1 Understanding Aristotle Lonergan Institute for the “Good Under

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquinas' Principle of Individuation

Aquinas' Principle of Individuation Patrick W. Hughes Denison University Saint Thomas Aquinas, the Thirteenth Century Catholic theologian and philosopher was one of the first Medieval philosophers to attempt to reconcile the newly re-introduced Aristotelian system with the Catholic religious thought ofthe day. Aquinas' numerous commentaries on Aristotle and his adoption of the Aristotelian thought form the basis for the whole of Aquinian metaphysics (as well as the basic Aristotileanism which pervades Aquinas' whole systematic philosophy), In this paper I will deal with a specific yet fundamental principle ofAquinianmetaphysics-the principle of individuation. On first reading of the Aquinian texts, the principle of individuation appears to be stated succinctly, yet further investigation into the concept of individuation reveals problems and ambiguities. As it is necessary for an understanding of the problem of individuation in the Aquinian system, I will start off with the basic ontology ofAquinas and then will proceed with one interpretation of the ambiguities which exist in the texts regarding the principle of individuation. I will then give a counter interpretation that Aquinas might level against my interpretation and the problems ofmy interpretation; finally, I will analyze any problems that arise from the Aquinian response. 1. Primary Substance in Aristotle and Aquinas The difficulty in dealing with systematic philosophy is that it is difficult to know where to begin, since each concept is built upon previous concepts and all of the concepts are fundamentally interrelated. Neverthe less, I shall start by explicating Aquinas' fundamental ontology. Aquinas, following Aristotle, points out that the world is made up of individual things-or what Aquinas calls "primary substances", Socrates, Rover, and the pine tree in my yard are all existing individual primary substances in the world. -

The Concept Of'nature'in Aristotle, Avicenna and Averroes

doi: 10.1590/0100-512X2015n13103cb THE CONCEPT OF ‘NATURE’ IN ARISTOTLE, AVICENNA AND AVERROES* Catarina Belo** [email protected] RESUMO O presente artigo trata da ‘natureza’ enquanto objeto da física, ou da ciência natural, tal como descrita por Aristóteles na “Física”. Também trata das definições da natureza, especificamente a natureza física, fornecidas por Avicena (m. 1037) e Averróis (m. 1198) nos seus comentários à “Física” de Aristóteles. Avicena e Averróis partilham da conceção da natureza de Aristóteles enquanto princípio de movimento e repouso. Enquanto para Aristóteles o objeto da física parece ser a natureza, ou aquilo que existe por natureza, Avicena defende que é o corpo natural, e Averróis afirma que o objeto da física, ou ciência natural, consiste nas coisas naturais, apresentando uma ênfase algo diferente. Palavras-chave Natureza, física, substância, Aristóteles, Avicena, Averróis. ABSTRACT This study is concerned with ‘nature’ specifically as the subject-matter of physics, or natural science, as described by Aristotle in his “Physics”. It also discusses the definitions of nature, and more specifically physical nature, provided by Avicenna (d. 1037) and Averroes (d. 1198) in their commentaries on Aristotle’s “Physics”. Avicenna and Averroes share Aristotle’s conception of nature as a principle of motion and rest. While according to Aristotle the subject matter of physics appears to be nature, * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the International Medieval Congress 2008, University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 7-10 July 2008. I am grateful for the comments on my paper by the other congress participants. ** Associate Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy – The American University in Cairo. -

