Bus Rapid Transit Corridors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority Joe Calabrese - General Manager RTA Ridership by Mode ! 500 Buses - 75 % ! 60 Heavy Rail Vehicles - 10% ! 24 RTV’s (BRT) - 8% ! 48 Light Rail Vehicles - 6% ! Paratransit - 100 vehicles - 1% RTA Fleet GCRTA HealthLine Euclid Avenue Transformation Euclid Avenue History Euclid Avenue History Alternatives Analysis - late 1990’s ! Subway ! Light Rail ! Do Nothing (keep the #6 bus) ! Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Mode Selection Criteria ! Capacity (30,000 + daily customers) ! Connectivity ! Funding possibilities (FTA) ! Cost - capital and operating ! Economic development potential " Renew Aging Infrastructure Vision for the “Silver Line” BRT ! “Rail Like” Image ! Fast ! Simple ! Safe ! First Class ! Help Revitalize Corridor Euclid Corridor Project ! 9.38 miles long ! 36 stations (from 100 bus stops) ! Travel time from 40 to 28 minutes ! Building face to building face ! Pedestrian and bicycle friendly ! Landscape/hardscape treatment ! Pubic Art - Integrated/stand-alone Exclusive Right of Way Funding Pie Charts FTA 80% ODOT 20% 2000 ODOT FTA 25% 50% City MPO RTA 2004 Ground Breaking October 2004 “Silver Line” Construction “Silver Line” Construction (3.5 years) “Silver Line” Construction “Silver Line” Construction “Silver Line” Construction “Rail Like” Image ! Reduced Travel Time " Multi-Door Boarding " Exclusive Right-of-Way " Traffic Signal Prioritization " Higher Travel Speeds " Level Boarding " Precision Docking " Rear Facing Wheel Chair Restraints " Off-Board Fare Collection “Rail Like” Image ! Hi-Frequency -

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority Joe Calabrese – General Manager Greater Cleveland RTA Overview . Service Area 59 municipalities 500 square miles Population of 1.5 million . Customers Served 200,000 on a typical weekday 1 RTA Overview . Services Modes 500 Buses 100 Paratransit Vans 20 Job Access Vans 60 Heavy Rail Vehicles 48 Light Rail Vehicles 24 RTV’s - (HealthLine BRT) 2 RTA Fleet 3 GCRTA HealthLine Euclid Avenue Transformation Euclid Avenue History 4 Euclid Avenue History Euclid Avenue History . Streetcars disappeared in 1954 . # 6 Bus Route put in service Great Service with Low Image . Alternative Analysis Subway or Light Rail Do Nothing (keep the #6 bus) Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) 5 Mode Selection Criteria . Capacity (30,000 + daily customers) . Connectivity . Funding possibilities (FTA) . Cost Capital Operating . Economic development potential Vision for the “Silver Line” . “Rail-Like” Image . Fast . Simple . Safe . First Class . Promote Economic Development 6 Euclid Corridor Project – 9.38 Miles . 36 stations . Travel time from 28 to 40 minutes . Building face to building face . Pedestrian friendly with bike lanes . Landscape/hardscape treatment 1,500 trees with irrigation . Integrated/stand-alone public art 7 Ground Breaking October 2004 8 Funding Pie Charts - $200 Million FTA 80% ODOT 20% 2000 ODOT FTA 25% 50% City MPO RTA 2004 Exclusive Right of Way 9 10 11 “Rail-Like” Characteristics . Quicker Travel Times Exclusive Right-of-Way Higher Travel Speed Limit Traffic Signal Prioritization Precision Docking Level Boarding “Stations” Off Board Fare Collection 12 “Rail-Like” Service and Image . Hi-Frequency Service 24x7 Peak every 5 minutes Off-Peak every 8 to 15 minutes . -

