Precariousness of Employment and Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

145 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

145 bus time schedule & line map 145 Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich View In Website Mode The 145 bus line (Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bromsgrove: 5:26 PM (2) Bromsgrove: 8:00 AM (3) Droitwich Spa: 7:22 AM - 4:56 PM (4) Longbridge: 6:45 AM - 6:10 PM (5) Rubery: 9:13 AM - 12:50 PM (6) Wychbold: 6:16 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 145 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 145 bus arriving. -

Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01

Information for Partner Institutions Incoming Postgraduate Exchange Students 2019- 2020 Address Aston Business School Aston University Aston Triangle Birmingham B4 7ET United Kingdom Website www.abs.aston.ac.uk Erasmus Institution Code UK BIRMING 01 KEY CONTACTS: Saskia Hansen Institutional Erasmus Coordinator Pro-Vice Chancellor International Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 4664 Email: [email protected] Aston Business School Professor George Feiger Executive Dean Email Rebecca Okey Email: [email protected] Associate Dean Dr Geoff Parkes International Email: [email protected] International Relations Selena Teeling Manager Email: [email protected] Incoming and Outgoing International and Student Exchange Students Development Office Tel: ++44 (0) 121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate Student Elsa Zenatti-Daniels Development Lead Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3279 Email: [email protected] International and Student Ellie Crean Development Coordinator Tel: ++44 (0)121 204 3255 Email: [email protected] Contents Academic Information Important Dates 2 Entry Requirements 4 Application Procedures: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 5 Application Procedures: Double Degree Students 7 Credits and Course Layout 8 Study Methods and Grading System 9 MSc Module Selection: 1 or 2 Term Exchange 10 Course Selection: Double Degrees 11 The Aston Edge (MSc Double Degree) 12 Induction and Erasmus Form Details 13 Conditions for Eligibility 14 Practical Information Visas and Health Insurance 16 Accommodation 17 Support Facilities 20 Student Life at Aston 21 Employments and Careers Services 22 Health and Well Being at Aston 23 Academic Information Important Dates APPLICATION DEADLINES The nomination deadline for the fall term will be 1 June 2019 and the application deadline will be 20 June 2019 for double degree and Term 1 exchange students. -

Birmingham a Powerful City of Spirit

Curriculum Vitae Birmingham A powerful city of spirit Bio Timeline of Experience Property investment – As the second largest city in the UK, I have a lot to offer. I have great Birmingham, UK connections thanks to being so centrally located, as over 90% of the UK market is only a four hour drive away. The proposed HS2 railway is poised I’ve made a range to improve this further – residents will be able to commute to London in of investments over less than an hour. I thrive in fast-paced environments, as well as calmer the years. The overall waters – my vast canal route covers more miles than the waterways average house price is of Venice. £199,781, up 6% up 2018 - 2019 - 2019 2018 on the previous year. Truly a national treasure, my famed Jewellery Quarter contains over 800 businesses specialising in handcrafted or vintage jewellery and produces 40% of the UK’s jewellery. Edgbaston is home to the famed cricket ground Job application surge – and sees regular county matches, alongside the England cricket team for Birmingham, UK international or test matches. My creative and digital district, the Custard I’ve continued to refine Factory, is buzzing with artists, innovators, developers, retailers, chefs and my Sales and Customer connoisseurs of music. Other key trades include manufacturing (largely Service skills, seeing a cars, motorcycles and bicycles), alongside engineering and services. rise in job applications of 34% and 29% between May 2018 2018 - 2019 2018 Education Skills and January 2019. 4 I have an international Launch of Birmingham Festivals – universities including the perspective, with Brummies Birmingham, UK University of Birmingham, Aston, hailing from around the world Newman and Birmingham City. -

West Midlands Schools

List of West Midlands Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbot Beyne School Staffordshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Alcester Academy Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Alcester Grammar School Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Aldridge -

