The History of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption, 9 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

Lot# Title Bids Sale Price 1

Huggins and Scott'sAugust 7, 2014 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Ultimate 1974 Topps Baseball Experience: #1 PSA Graded Master, Traded & Team Checklist Sets with (564) PSA12 10,$ Factory82,950.00 Set, Uncut Sheet & More! [reserve met] 2 1869 Peck & Snyder Cincinnati Red Stockings (Small) Team Card SGC 10—First Baseball Card Ever Produced!22 $ 16,590.00 3 1933 Goudey Baseball #106 Napoleon Lajoie—PSA Authentic 21 $ 13,035.00 4 1908-09 Rose Co. Postcards Walter Johnson SGC 45—First Offered and Only Graded by SGC or PSA! 25 $ 10,072.50 5 1911 T205 Gold Border Kaiser Wilhelm (Cycle Back) “Suffered in 18th Line” Variation—SGC 60 [reserve not met]0 $ - 6 1915 E145 Cracker Jack #30 Ty Cobb PSA 5 22 $ 7,702.50 7 (65) 1909-11 T206 White Border Singles with (40) Graded Including (4) Hall of Famers 16 $ 2,370.00 8 (37) 1909-11 T206 White Border PSA 1-4 Graded Cards with Willis 8 $ 1,125.75 9 (5) 1909-11 T206 White Borders PSA Graded Cards with Mathewson 9 $ 711.00 10 (3) 1911 T205 Gold Borders with Mordecai Brown, Walter Johnson & Cy Young--All SGC Authentic 12 $ 711.00 11 (3) 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb SGC Authentic Singles--Different Poses 14 $ 1,777.50 12 1909-11 T206 White Borders Walter Johnson (Portrait) & Christy Mathewson (White Cap)--Both SGC Authentic 9 $ 444.38 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Green Portrait) SGC 55 12 $ 3,555.00 14 1909-11 T205 & T206 Hall of Famers with Lajoie, Mathewson & McGraw--All SGC Graded 12 $ 503.63 15 (4) 1887 N284 Buchner Gold Coin SGC 60 Graded Singles 4 $ 770.25 16 (6) -

Beyond Right Field Fence

Homers by Ruth and Bodie Win for Yankees Ov^r Cardinals.Giants Defeat San Antonio Babe's Clout Clears House McGraw Shifts How to Start the Day Wrong By BRIGGS Ponteau Beats Beyond Right Field Fence Veteran Benton ArchieWalker FlMC MORMiM<$- Tnewe^s <Seo«se PaptagaS- Tm« TRA1M 13 LATE BUT A nic«s 3e5AT BY The MrNM- - . Louisiana Towii Declares Half To Second Nine WALK To J'Ll tAJAve To HIM-- t DOm'T WHAT O*" IT ? <S66 NNMI* Wimdoxju- - njovjl> for a in Honor of A NiCE B»i5K K*JOVAJ HIM VERY XA^eCX- 8l)T WHY JUMP ON TMtr RA.IL- In 3 Holiday Tne ROAoa - - CaMFORTABLE R|7>E To Rounds STaTiOm l'M rceuiHG FIWE Tmev'Re ooinG Bambino's First and TctxaJM --'. TVll-S IS a Visit, Capacity Croyd Gives No r ^est AS LIGHT 7hsir se-sr PlN(2"TRAlf>» Sees the INines in a Fast Contest Manager Explana AS A FeATHE« 135-Ponnd State Big League tion of Move That Ma^ Loses Chaaipion Be Result of "Zim" Decision to Negre By R. J. Kelly AlTaii Boxer in Bout at Garden LAKE CHARLES, La., March 16.-.The Yankees emerged triumphant. By Charles A. Taylor The Amateur Athletic from their first test of the training season against Union held » major league opposi- SAN ANTONIO, Tex., March 16..Th< boxing tournament at Madison tion by defeating Branch Rickey's Cardinala in an old-fashioned slugging Giants defeated tho San Antonio Bcar.< Garden last Square' contest night. At least it wa, here this afternoon by a score of 14 to 9. -

