same time exposed a lot of problems: Which one is the focus of real-estate for tourism between tourism in and real estate? Is it a simple superposition of the tourism and real estate? What is the difference between this new form of real estate and other property? Taking the advantage of the combinations of theory and practice, quality study and quantity analysis, data collection and field research, this paper gives answers to these questions through analysis of the development of real-estate for tourism in China market. Introduction The early nineteen eighties, tourism industry began to develop in China, especially since the end of last century, the tourism industry as “sunrise industry" by the national advocate energetically, become the new period in our country and a new growth point of national economy. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

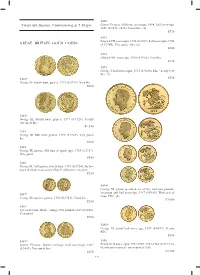

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-Hui Li1

The Kyoto Economic Review 74(2): 191–203 (December 2005) The Currency Conversion in Postwar Taiwan: Gold Standard from 1949 to 1950 Shih-hui Li1 1Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University. E-mail: [email protected] The discourses on Taiwanese successful currency reform in postwar period usually put emphasis on the actors of the U.S. economic aids. However, the objective of this research is to re-examine Taiwanese currency reform experiences from the vantage- point of the gold standard during 1949–50. When Kuomintang (KMT) government decided to undertake the currency conversion on June 15, 1949, it was unaided. The inflation was so severe that the KMT government must have used all the resources to finish the inflation immediately and to restore the public confidence in new currency as well as in the government itself. Under such circumstances, the KMT government established a full gold standard based on the gold reserve which the KMT government brought from mainland China in 1949. This research would like to investigate what role the gold standard played during the process of the currency conversion. Where this gold reserve was from? And how much the gold reserve possessed by the KMT government during this period of time? Trying to answer these questions, the research investigates three sources of data: achieves of the KMT government in the period of mainland China, the official re- ports of the KMT government in Taiwan, and the statistics gathered from international organizations. Although the success of Taiwanese currency reform was mostly from the help of U.S.