3 the Fairways Litle Aston

3 The Fairways, Little Aston, B74 3UG Parker Hall Set in an exclusive gated development in the ● Executive Detached Residence ● Third En Suite & Family Bathroom The composite front door opens into Reception desirable Little Aston is The Fairways, a ● Highly Desirable Location on Exclusive ● Bedrooms with TV Power Supply & Aerial Hall having porcelain tiled flooring, oak and glass contemporary detached residence offering Secure Gated Development ● Peaceful Position on Private Lane staircase rising to the first floor with a window to executive accommodation, six double ● Outstanding Specification throughout ● Double Garage & Parking the side, understairs storage and under floor heating bedrooms and an idyllic location on this ● Two Spacious Reception Rooms ● South Facing Gardens which extends throughout the ground floor private road. Built in 2014 by the renowned ● Open Plan Dining & Living Kitchen ● Peaceful Location on Private Lane accommodation. Doors open into: luxury homebuilder Spitfire Homes, this ● Reception Hall, Utility & Cloakroom ● Well Placed for Amenities, Commuter beautifully presented property enjoys a wealth Dining Room 4.24 x 3.22m (approx 13‘10 x 10‘6) ● Six Superb Double Bedrooms Routes & Schools of accommodation finished to the highest Having a bay window to the front aspect and black ● Master with En Suite & Dressing Room ● 4 Years NHBC Warranty Retained specification including a Poggenpohl kitchen, American walnut flooring matching the property’s ● Villeroy & Boch bathrooms, black American Bedroom Two Dressing Room & En Suite internal doors walnut doors, brushed aluminium sockets and switches an oak and glass staircase, with contemporary finishes including under floor heating to the ground floor, 5 amp sockets and Cat 6 cabling . -

Newtown, Oscott, Perry Barr, Soho, Oldbury

Equality and Diversity Strategy ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH ASTON, HANDSWORTH, JEWELLERY QUARTER, LOZELLS, NECHELLS, NEWTOWN, OSCOTT, PERRY BARR, SOHO, OLDBURY, ROWLEY REGIS, TIPTON, SMETHWICK, WEST BROMWICH C5206 GUJARATI Translation 1A ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú C5206Wef\h ^Af¶ Pf]h A¶ef$ ½Zz¡PþTf #alò #eUf\e Kf¶z\þVeüT TpW[ U[ VeüT A¶[]e z]þTpPhFrench A¶[ef .................... TranslationC5206 1A BENGALI SiTranslation vous ne 1Apouvez pas lire le document ci-joint, veuillez demander Translation 1B C5206àIf youquelqu'un can not read qui the parle attached anglais document, d'appeler please get ce someone numéro who pour speaks obtenir EnglishPolish deto ring l’aidethis number ………………………… for help ………………………… ùf PYf #e `eQf WhMf¶\ R¶ÀPe]fHÌ T ]epFh ^A¶ef, Pef Ao¶Ue A¶[l YR¶R¶ Yfb]]e YeKf¶ #pCyfú TranslationåKAeM^Wef\h ^Af¶ svzuË Pf]h 1B1A A¶ef$ kAgj-pñAif^ ½Zz¡PþTf &U[ ÁpiM^ HÌOe]f\e pxew^ Kf¶z\þVeüT Mo pArel^, TpW[ U[ áMugòh VeüT A¶[]e ker^ z]þTpPhsAhAezù^r A¶[ef. jMù éver^jI blew^ pAer^M åmM kAõek^ if^ey^ ............................... -

25 Little Aston Lane, Little Aston, Sutton Coldfield B74 3UA

25 Little Aston Lane, Little Aston, Sutton Coldfield B74 3UA 25 Little Aston Lane Little Aston Sutton Coldfield B74 3UA This well-presented character four bedroom detached family home is delightfully positioned overlooking Aston Wood Golf course with views of Lichfield beyond and has been enhanced to create impressive and spacious living accommodation. The property presents a natural ambience . The ground floor features two generous size reception rooms and a superb contemporary ‘urban’ style fitted kitchen with integrated appliances which opens into a dining area. The first floor master bedroom boasts a cathedral style ceiling and is fitted with light oak fitted wardrobes. There are fitted wardrobes in bedroom t wo and stylishly presented bathroom facilities throughout. The property would be ideal for someone working from home as the 32’ detached garage comes complete with an office area with kitchenette and w.c/washroom. The garage is set back within the good sized southerly facing gardens which also have a raised vegetable patch. Local shopping amenities can be found on Little Aston Lane and Blake Street, popular sporting facilities are within easy reach and include Four Oaks Cricket Club and Little Aston Tennis Club. Header-F12 All measurements are i mperial with metric Description-F11 measurements in brackets: "DoubleClick Insert EPC" Ground Floor Accommodation Welcoming reception hall Guest Cloakroom Lounge 17’ x 10’ 10 (5.18 x 3.30) Family room 14’ 6 x 9’ 9 (4.42 x 2.97) Breakfast kitchen with dining area 28’ 5 x 11’ 10 (8.66 x 3.61) First Floor Accommodation Master bedroom 22’ 10 max x 12’ 5 max (6.96 x 3.78) Wash room Travel links Bedroom two 12’ 11 x 11’ 10 (3.94 x 3.35) Blake Street Station is located within 0.5 miles from 25 Little Aston Lane offering parking facilities and links to Lichfield City and Birmingham City. -

