Introduction Bakhtin, "Discourse in the Novel," P. 355. 3. Yaeger, "A Fire In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poétique De La Mémoire Dans Hiroshima, Mon Amour

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL POÉTIQUE DE LA MÉMOIRE DANS HIROSHIMA, MON AMOUR MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAIRES PAR MAGALI BLEIN Juin 2007 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Au terme du présent mémoire, je désire témoigner toute ma gratitude à ma directrice de recherches, Mille Johanne Villeneuve, pour ses conseils judicieux, sa disponibilité, sa rigueur et sa patience. La pertinence et la qualité de ses corrections auront permis de rehausser la valeur de ce travail. -

La Coalescencia Literario-Cine

Publicado en: Lourdes Carriedo, Mª Dolores Picazo y Mª Luisa Guerrero (eds.), Entre escritura e imagen. Lecturas de narrativa contemporánea. Bruselas, Peter Lang, pp. 245-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0352-6392-3 ISBN: 978-3-0352-6392-3 La coalescencia literario-cinematográfica en la obra de Marguerite Duras Lourdes Monterrubio Ibáñez Universidad Complutense de Madrid El trabajo de Marguerite Duras, único en la creación de un espacio literario- cinematográfico nuevo, fértil e inabarcable en sus múltiples posibilidades, genera una nueva materia literario-cinematográfica a la que hace referencia el título de este artículo, donde el texto literario escribe con la imagen. En uno de los textos recogidos en Les Yeux verts, y hablando sobre Aurélia Steiner (1979), uno de los colaboradores de Cahiers du cinéma se expresa en los siguientes términos a propósito de cómo la voz, la voz de Duras, va creando el personaje de Aurélia: Le terme qui conviendrait mieux serait peut-être coalescence, osmose. On imagine mal que quelqu’un d’autre puisse dire ce texte. Tu étais Aurélia Steiner en même temps que tu l’écrivais et que tu le lisais. Tu es Aurélia Steiner. On ne pense pas : c’est Marguerite Duras. Je ne vois pas quelqu’un d’autre que toi pouvant proférer ce texte. C’est peut-être un leurre (Duras, 1996: 151). Ósmosis y coalescencia, estos son los términos a partir de los cuales desarrollaremos la definición y caracterización de la obra literario-cinematográfica de Marguerite Duras. La definición de la Real Academia Española de la Lengua de ambos términos es la siguiente: Ósmosis: 1. -

Download This PDF File

Dominiek Hoens & Sigi Jöttkandt INTRODUCTION ‘Lacan is not all’1 xpressed with the simplicity of her elliptical put-down which we have adopted for our title for this special issue, Marguerite Duras’ attitude to- wards psychoanalysis was ambiguous to say the least.1 Frequently, when she speaks of psychoanalysis, she leaves us in no doubt of her very great Emistrust of it, her acute sense of being a stranger to its discourse. Yet, regarding the event that inspired these invitations to express her opinion on psychoanalysis – Jacques Lacan’s “Homage to Marguerite Duras, on Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein,” – she is generally positive, at times even enthusiastic.2 Since its first appearance in 1965, Lacan’s sibylline essay has provoked a flood of commentaries and further explorations of the topics it alludes to: love, desire, femi- ninity, writing, among many others. Therefore, it seems natural to us to launch this issue with Jean-Michel Rabaté’s essay on The Ravishing of Lol V. Stein, the pivotal novel in Duras’ oeuvre and the text that originally sparked the Lacanian interest in Duras. In his candid contribution, Rabaté raises the issue of ravissement, starting from his question, “Why were we all in love with Marguerite Duras?” This ‘all,’ we discover, may first and foremost include Lacan, whose “Homage” entails an analy- sis of his own ravishment by Duras or, more precisely, by the unfolding triangles in Lol V. Stein that end up encompassing the reader. It is for this reason that, even as he pays careful, ‘academic’ attention to the ternaries inside, yet transgressing, the confines of the novel, Rabaté also cannot refrain from a ‘personal’ questioning of the triangle that was constituted by Duras, her work and himself, as he recalls in this intimate memoir recounting the remarkable times that they spent together in Dijon, and later, in Paris in the 1970s and 1980s. -

MARGUERITE DURAS (1914-1996) Bibliographie Des Ouvrages Disponibles En Libre-Accès

