University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OUTSTANDING WARRANTS As of 10/10/2017

OUTSTANDING WARRANTS as of 10/10/2017 AGUILAR, CESAR JESUS ALEXANDER, SARAH KATHEREN ALLEN, RYAN MICHAEL A AGUILAR, ROBERTO CARLOS ALEXANDER, SHARRONA LAFAYE ALLEN, TERRELL MARQUISE AARON, WOODSTON AGUILERA, ROBERTO ALEXANDER, STANLEY TOWAYNE ALLEN, VANESSA YVONNE ABABTAIN, ABDULLAH AGUILIAR, CANDIDO PEREZ ALEXANDER, STEPHEN PAUL ALMAHAMED, HUSSAIN HADI M MOHAMMED A AHMADI, PAULINA GRACE ALEXANDER, TERRELL ALMAHYAWI, HAMED ABDELTIF, ALY BEN AIKENS, JAMAL RAHEEM ALFONSO, MIGUEL RODRIGUEZ ALMASOUDI, MANSOUR ABODERIN, OLUBUSAYO ADESAJI AITKEN, ROBERT ALFORD, LARRY ANTONIO MOHAMMED ALMUTAIRI, ABDULHADI HAZZAA ABRAMS, TWANA AKIBAR, BRIANNA ALFREDS, BRIAN DANIEL ALNUMARI, HESHAM MOHSMMED ABSTON, CALEB JAMES AKINS, ROBERT LEE ALGHAMDI, FAHADAHMED-A ALONZO, RONY LOPEZ ACAMPORA, ADAM CHRISTOPHER AL NAME, TURKI AHMED M ALHARBI, MOHAMMED JAZAA ALOTAIBI, GHAZI MAJWIL ACOSTA, ESPIRIDION GARCIA AL-SAQAF, HUSSEIN M H MOHSEB ALHARBI, MOHAMMED JAZAA ALSAIF, NAIF ABDULAZIZ ACOSTA, JADE NICOLE ALASMARI, AHMAD A MISHAA ALIJABAR, ABDULLAH ALSHEHRI, MAZEN N DAFER ADAMS, ANTONIO QUENTERIUS ALBERDI, TOMMY ALLANTAR, OSCAR CVELLAR ALSHERI, DHAFER SALEM ADAMS, BRIAN KEITH ALBOOSHI, AHMED ABALLA ALLEN, ANDREW TAUONE ALSTON, COREY ROOSEVELT ADAMS, CHRISTOPHER GENE ALBRIGHT, EDMOND JERRELL ALLEN, ANTHONY TEREZ ALSTON, TORIANO ADARRYL ADAMS, CRYSTAL YVONNE ALCANTAR, ALVARO VILCHIS ALLEN, ARTHUR JAMES ALTMAN, MELIS CASSANDRA ADAMS, DANIEL KENNETH ALCANTAR, JOSE LUIS MORALES ALLEN, CHADWICK DONOVAN ALVARADO, CARLOS ADAMS, DARRELL OSTELLE ALCANTARA, JESUS ALLEN, CHRISTOPHER -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Un Manual De Matematicas Y Ciencas Utilizando Inteligencias Multiples

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 727 FL 025 109 TITLE Un Marco Abierto: Un Manual de Matematicas yCiencas Utilizando Inteligencias Multiples Disenado para Estudiantes Bilingues de Educacion General y Especial (An Open Framework: A Math and Science Manual UtilizingMultiple Intelligences Designed for Bilingual Students in General and Special Education). INSTITUTION New York City Board of Education, Brooklyn, NY.Office of Bilingual Education. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 151p. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Instructional Publications Bookstore, Room 608, 131 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) LANGUAGE Spanish EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bilingual Education; Bilingual Students; Cognitive Mapping; Elementary Education; *English (Second Language);Gifted; Grade 4; Grade 5; Grade 6; Grade 7; Grade 8; Instructional Materials; Lesson Plans; *Mathematics Education; *Multiple Intelligences; *Science Education; Second Language Instruction; Semantics; Spanish; Special Education;Teaching Guides; *Thematic Approach ABSTRACT This manual incorporates a Multiple Intelligences perspective into its presentation of themes and lesson ideasfor Spanish-English bilingual elementary school students ingrades 4-8 and is designed for both gifted and special education uses. Eachunit includes practice activities, semantic maps to illustrate and helporganize ideas as well as curricular connections in mathematics and science,and ESL linguistic summaries which provide examples on how to develop ESLactivities for English vocabulary.(CNP) -

