Reassessing Marguerite Duras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poétique De La Mémoire Dans Hiroshima, Mon Amour

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL POÉTIQUE DE LA MÉMOIRE DANS HIROSHIMA, MON AMOUR MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAIRES PAR MAGALI BLEIN Juin 2007 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Au terme du présent mémoire, je désire témoigner toute ma gratitude à ma directrice de recherches, Mille Johanne Villeneuve, pour ses conseils judicieux, sa disponibilité, sa rigueur et sa patience. La pertinence et la qualité de ses corrections auront permis de rehausser la valeur de ce travail. -

Speaking Through the Body

DE LA DOULEUR À L’IVRESSE: VISIONS OF WAR AND RESISTANCE Corina Dueñas A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (French). Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dominique Fisher Reader: Martine Antle Reader: Hassan Melehy Reader: José M. Polo de Bernabé Reader: Donald Reid © 2007 Corina Dueñas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CORINA DUEÑAS: De la douleur à l’ivresse: Visions of War and Resistance (Under the direction of Dominique Fisher) This dissertation explores the notion of gendered resistance acts and writing through close readings of the personal narratives of three French women who experienced life in France during the Second World War. The works of Claire Chevrillon (Code Name Christiane Clouet: A Woman in the French Resistance), Marguerite Duras (La Douleur), and Lucie Aubrac (Ils partiront dans l’ivresse) challenge traditional definitions of resistance, as well as the notion that war, resistance and the writing of such can be systematically categorized according to the male/female dichotomy. These authors depict the day-to-day struggle of ordinary people caught in war, their daily resistance, and their ordinary as well as extraordinary heroism. In doing so, they debunk the stereotypes of war, resistance and heroism that are based on traditional military models of masculinity. Their narratives offer a more comprehensive view of wartime France than was previously depicted by Charles de Gaulle and post-war historians, thereby adding to the present debate of what constitutes history and historiography. -

Alain Resnais' and Marguerite Duras' Hiroshima Mon Amour

Sarah French, From History to Memory SARAH FRENCH From History to Memory: Alain Resnais’ and Marguerite Duras’ Hiroshima mon amour Abstract This paper examines the representation of history and memory in Alain Resnais’ and Marguerite Duras' 1959 film Hiroshima mon amour. It argues that the film’s privileging of subjective remembrance reflects a broader cultural interest in using memory as a counter discourse to established history. The widely documented cultural preoccupation with memory became particularly prominent in the early 1980s. However, Hiroshima mon amour can be read as an important early example of a film that pre- dates the contemporary ‘memory boom’. For Resnais and Duras, the magnitude of the devastation in Hiroshima exceeds the limits of filmic representation. Their solution to the problem that the historic event is unrepresentable is to approach the event indirectly while focusing on an individual traumatic memory. Through a close analysis and critique of the film I argue that the film’s emphasis on individual memory validates the legitimacy of the personal narrative but problematically subsumes the political events and displaces history from the discursive realm. I also suggest that problems emerge in the film’s depiction of its traumatised female subject. While Hiroshima mon amour represents a complex female subjectivity and interiority, the process of remembrance depicted deprives the woman of agency and renders her trapped within a compulsive repetition of the past. Hiroshima mon amour (1959), written by Marguerite Duras and directed by Alain Resnais, explores the ethical implications of memory, mourning and witnessing in relation to the filmic representation of traumatic events. -

Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo

Re-thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo Regina F. Bartolone A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Dr. Martine Antle (advisor) Dr. Marsha Collins (reader) Dr. Maria DeGuzmán (reader) Dr. Dominque Fisher (reader) Dr. Diane Leonard (reader) Abstract Regina F.Bartolone Re-Thinking the Language of Pain in the Works of Marguerite Duras and Frida Kahlo (Under the direction of Dr. Martine Antle) This dissertation is a cross-cultural examination of the creation and the socio- cultural implications of the languages of pain in the works of French author, Marguerite Duras and Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo. Recent studies have determined that discursive communication is insufficient in expressing one’s pain. In particular, Elaine Scarry maintains that pain destroys language and that its victims must rely on the vocabulary of other cultural spheres in order to express their pain. The problem is that neither Scarry nor any other Western pain scholar can provide an alternative to discursive language to express pain. This study claims that both artists must work beyond their own cultural registers in order to give their pain a language. In the process of expressing their suffering, Duras and Kahlo subvert traditional literary and artistic conventions. Through challenging literary and artistic forms, they begin to re-think and ultimately re-define the way their readers and viewers understand feminine subjectivity, colonial and wartime occupation, personal tragedy, the female body, Christianity and Western hegemony. -