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Light Rail Transit

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and Light Rail Transit (LRT) Performance Characteristics Stations Mixed Traffic Lanes* Service Characteristics Newest Corridor End‐to‐End Travel Departures Every 'X' Travel Speed (MPH) City Corridor Segment Open length (mi) # Spacing (mi) Miles % Time Minutes BRT Systems Boston Silver Line Washington Street ‐ SL5 2002 2.40 13 0.18 1.03 42.93% 19 7 7.58 Oakland San Pablo Rapid ‐ 72R 2003 14.79 52 0.28 14.79 100.00% 60 12 14.79 Albuquerque The Red Line (766) 2004 11.00 17 0.65 10.32 93.79% 44 18 15.00 Kansas City Main Street ‐ MAX "Orange Line" 2005 8.95 22 0.41 4.29 47.92% 40 10 13.42 Eugene Green Line 2007 3.98 10 0.40 1.59 40.00% 29 10 8.23 New York Bx12 SBS (Fordham Road ‐ Pelham Pkwy) 2008 9.00 18 0.50 5.20 57.73% 52 3 10.38 Cleveland HealthLine 2008 6.80 39 0.17 2.33 34.19% 38 8 10.74 Snohomish County Swift BRT ‐ Blue Line 2009 16.72 31 0.54 6.77 40.52% 43 12 23.33 Eugene Gateway Line 2011 7.76 14 0.55 2.59 33.33% 29 10 16.05 Kansas City Troost Avenue ‐ "Green Line" 2011 12.93 22 0.59 12.93 100.00% 50 10 15.51 New York M34 SBS (34th Street) 2011 2.00 13 0.15 2.00 100.00% 23 9 5.22 Stockton Route #44 ‐ Airport Corridor 2011 5.50 8 0.69 5.50 100.00% 23 20 14.35 Stockton Route #43 ‐ Hammer Corridor 2012 5.30 14 0.38 5.30 100.00% 28 12 11.35 Alexandria ‐ Arlington Metroway 2014 6.80 15 0.45 6.12 89.95% 24 12 17.00 Fort Collins Mason Corridor 2014 4.97 12 0.41 1.99 40.00% 24 10 12.43 San Bernardino sbX ‐ "Green Line" 2014 15.70 16 0.98 9.86 62.79% 56 10 16.82 Minneapolis A Line 2016 9.90 20 0.50 9.90 100.00% 28 10 21.21 Minneapolis Red Line 2013 13.00 5 2.60 2.00 15.38% 55 15 14.18 Chapel Hill N‐S Corridor Proposed 8.20 16 0.51 1.34 16.34% 30 7.5 16.40 LRT Systems St. -

Indygo Red Line Rapid Transit Indianapolis, Indiana Small Starts Project Development (Rating Assigned November 2016)

IndyGo Red Line Rapid Transit Indianapolis, Indiana Small Starts Project Development (Rating Assigned November 2016) Summary Description Proposed Project: Bus Rapid Transit 13.1 Miles, 28 Stations Total Capital Cost ($YOE): $96.33 Million Section 5309 Small Starts Share ($YOE): $74.99 Million (77.8%) Annual Operating Cost (opening year 2018): $7.03 Million Existing Corridor Ridership (Warranted): 7,800 Daily Linked Trips Overall Project Rating: Medium Project Justification Rating: Medium Local Financial Commitment Rating: Medium Project Description: The Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation (IndyGo) proposes to build a bus rapid transit (BRT) line connecting the Indianapolis central business district (CBD) with the Village of Broad Ripple to the north, and the University of Indianapolis campus to the south. The project includes approximately 7.7 miles of dedicated bus lanes, traffic signal priority at intersections, and stations with weather protection, level vehicle boarding, real-time bus arrival information, and self-service fare vending. The project includes the purchase of 12 60- foot electric battery-powered buses. Service would be provided 20 hours per weekday, with buses every ten minutes during daytime hours and every 30 minutes during the evening. Weekend service would be provided 18 hours per day, with buses every 15 minutes during service hours. Project Purpose: The project will provide fast, reliable, convenient transit service in a key corridor serving downtown Indianapolis. It will operate through the densest area of the city, which has among the most diverse land uses in the region. The route serves four major universities, several hospitals, government agency offices, other community services, and the new Downtown Transit Center, which offers transfer opportunities to numerous connecting bus routes. -