ARQUEOLOGIA 1 Bloantropologla Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE

ERES ARQUEOLOGIA 1 BlOANTROPOLOGlA Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE INSTITUTO CANARIO DE BlOANTROPOLOGlA Sumario Otros conceptos. otras miradas nuestra arqueologla. A sobre la religión de los guanches: propósito de los Cinithi o Rafael González Antón et al1 El Zanatas: Rafael González Antón lugar arqueológico de Butihondo et al/ La Antropologia Física y (Fuerteventura): M' del Carmen su aplicación a -la justicia en del Arco Aguilar et al1 España: una perspectiva Prospección arqueológica del histórica: Conrado Rodriguez litoral del sur de la Isla deTenerife: Martin et al1 Problemas Granadilla, San Miguel de Abona conceptuales de las y Arona:Alfredo Mederos Martín entesopatias en Paleopatologla: et al1 Sobre el V Congreso Dornenec Campillo et al/ The Panafricano de Prehistoria (Islas leprosarium of Spinalonga Canarias, 1963): Enrique Gozalbes (1 903- 1957) in eastern Crete Craviotol Relectura sobre (Greece): Chryssi Bourbou ORGANISMO AUlüNOMO DE MUSEOS Y CENTROS . COMITÉEDITORIAL - , . , . .. Dirección . : RAFAEL GONZALEZ ANTÓN arqueología)^' CONRADO RODRÍGUEZ MARTÍN '(Bioantropología) ' 7 , . .. ; . Secretaría ,,., ..;',!'.:.. ' CANDELARIA ROSARIO ADRIÁN: .- , ?, . MERCEDES DELARCO AGUILAR . -."' ' -, ,. , ,. %, %, Consejo Editorial . ., ENRIQUE GOZALBES CRAVIOTO JOSÉ CARLOS CABRERA PEREZ (Univ. Castilla-La Mancha) . (Patrimonio Histórico. Cabildo de Tenerife) . JOAN RAMÓN TORRES' . JOSE J. JIMÉNEZ GONZÁL.EZ . ' (Unidad de Patrimonio.' (Museo Arqueológicode Tenerife. Diputación de Ibiza) .' . O.A.M.C.) ' Consejo Asesor ARTHUR C. AUFDERHEIDE' FERNANDO ESTÉVEZ. GONZÁLEZ: (Univ. de Minnesota) ,. .! ' . '. (Univ. de La Lagunaj ' ' . , : . - . ., . , RODRIGO DE BALBÍN BEH~ANN : PRIMITIVA BUENO RAM~REZ : ' (Univ. de Aicalá de ~enaks) - . .. (Univ. de Alcalá de'Henares) ... , . , .. ANTONIO;SANTANA SAF~TANA ' ..PABLO ATOCHE PEÑA (Univ. de Las Pa1mas)j. ' (Univ. de Las Palmas) . , ; ... FRANCISCO-r~~~~í~-~~~~.v~~CASAÑAS . .. (M&eo"de kiencias Nakra'íe~.O.A.M.C.) , . -

