Arxiv:Hep-Ph/9912247V1 6 Dec 1999 MGNTV COSMOLOGY IMAGINATIVE Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 8: the Big Bang and Early Universe

Astr 323: Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology Spring Quarter 2014, University of Washington, Zeljkoˇ Ivezi´c Lecture 8: The Big Bang and Early Universe 1 Observational Cosmology Key observations that support the Big Bang Theory • Expansion: the Hubble law • Cosmic Microwave Background • The light element abundance • Recent advances: baryon oscillations, integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect, etc. 2 Expansion of the Universe • Discovered as a linear law (v = HD) by Hubble in 1929. • With distant SNe, today we can measure the deviations from linearity in the Hubble law due to cosmological effects • The curves in the top panel show a closed Universe (Ω = 2) in red, the crit- ical density Universe (Ω = 1) in black, the empty Universe (Ω = 0) in green, the steady state model in blue, and the WMAP based concordance model with Ωm = 0:27 and ΩΛ = 0:73 in purple. • The data imply an accelerating Universe at low to moderate redshifts but a de- celerating Universe at higher redshifts, consistent with a model having both a cosmological constant and a significant amount of dark matter. 3 Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) • The CMB was discovered by Penzias & Wil- son in 1965 (although there was an older mea- surement of the \sky" temperature by McKel- lar using interstellar molecules in 1940, whose significance was not recognized) • This is the best black-body spectrum ever mea- sured, with T = 2:73 K. It is also remark- ably uniform accross the sky (to one part in ∼ 10−5), after dipole induced by the solar mo- tion is corrected for. • The existance of CMB was predicted by Gamow in 1946. -

Homework 2: Classical Cosmology

Homework 2: Classical Cosmology Due Mon Jan 21 2013 You may find Hogg astro-ph/9905116 a useful reference for what follows. Ignore radiation energy density in all problems. Problem 1. Distances. a) Compute and plot for at least three sets of cosmological parameters of your choice the fol- lowing quantities as a function of redshift (up to z=10): age of the universe in Gyrs; angular size distance in Gpc; luminosity distance in Gpc; angular size in arcseconds of a galaxy of 5kpc in intrin- sic size. Choose one of them to be the so-called concordance cosmology (Ωm, ΩΛ, h) = (0.3, 0.7, 0.7), one of them to have non-zero curvature and one of them such that the angular diameter distance becomes negative. What does it mean to have negative angular diameter distance? [10 pts] b) Consider a set of flat cosmologies and find the redshift at which the apparent size of an object of given intrinsic size is minimum as a function of ΩΛ. [10 pts] 2. The horizon and flatness problems 1) Compute the age of the universe tCMB at the time of the last scattering surface of the cosmic microwave background (approximately z = 1000), in concordance cosmology. Approximate the horizon size as ctCMB and get an estimate of the angular size of the horizon on the sky. Patches of the CMB larger than this angular scale should not have been in causal contact, but nonetheless the CMB is observed to be smooth across the entire sky. This is the famous ”horizon problem”. -

Or Causality Problem) the Flatness Problem (Or Fine Tuning Problem

4/28/19 The Horizon Problem (or causality problem) Antipodal points in the CMB are separated by ~ 1.96 rhorizon. Why then is the temperature of the CMB constant to ~ 10-5 K? The Flatness Problem (or fine tuning problem) W0 ~ 1 today coupled with expansion of the Universe implies that |1 – W| < 10-14 when BB nucleosynthesis occurred. Our existence depends on a very close match to the critical density in the early Universe 1 4/28/19 Theory of Cosmic Inflation Universe undergoes brief period of exponential expansion How Inflation Solves the Flatness Problem 2 4/28/19 Cosmic Inflation Summary Standard Big Bang theory has problems with tuning and causality Inflation (exponential expansion) solves these problems: - Causality solved by observable Universe having grown rapidly from a small region that was in causal contact before inflation - Fine tuning problems solved by the diluting effect of inflation Inflation naturally explains origin of large scale structure: - Early Universe has quantum fluctuations both in space-time itself and in the density of fields in space. Inflation expands these fluctuation in size, moving them out of causal contact with each other. Thus, large scale anisotropies are “frozen in” from which structure can form. Some kind of inflation appears to be required but the exact inflationary model not decided yet… 3 4/28/19 BAO: Baryonic Acoustic Oscillations Predict an overdensity in baryons (traced by galaxies) ~ 150 Mpc at the scale set by the distance that the baryon-photon acoustic wave could have traveled before CMB recombination 4 4/28/19 Curves are different models of Wm A measure of clustering of SDSS Galaxies of clustering A measure Eisenstein et al. -