Bibliothèque nationale de France direction des collections département Littérature et art Avril 2014 CENTENAIRE DE MARGUERITE DURAS (1914-1996) Bibliographie des ouvrages disponibles en libre-accès Écrire c’est aussi ne pas parler. C’est se taire. C’est hurler sans bruit. (Écrire, 1993) De son vrai nom Marguerite Donnadieu, Marguerite Duras est née le 4 avril 1914 à Saïgon, alors en Indochine française, d'une mère institutrice et d'un père professeur de mathématiques qui meurt en 1921. Elle s’installe en France en 1932, épouse Robert Antelme en 1939, et publie son premier roman, Les Impudents, en 1943, sous le pseudonyme de Marguerite Duras. Résistante pendant la guerre, communiste jusqu'en 1950, participante active à Mai 68, c’est une femme profondément engagée dans les combats de son temps, passionnée, volontiers provocante, et avec aussi ses zones d’ombres. Elle est un temps rattachée au mouvement du Nouveau Roman, même si son écriture demeure très singulière, de par sa musique faite de répétitions et de phrases déstructurées, de trivialité et de lyrisme mêlés. Les thèmes récurrents de ses romans se dégagent très tôt : l'attente, l'amour, l’écriture, la folie, la sexualité féminine, l'alcool, notamment dans Moderato cantabile (1958), Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964), Le Vice-Consul (1966). Elle écrit aussi pour le théâtre et pour le cinéma. Dans tous ces domaines c’est une créatrice novatrice, et de ce fait souvent controversée. Elle rencontre assez tardivement un immense succès mondial, qui fait d’elle l'un des écrivains vivants les plus lus, avec L'Amant, Prix Goncourt en 1984. -

Speaking Through the Body

DE LA DOULEUR À L’IVRESSE: VISIONS OF WAR AND RESISTANCE Corina Dueñas A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (French). Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dominique Fisher Reader: Martine Antle Reader: Hassan Melehy Reader: José M. Polo de Bernabé Reader: Donald Reid © 2007 Corina Dueñas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CORINA DUEÑAS: De la douleur à l’ivresse: Visions of War and Resistance (Under the direction of Dominique Fisher) This dissertation explores the notion of gendered resistance acts and writing through close readings of the personal narratives of three French women who experienced life in France during the Second World War. The works of Claire Chevrillon (Code Name Christiane Clouet: A Woman in the French Resistance), Marguerite Duras (La Douleur), and Lucie Aubrac (Ils partiront dans l’ivresse) challenge traditional definitions of resistance, as well as the notion that war, resistance and the writing of such can be systematically categorized according to the male/female dichotomy. These authors depict the day-to-day struggle of ordinary people caught in war, their daily resistance, and their ordinary as well as extraordinary heroism. In doing so, they debunk the stereotypes of war, resistance and heroism that are based on traditional military models of masculinity. Their narratives offer a more comprehensive view of wartime France than was previously depicted by Charles de Gaulle and post-war historians, thereby adding to the present debate of what constitutes history and historiography. -

Reassessing Marguerite Duras

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 26 Issue 1 Perspectives in French Studies at the Article 7 Turn of the Millennium 1-1-2002 Reassessing Marguerite Duras Carol J. Murphy University of Florida-Gainesville Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Murphy, Carol J. (2002) "Reassessing Marguerite Duras," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 26: Iss. 1, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1521 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reassessing Marguerite Duras Abstract Since her death on March 3, 1996, Marguerite Duras continues to "live on" through the ongoing critical appreciation of her works… Keywords death, "March 3, 1996", Marguerite Duras, appreciation, critical analysis This article is available in Studies in 20th Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol26/iss1/7 Murphy: Reassessing Marguerite Duras Reassessing Marguerite Duras Carol J. Murphy University of Florida-Gainesville Since her death on March 3, 1996, Marguerite Duras continues to "live on" through the ongoing critical appreciation of her works. Numerous collections of essays have been published since 1996, some in direct homage to her passing, like the special issues of the NRF (1998) and the Cahiers Renaud Barrault (1996), per- sonal testimonies such as L'Amie (1997) (The Friend') by Michele Manceaux, photo albums, biographies (and repeat biographies2), others, more coincidental, like Duras, Lectures plurielles (1998) (Duras, Plural Readings), the proceedings of a colloquium on Duras held in London just before her death, and still others, like the special Fall 1999 issue of Dalhousie French Studies. -