Nistspecialpublication260-150.Pdf

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg Campus, 1999 NIST 260-150 Standard Reference Materials - The First Century Stanley D. Rasberry, Author Tomara Arrington, Composition and Design Standard Reference Materials Program Technology Services National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899-2320 June 2002 U.S. Department of Commerce Donald L. Evans, Secretary Technology Administration Phillip Bond, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Arden L. Bement, Jr. Director Please visit our website www.nist.gov/srm Foreword Standard Reference Materials have played a major role in the history of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), as well as its predecessor organization, the National Bureau of Standards (NBS). Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) were one of the first tangible outputs from the nation’s investment in improved measurement standards and technology that was start- ed at the beginning of the 20th century. As NBS evolved over the last hundred years in terms of scientific capability and fields of work, SRMs have taken on new forms and new roles in ensuring that our Nation is second to none in measurement capability. No one is more familiar with the history of this important program than Stanley Rasberry, long- time Chief of the program as well as a major developer of SRMs himself. In this retrospective, Raspberry captures the spirit and importance of the program for analysts, researchers and tech- nologists everywhere. The reader will find this lively exposition both informative and enlighten- ing about of NIST’s most important programs. John Rumble August 2002 Acknowledgment The Author wishes to acknowledge the fine contributions of Nancy Trahey-Bale and Lee Best for their assistance in preparing this document. -

1922-10-10 [P

DESPUES DE TRES MINUTOS NO LB BELLO . QUEDABA VESTIGIO DE EN LA CARA EL TERRIBLE GUILLERMO Te siente preocupado i No es necesario que Ud. reciba trata mientes eléctricos, tampoco que se torta- re al arrancar e. bello de su cara basta con que use este polvo y después de tres es eso, Gailler- \ minutos no le quedar ves.icio de bello Qué Porque el payaso no sé mo? por qué vienes 1 Que yo qué en ia cara, su piel adquirir frescura y se va a aca- florando del Circo? dijo que va a ser de mi si en bellesa. Esta preparación no causa nin bar el mundo y que la o ira encarnación me Kn dao o molestia a las personas de nacer eutits delicado. tendremos que toca nacer mujer:.... Pida Ud. un pomo de este polvo y ha. nuevo. de .™a desaparecer d pelo superfluo de su cara, cuello, brazos y antebrazos .sin ex- perimentar el ms mnimo dolor. Precio $2.00. Mande Ud. soamente 25c, en es- tampillas postales o en efectivo y paga, r el resto cuando le sea entregado el polvo en su domicilio. Escriba a la e- guiente dirección: A. KENDIS 130 E. 4th St. New York N. Y. LAS ESPINILLAS ABA- 7255555555552555555525255555525555555£55^ TEN A LOS JOVENES! UNA COMBINACION BE DEL DIA CUENTO Y También Arruinan a las Seoritas CARTAS DE ESPAA Como, S.S.S. evita positivamente EL BAUTIZO las erupciones cutneas. INTERES A LAS MUJERES §^55555552555525252525555552525525555255255525^ Las espinillas y erupciones de la piel tienen Muchos vestidos con sus riente, de dieciocho aos apenas, dan- hombres, precio,—usted paga por cada barro, fstula o do el a ai de fiesta, ca Ja puer brazo marido. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1995

