Baseball As the Bleachers Like It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1966-10-22

Nancy Moore -Is New Miss U Of I By KATHY FERRY Following the last entry in the parade, StaH Writer pectators left the reviewing stand area Everyone was eXcited Friday night, but at Clinton Street and Iowa Avenue to move then there was Nancy Moore. closer to the east steps of Old Capitol, I The young. the old, University students, where the pep raUy and the Miss U of I Homecoming faculty and alumni who came from far coronation took place. and near to attend Homecoming '66, all Max Hawkins, alumni record oWce, was shivl'red in th October night air as Mi master of ceremonie . Nancy MOtIre. 3. Homewood, Ill., wa After several cheef5 led by the band Events Today crowned Ii o( I. and the cheerleaders, Athletic Director Th(' crowning ceremonies (oUowed an Fore I Eva hevslli and Coach Ray Nagel Alumni eoUce Hours : hour long parade through downtown Iowa addr ed the crowd. Alpha K.ppa PII, Business Administra· City. Repre entaUv from the various hous· tion. 10 a.m. - noon. Harvard Room, IMU Float Sweepstakes honors went to Wright ing units spon oring award winning Ooats Dent.I Hygl.ne, H1 a.m., Princeton House and Quadrangle bousing units won were asked to come (orward and were pre· Room, IMU the weeps takes award (or their fioat. sented tropbies. Dentistry, 9-11 a.m., Princeton Room, " coopy Dreams On." The fioat carried the FloatWilllllrl IMU comic strip character Snoopy dreaming Housing unit noat winners. sponsors and Educltion, 9:30-11 a.m., Engineering about an Iowa victory over Nortbwestern themes are: Pi Beta Phi. -

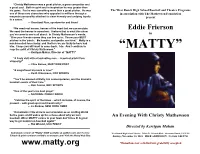

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

The History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 9 Marq

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 9 Article 7 Issue 2 Spring Before the Flood: The iH story of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption Roger I. Abrams Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Roger I. Abrams, Before the Flood: The History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 9 Marq. Sports L. J. 307 (1999) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol9/iss2/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMPOSIUM: THE CURT FLOOD ACT BEFORE THE FLOOD: THE HISTORY OF BASEBALL'S ANTITRUST EXEMPTION ROGER I. ABRAMS* "I want to thank you for making this day necessary" -Yogi Berra on Yogi Berra Fan Appreciation Day in St. Louis (1947) As we celebrate the enactment of the Curt Flood Act of 1998 in this festschrift, we should not forget the lessons to be learned from the legal events which made this watershed legislation necessary. Baseball is a game for the ages, and the Supreme Court's decisions exempting the baseball business from the nation's antitrust laws are archaic reminders of judicial decision making at its arthritic worst. However, the opinions are marvelous teaching tools for inchoate lawyers who will administer the justice system for many legal seasons to come. The new federal stat- ute does nothing to erase this judicial embarrassment, except, of course, to overrule a remarkable line of cases: Federal Baseball,' Toolson,2 and Flood? I. -

Anatomy of an Aberration: an Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball Through Flood V

