Malleefowl (Leipoa Ocellata) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) Environment, Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wyperfeld National Park Track Tobracky Well

Wyperfeld National Park Visitor Guide ‘Dalkaiana wartaty dyadangandak’; We are glad that you have come to our Country. This vast Mallee park is a place of endless space with three distinct landscapes each offereing an new experience: Big Desert country to the west; Mallee to the east; and floodplains and shifting sand dunes to the north. Autumn, winter or spring is the best time to visit and there is plenty of country to cover for 4WD enthusiasts. Snowdrift Day Visitors area is 4WD access only and is set alongside one of the largest white sand dunes in the area. Fireplaces, toilet and tables are available. n o t e s Location and access The park is 450 km north-west of Melbourne and Ornithologist Arthur Mattingly describes Wyperfeld as may be reached; “paradise for nature lovers”. It is a place of tranquillity and inspiration for everyone. • via Patchewollock off the Sunraysia Highway • via Hopetoun on the Henty Highway Welcome to Country • via Underbool on the Mallee Highway ‘As I travel through mallee country I feel the Old • via Rainbow from the Western Highway at People with me and I know I am home.’ Suzie Dimboola. Skurrie, Wotjobaluk. A sealed road gives access from Rainbow or Through their rich culture the Wotjobaluk People Hopetoun to Wonga Campground in the have been intrinsically connected to Country - southern park area - the main camping and including the area now known as Victoria and picnic area. the State’s parks and reserves - for tens of Casuarina Campground, in the northern park thousand of years. area, is reached from Patchewollock by 2WD or Parks Victoria recognises this connection and Underbool along Gunners Track or Wonga by 4WD. -

Malleefowl Facts Dec2016 FINAL

Fauna facts Get to know Western Australia’s fauna Mal leefowl What is a malleefowl? A malleefowl is a bird about the size of a large chicken that lives on the ground and rarely flies. They make nests on the ground, called malleefowl mounds, by heaping together a large mound of soil over a pile of leaves and sticks. Photo: Nye Evans Scientific Name: Leipoa ocellata What do they look and sound like? Other Common Names: gnow, nganamara, lowan, They can be very hard to spot because they native pheasant, incubator or thermometer bird camouflage so well with their natural environment. The wing feathers are grey, black Conservation Status: Vulnerable and white, the belly is creamy, and the neck Threats: vegetation clearing, feral cat and fox and head are grey. predation, fire, road mortality and competition for Malleefowl will often freeze or move quietly food and habitat with sheep, rabbits, cattle and goats. away when disturbed. The male malleefowl Distribution: Semi-arid Mallee ( Eucalyptus ) makes a deep bellowing or loud clucks, while shrublands and woodlands across southern Australia the female makes a high-pitched crowing, soft crooning or low grunting noise. Interesting facts The scientific name means ‘eyelet egg-leaver’ because they have a white ring around their eyes and they bury their eggs in the mound. Malleefowl use their beaks to check the temperature inside the mound, which is why they are also known as thermometer birds and incubator birds. Malleefowl mounds can be as big as 1 metre high and 5 metres wide. Have you seen a malleefowl? The female lays up to 35 eggs and buries them Please tell us if you have seen a malleefowl or inside the nest. -