A Different Derivation of the Calogero Conjecture

1 A Different Derivation of the Calogero Conjecture Ioannis Iraklis Haranas Physics and Astronomy Department York University 314 A Petrie Science Building Toronto – Ontario CANADA E mail: [email protected] Abstract: In a study by F. Calogero [1] entitled “ Cosmic origin of quantization” an expression was derived for the variability of h with time, and its consequences if any, of such an idea in cosmology were examined. In this paper we will offer a different derivation of the Calogero conjecture based on a postulate concerning a variable speed of light, [2] in conjuction with Weinberg’s relationship for the mass of an elementary particle. Introduction: Recently, Calogero studied and reconsidered the “ universal background noise which according to Nelsons’s stohastic mechanics [3,4,5] is the basis for the quantum behaviour. The position that Calogero took was that there might be a physical origin for this noise. He immediately pointed his attention to the gravitational interactions with the distant masses in the universe. Therefore, he argued for the case that Planck’s constant can be given by the following expression: 1/ 2 h ≈α G1/ 2m3/ 2[]R(t) (1) where α is a numerical constant = 1, G is the Newtonian gravitational constant, m is the mass of the hydrogen atom which is considered as the basic mass unit in the universe, and finally R(t) represents the radius of the universe or alternatively: “part of the universe which is accessible to gravitational interactions at time t.” [6]. We can obtain a rough estimate of the value of h if we just take into account that R(t) is the radius of the -28 universe evaluated at the present time t0 ie. -

Table of Contents (Print)

PERIODICALS PHYSICAL REVIEW D Postmaster send address changes to: For editorial and subscription correspondence, American Institute of Physics please see inside front cover Suite 1NO1 „ISSN: 0556-2821… 2 Huntington Quadrangle Melville, NY 11747-4502 THIRD SERIES, VOLUME 66, NUMBER 4 CONTENTS 15 AUGUST 2002 RAPID COMMUNICATIONS Density of cold dark matter (5 pages) ................................................... 041301͑R͒ Alessandro Melchiorri and Joseph Silk Shape of a small universe: Signatures in the cosmic microwave background (4 pages) . 041302͑R͒ R. Bowen and P. G. Ferreira Nonlinear r-modes in neutron stars: Instability of an unstable mode (5 pages) . 041303͑R͒ Philip Gressman, Lap-Ming Lin, Wai-Mo Suen, N. Stergioulas, and John L. Friedman Convergence and stability in numerical relativity (4 pages) . 041501͑R͒ Gioel Calabrese, Jorge Pullin, Olivier Sarbach, and Manuel Tiglio Stabilizing textures with magnetic ®elds (5 pages) . 041701͑R͒ R. S. Ward Friction in in¯aton equations of motion (5 pages) . 041702͑R͒ Ian D. Lawrie Singularity threshold of the nonlinear sigma model using 3D adaptive mesh re®nement (5 pages) . 041703͑R͒ Steven L. Liebling ARTICLES Neutrino damping rate at ®nite temperature and density (11 pages) . 043001 Eduardo S. Tututi, Manuel Torres, and Juan Carlos D'Olivo Numerical and analytical predictions for the large-scale Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect (13 pages) . 043002 Alexandre Refregier and Romain Teyssier In¯ation, cold dark matter, and the central density problem (12 pages) . 043003 Andrew R. Zentner and James S. Bullock Size of the smallest scales in cosmic string networks (4 pages) . 043501 Xavier Siemens, Ken D. Olum, and Alexander Vilenkin Semiclassical force for electroweak baryogenesis: Three-dimensional derivation (9 pages) . -