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

Willamette Valley Babe Ruth Local Playing Rules

Willamette Valley Babe Ruth Local Playing Rules Babe Ruth League National Rule Changes The International Board of Directors has approved the following rule changes beginning with the 2018 season. These changes will be reflected in the 2018 Babe Ruth League, Inc. Rules and Regulations. 1. Cal Ripken Baseball, Babe Ruth Baseball, and Babe Ruth Softball - For the 2018 season, the team composition rule will be adjusted to allow one (1) manager and three (3) coaches per team for all Divisions of Babe Ruth League, Inc., for Local League Competition and Tournament Competition, provided such managers and coaches meet all Coaching Education and Background Check requirements. For tournament play - should a team advance to a World Series, the 3rd coach will be responsible for their own travel and lodging (remember a tournament manager or coach must be selected from the league or division in which they manage or coach). 2. Approved Bats - Cal Ripken Baseball and Babe Ruth Baseball a. Cal Ripken Division - All non-wood bats must have the USA Bat Marking. The Barrel 5 Maximum is 2 /8". No BBCOR Bats are permitted in the Cal Ripken Division. For the T- Ball Division, bats must be marked with the USA Bat T-Ball Stamp. b. Babe Ruth Baseball 13-15 Division – All non-wood bats must have the USA Bat Marking or 5 marked BBCOR .50. Bat Barrel - 2 /8". c. Babe Ruth Baseball 16-18 Division - All non-wood bats MUST be a BBCOR .50 and no 5 greater than a -3. Barrel - 2 /8". 3. Rule 11.05; Number 4, Tournament Pitching Rules, Paragraph a. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Class 2 - the 2004 Red Sox - Agenda

The 2004 Red Sox Class 2 - The 2004 Red Sox - Agenda 1. The Red Sox 1902- 2000 2. The Fans, the Feud, the Curse 3. 2001 - The New Ownership 4. 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) 5. The 2004 World Series The Boston Red Sox Winning Percentage By Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .522 .572 .375 .483 .563 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .510 .486 .528 .553 .521 2001-10 11-17 Total .594 .549 .521 Red Sox Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 1 WS/2 Pnt 4 WS/4 Pnt 0 0 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt/1 Div 1 Div 2001-10 11-17 Total 2 WS/2 Pnt 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 8 WS/13 Pnt/4 Div The Most Successful Team in Baseball 1903-1919 • Five World Series Champions (1903/12/15/16/18) • One Pennant in 04 (but the NL refused to play Cy Young Joe Wood them in the WS) • Very good attendance Babe Ruth • A state of the art Tris stadium Speaker Harry Hooper Harry Frazee Red Sox Owner - Nov 1916 – July 1923 • Frazee was an ambitious Theater owner, Promoter, and Producer • Bought the Sox/Fenway for $1M in 1916 • The deal was not vetted with AL Commissioner Ban Johnson • Led to a split among AL Owners Fenway Park – 1912 – Inaugural Season Ban Johnson Charles Comiskey Jacob Ruppert Harry Frazee American Chicago NY Yankees Boston League White Sox Owner Red Sox Commissioner Owner Owner The Ruth Trade Sold to the Yankees Dec 1919 • Ruth no longer wanted to pitch • Was a problem player – drinking / leave the team • Ruth was holding out to double his salary • Frazee had a cash flow crunch between his businesses • He needed to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park • Frazee had two trade options: • White Sox – Joe Jackson and $60K • Yankees - $100K with a $300K second mortgage Frazee’s Fire Sale of the Red Sox 1919-1923 • Sells 8 players (all starters, and 3 HOF) to Yankees for over $450K • The Yankees created a dynasty from the trading relationship • Trades/sells his entire starting team within 3 years. -

A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions

Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions Joseph J. McMahon Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph J. McMahon Jr., A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions, 2 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 213 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McMahon: A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF BASEBALL'S THREE ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS JOSEPH J. MCMAHON, JR.* AND JOHN P. RossI** I. INTRODUCTION What is professional baseball? It is difficult to answer this ques- tion without using a value-laden term which, in effect, tells us more about the speaker than about the subject. Professional baseball may be described as a "sport,"' our "national pastime,"2 or a "busi- ness."3 Use of these descriptors reveals the speaker's judgment as to the relative importance of professional baseball to American soci- ety. Indeed, all of the aforementioned terms are partially accurate descriptors of professional baseball. When a Scranton/Wilkes- Barre Red Barons fan is at Lackawanna County Stadium 4 ap- plauding a home run by Gene Schall, 5 the fan is engrossed in the game's details. -

Risk of Injury from Baseball and Softball in Children

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness Risk of Injury From Baseball and Softball in Children ABSTRACT. This statement updates the 1994 American their thoraces may be more elastic and more easily Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on baseball and compressed.2 Statistics compiled by the US Con- softball injuries in children. Current studies on acute, sumer Product Safety Commission1 indicate that overuse, and catastrophic injuries are reviewed with em- there were 88 baseball-related deaths to children in phasis on the causes and mechanisms of injury. This this age group between 1973 and 1995, an average of information serves as a basis for recommending safe about 4 per year. This average has not changed since training practices and the appropriate use of protective equipment. 1973. Of these, 43% were from direct-ball impact with the chest (commotio cordis); 24% were from direct-ball contact with the head; 15% were from ABBREVIATION. NOCSAE, National Operating Committee on impacts from bats; 10% were from direct contact with Standards for Athletic Equipment. a ball impacting the neck, ears, or throat; and in 8%, the mechanism of injury was unknown. INTRODUCTION Direct contact by the ball is the most frequent aseball is one of the most popular sports in the cause of death and serious injury in baseball. Preven- United States, with an estimated 4.8 million tive measures to protect young players from direct Bchildren 5 to 14 years of age participating an- ball contact include the use of batting helmets and nually in organized and recreational baseball and face protectors while at bat and on base, the use of softball. -