Parks Victoria Annual Report 2016–17 Acknowledgement of Country

Parks Victoria Annual Report 2016–17 Acknowledgement of Country Aboriginal people, through their rich culture, have been connected to the land and sea, for tens of thousands of years. Parks Victoria respectfully acknowledges Aboriginal Traditional Owners, their cultures and knowledge and their continuing connection to and cultural obligation to care for their Country. Parks and waterways Parks Victoria manages many sites such as piers, waterways, ports, bays, historic buildings, trails, urban parks, small conservation reserves and large national and state parks. For the sake of brevity, these are collectively referred to in this document as ‘parks’, unless a specific type of site is stated. For further information about Parks Victoria and the parks it manages visit www.parks.vic.gov.au or call 13 1963. Copyright © State of Victoria, Parks Victoria 2017 Level 10, 535 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000 ISSN 1448 – 9082 ISSN 1448 – 9090 (online) Published on www.parks.vic.gov.au 2 About Parks Victoria Contents About Parks Victoria 4 Shaping Our Future 6 Healthy Parks Healthy People 7 Chairman’s message 8 Chief Executive Officer’s message 9 Our achievements 10 Strengthening Parks Victoria 12 Connecting people and parks 13 Conserving Victoria’s special places 19 Providing benefits beyond park boundaries 25 Enhancing organisational excellence 31 Compliance and disclosures 41 Compliance with the Australian/New Zealand Risk Management Standard 53 Financial report 54 Parks Victoria Annual Report 2016–17 3 About Parks Victoria Who we are What we manage Parks Victoria commenced operations on 12 December The network of parks that we manage includes 1996 as a statutory authority to manage Victoria’s national parks, marine parks and sanctuaries, diverse parks system. -

Building a National Parks Service for Victoria 1958 – 1975

Building a National Parks Service for Victoria 1958 – 1975 L. H. Smith Norman Bay, at the mouth of Tidal River, looking back to Mt Oberon, where the cover photo was taken, and showing many campers enjoying their holiday. Acknowledgements The publishers wish to acknowledge the assistance of Evelyn Feller in the production of this book, and of Don Saunders, Director of National Parks 1979-1994, in checking the text and captions. Author: Dr Leonard Hart Smith (1910-2004) Editors: Michael Howes, additional editing by Chris Smyth Design: John Sampson, Ecotype Photos: All photos, except where mentioned, are by Dr Leonard Hart Smith. A selection from his extensive 35mm slide collection has been scanned for use in this book. Note: This book is not complete. Dr Len Smith intended to revise it further and add chapters about the other Victorian national parks created during his time as director,1958-1975, but was unable to complete this work. We have published the book as it was written, with only minor corrections. Dr Len Smith was a keen photographer and took thousands of black and white photographs and colour slides. All photos in this book, unless otherwise credited, were taken by Dr Smith. Cover photo: Wilsons Promontory National Park 1973. Hikers at summit of Mt Oberon with Tidal River Campground, Norman Bay, Pillar Point and Tongue Point in background. Disclaimer: The opinions and conclusions in this publication are those of the author, the late Dr Leonard Hart Smith, Director of National Parks in Victoria 1958-1975. The Victorian National Parks Association does not necessarily support or endorse such opinions or conclusions, and takes no responsibility for any errors of fact or any opinions or conclusions. -

P a Rk N O Te S

Wyperfeld National Park Visitor Guide “Welcome to the Mallee. Many visitors to Victoria's outback, including Wyperfeld National Park, fall in love with its beauty and wide-open spaces. The park is best visited in autumn, winter or spring when Emus and Western Grey Kangaroos can be seen grazing at dawn and dusk in the usually dry lakebeds and creeks.” - Ranger In Charge, Kym Schramm Facilities and accommodation Campground facilities include picnic tables, fireplaces, pit toilets, and limited water for drinking and hand washing. General supplies and accommodation are available in Hopetoun, Rainbow, Patchewollock, Walpeup, Underbool and O’Sullivans Pine Plain Lodge. Camping fees n o t e s apply only at Wonga Campground. Nankeen Kestrel Wonga Campground in the southern end of the The park is of interest to naturalists, particularly park is spacious and has a Visitor Information birdwatchers. Ornithologist Arthur Mattingly describes it as “paradise for nature lovers”. It is a place of Centre, three self - guided interpretive walks, a tranquillity and inspiration for everyone. scenic nature drive and basic camping facilities. Things to see and do Casuarina Campground in the northern Pine Plains area of the park is set amid Pine - Buloke Parks provide a multitude of activities for visitors woodlands and vast open lakebeds surrounded to enjoy. Camping, fishing, touring, bushwalking, by Mallee sand dunes and a circular-walking mountain biking, or 4WD , there’s something for track to Bracky Well. Snowdrift Day Visitors area everyone. is 4WD access only and is set alongside one of the largest white sand dunes in the area. Fireplaces, toilet and tables are available. -