Variable Planck's Constant

Variable Planck’s Constant: Treated As A Dynamical Field And Path Integral Rand Dannenberg Ventura College, Physics and Astronomy Department, Ventura CA [email protected] [email protected] January 28, 2021 Abstract. The constant ħ is elevated to a dynamical field, coupling to other fields, and itself, through the Lagrangian density derivative terms. The spatial and temporal dependence of ħ falls directly out of the field equations themselves. Three solutions are found: a free field with a tadpole term; a standing-wave non-propagating mode; a non-oscillating non-propagating mode. The first two could be quantized. The third corresponds to a zero-momentum classical field that naturally decays spatially to a constant with no ad-hoc terms added to the Lagrangian. An attempt is made to calibrate the constants in the third solution based on experimental data. The three fields are referred to as actons. It is tentatively concluded that the acton origin coincides with a massive body, or point of infinite density, though is not mass dependent. An expression for the positional dependence of Planck’s constant is derived from a field theory in this work that matches in functional form that of one derived from considerations of Local Position Invariance violation in GR in another paper by this author. Astrophysical and Cosmological interpretations are provided. A derivation is shown for how the integrand in the path integral exponent becomes Lc/ħ(r), where Lc is the classical action. The path that makes stationary the integral in the exponent is termed the “dominant” path, and deviates from the classical path systematically due to the position dependence of ħ. -

Variable Planck's Constant

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 January 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202101.0612.v1 Variable Planck’s Constant: Treated As A Dynamical Field And Path Integral Rand Dannenberg Ventura College, Physics and Astronomy Department, Ventura CA [email protected] Abstract. The constant ħ is elevated to a dynamical field, coupling to other fields, and itself, through the Lagrangian density derivative terms. The spatial and temporal dependence of ħ falls directly out of the field equations themselves. Three solutions are found: a free field with a tadpole term; a standing-wave non-propagating mode; a non-oscillating non-propagating mode. The first two could be quantized. The third corresponds to a zero-momentum classical field that naturally decays spatially to a constant with no ad-hoc terms added to the Lagrangian. An attempt is made to calibrate the constants in the third solution based on experimental data. The three fields are referred to as actons. It is tentatively concluded that the acton origin coincides with a massive body, or point of infinite density, though is not mass dependent. An expression for the positional dependence of Planck’s constant is derived from a field theory in this work that matches in functional form that of one derived from considerations of Local Position Invariance violation in GR in another paper by this author. Astrophysical and Cosmological interpretations are provided. A derivation is shown for how the integrand in the path integral exponent becomes Lc/ħ(r), where Lc is the classical action. The path that makes stationary the integral in the exponent is termed the “dominant” path, and deviates from the classical path systematically due to the position dependence of ħ. -