Perry Barr Profile (Birmingham)

PERRY BARR PROFILE (BIRMINGHAM) DEMOGRAPHICS EDUCATION King Edwards VI Handsworth Arena Academy Grammer for Boys Academy Converter - Mainstream Academy Converter -Mainstream Total Population: 107,090 residents Working age population: 68,769 residents Eden Boys School Aged Under 16: 25,175 residents King Edwards VI Handsworth Free School Mainstream Grammer for Girls Aged 65+: 13,146 residents Academy Converter - Mainstream Gender Cardinal Wiseman Catholic School Male : 52,899 (49.4%) residents Voluntary Aided School Mayfield School Female: 54,191 (50.6%) residents Community Special School Ethnicity Great Barr Academy Academy Converter - Mainstream White : 40% Oscott Manor School Community Special School Mixed/Multiple Ethnic Groups: 4% Asian/Asian British: 39% Black/Black British: 15% Hamstead Hall Acaademy Priestly Smith School Other: 2% Academy Converter - Mainstream Community Special School 37 of the 66 neighbourhoods in Perry Barr in the bottom 20 of most deprived Handsworth Wood Girls Academy Academy Converter - Mainstream St John Wall Catholic School Voluntary Aided School EMPLOYMENT Data Sources: Constituency Resident Qualifications Demographics: Census Boundary 2011; GOV.UK: Jobs: 37,185 (54%) of residents in KS4 Schools IMD: English Indices of employment Multiple Deprivation Strategic 2013; Full-time employment UKCES Skills Survey -3.5% Companies 2015 – Skills Lacking in 25,404 (68.3%) UK Average: 71.8% 16 Year Olds; GOV.UK: Destinations of Key Stage 4 and Key Part-time employment Stage 5 Pupils 2015; 11,781 (31.7%) +2.9% KEY STAGE 4 DESTINATIONS Education: DfE 2016, UK Average: 28.2% Schools, Pupils and their Characteristics; • Sustained education destinations (90%) Unemployed Resident Qualifications: • Sustained employment/ destination (2%) 7,244 (10.5%) Census 2011; • FE Colleges (36%) UK Average: 7.6% +2.9% Employment: Census • Apprenticeships (4%) 2011 • State-funded sixth form (38%) BUSINESS – 111 STRATEGIC COMPANIES No Company Name Major Sector No Company Name Major Sector P.U. -

145 / 145A Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich / Wychbold

145 / 145A Rubery - Longbridge - Bromsgrove - Droitwich / Wychbold Diamond Bus The information on this timetable is expected to be valid until at least 19th October 2021. Where we know of variations, before or after this date, then we show these at the top of each affected column in the table. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service 145 145A 145 145A 145 145A 145 145A 145 145 145 145 Notes BAA BAA Rubery, Supermarket 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 § Rubery, after Ashill Road 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 § Rednal, o/s Colmers Farm School 1032 1132 1232 1332 1432 § Rednal, Cliff Rock Road (Opposite 2) 1032 1132 1232 1332 1432 § Rednal, Ryde Park Road (Opposite 3) 1033 1133 1233 1333 1433 § Longbridge, Longbridge Island (Stop LA) 1034 1134 1234 1334 1434 § Longbridge, Bristol Road South (Stop LE) 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 Longbridge, Longbridge Station (Stop LH) 0750 0936 1036 1136 1236 1336 1436 1500 1656 1726 1816 § Longbridge, Bristol Road South (Stop LF) 0750 0936 1036 1136 1236 1336 1436 1500 1656 1726 1816 § Longbridge, Longbridge Technology Park (Stop LB) 0751 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1501 1657 1727 1817 § Longbridge, Longbridge Island (After 6) 0752 0938 1038 1138 1238 1338 1438 1502 1658 1728 1818 § Rednal, Tinmeadow Crescent (Opposite 2) 0753 0939 1039 1139 1239 1339 1439 1503 1659 1729 1819 § Rednal, Low Hill Lane (Adjacent 2) 0754 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1504 1700 1730 1820 § Rednal, adj Parsonage Drive 0755 0941 1041 -

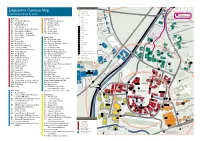

Edgbaston Campus Map (PDF)