Final Design Traffic Operations Report

FINAL DESIGN TRAFFIC OPERATIONS REPORT IndyGo Red Line Rapid Transit Project – Phase 1 IndyGo April, 2016 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Project Description ........................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................................................... 1-5 1.2.1 Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 1-5 1.2.2 Roadway Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Build Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 1-8 1.3.1 Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 1-8 1.3.2 Roadway Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 1-8 Section 2 Traffic Analysis Methodology ....................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Traffic Impact Thresholds ............................................................................................................................. -

Nvtc Timeline Final

1964 • Urban Mass Transit Act of 1964 paves the way for transit expansion nationwide • Transportation District Act of 1964 creates • NVTC September 1: Initial Commission meeting • NVTC starts work on rapid transit system 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 • Endorse proposed rail rapid transit line • WMATA compact approved • WMATA ocially created • Metro planning begins! • Resolution to start • Outer Beltway Location Committee established • First WMATA board members selected • Right-of-Way preserved Metrorail construction • Washington and Old Dominion Railway for future Metrorail contacted for possible commuter rail line 1973 1972 1971 1970 • NVTC sets transit fares, routes and service levels in NoVA • 3 new bus routes and 20 new buses for the Shirley • Metro groundbreaking, • Grant to build nation’s rst transit way: 1974 • NVTC starts Computeride--a computerized carpool program Highway Bus project Shirley Expressway Shirley Highway Bus project • WMATA builds rst bus shelter – From 1974 to 1986 WMATA builds 828 bus shelters in the region • “Citizens First in Transportation" policy creates the Regional • First “fringe” parking lots – later “Park & Ride • Rosslyn pedestrian • NVTC coordinates Metro station site • NVTC's transfers Computeride to COG to merge with their growing carpool program Citizens Advisory Committee lots” - at the future Springeld Metrorail station bridge opens location and architectural design • NVTC coordinates Fairfax County's new bus program establishing a $100,000 fund to grant to • NVTC supports providing 3 computers for Fairfax, Arlington and site (400 spaces) and Huntington Metrorail • Aerial tour of NoVA with legislators to “any legitimate agency” to provide bus service – service later becomes Fairfax Connector Alexandria for trac signalization station site (150 spaces). -

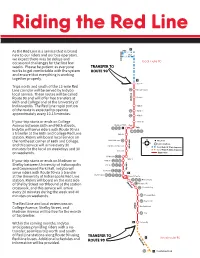

Riding the Red Line

Riding the Red Line A As the Red Line is a service that is brand MERIDIAN 96th new to our riders and our bus operators, 91st we expect there may be delays and local route 90 occasional challenges for the first few weeks. Please be patient as everyone TRANSFER TO works to get comfortable with the system ROUTE 90 and ensure that everything is working together properly. B 66th St. Trips north and south of the 13-mile Red 18 Broad Ripple Line corridor will be served by IndyGo COLLEGE local service. These routes will be called Route 90 and will offer free transfers at Kessler 66th and College and at the University of Indianapolis. The Red Line rapid portion 54th St. of the route is expected to operate 19 52nd St. approximately every 10-15 minutes. 19 46th St. If your trip starts or ends on College 42nd St. Avenue between 66th and 96th streets, Meridian/38th Park 38 28 18 C 38th IndyGo will serve riders with Route 90 via 4 19 38 39 a transfer at the 66th and College Red Line 34th St. station. Riders will board local service on MERIDIAN the northeast corner of 66th and College, 30th/Museum 30 Time Point Connecting Route Fall Creek/Ivy Tech and this service will arrive every 30 Local Route 90: 30 min. frequency Local Route 90: 20 min. frequency minutes for the local on weekdays and 30 22nd St. on weekends. Rapid Transit IU Health 18 28 18th St. 14th St. 18 25 28 If your trip starts or ends on Madison or CAPITOL Shelby between University of Indianapolis 9th St. -