Anisotropy of the Cosmic Background Radiation Implies the Violation Of

YITP-97-3, gr-qc/9707043 Anisotropy of the Cosmic Background Radiation implies the Violation of the Strong Energy Condition in Bianchi type I Universe Takeshi Chiba, Shinji Mukohyama, and Takashi Nakamura Yukawa Institute for Theoretical Physics, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-01, Japan (January 1, 2018) Abstract We consider the horizon problem in a homogeneous but anisotropic universe (Bianchi type I). We show that the problem cannot be solved if (1) the matter obeys the strong energy condition with the positive energy density and (2) the Einstein equations hold. The strong energy condition is violated during cosmological inflation. PACS numbers: 98.80.Hw arXiv:gr-qc/9707043v1 18 Jul 1997 Typeset using REVTEX 1 I. INTRODUCTION The discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) [1] verified the hot big bang cosmology. The high degree of its isotropy [2], however, gave rise to the horizon problem: Why could causally disconnected regions be isotropized? The inflationary universe scenario [3] may solve the problem because inflation made it possible for the universe to expand enormously up to the presently observable scale in a very short time. However inflation is the sufficient condition even if the cosmic no hair conjecture [4] is proved. Here, a problem again arises: Is inflation the unique solution to the horizon problem? What is the general requirement for the solution of the horizon problem? Recently, Liddle showed that in FRW universe the horizon problem cannot be solved without violating the strong energy condition if gravity can be treated classically [5]. Actu- ally the strong energy condition is violated during inflation. -

New Varying Speed of Light Theories

New varying speed of light theories Jo˜ao Magueijo The Blackett Laboratory,Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine South Kensington, London SW7 2BZ, UK ABSTRACT We review recent work on the possibility of a varying speed of light (VSL). We start by discussing the physical meaning of a varying c, dispelling the myth that the constancy of c is a matter of logical consistency. We then summarize the main VSL mechanisms proposed so far: hard breaking of Lorentz invariance; bimetric theories (where the speeds of gravity and light are not the same); locally Lorentz invariant VSL theories; theories exhibiting a color dependent speed of light; varying c induced by extra dimensions (e.g. in the brane-world scenario); and field theories where VSL results from vacuum polarization or CPT violation. We show how VSL scenarios may solve the cosmological problems usually tackled by inflation, and also how they may produce a scale-invariant spectrum of Gaussian fluctuations, capable of explaining the WMAP data. We then review the connection between VSL and theories of quantum gravity, showing how “doubly special” relativity has emerged as a VSL effective model of quantum space-time, with observational implications for ultra high energy cosmic rays and gamma ray bursts. Some recent work on the physics of “black” holes and other compact objects in VSL theories is also described, highlighting phenomena associated with spatial (as opposed to temporal) variations in c. Finally we describe the observational status of the theory. The evidence is slim – redshift dependence in alpha, ultra high energy cosmic rays, and (to a much lesser extent) the acceleration of the universe and the WMAP data. -

Fine Structure Constant| and Variable Speed of Light

Apeiron, Vol. 17, No. 2, April 2010 126 Fine Structure Constant| and Variable Speed of Light Guoyou HUANG 1. Geoscience institute, Guilin University of echnology No. 12, Jiangan St. Guilin, Guangxi. 541004 P.R. CHINA 2. Geophysics research institute, No.274 Geological Corp. No.69, Gaode St. Beihai, Guangxi. 536000 P.R.CHINA Email: [email protected] The fine structure constant has been proved to be no change even if the speed of light varies in gravitation field or in the history of cosmos. Lorentz transformation has also been proved to be a transformation of physical units between two different frames. This transformation implies a variable speed of light in gravitational field. Base on this variable speed of light, a new VSL cosmology model was established so as to solve the flatness problem and horizon problem in Standard Cosmology. Keywords: Fine structure constant, Lorentz Transformation, Variable Speed of Light, Flatness Problem, Horizon © 2010 C. Roy Keys Inc. — http://redshift.vif.com Apeiron, Vol. 17, No. 2, April 2010 127 1. Introduction The thinking of natural constants change with time was first made by Paul Dirac in 1937 [1] known as the Dirac Large Numbers Hypothesis, in which the gravitational constant was proposed to be inversely proportional to the age of universe in order to explain the relative weakness of the gravitational force compared to electrical forces. A group studying distant quasars claimed to have detected a variation in the fine structure constant [2], other groups claimed no detectable variation at much higher sensitivities [3][4][5][6]. Variable Speed of Light (VSL) cosmology has also been proposed by several authors [7][8][9][10] as an alternative choice for the well developed Inflationary Theory to explain the horizon problem and other puzzles in Standard Cosmology. -

