Historical Overview of Transplantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

Flesh Is Heir

cover story 125 Years of r e m o v i n g a n d Preventing t h e i l l s t o w h i c h fleSh is heiR b y b arbara I. Paull, e r I c a l l o y d , e d w I n K I ester Jr., J o e m ik s c h , e l a I n e v I t o n e , c h u c K s ta r e s I n I c , a n d sharon tregas ki s lthough the propriety of establishing a medical school here has been sharply questioned by some, “ we will not attempt to argue the question. Results will determine whether or not the promoters of the enterprise were mistaken in their judgment Aand action. The city, we think, offers ample opportunity for all that is desirable in a first-class medical school, and if you will permit me to say it, the trustees and faculty propose to make this a first-class school.” —John Milton Duff, MD Professor of Obstetrics, September 1886 More than three decades after the city’s first public hospital was established, after exhausting efforts toward a joint charter, Pittsburgh physicians founded an indepen- dent medical college, opening its doors in September 1886. This congested industrial city—whose public hospital then performed more amputations and saw more fatal typhoid-fever cases per capita than any other in the country—finally would have its own pipeline of new physicians for its rising tide of diseased and injured brakemen, domestics, laborers, machinists, miners, and steelworkers from around the world, as well as the families of its merchants, professionals, and industry giants. -

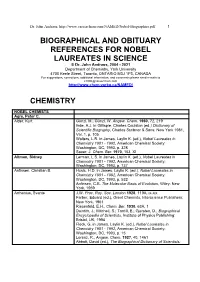

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

35Th Anniversary Vol

Published for Members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 35th Anniversary Vol. XV, No. 1 Summer 2009 President’s Letter 4 Member News 6 Regulatory & Reimbursement 8 Legislative Report 10 OPTN/UNOS Corner 12 35th Anniversary of ASTS 14 Winter Symposium 18 Chimera Chronicles 19 American Transplant Congress 2009 20 Beyond the Award 23 ASTS Job Board 26 Corporate Support 27 Foundation 28 Calendar 29 New Members 30 www.asts.org ASTS Council May 2009–May 2010 PRESIDENT TREASURER Charles M. Miller, MD (2011) Robert M. Merion, MD (2010) Alan N. Langnas, DO (2012) Cleveland Clinic Foundation University of Michigan University of Nebraska Medical Center 9500 Euclid Avenue, Mail Code A-110 2922 Taubman Center PO Box 983280 Cleveland, OH 44195 1500 E. Medical Center Drive 600 South 42nd Street Phone: 216 445.2381 Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5331 Omaha, NE 68198-3280 Fax: 216 444.9375 Phone: 734 936.7336 Phone: 402 559.8390 Email: [email protected] Fax: 734 763.3187 Fax: 402 559.3434 Peter G. Stock, MD, PhD (2011) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] University of California San Francisco PRESIDENT -ELECT COUNCILORS -AT -LARGE Department of Surgery, Rm M-884 Michael M. Abecassis, MD, MBA (2010) Richard B. Freeman, Jr., MD (2010) 505 Parnassus Avenue Northwestern University Tufts University School of Medicine San Francisco, CA 94143-0780 Division of Transplantation New England Medical Center Phone: 415 353.1551 675 North St. Clair Street, #17-200 Department of Surgery Fax: 415 353.8974 Chicago, IL 60611 750 Washington Street, Box 40 Email: [email protected] Phone: 312 695.0359 Boston, MA 02111 R. -

Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: the Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 2 2007 Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: The Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation Neal R. Barshes Carl S. Hacker Richard B. Freeman Jr. John M. Vierling John A. Goss Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation Neal R. Barshes, Carl S. Hacker, Richard B. Freeman Jr., John M. Vierling & John A. Goss, Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: The Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation, 23 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y 200 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol23/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, AND THE TRANSPLANT CLINICIAN: THE ETHICAL AND LEGISLATIVE BASIS OF A NATIONAL POLICY ON DONOR LIVER ALLOCATION Neal R. Barshes,* Carl S. Hacker,**Richard B. Freeman Jr.,**John M. Vierling,****& John A. Goss***** INTRODUCTION Like many other valuable health care resources, the supply of donor livers in the United States is inadequate for the number of patients with end-stage liver disease in need of a liver transplant. The supply- demand imbalance is most clearly demonstrated by the fact that each year approximately ten to twelve percent of liver transplant candidates die before a liver graft becomes available.1 When such an imbalance between the need for a given health care resource and the supply of that resource exists, some means of distributing the resource must be developed. -