National Parks Act Annual Report 2019–20 1 Contents

NATIONAL PARKS ACT ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 Traditional Owner Acknowledgement Victoria’s network of parks and reserves form the core of Aboriginal cultural landscapes, which have been modified over many thousands of years of occupation. They are reflections of how Aboriginal people engaged with their world and experienced their surroundings and are the product of thousands of generations of economic activity, material culture and settlement patterns. The landscapes we see today are influenced by the skills, knowledge and activities of Aboriginal land managers. Parks Victoria acknowledges the Traditional Owners of these cultural landscapes, recognising their continuing connection to Victoria’s parks and reserves and their ongoing role in caring for Country. Copyright © State of Victoria, Parks Victoria 2020 Level 10, 535 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000 ISSN 2652-3183 (print) ISSN 2652-3191 (online) Published on www.parks.vic.gov.au This report was printed on 100% recycled paper. This publication may be of assistance to you but Parks Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication Notes • During the year the responsible Minister for the Act was the Hon Lily D’Ambrosio MP, Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change. • In this report: – the Act means the National Parks Act 1975 – DELWP means the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning – the Minister means the Minister responsible for administering the Act – the Regulations means the National Parks Regulations 2013 – the Secretary means the Secretary to the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. -

See Prunella Modularis Acrocephalus Schoenobaenus

INDEX An "/" or a "t" suffix indicates that a term may be found in a figure or table on the page indi cated. Accentor, Hedge: see Prunella modularis A1ca torda (Razorbill), 46t, 206t Accipiter gentilis (Northern Goshawk), 43t Alcedo atthis (Common Kingfisher), 45t A. nisus (Sparrowhawk), 7, 43t, 204t Alectoris rufa (Red-legged Partridge), Acrocephalus schoenobaenus (Sedge 112t,118t Warbler), 208t Allee effect, 170, 175 A. scirpaceus (Reed Warbler), 208t American Avocet: see Recurvirostra Actitis macularia (Spotted Sandpiper), americana 204t 213-215, 227-228 American Black Duck: see Anas rubripes Adjacent habitat, response of brood para American Crow: see Corvus sites to, 294, 299 brachyrhynchos Aegolius funereus (Boreal Owl), 42t, 50, 227 American Dipper: see Cinclus mexicanus Agelaius phoeniceus (Red-winged Black American Golden Plover: see Pluvialis bird), 16, 39, 44t, 90t, 106, 112t, dominica 113t, 114, 129t, 209t, 229, 264, American Goldfinch: see Carduelis tristis 281,283 American Kestrel: see Falco sparverius Air ions, as cue of advancing winter American Pipit: see Anthus rubescens storm, 24 American Redstart: see Setophaga Aix sponsa (Wood Duck), 45t, 122t, 234 ruticilla Alauda arvensis (Eurasian Skylark), 47t, 90t American Tree Sparrow: see Spizella Albatross, 163 arborea Black-browed: see Diomedea American Wigeon: see Anas americana melanophris American Woodcock: see Scolopax minor Gray-headed: see Diomedea Anas acuta (Northern Pintail), 4lt, 51, 123t chrysostoma A. americana (American Wigeon), 4lt, Laysan: see Diomedea immutabilis 122t Royal: see Diomedea epomophora A. capensis (Cape Teal), 122t Sooty: see Phoebetria fusca A. castanea (Chestnut Teal), 123t Wandering: see Diomedea exulans A. clypeata (Northern Shoveler), 41t, Waved: see Diomedea irrorata 113t, 123t 311 312 INDEX Anas acuta (Northern Pintail) (cont.) Arrival-time advantage, different mi A. -