The Rh = Ct Universe Without Inflation

A&A 553, A76 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201220447 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics The Rh = ct universe without inflation F. Melia Department of Physics, The Applied Math Program, and Department of Astronomy, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 26 September 2012 / Accepted 3 April 2013 ABSTRACT Context. The horizon problem in the standard model of cosmology (ΛDCM) arises from the observed uniformity of the cosmic microwave background radiation, which has the same temperature everywhere (except for tiny, stochastic fluctuations), even in regions on opposite sides of the sky, which appear to lie outside of each other’s causal horizon. Since no physical process propagating at or below lightspeed could have brought them into thermal equilibrium, it appears that the universe in its infancy required highly improbable initial conditions. Aims. In this paper, we demonstrate that the horizon problem only emerges for a subset of Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) cosmologies, such as ΛCDM, that include an early phase of rapid deceleration. Methods. The origin of the problem is examined by considering photon propagation through a FRW spacetime at a more fundamental level than has been attempted before. Results. We show that the horizon problem is nonexistent for the recently introduced Rh = ct universe, obviating the principal motivation for the inclusion of inflation. We demonstrate through direct calculation that, in this cosmology, even opposite sides of the cosmos have remained causally connected to us – and to each other – from the very first moments in the universe’s expansion. −35 −32 Therefore, within the context of the Rh = ct universe, the hypothesized inflationary epoch from t = 10 sto10 s was not needed to fix this particular “problem”, though it may still provide benefits to cosmology for other reasons. -

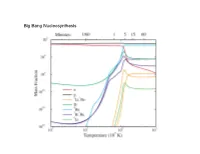

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis Finally, Relative Abundances Are Sensitive to Density of Normal (Baryonic Matter)

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis Finally, relative abundances are sensitive to density of normal (baryonic matter) Thus Ωb,0 ~ 4%. So our universe Ωtotal ~1 with 70% in Dark Energy, 30% in matter but only 4% baryonic! Case for the Hot Big Bang • The Cosmic Microwave Background has an isotropic blackbody spectrum – it is extremely difficult to generate a blackbody background in other models • The observed abundances of the light isotopes are reasonably consistent with predictions – again, a hot initial state is the natural way to generate these • Many astrophysical populations (e.g. quasars) show strong evolution with redshift – this certainly argues against any Steady State models The Accelerating Universe Distant SNe appear too faint, must be further away than in a non-accelerating universe. Perlmutter et al. 2003 Riese 2000 Outstanding problems • Why is the CMB so isotropic? – horizon distance at last scattering << horizon distance now – why would causally disconnected regions have the same temperature to 1 part in 105? • Why is universe so flat? – if Ω is not 1, Ω evolves rapidly away from 1 in radiation or matter dominated universe – but CMB analysis shows Ω = 1 to high accuracy – so either Ω=1 (why?) or Ω is fine tuned to very nearly 1 • How do structures form? – if early universe is so very nearly uniform Astronomy 422 Lecture 22: Early Universe Key concepts: Problems with Hot Big Bang Inflation Announcements: April 26: Exam 3 April 28: Presentations begin Astro 422 Presentations: Thursday April 28: 9:30 – 9:50 _Isaiah Santistevan__________ 9:50 – 10:10 _Cameron Trapp____________ 10:10 – 10:30 _Jessica Lopez____________ Tuesday May 3: 9:30 – 9:50 __Chris Quintana____________ 9:50 – 10:10 __Austin Vaitkus___________ 10:10 – 10:30 __Kathryn Jackson__________ Thursday May 5: 9:30 – 9:50 _Montie Avery_______________ 9:50 – 10:10 _Andrea Tallbrother_________ 10:10 – 10:30 _Veronica Dike_____________ 10:30 – 10:50 _Kirtus Leyba________________________ Send me your preference.