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 2 Spring 2008 Article 2 Anatomy of an Aberration: An Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball through Flood v. Kuhn (1972) David L. Snyder Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation David L. Snyder, Anatomy of an Aberration: An Examination of the Attempts to Apply Antitrust Law to Major League Baseball through Flood v. Kuhn (1972), 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 177 (2008) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANATOMY OF AN ABERRATION: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ATTEMPTS TO APPLY ANTIRUST LAW TO MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL THROUGH FLOOD V. KUHN (1972) David L. Snyder* I. INTRODUCTION The notion that baseball has always been exempt from antitrust laws is a commonly accepted postulate in sports law. This historical overview traces the attempts to apply antitrust law to professional baseball from the development of antitrust law and the reserve system in baseball in the late 1800s, through the lineage of cases in the Twen- tieth Century, ending with Flood v. Kuhn in 1972.1 A thorough exam- ination of the case history suggests that baseball's so-called antitrust "exemption" actually arose from a complete misreading of the Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Phone: (718) 579-4460 • E-mail: [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr & @losyankeespr World Series Champions: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2014 (2013) New York Yankees (76-72) at TAMPA BAY RAYS (72-78) Standing in AL East: .............3rd, -12.5 LHP Chris Capuano (2-3, 4.90) vs. RHP Alex Colome (1-0, 2.79) Games Behind for Second WC ....... -5.0 Current Streak: .....................Lost 1 Monday, September 15, 2014 • Tropicana Field • 7:10 p.m. ET Home Record: .............38-35 (46-35) Road Record:. 38-37 (44-37) Game #149 • Road Game #76 • TV: YES/MLBN • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM Day Record: ................30-21 (32-24) Night Record: ..............46-51 (53-53) Pre-All-Star .................47-47 (51-44) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the first game of EQUAL SANDMAN: With 2K in Sunday’s loss at Baltimore, Post-All-Star ................29-25 (34-33) a three-game series at Tampa Bay… is also the fifth game RHP Dellin Betances has 130K this season (in 86.2IP), tying vs. AL East: ................. 29-33 (37-39) of a seven-game road trip that also included four games Mariano Rivera (130K in 107.2IP in 1996) for the most single- vs. AL Central: .............. 19-16 (22-11) at Baltimore (went 1-3)… went 5-4 on their nine-game season strikeouts by a Yankees reliever… it is also tied for the vs. -

Records Reveal Queer Ceremony

ST. CHARLES HERALD. HAHN VILLE. LOUISIANA. EMSUE IN ÏMé TIMELY HITTING AND SPLENDID WORK OF IDLE WORKMEN PARADING IN BUDAPEST PITCHERS HAVE KEPT GIANTS IN FRONT Umpire Bob Emslie was the victim of a peculiar pla'y at fin- X: cinnati recently, when a hard throw from Mefkle hit him on r ' ’ ' ■ ; the wrist and painfully injured him. Daubert had tripled to -, j*-«? h the score board and Merkle ran p ? out into center field and took P a sk e rt’s throw . .Take stopped at third, but Merkle threw to ward the plate with all his force. Umpire Emslie, seeing Dau- bert stop at third, was backing away into the diamond when the line throw hit him on the mMzÆï left wrist. The injury was so annoying that the game was de layed for several minutes while many of the athletes urged the veteran official to leave his post and let Bill Klem handle the ^'J\yyvAjYAGtr/^ game alone. mm W&sC/aH/ff1?G#AW Bob, however, refused to do so and remained on the job for the entire afternoon, though hik bruised wrist was giving him One of the huge parades of idle workmen that murk the rule of the com m unists in Budapest, the capital of Hun constant pain. He received the g a r y . unusual compliment of a round of applause from the fans when it was seen that he was going to or in the territory which is now sa stick to his work. known. \ y s j j Records Reveal Practice Died Before Revolution. -

! Join Arf's Pet Walk !

People rescuing animals...Animals rescuing people® ◆ 925.256.1ARF ◆ www.arf.net ◆ Spring 2012 ANIMALS ON BROADWAY PET WALK Sunday, May 20, Broadway Plaza Walnut Creek arly in the morning the air is thick with excitement as the Ecrowd gathers. Families, friends, neighbors, co-workers and their four- legged companions are all together waiting for the start of ARF’s Pet Walk. THE RACE IS ON! JOIN ARF’S PET WALK TO RAISE $75,000 TO RESCUE MORE ANIMALS! The anticipation is seen in their faces, and Walk as an individual or in a forget to email and Facebook your their furry pals seem to sense something Pack of three or more. Start collecting friends a link to your page. Can’t join big is going to happen. In costumes or pledges today with your own easy-to- the celebration in person? You can happily strolling on leashes, hundreds create fundraising webpage and earn still help — create your personalized of dogs and even a few kitties join their “treats” while raising money to help webpage for a virtual walk! human families for a one mile fundraising abandoned animals. Make your page REGISTER TODAY AT ARF.NET walk around Broadway Plaza to raise fun and unique by adding photos, HAVE QUESTIONS? money for ARF to save more lives. videos and your personal story. Don’t EMAIL [email protected] STAY AND PLAY AT ANIMALS ON BROADWAY Pet Walk 10:30 a.m. sharp Community Event 11-4 p.m. Follow your passion for pets to the 12th annual Animals on Broadway! Join ARF and for the ultimate celebration of the special bond we share with our furry friends at this spectacular free community event immediately after the Pet Walk. -