Download the Bird List

Bird list for MESSENT CONSERVATION PARK -36.05729 °N 139.77199 °E 35°03’26” S 139°46’19” E 54 389400 6090000 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Red-necked Avocet Laughing Kookaburra Rainbow Bee-eater Banded Lapwing Eastern Bluebonnet Musk Lorikeet Australian Boobook Purple-crowned Lorikeet Brush Bronzewing Malleefowl Common Bronzewing Black-tailed Nativehen Little Buttonquail Spotted Nightjar Painted Buttonquail Eastern Barn Owl Cockatiel Australian Owlet-nightjar Great Cormorant Blue-winged Parrot Little Black Cormorant Elegant Parrot Pied Cormorant Red-rumped Parrot Australian Crake Australian Pelican Fan-tailed Cuckoo Crested Pigeon Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo *Feral Pigeon Pallid Cuckoo Red-capped Plover Black-fronted Dotterel Spur-winged Plover Red-kneed Dotterel (Masked Lapwing) Peaceful Dove Brown Quail Blue-billed Duck Stubble Quail Maned Duck Mallee Ringneck Musk Duck (Australian Ringneck) Pacific Black Duck Crimson Rosella Wedge-tailed Eagle Eastern Rosella Great Egret Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Emu Australian Shelduck Brown Falcon Latham's Snipe Peregrine Falcon Collared Sparrowhawk Tawny Frogmouth Royal Spoonbill Galah Yellow-billed Spoonbill Brown Goshawk Pied Stilt Australasian Grebe Black Swan Great Crested Grebe Chestnut Teal Hoary-headed Grebe Grey Teal Silver Gull Whiskered Tern Hardhead Spotted Harrier Swamp Harrier Nankeen Night Heron White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Australian White Ibis Nankeen Kestrel Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. -

National Parks Act Annual Report 2013

National Parks Act Annual Report 2013 Authorised and published by the Victorian Government Department of Environment and Primary Industries, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne September 2013 © The State of Victoria, Department of Environment and Primary Industries 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Printed by Finsbury Green ISSN 1839-437X ISSN 1839-4388 (online) Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, please telephone the DEPI Customer Service Centre on 136 186, email [email protected], or via the National Relay Service on 133 677 or www.relayservice.com.au. This document is also available on the internet at www.depi.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Further information For further information, please contact the DEPI Customer Service Centre on 136 186 or the Parks Victoria Information Centre on 131 963. Notes • The Minister responsible for administering the National Parks Act 1975 during the year was the Hon Ryan Smith MP, Minister for Environment and Climate Change. • In this report: - the legislation referred to is Victorian -

Australia ‐ Part One 2017

Field Guides Tour Report Australia ‐ Part One 2017 Oct 9, 2017 to Oct 29, 2017 Chris Benesh & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Simpsons Gap, well captured in early morning light by Cliff Hensel. We started off the tour in Sydney with a visit to Centennial Park, where we were fortunate to meet up with Steve Howard, who took us to several of his favorite birding sites and got us onto a Powerful Owl which would have otherwise been impossible to find. Several of us also enjoyed feeding figs to a Common Brushtail Possum roosting in the area. We then headed over to the Sydney Botanical Garden for another Powerful Owl and a nice view of the Sydney harbour. The next morning, we headed over to Royal National Park and had a great morning walking along the Lady Carrington Drive. Lots of wonderful birds, with Superb Lyrebird being the most memorable. After a cafe lunch, we tracked down a wonderful pair of Rockwarblers. After our flight to Melbourne, we headed to the Western Treatment Plant for a tour with Paul. We had a great tour of Werribee, with some good shorebird action and a nice mix of ducks and waterbirds. From there we made our way back to St. Kilda, and an evening visit to the harbor to watch Little Penguins come ashore. The following morning we made a brief stop at the Serendip Sanctuary to see the Cape Barren Geese before heading on to Pt. Addis on the Great Ocean Road, where we had fantastic views of a Rufous Bristlebird family. -