St Med Ita.Pdf

Colophon Appunti dalle lezioni di Storia della Medicina tenute, per il Corso di Laurea in Medicina e Chirurgia dell'Università di Cagliari, dal Professor Alessandro Riva, Emerito di Anatomia Umana, Docente a contratto di Storia della Medicina, Fondatore e Responsabile del Museo delle Cere Anatomiche di Clemente Susini Edizione 2014 riveduta e aggiornata Redazione: Francesca Testa Riva Ebook a cura di: Attilio Baghino In copertina: Francesco Antonio Boi, acquerello di Gigi Camedda, 1978 per gentile concessione della Pinacoteca di Olzai Prima edizione online (2000) Redazione: Gabriele Conti Webmastering: Andrea Casanova, Beniamino Orrù, Barbara Spina Ringraziamenti Hanno collaborato all'editing delle precedenti edizioni Felice Loffredo, Marco Piludu Si ringraziano anche Francesca Spina (lez. 1); Lorenzo Fiorin (lez. 2), Rita Piana (lez. 3); Valentina Becciu (lez. 4); Mario D'Atri (lez. 5); Manuela Testa (lez. 6); Raffaele Orrù (lez. 7); Ramona Stara (lez. 8), studenti del corso di Storia della Medicina tenuto dal professor Alessandro Riva, nell'anno accademico 1997-1998. © Copyright 2014, Università di Cagliari Quest'opera è stata rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 4.0 Internazionale. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Data la vastità della materia e il ridotto tempo previsto dagli attuali (2014) ordinamenti didattici, il profilo di Storia della medicina che risulta da queste note è, ovviamente, incompleto e basato su scelte personali. Per uno studio più approfondito si rimanda alle voci bibliografiche indicate al termine. Release: riva_24 I. La Medicina greca Capitolo 1 La Medicina greca Simbolo della medicina Nelle prime fasi, la medicina occidentale (non ci occuperemo della medicina orientale) era una medicina teurgica, in cui la malattia era considerata un castigo divino, concetto che si trova in moltissime opere greche, come l’Iliade, e che ancora oggi è connaturato nell’uomo. -

The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1969 The tS ory of Organ Transplantation J. Englebert Dunphy Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. Englebert Dunphy, The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J. 67 (1969). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Story of Organ Transplantation By J. ENGLEBERT DUNmHY, M.D.* THE successful transplantation of a heart from one human being to another, by Dr. Christian Barnard of South Africa, hias occasioned an intense renewal of public interest in organ transplantation. The back- ground of transplantation, and its present status, with a note on certain ethical aspects are reviewed here with the interest of the lay reader in mind. History of Transplants Transplantation of tissues was performed over 5000 years ago. Both the Egyptians and Hindus transplanted skin to replace noses destroyed by syphilis. Between 53 B.C. and 210 A.D., both Celsus and Galen carried out successful transplantation of tissues from one part of the body to another. While reports of transplantation of tissues from one person to another were also recorded, accurate documentation of success was not established. John Hunter, the father of scientific surgery, practiced transplan- tation experimentally and clinically in the 1760's. Hunter, assisted by a dentist, transplanted teeth for distinguished ladies, usually taking them from their unfortunate maidservants. -

Advances and Controversies in an Era of Organ Shortages M I Prince, M Hudson

135 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.917.135 on 1 March 2002. Downloaded from REVIEW Liver transplantation for chronic liver disease: advances and controversies in an era of organ shortages M I Prince, M Hudson ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:135–141 Since liver transplantation was first performed in 1968 diminished (partially due to improvements in by Starzl et al, advances in case selection, liver surgery, road safety), resulting in the number of potential recipients for liver transplantation exceeding anaesthetics, and immunotherapy have significantly organ supply with attendant deaths of patients on increased the indications for and success of this waiting lists. We review areas of controversy and operation. Liver transplantation is now a standard new approaches developing in response to this mismatch. therapy for many end stage liver disorders as well as acute liver failure. However, while demand for IMPROVING THE RATIO OF TRANSPLANT SUPPLY AND DEMAND cadaveric organ grafts has increased, in recent years There are three approaches to improving the ratio the supply of organs has fallen. This review addresses of liver availability to potential recipients. First, to current controversies resulting from this mismatch. In maximise efficiency of liver distribution between centres; second, to examine ways of expanding particular, methods for increasing graft availability and the donor pool; and third, to impose limits on use difficulties arising from transplantation in the context of of livers for certain indications. Xenotransplanta- alcohol related cirrhosis, primary liver tumours, and tion is not currently an option for human liver transplantation. hepatitis C are reviewed. Together these three Organ distribution protocols minimise in- indications accounted for 42% of liver transplants equalities in supply and demand between regions performed for chronic liver disease in the UK in 2000. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Journal of Surgery Goss MB, Et Al