On to 2050 Regionally Significant Projects Benefits Report

ON TO 2050 REGIONALLY SIGNIFICANT PROJECTS BENEFITS REPORT Draft for public comment Draft ON TO 2050 Regionally Significant Projects Benefits Report June 2018 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definition change from previous plans .............................................................................................. 4 Solicitation of projects............................................................................................................................ 5 Evaluation framework ......................................................................................................................... 14 Project evaluation ..................................................................................................................................... 14 Project cost estimates ........................................................................................................................... 14 Capital costs ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Operating costs ................................................................................................................................. 15 Cost summary for projects ............................................................................................................. -

E Line (Expo) Effective 11/02/19

Saturday, Sunday and Holidays Saturday, Sunday and Holidays Effective Nov 2 2019 E Line (Expo) E Line (Expo) Eastbound to Los Angeles (Approximate Times) Westbound to Santa Monica (Approximate Times) SANTA SANTA MONICA WEST ANGELES LOS CENTURY CITY CITY CULVER WEST ADAMS JEFFERSON PARK EXPOSITION PARK DOWNTOWN ANGELES LOS DOWNTOWN ANGELES LOS EXPOSITION PARK JEFFERSON PARK WEST ADAMS CITY CULVER CENTURY CITY WEST ANGELES LOS SANTA MONICA Downtown Santa Monica 17th St/SMC 26th St/ Bergamot Expo/Bundy Expo/Sepulveda Westwood/ Park Rancho Palms City Culver La Cienega/ Jefferson Expo/La Brea Farmdale Expo/Crenshaw Expo/Western Expo/Vermont Expo Park/USC Jefferson/USC LATTC/ Ortho Inst. Pico 7th Street/ Center Metro 7th Street/ Center Metro Pico LATTC/ Ortho Inst. Jefferson/USC Expo Park/USC Expo/Vermont Expo/Western Expo/Crenshaw Farmdale Expo/La Brea La Cienega/ Jefferson City Culver Palms Westwood/ Park Rancho Expo/Sepulveda Expo/Bundy 26th St/ Bergamot 17th St/SMC Downtown Santa Monica — — — 3:27A 3:29A 3:31A 3:35A 3:37A 3:39A 3:42A 3:44A 3:46A 3:50A 3:53A 3:54A 3:56A 3:58A 4:03A 4:05A 4:01A 4:04A 4:08A 4:10A 4:12A 4:14A 4:17A 4:21A 4:23A 4:25A 4:28A 4:30A 4:32A 4:36A 4:38A 4:40A 4:44A 4:46A 4:48A — — — 3:45 3:47 3:49 3:53 3:55 3:57 4:00 4:02 4:04 4:08 4:11 4:12 4:14 4:16 4:21 4:23 4:13 4:16 4:20 4:22 4:24 4:26 4:29 4:33 4:35 4:37 4:40 4:42 4:44 4:48 4:50 4:52 4:56 4:58 5:00 — — — 4:05 4:07 4:09 4:13 4:15 4:17 4:20 4:22 4:24 4:28 4:31 4:32 4:34 4:36 4:41 4:43 4:33 4:36 4:40 4:42 4:44 4:46 4:49 4:53 4:55 4:57 5:00 5:02 5:04 5:08 5:10 5:12 -