No. 260 Romane Fostier. Marguerite Duras. Paris

H-France Review Volume 19 (2019) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 19 (December 2019), No. 260 Romane Fostier. Marguerite Duras. Paris : Gallimard, collection Folio biographies (n° 146), 2018. 304 pages + dossier photographique de 8 pages. Repères chronologiques et références bibliographiques (œuvres de Marguerite Duras et biographies). 9,40€. ISBN : 9782072694073. Compte-rendu par Catherine Rodgers, Swansea University. De nombreuses biographies de Marguerite Duras ont été publiées, de la très critiquée Duras ou le poids d’une plume rédigée par Frédérique Dubelley, à la très sérieuse C’était Marguerite Duras de Jean Vallier, en passant par la très médiatisée Marguerite Duras de Laure Adler et les nombreux récits plus ou moins romancés d’Alain Vircondelet.[1] Celle de Jean Vallier fait deux volumes de 1669 pages et regorge de preuves et références, témoin de l’énorme travail de recherche entrepris. À de nombreuses reprises, l’auteur réfute les affirmations de Laure Adler et les conclusions un peu hâtives qu’elle tire par endroits. Il faut dire aussi que la qualité des résumés qu’Adler avait rédigés des œuvres de Duras s’amenuisait au cours du volume. La biographie de Jean Vallier est une excellente source d’informations pour les spécialistes de Duras, mais elle peut paraître rebutante pour le non-spécialiste car elle est longue et touffue. Il y avait donc un créneau à combler sur le marché pour une bonne biographie de Duras qui soit d’un accès facile et agréable à lire pour le grand public. Cela a sans doute été le raisonnement des éditions Gallimard pour la publication de ce volume dans la collection Folio biographie. -

En Attendant Robert L. / La Douleur D'emmanuel Finkiel

Document generated on 09/28/2021 5:46 a.m. Ciné-Bulles En attendant Robert L. La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel Nicolas Gendron Dossier 50 ans depuis 1968 Volume 36, Number 3, Summer 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/88635ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Gendron, N. (2018). Review of [En attendant Robert L. / La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel]. Ciné-Bulles, 36(3), 8–11. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Du livre au lm La Douleur d’Emmanuel Finkiel En attendant Robert L. NICOLAS GENDRON Par insatisfaction chronique ou exigence extrême, terand! —, elle échappe de peu à un guet-apens, ou quelque chose entre les deux, l’écrivaine alors que Robert est fait prisonnier politique et en- Marguerite Duras a presque toujours boudé les voyé au camp de Buchenwald. En reviendra-t-il? La adaptations de ses textes — romans ou scéna- Douleur témoigne de l’attente de Marguerite, rios — produites au cinéma, si l’on exclut la réussite jusqu’à la déraison. -