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1995 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaishah 1 Aillen 21 Alexa 1 Aakanksha 10 Aimee 1 Alexana 1 Aaliyah 1 Aimee-Jeanne 2 Alexander 3 Aaron 1 Aimee-Lynn 156 Alexandra 1 Aashima 1 Aimie 1 Alexandrea 1 Abagail 3Ainsleigh 39 Alexandria 1 Abbagayle 4Ainsley 1 Alexendra 8 Abbey 4 Aisha 9 Alexia 1 Abbie 1 Aislinn 40 Alexis 1 Abbigail 1 Aislynn 1 Alexiss 7 Abby 1 Aiyanna 3 Alexus 1 Abby-Lynne 1 Ajak-Angela 1 Alexx 1 Abeer 1 Ajjia 1 Aleya 1 Abigael 1Akari 1 Aleysha 29 Abigail 1Aki 1 Alham 1 Abigayle 1Akita 2 Ali 1 Abilene 1 Akuuma 7 Alice 1 Abrar 1Ala 32 Alicia 1 Abriana 2 Alaa 1 Aliecia 1 Acacia 2 Alaina 1 Alina 1 Acelyn 1 Alaine 1 Alintina 1 Ada 23 Alana 2 Alisa 1 Adaira 1 Alanah 1 A'Lisa 2 Adara 3 Alandra 25 Alisha 1 Adaya 1 Alanis 1 Alisha-Dale 2 Adele 24 Alanna 3 Alishia 1 Adeline 7 Alannah 19 Alison 1 Adhara 1 Alanna-Marie 10 Alissa 1 Adileena 2Alara 2 Alita 3 Adina 1Alastria 7 Alix 1 Adisa 1 Alayna 3 Aliya 1 Aditi 2 Alberta 2 Aliza 1 Adora 1 Alden 1 Allana 1 Adrea 4 Aleah 3 Allanah 2 Adrian 1 Aleasha 1 Allap 8 Adriana 5Alecia 1 Allayna 1 Adriana-Maria 2 Aleena 1 Alleah 4 Adrianna 3 Aleesha 1 Allesha 1 Adrianne 1 Aleida 1 Allex 10 Adrienne 1 Aleigha 1 Alleycia 1 Aeisha 1 Aleighsha 1 Alli 1 Afton 3 Aleisha 3 Allie 3 Aganetha 1 Alejandrina 3 Allisha 1 Agatha 1 Aleksandra 41 Allison 2 Agnes 5 Alena 1 Allyesha 1 Ahlam 4 Alesha 1 Allynna 1 Aida 3 Alessandra 1 Allysa 3 Aidan 2 Alessia 2 Allysha 1 Ailcey 1 Alethea 1 Allysia 4 Aileen 4Alex 7 Allyson Baby Girl Names Registered in 1995 Page 2 of -

Erken Lydia Dönemi Tarihi Ve Arkeolojisi

T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ARKEOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI 2019-YL–196 ERKEN LYDIA DÖNEMİ TARİHİ VE ARKEOLOJİSİ HAZIRLAYAN Murat AKTAŞ TEZ DANIŞMANI Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ AYDIN- 2019 T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE AYDIN Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Programı öğrencisi Murat AKTAŞ tarafından hazırlanan Erken Lydia Dönemi Tarihi ve Arkeolojisi başlıklı tez, …….2019 tarihinde yapılan savunma sonucunda aşağıda isimleri bulunan jüri üyelerince kabul edilmiştir. Unvanı, Adı ve Soyadı : Kurumu : İmzası : Başkan : Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ ADÜ ………… Üye : Doç. Dr. Ali OZAN PAÜ ………… Üye : Dr. Öğr. Üyesi. Aydın ERÖN ADÜ ………… Jüri üyeleri tarafından kabul edilen bu Yüksek Lisans tezi, Enstitü Yönetim Kurulunun …………..tarih………..sayılı kararı ile onaylanmıştır. Doç. Dr. Ahmet Can BAKKALCI Enstitü Müdürü V. iii T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE AYDIN Bu tezde sunulan tüm bilgi ve sonuçların, bilimsel yöntemlerle yürütülen gerçek deney ve gözlemler çerçevesinde tarafımdan elde edildiğini, çalışmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düşünce, sonuç ve bilgilere bilimsel etik kurallarının gereği olarak eksiksiz şekilde uygun atıf yaptığımı ve kaynak göstererek belirttiğimi beyan ederim. …../…../2019 Murat AKTAŞ iv ÖZET ERKEN LYDIA DÖNEMİ TARİHİ VE ARKEOLOJİSİ Murat AKTAŞ Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ 2019, XVI + 157 sayfa Batı Anadolu’da Hermos (Gediz) ve Kaystros (Küçük Menderes) ırmaklarının vadilerini kapsayan coğrafyaya yerleşen Lydialılar'ın nereden ve ne zaman geldikleri kesin olarak bilinmemektedir. Ancak Lydialılar'ın MÖ II. bin yılın ikinci yarısından itibaren Anadolu’da var oldukları anlaşılmaktadır. Herodotos, Troia savaşından itibaren Herakles oğullarının bölgede beş yüz yıl hüküm sürdüğünden bahseder. -