Form, Essence, Soul: Distinguishing Principles of Thomistic Metaphysics

FORM, ESSENCE, SOUL: DISTINGUISHING PRINCIPLES OF THOMISTIC METAPHYSICS JOSHUA P. HOCHSCHILD I. INTRODUCTION What is the difference between the substantial form, the essence, and the soul of a living material substance? Each of these three items would normally be considered in a course in Thomistic philosophy. In my experience, there reaches a point where students begin to wonder how these terms are related and even whether it is necessary to de scribe the metaphysical principles of things in so many different ways. I have found it useful, for my own understanding and my teaching, to exploit, even to foster, some potential confusions precisely in order to focus on them, and in the process illuminate certain distinctions and insights in Thomistic philosophy. II. CONFUSIONS Presentations of Thomistic metaphysics can tend to present the substantial form, essence, and soul as if they are basically the same thing. Aquinas himself, after all, sometimes treats "form" as syn onymous with "essence,"1 and they seem to serve the same basic metaphysical task: both are causes not only of a thing's being the kind of thing it is, but of its just being.2 And, as causes, the causality exercised by both the essence and the form is formal, not material or efficient.3 As for the soul, Aquinas of course adopts its Aristotelian 1 Aquinas, De Ente et Essentia, ch. 1: "Dicitur etiam forma secundum quod per formam significatur certitudo uniuscuiusque rei, ut <licit Avicenna in II Metaphysicae suae." 2 Aquinas, De Ente et Essentia, ch. 1: "Et hoc est quod Philosophus frequenter nominat quod quid erat esse, id est hoc per quod aliquid habet esse quid." De Principiis Naturae, ch. -

An Argument for Substantial Form

An Argument for Substantial Form Steven Baldner St. Francis Xavier University I provide an argument, based on Thomistic principles, for substantial form, understood as the single principle of substantial actuality for any natural substance. To make this argument, I distinguish between substance and accident, between the natural and the artificial, and between ontological and methodological reduction. I respond to two objections to the Thomistic doctrine of substantial form raised by Benjamin Hill: I explain how it is possible for Thomas to account for the presence of elements in compounds and also to account for the fact of natural instances that fail to realize the full reality of the substantial form (“monsters”). I begin by offering my sincere gratitude and appreciation for the excellent paper we have heard from Professor Hill.1 I am going to attempt to argue against some of the conclusions reached by Prof. Hill, but I do so with humility, for, however much I might be convinced of the truth of Thomistic monism, I am even more certain of my own inadequacy to the task of competing with the metaphysical analysis we have already seen. My goal here is not so much to give you better arguments, for I don’t think that I can, as to give you some reason to try to find better arguments yourselves. And perhaps you will do just that in the question period. I shall attempt to do two things in this paper: first, to give an argument for substantial form and second to give replies to some of the objections raised so well by Prof. -

Reverend Matthew L. Lamb

Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. Summer 2014 Reverend Matthew L. Lamb Priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Professor of Theology Ave Maria University 5050 Ave Maria Boulevard Ave Maria, Florida 34142-9670 Tel. 239-867-4433 [email protected] [email protected] I. EDUCATION: 1974 Doktor der Theologie summa cum laude, Catholic Faculty of Theology, Westfälsche Wilhelms University, Münster, Germany. 1967-71 Doctoral studies, University of Tübingen (one semester) and Münster (six semesters). 1966 S.T.L. cum laude, the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, Italy. 1964-67 Graduate studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. August 14, 1962 ordained to the Roman Catholic Priesthood, Trappist Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia; now a Roman Catholic priest incardinated in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. 1960-64 Theological studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Monastery of the Holy Spirit, Conyers, Georgia. 1957-60 Philosophical studies at the Trappist Monastic Scholasticate, Conyers, Georgia. II. TEACHING: A. Marquette University, College of Arts & Sciences 1973-74 Instructor in Systematic Theology B. Marquette University, Graduate School 1974-79 Assistant Professor of Fundamental Theology 1979-85 Associate Professor of Fundamental Theology C. University of Chicago, Divinity School & Graduate School 1980 Visiting Associate Professor in Philosophical Theology. Page 1 of 44 Fr. Matthew L. Lamb’s C.V. Summer 2014 D. Boston College, College of Arts and Sciences, Graduate School 1985-88 Associate Professor of Theology 1989 - 2004 Professor of Theology E. Ave Maria University, Department of Theology 2004 - Professor of Theology and Chairman III. GRANTS AND ACADEMIC HONORS: 2009 – Cardinal Maida Chair, Ave Maria University. -