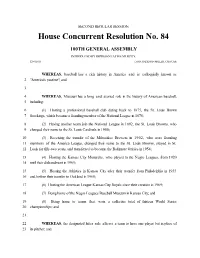

House Concurrent Resolution No. 84

SECOND REGULAR SESSION House Concurrent Resolution No. 84 100TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY INTRODUCED BY REPRESENTATIVE MURPHY. 5299H.01I DANA RADEMAN MILLER, Chief Clerk WHEREAS, baseball has a rich history in America and is colloquially known as 2 "America's pastime"; and 3 4 WHEREAS, Missouri has a long and storied role in the history of American baseball, 5 including: 6 (1) Hosting a professional baseball club dating back to 1875, the St. Louis Brown 7 Stockings, which became a founding member of the National League in 1876; 8 (2) Having another team join the National League in 1892, the St. Louis Browns, who 9 changed their name to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900; 10 (3) Receiving the transfer of the Milwaukee Brewers in 1902, who were founding 11 members of the America League, changed their name to the St. Louis Browns, played in St. 12 Louis for fifty-two years, and transferred to become the Baltimore Orioles in 1954; 13 (4) Hosting the Kansas City Monarchs, who played in the Negro Leagues, from 1920 14 until their disbandment in 1965; 15 (5) Hosting the Athletics in Kansas City after their transfer from Philadelphia in 1955 16 and before their transfer to Oakland in 1968; 17 (6) Hosting the American League Kansas City Royals since their creation in 1969; 18 (7) Being home of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City; and 19 (8) Being home to teams that won a collective total of thirteen World Series 20 championships; and 21 22 WHEREAS, the designated hitter rule allows a team to have one player bat in place of 23 its pitcher; and HCR 84 2 24 WHEREAS, the American League adopted the designated hitter rule in 1973; and 25 26 WHEREAS, the American League played for seven decades without the designated 27 hitter rule; and 28 29 WHEREAS, the National League, including the St. -

Lawrence Peter Berra Was Born on May 12, 1925. He Played Major League Baseball for 19 Years for the New York Yankees. He Played

Lawrence Peter Berra was born on May 12, 1925. He played Major League Baseball for 19 years for the New York Yankees. He played on 10 World Series Championship teams, is a MLB Hall of Famer and has some awe-inspiring stats. His name is consistently brought up as one of the best catchers in baseball history, and he was voted to the Team of the Century in 1999. Amazing accomplishments aside, they probably aren't how you know Lawrence. You know him as Yogi, a nickname given to him by a friend who likened his cross-legged sitting to a yogi. Yogi is famous for his fractured English, and sometimes nonsensical quotes, but there seems to be no end to his fan's love for him. Here are 25 Yogi Berra quotes that will make you shake your head and smile. 1. "It's like deja vu all over again." 2. "We made too many wrong mistakes." 3. "You can observe a lot just by watching." 4. "A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore." 5. "He hits from both sides of the plate. He's amphibious." 6. "If the world was perfect, it wouldn't be." 7. "If you don't know where you're going, you might end up some place else." 8. Responding to a question about remarks attributed to him that he did not think were his: "I really didn't say everything I said." 9. "The future ain't what it used to be." 10. "I think Little League is wonderful. It keeps the kids out of the house." 11. -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – Jan. 23, 2019 Walker short in next-to-last year on HOF ballot Former slugger receives 54.6 percent of vote; Helton gets 16.5 percent in first year of eligibility Thomas Harding | MLB.com | Jan. 22, 2019 DENVER -- Former Rockies star Larry Walker introduced himself under a different title during his conference call with Denver media on Tuesday: "Fifty-four-point-six here." That's the percentage of voters who checked Walker in his ninth year of 10 on the Baseball Writers' Association of America Hall of Fame ballot. It's a dramatic jump from his previous high, 34.1 percent last year -- an increase of 88 votes. However, he's going to need an 87-vote leap to reach the requisite 75 percent next year, his final season of eligibility. Jayson Stark of the Athletic noted during MLB Network's telecast that the only player to receive a jump of at least 80 votes in successive years was former Reds shortstop Barry Larkin, who was inducted in 2012. But when publicly revealed ballots had him approaching the mid-60s in percentage, Walker admitted feeling excitement he hadn't experienced in past years. "I haven't tuned in most years because there's been no chance of it really happening," Walker said. "It was nice to see this year, to watch and to have some excitement involved with it. "I was on Twitter and saw the percentages that were getting put out there for me. It made it more interesting. I'm thankful to be able to go as high as I was there before the final announcement." When discussing the vote, one must consider who else is on the ballot.