Bus Rapid Transit Metroplanning.Org/Brt

FACT SHEET Bus Rapid Transit metroplanning.org/brt What is bus rapid transit and how is it different from a regular bus? Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) provides commuters with a fast, affordable and easy way to travel. Regular buses compete with general traffic on congested roadways. This often causes delays and slow travel speeds. BRT is different as it offers the travel qualities of a rail system on a bus. While regular buses average nine miles per hour, BRT’s limited stops and dedicated lanes with signal priority allow vehicles to travel faster while largely avoiding street congestion. Sleek design and modern technology improve the customer’s experience at a much lower construction cost than rail. The most effective bus rapid transit systems include four critical elements, each of which offers a number of benefits for both transit riders and local communities: Dedicated Lanes Pay-Before-Boarding Stations Transportation: reduced boarding time, faster trips Community: permanence of stations sends positive signal to investors, iconic station design can reinforce community identity Bruce Fingerhood Transportation: faster trips; less traffic congestion; dependable, on-time service Community: more people connected to local destinations, fewer conflicts between modes Lucho Molina Signal Priority Level Boarding Transportation: faster trips, Transportation: reduced reduced bunching, safer travel boarding time, faster trips, more spacious buses Community: improved pedes- trian crossing signals and timing Community: greater acces- sibility to the elderly, people with disabilities, parents with strollers, etc. Aimee Gauthier Rob Wrenn FACT SHEET Bus Rapid Transit metroplanning.org/brt BRT in Chicago MPC’s report Bus Rapid Transit: Chicago’s New Route to Opportunity lays the groundwork for a 10-route BRT network in Chicago that would provide more equitable transit service to help people access jobs, shops, schools, hospitals, and other destinations across the city. -

Attachment 1

1 Abstract This document contains an examination of and recommendations for transit, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure that will help create complete transportation options. With the approval and adoption of this functional plan, the Master Plan of Highways will become the Master Plan of Highways and Transitways. Source of Copies The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 8787 Georgia Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20910 Online at: MontgomeryPlanning.org/transportation/highways/brt 2 Prepared by the Montgomery County Planning Department April 2013 MontgomeryPlanning.org 3 Contents Introduction 8 Planning Context 9 Summary Recommendations 14 Background 17 Vision 20 Why Bus Rapid Transit? 20 Fitting BRT into the County’s Transportation Network 20 Guiding Principles 23 Determining BRT Treatments 24 Dedicated Lanes 24 Median vs. Curb Lanes 25 Lane Repurposing 26 Recommended Corridors and Treatments 28 Recommended Corridors 32 Corridor 1: Georgia Avenue North 33 Corridor 2: Georgia Avenue South 36 Corridor 3: MD 355 North 39 Corridor 4: MD 355 South 42 Corridor 5: New Hampshire Avenue 45 Corridor 6: North Bethesda Transitway 48 Corridor 7: Randolph Road 51 Corridor 8: University Boulevard 54 Corridor 9: US 29 57 Corridor 10: Veirs Mill Road 60 Setting Implementation Priorities for Transit Corridor Improvements 63 Implementation 64 Bicycle and Pedestrian Accommodation and Safety 65 Ensuring Pedestrian Safety and Accessibility 65 Bike Accommodation 65 Bicycle Pedestrian Priority Areas 66 4 MARC Brunswick Line Expansion 73 Carbon -

Why Rapid Transit?

NEW RAPID TRANSIT FOR A GROWING, EQUITABLE ROCHESTER TRANSIT-ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT PLANNING STUDY Phase 2 Public Engagement APRIL 7, 2020 Thank You for Participating during this time of Change The City of Rochester and its partners are committed to addressing immediate community needs. We are also committed to our resilience and success in the future, and advancing work that supports these goals. This engagement process began in February 2020. We are starting the next step in ongoing engagement of community members. Multiple platforms to learn about the project and provide feedback have been provided. We thank everyone for their flexibility and willingness to adapt in an ever-evolving time of change. Engagement and Feedback Engagement: Learning More! Future Webinars: Thursday, April 16th, Tuesday, April 21st. 6:00 PM City of Rochester project webpage: tiny.cc/RochesterTOD • Background on the rapid transit proposal and future steps • Sign up for webinars. • Station Area Plans PDF: area by area analysis and ideas • Interactive “Open House” Webpage and Survey: area by area analysis and ideas using interactive maps • Project Frequently Asked Questions page Engagement and Feedback Feedback: We Need Your Input! • Interactive “Open House” Webpage and Survey : area by area analysis and ideas using interactive maps • Send us an email at: [email protected] • Leave us a voicemail: 507-328-2025 Contents 1. Introduction to the Study 2. Rochester’s growth and the key role of transit 3. Rapid Transit Corridor Segments A. West Gateway 2nd St SW: West Lot to Hwy 52 B. City Corridor 2nd St SW: St Mary’s to 6th Ave C.