HV Chapter 28-Entrapment Neuropathies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piriformis Syndrome Is Overdiagnosed 11 Robert A

American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine AANEM CROSSFIRE: CONTROVERSIES IN NEUROMUSCULAR AND ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC MEDICINE Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Robert A.Werner, MD, MS Scott J. Primack, DO Willam S. Pease, MD Ernest W. Johnson, MD Lawrence R. Robinson, MD 2005 AANEM COURSE F AANEM 52ND Annual Scientific Meeting Monterey, California CROSSFIRE: Controversies in Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Robert A.Werner, MD, MS Scott J. Primack, DO Willam S. Pease, MD Ernest W. Johnson, MD Lawrence R. Robinson, MD 2005 COURSE F AANEM 52nd Annual Scientific Meeting Monterey, California AANEM Copyright © September 2005 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 421 First Avenue SW, Suite 300 East Rochester, MN 55902 PRINTED BY JOHNSON PRINTING COMPANY, INC. ii CROSSFIRE: Controversies in Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine Faculty Loren M. Fishman, MD, B.Phil Scott J. Primack, DO Assistant Clinical Professor Co-director Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Colorado Rehabilitation and Occupational Medicine Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons Denver, Colorado New York City, New York Dr. Primack completed his residency at the Rehabilitation Institute of Dr. Fishman is a specialist in low back pain and sciatica, electrodiagnosis, Chicago in 1992. He then spent 6 months with Dr. Larry Mack at the functional assessment, and cognitive rehabilitation. Over the last 20 years, University of Washington. Dr. Mack, in conjunction with the Shoulder he has lectured frequently and contributed over 55 publications. His most and Elbow Service at the University of Washington, performed some of the recent work, Relief is in the Stretch: End Back Pain Through Yoga, and the original research utilizing musculoskeletal ultrasound in order to diagnose earlier book, Back Talk, both written with Carol Ardman, were published shoulder pathology. -

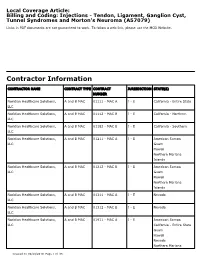

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: a Still Challenge Condition

Rev Bras Neurol. 55(1):12-17, 2019 TARSAL TUNNEL SYNDROME: A STILL CHALLENGE CONDITION SÍNDROME DO TÚNEL DO TARSO: UMA CONDIÇÃO AINDA DESAFIADORA Celmir de Oliveira Vilaça1,2, Bruno Pessoa3, Janaína de Moraes Silva4, Victor Hugo Bastos5, Diandra Martins5, Silmar Teixeira6, Victor Marinho6, Rossano Fiorelli7, Vanessa de Albuquerque Dinoa8; Marco Orsini7, 9 ABSTRACT RESUMO Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a rare, under diagnosed and often confu- A Síndrome do túnel do tarso é uma rara e subdiagnosticada neuro- sed neuropathy with other clinical entities. There is a lack of popula- patia geralmente confundida com outras entidades clínicas. Há falta tion studies on this disease. Herein, we performed a non-systematic de estudos populacionais sobre a doença. Assim sendo, realizamos review of articles between January 1992 and February 2018. Althou- uma revisão da literatura de artigos entre Janeiro de 1992 e fevereiro gh with a less complex anatomy comparing to the carpal tunnel, the de 2018. Apesar de possuir uma anatomia de menor complexidade tarsal tunnel is source of pain and some other conditions. Treatment comparada ao túnel do carpo, o túnel do tarso é origem de dor e involves conservative measures such as analgesics and physical the- algumas outras condições. O tratamento envolve medidas conserva- rapy rehabilitation or surgical procedures in case of conservative doras como analgésicos e terapia de reabilitação ou procedimentos treatment failure. Randomized control studies are lack and manda- cirúrgicos, em caso de falha do tratamento conservador. Estudos ran- tory for uncover the best modality of treatment for this condition. domizados são escassos e necessários para descoberta da melhor modalidade de tratamento desta condição. -