Introduction Bakhtin, "Discourse in the Novel," P. 355. 3. Yaeger, "A Fire In

Notes Introduction 1. Bakhtin, "Discourse in the Novel," p. 355. 2. Ibid., p. 360. 3. Yaeger, "A Fire in my Head," p. 959. 4. Bakhtin,op. cit., p. 271. 5. Ibid., p. 270. 6. Ibid., p. 263. 7. The term "dialogism" is explained by Bakhtin's translators in the text's glossary: "Dialogism is the characteristic epistemological mode of a world dominated by heterglossia. Everything means, is understood, as a part of a greater whole - there is constant interaction between meanings, all of which have the potential of conditioning others. [... [ This dialogic imperative, mandated by the pre-existence of the language world relative to any of its current inhabitants, insures that there can be no actual monologue. One may [... ] be deluded into thinking there is one language, or one may, as grammarians, certain political figures and normative framers of 'literary languages' do, seek in a sophisticated way to achieve a unitary language. In both cases the unitariness is relative to the overpowering force of heteroglossia, and thus dialogism." Ibid., p.426. 8. Ibid., p. 300. 9. Houdebine, "Les Femmes dans la langue," pp. 11-12. All translations from the French in this book are mine unless otherwise indicated. 10. Beauvoir, Le DeuxiCmc sexc. 11. Cixous, "Le Sexe ou la tete," p. 7. 12. Cixous, La Jeune nee, pp. 115-117. 13. Benjamin, "The Bonds of Love," pp. 46-47. 14. Foucault, L'Arc1uzeologic du savoir, p. 90. 15. The term is ambiguous because the French "feminin" signifies both "female" and "feminine." 16. Rosalind-Jones, "Writing the Body," p. 374. 17. -

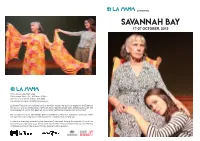

Savannah Bay 17-27 OCTOBER, 2019

presents savannah bay 17-27 OCTOBER, 2019 Office Phone: (03) 9347 6948 Office Hours: Mon – Fri | 10:30am – 5:30pm 349 Drummond Street, Carlton VIC 3053 www.lamama.com.au | [email protected] La Mama Theatre is on traditional land of the Kulin Nation. We give our respect to the Elders of this country and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people past, present and future. We acknowledge all events take place on stolen lands and that sovereignty was never ceded. We are grateful to all our philanthropic partners and donors, advocates, volunteers, audiences, artists and our entire community as we work towards the La Mama rebuild. Thank you! La Mama is financially assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council – its arts funding and advisory body, the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria, and the City of Melbourne through the Arts and Culture triennial funding program. MARGUERITE DURAS BRENDA PALMER savannah bay (Writer) (Madeleine) Written by Marguerite Duras Born in French Indochina, Marguerite Duras (1914- Brenda likes nothing better than trying to fathom under Directed by Laurence Strangio 1996) was one of the most significant 20th century Laurence’s direction the sometimes unfathomable literary figures in France. The author of many novels, Marguerite Duras – firstly L’Amante Anglaise, then Performed by Brenda Palmer and Annie Thorold plays, essays and screenplays, she is best known The Atlantic Man and The Lover (with Annie Thorold, Set design by Laurence Strangio outside France for her filmscript Hiroshima, mon twice!) and now Savannah Bay – and at her theatre (within the set design by Bronwyn Pringle for The Disappearing Trilogy) Amour (filmed by Alain Resnais in 1959) and her best- of choice, La Mama. -

The University of Chicago Notes Taking Sides: Social

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO NOTES TAKING SIDES: SOCIAL AND AESTHETIC MEANINGS OF MUSIC IN THE NOVEL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES BY VEERLE DIERICKX CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2020 COPYRIGHT 2020 VEERLE DIERICKX For August TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 . MUSIC AND LITERATURE ........................................................................................................ I . WAGNERISM ........................................................................................................................... J . MUSIC AND THE NOVEL ......................................................................................................... L . APPROACH ............................................................................................................................ HJ . CHAPTER OUTLINE ................................................................................................................ HN CHAPTER II: THE FIGURE OF THE COMPOSER .................................................................. 27 . -