Key utes min 15 G21 Edgbaston Campus Map Y2 Building name Information point Oakley Court SOMER SET ROAD Index to buildings by zone Level access entrance The Vale Footpath Steps Medical Practice B9 The Elms and Dental Centre Day Nursery Red Zone Orange Zone P Visitors car park Tennis Court R0 The Harding Building O1 The Guild of Students H Hospital D G20 A R1 Law Building O2 St Francis Hall 24 24 hour security O Pritchatts House R Bus stops RD R2 Frankland Building O3 University House A Athletics Track HO R G19 Library Ashcroft U R3 Hills Building O4 Ash House RQ Park House AR Museum HA R4 Aston Webb – Lapworth Museum O5 Beech House F L U A Pritchatts Park N Q A Sport facilities C Village R R5 Aston Webb – B Block P M O6 Cedar House A R A H F G I First aid T IN M R6 Aston Webb – Great Hall C R O7 Sport & Fitness E 13 Pritchatts Road I B GX H D D Food and drink The Spinney A N Environmental G18 Priorsfield A G R7 Aston Webb – Student Hub T R T E Research Facility B T S Retail ES A C R8 Physics West Green Zone R R S O T Toilets O W A O R9 Nuffield G1 32 Pritchatts Road N D G5 Lucas House Hotel ATM P G16 Pritchatts Road P R10 Physics East G2 31 Pritchatts Road A Car Park R Canal bridge K Conference R11 Medical Physics G3 European Research Institute R Park s G14 O Sculpture trail inute R12 Bramall Music Building G4 3 Elms Road B8 10 m Garth House A G4 D R13 Poynting Building G5 Computer Centre Rail G15 Westmere R14 Barber Institute of Fine Arts Lift G6 Metallurgy and Materials D B6 A Electric Vehicle Charge Point B7 Edgbaston R15 Watson Building -

Ladywood District Jobs and Skills Plan 2015 Overview of Ladywood District1

Ladywood Jobs and Skills Plan Ladywood District Jobs and Skills Plan 2015 Overview of Ladywood District1 Ladywood District covers the majority of the city centre, along with inner city areas to the north and east. It is composed of 4 wards – Aston, Ladywood, Nechells and Soho. Much of the district experiences some very challenging conditions in terms of labour market status, with very high levels of unemployment. But this contrasts with the city centre area – the east of Ladywood ward, and the south-west of Nechells ward – where unemployment and deprivation levels are low. Ladywood has a younger age profile to the city centre with a higher proportion of under 40s and fewer over 45s. Overall the proportion of working age adults (70%) is well above the city average (64%). The proportion rises to 84% in Ladywood ward, but is close to the city average in the other 3 wards. There are 23,828 residents aged 18-24 equating to 19% of the population, compared to 12 % for Birmingham, driven at least in part by large numbers of students. The ethnic profile of the working age population in the district differs to that of the city, with a much lower proportion of white working age residents (32%) compared to the city average (59%). But this masks ward variations, with the proportion only 15% in Aston, 23% in Soho and 31% in Nechells wards, but much closer to the city average at 52% in Ladywood ward. Overall, the largest non-white groups are Pakistani (13%) and Black Caribbean (9%). The Pakistani group forms 20% of the population in Aston and 16% in Nechells and Soho wards ,but only 3% in Ladywood ward. -

Candidates West Midlands

Page | 1 LIBERAL/LIBERAL DEMOCRAT CANDIDATES in PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS in the WEST MIDLAND REGION 1945-2015 ALL CONSTITUENCIES WITHIN THE COUNTIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE SHROPSHIRE STAFFORDSHIRE WARWICKSHIRE WORCESTERSHIRE INCLUDING SDP CANDIDATES in the GENERAL ELECTIONS of 1983 and 1987 COMPILED BY LIONEL KING 1 Page | 2 PREFACE As a party member since 1959, based in the West Midlands and a parliamentary candidate and member of the WMLF/WMRP Executive for much of that time, I have been in the privileged position of having met on several occasions, known well and/or worked closely with a significant number of the individuals whose names appear in the Index which follows. Whenever my memory has failed me I have drawn on the recollections of others or sought information from extant records. Seven decades have passed since the General Election of 1945 and there are few people now living with personal recollections of candidates who fought so long ago. I have drawn heavily upon recollections of conversations with older Liberal personalities in the West Midland Region who I knew in my early days with the party. I was conscious when I began work, twenty years ago, that much of this information would be lost forever were it not committed promptly to print. The Liberal challenge was weak in the West Midland Region over the period 1945 to 1959 in common with most regions of Britain. The number of constituencies fought fluctuated wildly; 1945, 21; 1950, 31; 1951, 3; 1955 4. The number of parliamentary constituencies in the region averaged just short of 60, a very large proportion urban in character.