An Ethnographic Study on Hispanic Mothers in Family Drug Court

BREAKING THE CYCLE: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON HISPANIC MOTHERS PARTICIPATING IN FAMILY DRUG COURT by Rhonda Sue Tyler Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2018 2 BREAKING THE CYCLE: AN ETHNOGRAPIC STUDY ON HISPANIC MOTHERS PARTICIPATING IN FAMILY DRUG COURT by Rhonda Sue Tyler A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2018 APPROVED BY: Tamika Hibbert, Ed.D., LPC, NCC, Committee Chair Travis Bradshaw, Ph.D., Committee Member Amy McLemore, Ed.D., Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT The purpose of this critical ethnographic study was to understand the phenomena of generational substance abuse of Hispanic mothers. By participating in family drug court (FDC), a therapeutic judicial program, rather than incarceration, mothers have a greater opportunity to address their substance abuse issues (Brown, 2010). Motivated to restore their domestic structures, FDC often allows them to address their substance abuse issues and regain custody of their children, who are usually in family or state’s care (Choi, 2012). In this study, generational substance abuse will be generally defined as those women who are FDC participants and have lost custody of their children, predisposing their children to become substance abusers. The theories guiding this study are Vygotsky’s (1934) Social Development Theory due to his work with the interdependence of individual and social processes; Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (1986) on human motivation and action; and the cultural work of Boas and Mead (1928). A FDC counselor, (gatekeeper of this study), provides access to clients in FDC and to graduates for up to one year. -

Antologãła De La Clase

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Student Scholarship 8-2018 Antología de la clase Britton W. Newman Wofford College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Britton W., "Antología de la clase" (2018). Student Scholarship. 21. https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs/21 This Class Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Antología de la clase Creative Writing in Spanish Spanish 441 Clase del prof. Britt Newman 2018 Índice Ensayos Orlando Barrientos “El primer día” 3 Mariana Carreño “Cambio de escena” 7 Lydia Estes “La oficina 2.0” 12 “Y voy a llamarla Layla” 14 Erica Fulton “Casados de Costa Rica” 20 Mary Burgess Harrelson “La vida corta” 25 Bijonae Jones “Palabras alemanas” 30 Brooke Leftwich “Una cosa del sur” 34 Crystal Rivers “¿Dónde estoy? 39 Sarah Spiro “Una historia escuchada” 43 “Una parroquiana” 47 Eric Stanley “Viaje solo a Nueva York” 49 “Un sabor americano en una casa española” 53 Holly Stevens “Encontrar mi lugar con una cebolla” 55 Relatos Phyllicia Colvin-Panton “Capítulos” 60 Helen Cribb “Auténtico” 66 Lydia Estes “Llena la botella” 71 Emma Hauser “Una historia incalculable” 77 Sarah Spiro “Hoy aquí, mañana ya no” 82 2 Ensayos 3 “El primer día” Orlando Barrientos Eran las seis de la mañana y estaba afuera sosteniendo la mano de mi madre. -