Bo St O N College F a C T B

BOSTON BOSTON COLLEGE 2012–2013 FACT BOOK BOSTON COLLEGE FACT BOOK 2012-2013 Current and past issues of the Boston College Fact Book are available on the Boston College web site at www.bc.edu/factbook © Trustees of Boston College 1983-2013 2 Foreword Foreword The Office of Institutional Research is pleased to present the Boston College Fact Book, 2012-2013, the 40th edition of this publication. This book is intended as a single, readily accessible, consistent source of information about the Boston College community, its resources, and its operations. It is a summary of institutional data gathered from many areas of the University, compiled to capture the 2011-2012 Fiscal and Academic Year, and the fall semester of the 2012-2013 Academic Year. Where appropriate, multiple years of data are provided for historical perspective. While not all-encompassing, the Fact Book does provide pertinent facts and figures valuable to administrators, faculty, staff, and students. Sincere appreciation is extended to all contributors who offered their time and expertise to maintain the greatest possible accuracy and standardization of the data. Special thanks go to graduate student Monique Ouimette for her extensive contribution. A concerted effort is made to make this publication an increasingly more useful reference, at the same time enhancing your understanding of the scope and progress of the University. We welcome your comments and suggestions toward these goals. This Fact Book, as well as those from previous years, is available in its entirety at www.bc.edu/factbook. -

Substance and Artifact in Thomas Aquinas Michael W

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 2004 Substance and artifact in Thomas Aquinas Michael W. Rota University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.stthomas.edu/cas_phil_pub Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Rota, Michael W., "Substance and artifact in Thomas Aquinas" (2004). Philosophy Faculty Publications. 19. http://ir.stthomas.edu/cas_phil_pub/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY QUARTERLY Volume 21, Number 3, July 2004 SUBSTANCE AND ARTIFACT IN THOMAS AQUINAS Michael Rota Introduction urrent interpretations of Aquinas often attribute to him the claim Cthat no artifact is a substance, or, more precisely, the claim that, (A1) No artifact is a substance in virtue of its form. Robert Pasnau, for example, tells us that “Aquinas is committed to the view that all artifacts are nonsubstances with respect to their form.”1 And Eleonore Stump writes: An artifact is thus a composite of things confi gured together into a whole but not by a substantial form. Since only something confi gured by a substantial form is a substance, no artifact is a substance.2 In fact, however, Aquinas’s position on the metaphysical status of ar- tifacts is more nuanced than these standard interpretations suppose. This paper will examine three hitherto overlooked passages in Aquinas’s writings in an attempt to clarify his position, and to show how it (his actual position) can overcome some of the philosophical problems which pose diffi culties for the stronger claims often attributed to him. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Hylomorphism and Mereology Also Available in the Series

Hylomorphism and Mereology Also available in the series: The Immateriality of the Human Mind, the Semantics of Analogy, and the Conceivability of God Volume 1: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Categories, and What Is Beyond Volume 2: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Knowledge, Mental Language, and Free Will Volume 3: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Mental Representation Volume 4: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Universal Representation, and the Ontology of Individuation Volume 5: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Medieval Skepticism, and the Claim to Metaphysical Knowledge Volume 6: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Medieval Metaphysics; or Is It “Just Semantics”? Volume 7: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics After God, with Reason Alone-Saikat Guha Commemorative Volume Volume 8: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics The Demonic Temptations of Medieval Nominalism Volume 9: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Skepticism, Causality and Skepticism about Causality Volume 10: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Metaphysical Themes, Medieval and Modern Volume 11: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics Maimonides on God and Duns Scotus on Logic and Metaphysics Volume 12: Proceedings of the Society for Medieval Logic and Metaphysics The Metaphysics of -