Supplementary Methods S1

1 Validation methods for trophic niche models 2 3 To assign links between nodes (species), we used trophic niche-space models (e.g., [1]). 4 Each of these models has two quantile regressions that define the prey-size range a 5 predator of a given size is predicted to consume. Species whose body mass is within the 6 range of a predator’s prey size, as identified by the trophic niche-space model, are predicted 7 to be prey, while those outside the range are predicted not to be eaten. 8 9 The broad taxonomy of a predator helps to predict predation interactions [2]. To optimize 10 our trophic niche-space model, we therefore tested whether including taxonomic class of 11 predators improved the fit of quantile regressions. Using trophic (to identify which species 12 were predators), body mass, and taxonomic data, we fitted and compared five quantile 13 regression models (including a null model) to the GloBI data. In each model, we log10- 14 transformed the dependent variable prey body mass, and included for the independent 15 variables different combinations of log10-transformed predator body mass, predator class, 16 and the interaction between these variables (Supplementary Table S4). We log10- 17 transformed both predator and prey body mass to linearize the relationship between these 18 variables. We fit the five quantile regressions to the upper and lower 5% of prey body mass, 19 and compared model fits using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The predator body 20 mass*predator class model fit the 95th quantile data best, whereas the predator body mass 21 + predator class model fit the 5th quantile data marginally better than the aforementioned 22 interaction model (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S4). -

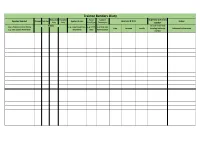

Trainee Bander's Diary (PDF

Trainee Banders Diary Extracted Handled Band Capture Supervising A-Class Species banded Banded Retraps Species Groups Location & Date Notes Only Only Size/Type Techniques Bander Totals Include name and Use CAVS & Common Name e.g. Large Passerines, e.g. 01AY, e.g. Mist-net, Date Location Locode Banding Authority Additional information e.g. 529: Superb Fairy-wren Shorebirds 09SS Hand Capture number Reference Lists 05 SS 10 AM 06 SS 11 AM Species Groups 07 SS 1 (BAT) Small Passerines 08 SS 2 (BAT) Large Passerines 09 SS 3 (BAT) Seabirds 10 SS Shorebirds 11 SS Species Parrots and Cockatoos 12 SS 6: Orange-footed Scrubfowl Gulls and Terns 13 SS 7: Malleefowl Pigeons and Doves 14 SS 8: Australian Brush-turkey Raptors 15 SS 9: Stubble Quail Waterbirds 16 SS 10: Brown Quail Fruit bats 17 SS 11: Tasmanian Quail Ordinary bats 20 SS 12: King Quail Other 21 SS 13: Red-backed Button-quail 22 SS 14: Painted Button-quail Trapping Methods 23 SS 15: Chestnut-backed Button-quail Mist-net 24 SS 16: Buff-breasted Button-quail By Hand 25 SS 17: Black-breasted Button-quail Hand-held Net 27 SS 18: Little Button-quail Cannon-net 28 SS 19: Red-chested Button-quail Cage Trap 31 SS 20: Plains-wanderer Funnel Trap 32 SS 21: Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Clap Trap 33 SS 23: Superb Fruit-Dove Bal-chatri 34 SS 24: Banded Fruit-Dove Noose Carpet 35 SS 25: Wompoo Fruit-Dove Phutt-net 36 SS 26: Pied Imperial-Pigeon Rehabiliated 37 SS 27: Topknot Pigeon Harp trap 38 SS 28: White-headed Pigeon 39 SS 29: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Band Size 03 IN 30: Peaceful Dove 01 AY 04 IN 31: Diamond