Plantar Fasciitis Exercises

Accurate Clinic 2401 Veterans Memorial Blvd. Suite16 Kenner, LA 70062 - 4799 Phone: 504.472.6130 Fax: 504.472.6128 www.AccurateClinic.com Plantar Fasciitis Exercise Getting the right plantar fasciitis exercise is imperative to ensure the injury doesn’t continue to affect performance. If not given the attention it needs, plantar fasciitis can flair up long after an athlete thinks they’ve recovered and badly damage training plans and competition aspirations. What is plantar fascia? Plantar fascia is a thick, fibrous band of connective tissue which originates at the heel bone and runs along the bottom of the foot in a fan-like manner, attaching to the base of each of the toes. A rather tough, resilient structure, the plantar fascia takes on a number of critical functions during running and walking. Although the fascia is invested with countless sturdy 'cables' of connective tissue called collagen fibres, it is certainly not immune to injury. In fact, about 5 to 10 per cent of all running injuries are inflammations of the fascia, an incidence rate which in the United States would produce about a million cases of plantar fasciitis per year, just among runners and joggers. Basketball players, tennis players, volleyballers, step-aerobics participants, and dancers are also prone to plantar problems, as are non-athletic people who spend a lot of time on their feet or suddenly become active after a long period of lethargy. Why does the fascia flare up? Although it is a fairly rugged structure, the plantar fascia is not very receptive to stretching, and yet stretching occurs in the fascia nearly every time the foot hits the ground. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Secondary to the Posterior Tibial Nerve Schwannoma

Case Report http://dx.doi.org/10.12972/The Nerve.2015.01.01.034 www.thenerve.net Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Secondary to the Posterior Tibial Nerve Schwannoma Jung Won Song1, Sung Han Oh1, Pyung Goo Cho1, Eun Mee Han2 Departments of 1Neurosurgey, 2Pathology, Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital, Seongnam, Korea A 77-year-old female presented with complaint of burning pain and paresthesia along the medial aspect of ankle, heel and sole of the left foot. An ankle MRI, electromyelogram (EMG) with nerve conduction velocity (NCV) and pathologic findings were all compatible with Tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by the posterior tibial nerve Schwannoma. Operative release of the Tarsal tunnel and surgical excision of Schwannoma were performed under the microscopy. It is necessary to have a possible lump in mind when Tarsal tunnel syndrome is suspected, such as posterior tibial nerve Schwannoma. Key Words: Posterior Tibial NerveㆍSchwannomaㆍTarsal Tunnel Syndrome diagnose neurofibromatosis was insufficient. An ankle magne- tic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed about a 22×19×9 mm- INTRODUCTION sized ovoid soft tissue mass in the posterior ankle connected to the posterior tibial nerve. The mass lies beneath the flexor Although Schwannomas are the most common peripheral retinaculum of ankle and showed relatively strong enhance- nerve sheath tumor, Schwannoma of the posterior tibial nerve ment (Fig. 1). and it branch is a rare etiology causing Tarsal tunnel syndrome. The NCV study showed no response sensory nerve action We report a case of Tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by the pos- potentials of the left medial and lateral plantar nerves. Motor terior tibial nerve Schwannoma and mention surgical strategy conduction study of the deep peroneal and tibial nerves was with literature review. -

Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Tarsal-Tunnel Syndrome

CLEVELAND CLINIC QUARTERLY Volume 37, January 1970 Copyright © 1970 by The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Printed in U.S.A. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of the tarsal-tunnel syndrome THOMAS E. GRETTER, M.D. Department o£ Neurology ALAN H. WILDE, M.D. Department of Orthopaedic Surgery N recent years many peripheral nerve compression syndromes have been I recognized. The carpal-tunnel syndrome, or compression of the median nerve at the wrist beneath the transverse carpal ligament, is the com- monest nerve entrapment syndrome. Less familiar but no less important is the tarsal-tunnel syndrome. Since the first case reports of the tarsal-tunnel syndrome by Keck1 and by Lam,2 in 1962, this syndrome is being diag- nosed with increasing frequency. Within the last two years 17 patients with the tarsal-tunnel syndrome have been treated at the Cleveland Clinic. Our report presents a review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of the tarsal-tunnel syndrome. Anatomy The tarsal tunnel is a canal formed on the medial side of the foot and ankle by the medial malleolus of the tibia and the flexor retinaculum. The flexor retinaculum spans the medial malleolus of the tibia and the medial tubercle of the os calcis (Fig. 1). The space beneath the ligament is divided by septae into four compartments. Each compartment contains one of the four structures of the tarsal tunnel. These structures are the pos- terior tibial tendon, flexor digitorum longus tendon, posterior tibial nerve, artery and veins, and the flexor hallucis longus tendon. Each tendon is invested with a separate synovial sheath. -