Alain Resnais' and Marguerite Duras' Hiroshima Mon Amour

Sarah French, From History to Memory SARAH FRENCH From History to Memory: Alain Resnais’ and Marguerite Duras’ Hiroshima mon amour Abstract This paper examines the representation of history and memory in Alain Resnais’ and Marguerite Duras' 1959 film Hiroshima mon amour. It argues that the film’s privileging of subjective remembrance reflects a broader cultural interest in using memory as a counter discourse to established history. The widely documented cultural preoccupation with memory became particularly prominent in the early 1980s. However, Hiroshima mon amour can be read as an important early example of a film that pre- dates the contemporary ‘memory boom’. For Resnais and Duras, the magnitude of the devastation in Hiroshima exceeds the limits of filmic representation. Their solution to the problem that the historic event is unrepresentable is to approach the event indirectly while focusing on an individual traumatic memory. Through a close analysis and critique of the film I argue that the film’s emphasis on individual memory validates the legitimacy of the personal narrative but problematically subsumes the political events and displaces history from the discursive realm. I also suggest that problems emerge in the film’s depiction of its traumatised female subject. While Hiroshima mon amour represents a complex female subjectivity and interiority, the process of remembrance depicted deprives the woman of agency and renders her trapped within a compulsive repetition of the past. Hiroshima mon amour (1959), written by Marguerite Duras and directed by Alain Resnais, explores the ethical implications of memory, mourning and witnessing in relation to the filmic representation of traumatic events. -

Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo

Re-thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo Regina F. Bartolone A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Dr. Martine Antle (advisor) Dr. Marsha Collins (reader) Dr. Maria DeGuzmán (reader) Dr. Dominque Fisher (reader) Dr. Diane Leonard (reader) Abstract Regina F.Bartolone Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo (Under the direction of Dr. Martine Antle) This dissertation is a cross-cultural examination of the creation and the socio- cultural implications of the languages of pain in the works of French author, Marguerite Duras and Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo. Recent studies have determined that discursive communication is insufficient in expressing one’s pain. In particular, Elaine Scarry maintains that pain destroys language and that its victims must rely on the vocabulary of other cultural spheres in order to express their pain. The problem is that neither Scarry nor any other Western pain scholar can provide an alternative to discursive language to express pain. This study claims that both artists must work beyond their own cultural registers in order to give their pain a language. In the process of expressing their suffering, Duras and Kahlo subvert traditional literary and artistic conventions. Through challenging literary and artistic forms, they begin to re-think and ultimately re-define the way their readers and viewers understand feminine subjectivity, colonial and wartime occupation, personal tragedy, the female body, Christianity and Western hegemony. -

No. 260 Romane Fostier. Marguerite Duras. Paris

H-France Review Volume 19 (2019) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 19 (December 2019), No. 260 Romane Fostier. Marguerite Duras. Paris : Gallimard, collection Folio biographies (n° 146), 2018. 304 pages + dossier photographique de 8 pages. Repères chronologiques et références bibliographiques (œuvres de Marguerite Duras et biographies). 9,40€. ISBN : 9782072694073. Compte-rendu par Catherine Rodgers, Swansea University. De nombreuses biographies de Marguerite Duras ont été publiées, de la très critiquée Duras ou le poids d’une plume rédigée par Frédérique Dubelley, à la très sérieuse C’était Marguerite Duras de Jean Vallier, en passant par la très médiatisée Marguerite Duras de Laure Adler et les nombreux récits plus ou moins romancés d’Alain Vircondelet.[1] Celle de Jean Vallier fait deux volumes de 1669 pages et regorge de preuves et références, témoin de l’énorme travail de recherche entrepris. À de nombreuses reprises, l’auteur réfute les affirmations de Laure Adler et les conclusions un peu hâtives qu’elle tire par endroits. Il faut dire aussi que la qualité des résumés qu’Adler avait rédigés des œuvres de Duras s’amenuisait au cours du volume. La biographie de Jean Vallier est une excellente source d’informations pour les spécialistes de Duras, mais elle peut paraître rebutante pour le non-spécialiste car elle est longue et touffue. Il y avait donc un créneau à combler sur le marché pour une bonne biographie de Duras qui soit d’un accès facile et agréable à lire pour le grand public. Cela a sans doute été le raisonnement des éditions Gallimard pour la publication de ce volume dans la collection Folio biographie. -

