Diamond Justice—Teaching Baseball and the Law Edmund P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REATH Sudden

Cochrane Shows His BUFFS DEFEAT _Bmincu Service! , Rental! sudden 8 Travel Opportunities REATH 34 Insurance Boys How It’s Done 63 Apartment! ■ FOR ‘ORIOLE’ PADRES 11-5 McAllen • THREE ROOM soetbeesi -pert- Reynosa INSURANCE inent. 1522 West St. Charles (By Associated Press) m a ten-inning struggle and gave one of the longest leads BONDS Cochrane not only has the Tigers BUS _A-U Mickey this 2 A ah Hillin Fails In Bid Itiovid Leader Suffers they have enjoyed season. DAILY SCHEDULE ROOMS—-Apartment* two Modus turned out to be a line Inspirational over the second 1-2 games place For 23rd Win Of from office. 1006 St. Hemorrhage After leader erho has piloted the Detroit Leaves Leans W. B. CLINT post Charles, Yankees. B-30 into the American league Season McAllen Phene 194 W. Tigers Going into the tenth at 6-6, BUI Reynosa Phone 6 lead, but if the occasion demands with .... 1:30 a m. 110 a a Rogell started things a single. SETHMAN oom- the actual Apartment*.OsL it “Mike" can do a lot of Hank Greenberg sacrificed and (By tha Associated Press) 10:00 a m. 9:00 a m. — foruhle, furnished apartment. MBaTLANTA Aug. 9 14b That work of ball games. 42:00 11:00 a a winning Marvin Owen walked. That brought Manager Carey Selph’a sixth pm. Phone 1331230 >ld Oriole. Wilbert Robin- Cochrane demonstrated that Wed- Cochrane and he a the 2:00 p. m. 1:00 p nx up smacked Houston Buffaloes ware full Max*? Baer, heavyweight when he struck the blow place 6:00 pm.' 5:00 m. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

Phillies Legend Remembered As

C4 | Tuesday, December 8, 2020 |beaumontenterprise.com |BeaumontEnterprise SPORTS DICK ALLEN: 1942-2020 Phillies legendrememberedas‘courageouswarrior’ By RobMaaddi parkevery dayand just play were 56-106 and only AP SPORTS WRITER baseball.” 495,000 people came out Allen wasMiddleton’sfa- to Comiskey Parktosee DickAllen hitthe ballso vorite player as akid. He them. hard, fans in Philadelphia called the abuseAllenre- “It wasone of those startedshowing up in bat- ceived“horrific” and point- things wherethe fans were ting practice during his ed outhis accomplish- kind of down in the rookieseasonjusttowatch ments areevengreatercon- dumps,”Bill Melton, hisAll- him hammer shots overthe sidering the racism he en- Star teammate in Chicago, Coca-Cola sign atopthe left- dured. recalled Monday. “Things center field roof at Connie Allen batted .292 with 351 were bad. The economy Mack Stadium. home runs, 1,119RBIs and wasbad,everything.” The rousing attention, he .912 OPSin15seasons.He “I think Dick just brought gotthatearly.The rightful playedfirst base, thirdbase aflavortothe WhiteSox. acclaim,sadly,hehad to and left field. And the flavorwas this: na- wait much longer. Afterseven years in Phil- tional attention. We’d go in- Allen, aseven-timeAll- adelphia, Allen playeda to NewYork, we’d finally Star sluggerwhose fight season each with the Cardi- getwriters,press, pictures against racism duringatu- nals and Dodgers. back to Chicago. …Wewere multuoustime with the In 1972, he joined the starting to draw attention, Philliesinthe 1960scost WhiteSox andwas an im- magazine covers,”hesaid. him on and off the field, mediate hitinwinningthe Melton said Allen would died Monday.Hewas 78. AL MVP.Allen led the AL in always shrug off theHall of The 1964 NL Rookie of Matt Slocum /AssociatedPress homers(37), RBIs (113), on- Fame vote,sayingitwasn’t Year and1972 AL MVP hada Former Philadelphia Phillies greatDickAllen, pictured in 2017,aseven-time base averageand slugging meant to be. -

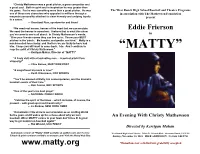

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

The Jurisprudence of the Infield Fly Rule

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Summer 2004 Taking Pop-Ups Seriously: The urJ isprudence of the Infield lF y Rule Neil B. Cohen Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] S. W. Waller Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Common Law Commons, Other Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation 82 Wash. U. L. Q. 453 (2004) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. TAKING POP-UPS SERIOUSLY: THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE INFIELD FLY RULE NEIL B. COHEN* SPENCER WEBER WALLER** In 1975, the University of Pennsylvania published a remarkable item. Rather than being deemed an article, note, or comment, it was classified as an "Aside." The item was of course, The Common Law Origins of the Infield Fly Rule.' This piece of legal scholarship was remarkable in numerous ways. First, it was published anonymously and the author's identity was not known publicly for decades. 2 Second, it was genuinely funny, perhaps one of the funniest pieces of true scholarship in a field dominated mostly by turgid prose and ineffective attempts at humor by way of cutesy titles or bad puns. Third, it was short and to the point' in a field in which a reader new to law reviews would assume that authors are paid by the word or footnote. Fourth, the article was learned and actually about something-how baseball's infield fly rule4 is consistent with, and an example of, the common law processes of rule creation and legal reasoning in the Anglo-American tradition. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football Natalie M

Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 8 9-1-1995 Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football Natalie M. Gurdak Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tjcil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Natalie M. Gurdak, Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Strikes: How Baseball Could Have Avoided Their Latest Strike by Studying Sports Law from British Football, 3 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int'l L. 121 (1995). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tjcil/vol3/iss1/8 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact daniel- [email protected]. BASEBALL, HOT DOGS, APPLE PIE, AND STRIKES: HOW BASEBALL COULD HAVE AVOIDED THEIR LATEST STRIKE BY STUDYING SPORTS LAW FROM BRITISH FOOTBALL I. INTRODUCTION At the end of the 1994 Major League Baseball Season, the New York Yankees and the Montreal Expos had the best records in the American and National Leagues, respectively.' However, neither team made it to the World Series.2 Impossible, you say? Not during the 1994 season, which ended abruptly in August due to a players' strike.' As the players and owners disputed over financial matters, fans were deprived of a World Series for the second time in the history of the game.4 America's favorite pastime was in peril. -

Hall of a Debate

Hall of a debate Ron Santo fell nine votes short in his latest Hall of Fame bid. In Chicago, Ron Santo is a Hall of Famer beyond most reasonable doubts. So what do some in the Veterans Committee see in his career that others do not? By Paul Ladewski Posted on Friday, December 12th Ask even a lukewarm Cubs fan if Ron Santo deserves to be in the Hall of Fame, and chances are he'll treat you like an alien from a land far, far away. Three-hundred-forty-two home runs. Nine All-Star Game appearances. Five Gold Glove Awards. By almost any statistical measure, he ranks on the short list of best third baseman of his time. How can Ron Santo not be a Hall of Famer? That the Veterans Committee closed the door on Santo once again earlier this week speaks of a different point of view, however. The panel is comprised of 64 persons. Each of them is a Hall of Famer himself. And each knows and understands what it takes to be one, presumably. So why did Santo receive only 61 percent of the vote, 14 short of the number required for induction? In the minds of some committee members, there are too many gray areas to allow for it, and here's what they are: • Team success. In the prime of Santo's career, which extended from the 1963 to 1972 seasons, the Cubs lost more games (808) than they won (804). Only once did they total more than 87 victories in that span. -

November 07 Retirees Newsletter

November 2007 Issue 3 Academic Year 2007-2008 Retirees Newsletter PROFESSIONAL STAFF CONGRESS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT: I thank Jim Perlstein for this colorful summary of Mr. Marvin Miller’s remarks. BALLPLAYERS AND UNIONISM: the standard player contract had MARVIN MILLER’S TALK amounted to serfdom. RESONATES WITH CUNY RETIREES Though young and inexperienced with unions, Miller found major Marvin Miller, retired leaguers to be fast learners Executive Director of the who quickly came to appreciate Major League’s Baseball their collective power through Players’ Association, collective action. The relatively provided the November small number of ballplayers meeting of the Retirees who make it to the major Chapter with a compelling leagues made it possible to retrospective on the origin and have regular one-on-one progress of baseball unionism since meetings with each player, in the 1960’s. addition to annual group meetings with each team during spring While some PSCers had looked training. And the union maintained forward to a nostalgic afternoon - an open door policy at its New York “Robin Roberts…I remember Robin headquarters so that players could Roberts” - Miller would have none of drop in during the season as their it. He kept his talk and his teams cycled through the city for responses to the numerous scheduled games. All of this, Miller questions focused on the nature of said, speeded the education unionism, particularly the question of process, kept members engaged unionism among celebrities and provided Miller and his small conditioned to see themselves as staff with the opportunity to hammer privileged independent contractors. home the idea that the members are And he stressed that ballplayers’ the union. -

Chicago Tribune: Baseball World Lauds Jerome

Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman -- chicagotribune.com Page 1 of 3 www.chicagotribune.com/sports/chi-22-holtzman-baseballjul22,0,5941045.story chicagotribune.com Baseball world lauds Jerome Holtzman Ex-players, managers, officials laud Holtzman By Dave van Dyck Chicago Tribune reporter July 22, 2008 Chicago lost its most celebrated chronicler of the national pastime with the passing of Jerome Holtzman, and all of baseball lost an icon who so graciously linked its generations. Holtzman, the former Tribune and Sun-Times writer and later MLB's official historian, indeed belonged to the entire baseball world. He seemed to know everyone in the game while simultaneously knowing everything about the game. Praise poured in from around the country for the Hall of Famer, from management and union, managers and players. "Those of us who knew him and worked with him will always remember his good humor, his fairness and his love for baseball," Commissioner Bud Selig said. "He was a very good friend of mine throughout my career in the game and I will miss his friendship and counsel. I extend my deepest sympathies to his wife, Marilyn, to his children and to his many friends." The men who sat across from Selig during labor negotiations—a fairly new wrinkle in the game that Holtzman became an expert at covering—remembered him just as fondly. "I saw Jerry at Cooperstown a few years ago and we talked old times well into the night," said Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Players Association. "We always had a good relationship. He was a careful writer and, covering a subject matter he was not familiar with, he did a remarkably good job." "You don't develop the reputation he had by accident," said present-day union boss Donald Fehr.