Foot and Ankle Disorders Capturing Motion with Ultrasound

VISIT THE AANEM MARKETPLACE AT WWW.AANEM.ORG FOR NEW PRODUCTS AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF NEUROMUSCULAR & ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC MEDICINE Foot and Ankle Disorders Capturing Moti on With Ultrasound: Blood, Muscle, Needle, and Nerve Photo by Michael D. Stubblefi eld, MD Foot and Ankle Nerve Disorders Tracy A. Park, MD David R. Del Toro, MD Atul T. Patel, MD, MHSA Jeffrey A. Mann, MD AANEM 58th Annual Meeting San Francisco, California Copyright © September 2011 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 Printed by Johnson’s Printing Company, Inc. 1 Please be aware that some of the medical devices or pharmaceuticals discussed in this handout may not be cleared by the FDA or cleared by the FDA for the specific use described by the authors and are “off-label” (i.e., a use not described on the product’s label). “Off-label” devices or pharmaceuticals may be used if, in the judgment of the treating physician, such use is medically indicated to treat a patient’s condition. Information regarding the FDA clearance status of a particular device or pharmaceutical may be obtained by reading the product’s package labeling, by contacting a sales representative or legal counsel of the manufacturer of the device or pharmaceutical, or by contacting the FDA at 1-800-638-2041. 2 Foot and Ankle Nerve Disorders Table of Contents Course Objectives & Course Committee 4 Faculty 5 Tarsal Tunnel Syndromes 7 Tracy A. Park, MD First Branch Lateral Plantar Neuropathy: “Baxter’s Neuropathy” 17 David R. Del Toro, MD Foot Pain Related to Peroneal (Fibular) Nerve Entrapments (Deep and Superficial) and Digital Neuromas 25 Atul T. -

Posterior Compartment of the Lower

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Leg Posterior Compartment Authors Evan Mostafa1; Matthew Varacallo2. Affiliations 1 Albert Einstein College of Medicine 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Kentucky School of Medicine Last Update: January 2, 2019. Introduction The lower leg divides into three fascial compartments: Anterior Lateral Posterior These compartments are formed and separated via divisions by the anterior and posterior intermuscular septa, and the interosseous membrane.[1] Each compartment contains its distinct set of muscles, vasculature, and innervation: The anterior compartment musculature functions to primarily dorsiflex the foot and ankle The lateral compartment musculature functions to plantar flex and evert the foot The posterior compartment musculature functions to plantarflex and invert the foot The posterior compartment of the leg (often referred to as the "calf") further divides into distinct superficial and deep compartments by the transverse intermuscular septum. The larger, superficial compartment of the lower leg contains the gastrocnemius, soleus (GS) and plantaris muscles. The deep layer of the leg's posterior compartment contains the popliteus, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis posterior muscles. The various muscles of the posterior compartment primarily originate at the two bones of the leg, the tibia, and the fibula. The tibia is a large weight-bearing bone, often referred to as the "shin bone," and articulates with the femoral condyles superiorly and the talus inferiorly.[2] The fibula articulates with the tibia laterally at proximal and distal ends; however, it has no involvement in weight bearing.[3] Structure and Function The divisions of the lower leg are made up by intermuscular septa that are extensions of the overlying fascia. -

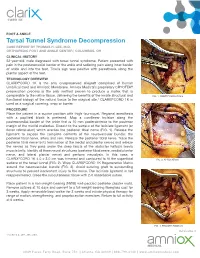

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Decompression AS DESCRIBED by THOMAS H