Journal of Surgery Goss MB, et al. J Surg: JSUR-1160. Review Article DOI: 10.29011/2575-9760.001160 Expansion of the Pediatric Donor Pool for Liver Transplantation in the United States Matthew B. Goss, Michael L. Kueht, Nhu Thao Nguyen Galvan, Christine Ann O’Mahony, Ronald Timothy Cotton, Abbas Rana* Department of Surgery, Division of Abdominal Transplantation, Michael E. DeBakey, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA *Corresponding author: Abbas Rana, Department of Surgery, Division of Abdominal Transplantation, Michael E. DeBakey, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, MS: BCM390, Houston, Texas 77030, USA. Tel: +17133218423; Fax: +17136102479; Email: [email protected] Citation: Goss MB, Kueht ML, Galvan NTN, O’Mahony CA, Cotton RT, et al. (2018) Expansion of the Pediatric Donor Pool for Liver Transplantation in the United States. J Surg: JSUR-1160. DOI: 10.29011/2575-9760.001160 Received Date: 31 July, 2018; Accepted Date: 10 August, 2018; Published Date: 17 August, 2018 Abstract As the greatest survival benefit owing to Orthotopic Liver Transplantation (OLT) is achieved in the pediatric population (< 18 years of age), the United States (US) annual unmet need of more than 100 pediatric liver allografts warrants an innovative approach to reduce this organ deficiency. We present a three-pronged strategy with the potential to eliminate the disparity between supply and demand of pediatric liver allografts: (1) optimize the current supply of donor livers, (2) further capitalize on technical variant allografts from cadaveric and living donation, and (3) implement a novel donation approach, termed ‘Imminent Death Donation’ (IDD), allowing for donation of the left lateral segment prior to life support withdrawal in patients not meeting brain death criterion. -

1 2002 Presidential Address to the American Society of Transplant

1 2002 Presidential Address to the American Society of Transplant Surgeons “Transplantation; Looking Back to the Future” Friends and Colleagues: I stand before you feeling tremendous pride in our organization, and the honor to serve as your President this past year has been one of the highlights of my professional career. Like you, I have listened, usually politely, to many addresses given by outgoing Presidents over the years. They are usually interesting, and some have been inspiring. Some have been educational, some have been tedious, some have been boring, and some have been quite controversial. Until a year ago, I thought little about how my predecessors arrived at their subject. As you know, there are no rules, the topic is open ended, and obviously there is no prospective peer review. However, there is a form of peer review that comes immediately at the conclusion; …at least for a few minutes during the inevitable post delivery critique, and believe me…it is that daunting thought which has occupied a substantial amount of my time, at least recently. Now that it is my turn to stand before you, I have also learned, THANKFULLY, that few of you will remember a word of what I say… …except those of you who are also afforded the great honor to serve as President… You will remind yourself when you read each prior address, as you struggle to identify a worthy subject when your turn comes…. and that it will!! For a couple of reasons, I will spend a few minutes describing some personal reflections on my path to this day… First, for the young in the audience, perhaps this may encourage one of you to select a career that will be as exciting and rewarding for you as mine for me … and 2 Second, it allows me an opportunity to publicly thank some of the people who have been especially important to me during this journey. -

The Legacy of Tom Starzl Is Alive and Well in Transplantation Today1

The Legacy of Tom Starzl Is Alive and Well in Transplantation Today1 JAMES F. MARKMANN Chief, Division of Transplant Surgery Co-Director, Center for Transplantation Sciences Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital Claude E. Welch Professor, Harvard Medical School Introduction It is an honor to celebrate the life and career of Dr. Thomas Starzl with the American Philosophical Society. As Dr. Clyde Barker so elegantly summarized in his talk, “Tom Starzl and the Evolution of Transplanta- tion,”2 Dr. Starzl was a larger-than-life figure whose allure drew young surgeons to the field of liver transplantation and spurred them to careers as surgeon-scientists. Dr. Starzl’s impact still lives on today through those he inspired and by the influence of his body of work. To illustrate the enduring nature of his scientific contributions, I will review three areas of active transplant research that have the potential to radically advance the field, which connect with foundational work by Dr. Starzl. The compendium of Dr. Starzl’s work, with over 2,200 scientific papers, 300 books and chapters, 1,300 presentations, and hundreds of trainees, far exceeds even the most prolific efforts of other contributors to transplantation; corroborating his preeminence in the field, in 1999 he was identified as the most cited scientist in all of clin- ical medicine.3 It was a relatively simple task to find robust threads of his early investigations in the advances of today because his work permeates nearly every aspect of the field. The areas of work on which I will focus seek to address the two primary challenges facing the field of transplantation—the need for toxic lifelong immunosuppression to prevent allograft rejection, and an inadequate organ supply to treat all those who would benefit from organ replacement.