She Said Destroy Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHE SAID DESTROY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nadia Bulkin | 264 pages | 20 Aug 2017 | Word Horde | 9781939905338 | English | none She Said Destroy PDF Book Just beyond, the woods, always the woods, a lure, a threat, a veil, a plot unfulfilled but tantalizing. Hide Spoilers. If you love mysteries and thrillers, get ready for dozens Jun 02, Steven rated it really liked it. Read Full Review. About Marguerite Duras. It was also a movie, and Duras's fictions have, of course, been filmed before, From the likes of Alain Resnais to Jules Dassin, but this was her first movie wholly her own, and she has come up with some surprises. No matter how much talk there is of gods and great magic, it cannot be filled with import in this broadly written and drawn outline of one of those stories that sounded like a good at the time. Silence Increasing heat. Only much, much less cute She Said Destroy 1 is a femme centered narrative about a resistance against a near omnipresent empire that combines magic and space travel with dreamy art to boot. Original Title. Here there is not any sounds present which we cannot locate by what we see, just the birds and sound of the men playing tennis, but the sound of the voices still does their tricks with us. I wanted to give it to him. I know I mentioned this book to him, said he might be into it given his background in theater and all that, and he told me that he had a copy of The Lover on his shelf. -

En Attendant Robert L. / La Douleur D'emmanuel Finkiel

Document generated on 09/28/2021 5:46 a.m. Ciné-Bulles En attendant Robert L. La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel Nicolas Gendron Dossier 50 ans depuis 1968 Volume 36, Number 3, Summer 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/88635ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Gendron, N. (2018). Review of [En attendant Robert L. / La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel]. Ciné-Bulles, 36(3), 8–11. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Du livre au lm La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel En attendant Robert L. NICOLAS GENDRON Par insatisfaction chronique ou exigence extrême, terand! —, elle échappe de peu à un guet-apens, ou quelque chose entre les deux, l’écrivaine alors que Robert est fait prisonnier politique et en- Marguerite Duras a presque toujours boudé les voyé au camp de Buchenwald. En reviendra-t-il? La adaptations de ses textes — romans ou scéna- Douleur témoigne de l’attente de Marguerite, rios — produites au cinéma, si l’on exclut la réussite jusqu’à la déraison. -

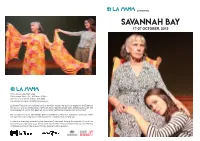

Savannah Bay 17-27 OCTOBER, 2019

presents savannah bay 17-27 OCTOBER, 2019 Office Phone: (03) 9347 6948 Office Hours: Mon – Fri | 10:30am – 5:30pm 349 Drummond Street, Carlton VIC 3053 www.lamama.com.au | [email protected] La Mama Theatre is on traditional land of the Kulin Nation. We give our respect to the Elders of this country and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people past, present and future. We acknowledge all events take place on stolen lands and that sovereignty was never ceded. We are grateful to all our philanthropic partners and donors, advocates, volunteers, audiences, artists and our entire community as we work towards the La Mama rebuild. Thank you! La Mama is financially assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council – its arts funding and advisory body, the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria, and the City of Melbourne through the Arts and Culture triennial funding program. MARGUERITE DURAS BRENDA PALMER savannah bay (Writer) (Madeleine) Written by Marguerite Duras Born in French Indochina, Marguerite Duras (1914- Brenda likes nothing better than trying to fathom under Directed by Laurence Strangio 1996) was one of the most significant 20th century Laurence’s direction the sometimes unfathomable literary figures in France. The author of many novels, Marguerite Duras – firstly L’Amante Anglaise, then Performed by Brenda Palmer and Annie Thorold plays, essays and screenplays, she is best known The Atlantic Man and The Lover (with Annie Thorold, Set design by Laurence Strangio outside France for her filmscript Hiroshima, mon twice!) and now Savannah Bay – and at her theatre (within the set design by Bronwyn Pringle for The Disappearing Trilogy) Amour (filmed by Alain Resnais in 1959) and her best- of choice, La Mama.