Gümüşhane Üniversitesi

GÜMÜŞHANE ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ELEKTRONİK DERGİSİ ISSN: 1309-7423 GÜMÜŞHANE UNIVERSITY ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF THE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SÜRDÜRÜLEB İLİR TUR İZM KONGRES İ ÖZEL SAYISI The Special Issue of Sustainable Tourism Congress Cilt/Volume:CİLT: 1 SAYI: 6 Sayı/Number: 1 14 Yıl/Year: YIL: 20152010 GÜMÜ ŞHANE ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ ELEKTRONİK DERGİSİ Cilt: 6 Sayı 14 Aralık 2015 SÜRDÜRÜLEB İLİR TUR İZM KONGRES İ ÖZEL SAYISI Sahibi Prof. Dr. İhsan GÜNAYDIN Gümü şhane Üniversitesi Rektörü Editörler Yrd. Doç. Dr. Salih YILDIZ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Abdurrahman ALTUNTA Ş Dergi Sekreteryası Ar ş. Gör. Şerife DEM İRELL İ Öğr. Gör. Özlem SEKMEN İleti şim Adresi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Elektronik Dergisi Sekreteryası Gümü şhane Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Ba ğlarba şı 29100 / GÜMÜ ŞHANE Tel: 0456 233 7425 Dahili: 2203 Fax: 0456 233 7553 [email protected] http://sbedergi.gumushane.edu.tr/ ISSN 1309-7423 GUSBEED , ve Tarafından Taranmaktadır. Gümü şhane Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Elektronik Dergisi Sayı 14 Aralık 2015 HAKEM İNDEKS İ / REFEREE INDEX Dr. A. Celil Çakıcı Dr. Aşkın Keser Mersin Üniversitesi Uluda ğ Üniversitesi Dr. A. Mesud Küçükkalay Dr. Aybuke Ceyhun Sezgin Eski şehir Osman Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi Üniversitesi Dr. Abdullah Ergin Dr. Aydın Çevirgen Gazi Üniversitesi Akdeniz Üniversitesi Dr. Abdülkadir Bulu ş Dr. Azize Hassan Selçuk Üniversitesi Gazi Üniversitesi Dr. Abdülsamet Yaman Dr. Azzem Özkan Ardahan Üniversitesi Erciyes Üniversitesi Dr. Adem Çaylak Dr. Bahattin Özdemir Yıldırım Beyazıd Üniversitesi Akdeniz Üniversitesi Dr. Ahmet Hamdi Aydın Dr. Bayram Nazır Kahramanmara ş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Gümü şhane Üniversitesi Dr. Ahmet Hamdi Topal Dr. -

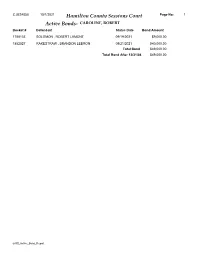

Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount

CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 1 Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1788133 SOLOMON , ROBERT LAMONT 09/19/2021 $9,000.00 1852527 RAKESTRAW , BRANDON LEBRON 09/21/2021 $40,000.00 Total Bond $49,000.00 Total Bond After 12/31/04 $49,000.00 arGS_Active_Bond_Report CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 2 Active Bonds- A BONDING COMPANY Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1768727 LEE , KAITLIN M 06/30/2019 $12,500.00 1792502 WAY , JASON J 01/11/2020 $3,000.00 1796727 FERRY , MATTHEW BRIAN 02/21/2020 $2,500.00 1804712 VILLANUEVA , ADAM LOUIS 05/25/2020 $3,000.00 1809034 SINFUEGO , NARCIAN LYNET 07/12/2020 $2,000.00 1817402 PETER , DALE NEIL 08/14/2021 $0.00 1830111 HAZLETON , SAMUEL T 02/14/2021 $2,000.00 1830122 HILL , JARED LEVI 02/14/2021 $500.00 1831701 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $5,000.00 1831702 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $2,000.00 1835471 SHROPSHIRE , EDWARD LEBRON 04/06/2021 $1,500.00 1839064 CHESNUTT , ALAN ARNOLD 05/06/2021 $2,500.00 1839968 SAARINEN , NICHOLAS AARRE 05/15/2021 $1,500.00 1844159 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $3,000.00 1844160 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $2,000.00 1844161 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1844162 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1846317 SMALL II, AARON CLAY 07/20/2021 $2,000.00 1846876 GIARDINA , MICHAEL N 07/24/2021 $3,000.00 1847003 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,500.00 1847004 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,000.00 1847006 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $500.00 1847417