Une Étude De L'œuvre Moderato Cantabile De Marguerite Duras

Intimisme et psychocritique: une étude de l’œuvre Moderato Cantabile de Marguerite Duras Júlia Ferreira Université Fédérale du Acre - UFAC Synergies Brésil Résumé : Marguerite Duras est un écrivain que nous désignerons d’intimiste. 125-131 n° spécial 1 - 2010 pp. Elle est intimiste lorsque son écriture met en scène vie et œuvre. Dans ces deux mondes, l’intime ne se traduit que par les silences et le secret. L’intime s’exprime, quand l’auteur traduit l’intraduisible: une histoire personnelle qui demeure dans son état latent. Ainsi, entre continuité et discontinuité du discours, l’intime trouve finalement son origine autours du manque et de l’absence. Pour les décrire, l’auteur met en lumière la musique. Elle symbolise le présent et le passé, la mémoire et l’oubli, l’amour et la mort, thèmes durassiens par excellence. Sans relier vie e œuvre, on constate que tous ces fantasmes de l’écriture sont directement liés à l’enfance de l’auteur. Ils sont précisément liés à la mort de son jeune frère. Cette histoire intime l’a marquée profondément, jusqu’à la mort de l’auteur. Mots-clés: mémoire, oubli, amour et mort Resumo: Marguerite Duras é uma escritora que designamos de intimista. Ela é intimista quando sua escritura coloca em cena vida e obra. Nestes dois mundos, o íntimo se traduz por silêncio e por segredo. O íntimo se revela quando a autora traduz o não traduzível: uma história pessoal que reside no estado latente. Assim, entre continuidade e descontinuidade do discurso, o íntimo se encontra finalmente sua origem em torno da falta e da ausência. -

H-France Review Vol. 19 (November 2019), No. 252 Mary Noonan And

H-France Review Volume 19 (2019) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 19 (November 2019), No. 252 Mary Noonan and Joëlle Pagès-Pindon, Marguerite Duras: Un théâtre de voix / A Theatre of Voices. Leiden and Boston: Brill-Rodopi, 2018. xviii + 224 pp. Index. $252.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-90-04-36096-9; $119.00 U.S. (eb). ISBN 978-90-04-36874-3. Review by Anne Brancky, Vassar College. Marguerite Duras: Un théâtre de voix / A Theatre of Voices is a wonderful, bilingual (French and English) new book that offers useful and innovative additions to scholarship on Marguerite Duras’s extensive work for and with the theater. Though perhaps better known as a novelist and screenwriter, Duras wrote dozens of plays throughout her long career and had a very idiosyncratic, experimental, and avant-garde approach to writing for the stage. As Joëlle Pagès- Pindon and Mary Noonan point out, Duras herself even mounted several of her plays (Le Shaga and Yes, peut-être in 1968, La Musica and Les Eaux et forêts in 1976, Savannah Bay in 1983, and La Musica Deuxième in 1985), attesting to her commitment to the performative mode and to her genre-bending style. This interdisciplinary collection, edited by two very accomplished leaders in the field of Duras studies, marshals the skills and expertise of groundbreaking scholars and practitioners in theater and performance studies to analyze the many contributions of Duras and her theater. As the editors argue in the concise preface to this volume, Duras’s plays have been underestimated in regards to her own vast oeuvre but also in regards to twentieth-century French theater more broadly. -

Fictionalising Trauma. the Aesthetics of Marguerite Duras´S India Cycle

Sirkka Knuuttila Fictionalising Trauma The Aesthetics of Marguerite Duras’s India Cycle Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 12th of December, 2009 at 10 a’clock. ISBN 978-952-92-6405-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-5858-5 (PDF) Helsinki University Print Helsinki 2009 Il fallait receler un pouvoir secret pour avoir cette force, dans la vie. Marguerite Duras Table of Contents Acknowledgements Abbreviations Introduction ..................................................................... 1 Reading Colonial Trauma: A Cognitive Approach ........................ 7 On Duras’s Cyclic Aesthetics .......................................... 14 Narrativising Trauma: The Duality of Traumatic Memory. 21 The Outline of the Study .............................................. 28 I. Memory, Discourse, Fiction: The Birth of the Absent Story......... 30 On Duras’s Critical Working-Through ........................................ 34 Between Melancholy and Mourning: L’affection intentionnelle ................. 41 Dismantling Literality ........................................................ 46 II. The Aesthetic Strategies of the India Cycle ........................ 51 Repetition: Paralleling Analogous Structures ................................. 55 Homologies, Doublings, Reversals ........................................ 59 Romantic Formula: Contamination and Multiplication ................... 64 Metafiction and Testimony: Possible Worlds ................................