Vs. KANSAS CITY ROYALS (31-71) Standing in AL East

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION YANKEE STADIUM • ONE EAST 161ST STREET • BRONX, NY 10451 PHONE: (718) 579-4460 • E-MAIL: [email protected] • SOCIAL MEDIA: @YankeesPR & @LosYankeesPR WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2018 (2017) NEW YORK YANKEES (65-36) vs. KANSAS CITY ROYALS (31-71) Standing in AL East: ..........2nd, -5.0G Current Streak: ...................Won 1 Split-Admission Doubleheader • Saturday, July 28, 2018 • Yankee Stadium Current Homestand. 1-0 Game 1 (1:05 p.m.): RHP Luis Severino (14-3, 2.63) vs. RHP Brad Keller (3-4, 3.20) Recent Road Trip .................... 1-2 Home Record: .............35-14 (51-30) Game #102 • Home Game #50 • TV: WPIX • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Road Record: ..............30-22 (40-41) Game 2 (7:05 p.m.): LHP CC Sabathia (6-4, 3.51) vs. RHP Heath Fillmyer (0-1, 2.82) Day Record: ................22-9 (34-27) Night Record: .............43-27 (57-44) Game #103 • Home Game #51 • TV: YES • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Pre-All-Star ................62-33 (45-41) Post-All-Star ..................3-3 (46-30) vs. AL East: ................25-19 (44-32) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play a split-admission LET'S PLAY TWO: Today is the Yankees' third doubleheader vs. AL Central: ..............14-4 (18-15) doubleheader today vs. Kansas City… are 1-0 on their six- of the season, matching their total from 2017… have split vs. -

First- See NASH

Baseball Club Owners Disagree On Later Opening ONE RUN MARGINS “Pavlowa” Cochrane Does His Stuff STICK’S BOWLERS Boston Moguls Favor WIN TELEPHONE How It's Done In DECIDED MAJOR Idea; Weil, . LEAGUE TITLE Heydler Dear Old Newark GAMES YESTERDAY it By DAM PARKER Cards Come Behind 8 to 7 Flammia Takes High Sin- Harridge Against / Count in Last Inning— gle, Anderson High Three and White A partial poll of major league club presidents indicates Cobs Edge Out Reds— High that the base- <*>»»mwm««»M**M****»»M****l*>*>**,**>M*>*t**M***,*t*>***’ fair support for John A. Heydler’s suggestion Manush Hero Again Average ball season be opened and closed later because of weather THE FROST BEING oil the pumpkin to such a depth at the local that all ball -were called conditions. apple orchards Wednesday afternoon games JACK CUDDY Gay Steck'a bowlers captured the a bunch of the boys decided to go over to the Yankees’ new farm The National League president oft, Press Staff Correspondent) 1932 In the Southern New in Newark and observe with what frills and furbelows a baseball sea- (United bunting at Cincinnati New York, April 14-r(UP)— made his suggestion Is In the International League. After having shivered England Telephone duckpln league son opened The champion Cardinals have yesterday. His proposal was op- iciest hours he has In since he Dr was climaxed last Friday through three of the put accompanied started after the National league which William and what not to a over Pep- posed Immediately by Cook to the Pole, your purveyor of news, gossip begs again. -

The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game Online

jRKFJ [Mobile pdf] The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game Online [jRKFJ.ebook] The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game Pdf Free Donald Dewey, Nicholas Acocella ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF #3435217 in Books Dewey Donald 2016-05-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.02 x 1.01 x 5.98l, .0 #File Name: 0803299397456 pagesThe Black Prince of Baseball Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game | File size: 49.Mb Donald Dewey, Nicholas Acocella : The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Rogue of the DiamondBy Bud O'BaerHal Chase was a slick-fielding first baseman whose fielding impressed the men and whose looks impressed the women. Babe Ruth selected Chase as his first baseman for his all-time baseball team. However, the fast-living liked to make an easy buck by throwing games to win money by betting against his team. Essentially Hal's MLB career was over by 1920 when judge Landis began to clean-up the game by expelling the notorious Black Sox and other known gamblers. Hal Chase was a man who lived by the produce of his glove and his bat, so he went on to play many additional years in outlaw leagues, down in Mexico and even in the semi-professional ranks.