Aristotle's Theory of Powers

Aristotle’s Theory of Powers by Umer Shaikh A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Philosophy) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Victor Caston, chair Professor Sara Abhel-Rappe Professor David Manley Professor Tad Schmaltz Umer Shaikh [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8062-7932 © Umer Shaikh 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ....................................... v Chapter 1 Introduction ................................... 1 1.1 The Question ............................... 1 1.2 Powers and Dispositions ......................... 2 1.3 Remark on Translation and Texts .................... 3 1.4 Preliminary Answers ........................... 3 1.4.1 Powers are Efficient Causes ................... 4 1.4.2 Powers and Change ....................... 5 1.4.3 Being in Potentiality and Possibility .............. 6 1.4.4 The Foundation of Modality .................. 8 1.4.5 Possibilities from Powers .................... 9 1.4.6 Conclusion ............................ 11 1.5 Remarks About Scope of Discussion and About the Development of the δύναμις Concept ........................... 12 1.5.1 Scope ............................... 12 1.5.2 Δύναμις in Various Texts .................... 12 1.5.3 Previous Attempts to Find Consistency ............ 18 1.5.3.1 Kenny .......................... 18 1.5.3.2 Hintikka ......................... 21 1.5.4 Drawing Some Morals ..................... 22 2 Powers and Efficient Causation ......................... 24 2.1 -

Curriculum Vitae David Fleischacker, Ph.D

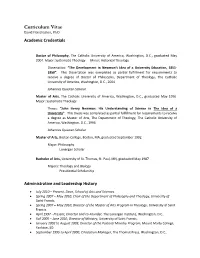

Curriculum Vitae David Fleischacker, Ph.D. Academic Credentials Doctor of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., graduated May 2004. Major: Systematic Theology Minor: Historical Theology Dissertation: “The Development in Newman’s Idea of a University Education, 1851- 1858”. This Dissertation was completed as partial fulfillment for requirements to receive a degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Theology, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., 2004 Johannes Quasten Scholar Master of Arts, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., graduated May 1996. Major: Systematic Theology Thesis: “John Henry Newman: His Understanding of Science in The Idea of a University”. This thesis was completed as partial fulfillment for requirements to receive a degree as Master of Arts, The Department of Theology, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., 1996. Johannes Quasten Scholar Master of Arts, Boston College, Boston, MA, graduated September 1992. Major: Philosophy Lonergan Scholar Bachelor of Arts, University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN, graduated May 1987 Majors: Theology and Biology Presidential Scholarship Administrative and Leadership History • July 2010 – Present, Dean, School of Arts and Sciences. • Spring 2007 – May 2010, Chair of the Department of Philosophy and Theology, University of Saint Francis. • Spring 2007 – May 2010, Director of the Master of Arts Program in Theology, University of Saint Francis. • April 1997 - Present, Director and co-Founder, The Lonergan Institute, Washington, D.C.. • Fall 2005 – June 2010, Director of Ministry, University of Saint Francis. • January 2002 to August 2003, Director of the Pastoral Ministry Program, Mount Marty College, Yankton, SD. • September 1995 to April 2000, Circulation Manager, The Thomist Press, Washington, D.C. -

2000–2001 Fact Book

boston college FACT BOOK 2001 The Boston College Fact Book is on the World Wide Web! Current and past issues are available on the Boston College web site at http://www.bc.edu/factbook Nondiscrimination Statement Founded by the Society of Jesus in 1863, Boston College is dedicated to intellectual excellence and to its Jesuit, Catholic mission and heritage. Committed to maintaining a welcoming environment for all people, the University recognizes the important contribution a diverse community of students, faculty and administrators makes to the advancement of its goals and ideals. Boston College rejects and condemns all forms of harassment, and it has developed procedures to redress incidents of harassment against any members of its community, whatever the basis or circumstance. Moreover, in accordance with all applicable state and federal laws, Boston College does not discriminate in employment, housing, or education on the basis of a person’s race, religion, color, national origin, age, sex, marital or parental status, veteran status, or disabilities. In addition, in a manner faithful to the Jesuit, Catholic principles and values that sustain its mission and heritage, Boston College is in compliance with applicable state laws providing equal opportunity without regard to sexual orientation. Boston College has designated the Director of Affirmative Action to coordinate its efforts to comply with and carry out its responsibilities to prevent discrimination in accordance with state and federal laws. Any applicant for admission or employment, as well as all students, faculty members, and employees, are welcome to raise any questions regarding violation of this policy with Barbara Marshall, Director of Affirmative Action, More Hall 315, 552-2947.