FOOT & ANKLE Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Decompression AS DESCRIBED BY THOMAS H. LEE, M.D. ORTHOPEDIC FOOT AND ANKLE CENTER | COLUMBUS, OH TECHNOLOGY PLATFORM CLARIX®CORD 1K Regenerative Matrix is cryopreserved human Amniotic Membrane and Umbilical Cord (hAMUC). Amniox Medical’s proprietary CRYOTEK® preservation process retains the relevant natural structural and biological characteristics of the hAMUC tissue while devitalizing the living cells. CLARIX®CORD 1K Regenerative Matrix is used as a surgical covering, wrap or barrier. CLINICAL HISTORY 52-year-old, male diagnosed with tarsal tunnel syndrome. Patient presented with pain in FIG. 1: IDENTIFY EXOSTOSIS the posteromedial border of the ankle and radiating pain along inner border of ankle and into the foot. Tinel’s sign was positive with paresthesia along the plantar aspect of the foot. PROCEDURE Place the patient in a supine position with thigh tourniquet. Regional anesthesia with a popliteal block is preferred. Map a curvilinear incision along the posteromedial border of the ankle that is 10 mm posteroinferior to the posterior margin of the medial malleolus. Dissect to the surface of the laciniate ligament (or flexor retinaculum) which overlies the posterior tibial nerve (FIG. 1). Release the ligament to expose the complete contents of the neurovascular bundle: the posterior tibial nerve, artery and vein. Release the posterior tibial nerve. Trace the posterior tibial nerve to its termination at the medial and plantar nerves and release the nerves as they pass under the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis brevis muscle belly. Identify all three neural structures (posterior tibial nerve, medial plantar nerve, and lateral plantar nerve) and perform neurolysis. -

Macroscopic Observations of Muscular Bundles of Accessory Iliopsoas Muscle As the Cause of Femoral Nerve Compression T

Journal of Orthopaedics 16 (2019) 64–68 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Orthopaedics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jor Macroscopic observations of muscular bundles of accessory iliopsoas muscle as the cause of femoral nerve compression T ∗ Fuat Unat, Suzan Sirinturk, Pınar Cagimni, Yelda Pinar, Figen Govsa , Gkionoul Nteli Chatzioglou Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Ege University, Izmir, Turkey ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Compression of the femoral nerve (FN) to the iliac fossa has been reported as a consequence of several Femoral nerve pathologies as well as due to the aberrant muscles. The purpose of this research was to investigate the patterns of Iliacus muscle the accessory muscles of iliopsoas muscles and the relationship of the FN in fifty semi pelvis. Accessory muscular Psoas major muscle slips from iliacus and psoas, piercing or covering the FN, were found in 19 specimens (7.9%). Based on the Entrapment syndrome macroscopic structure, the muscle was categorized into two types. Pattern 1 as the more frequent variation, was Leg pain sheet muscular type covering the FN (17 specimens, 89.5%). Pattern 2, the less frequent variation was found on a Neuropathic pain Compression muscular slip covering the FN (2 specimens, 10.5%). Iliac and psoas muscles and their variants on both types Muscular variations were defined. Appraising the relation between the muscle and the nerves, each disposition of the patterns may be Peripheral nerve stimulation a potential risk for nerve entrapment. The knowledge about the possible variations of the iliopsoas muscle complex and the FN may also give surgeons confidence during pelvic surgery. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Secondary to Osteochondroma of the Calcaneus

Won et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2020) 21:491 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03530-9 CASE REPORT Open Access Tarsal tunnel syndrome secondary to osteochondroma of the calcaneus: a case report Sung Hun Won1†, Jahyung Kim2†, Tae-Hong Min2, Dong-Il Chun2, Young Yi3, Sang Hak Han4 and Jaeho Cho5* Abstract Background: Tarsal tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy that can be provoked by either intrinsic or extrinsic factors that compresses the posterior tibial nerve beneath the flexor retinaculum. Osteochondroma, the most common benign bone tumor, seldom occur in foot or ankle. This is a rare case of tarsal tunnel syndrome secondary to osteochondroma of the sustentaculum tali successfully treated with open surgical excision. Case presentation: A 15-year-old male presented with the main complaint of burning pain and paresthesia on the medial plantar aspect of the forefoot to the middle foot region. Hard mass-like lesion was palpated on the posteroinferior aspect of the medial malleolus. On the radiological examination, 2.5 × 1 cm sized bony protuberance was found below the sustentaculum tali. Surgical decompression of the posterior tibial nerve was performed by complete excision of the bony mass connected to the sustentaculum tali. The excised mass was diagnosed to be osteochondroma on the histologic examination. After surgery, the pain was relieved immediately and hypoesthesia disappeared 3 months postoperatively. Physical examination and radiographic examination at 2-year follow up revealed that tarsal tunnel was completely decompressed without any evidence of complication or recurrence. Conclusions: As for tarsal tunnel syndrome secondary to the identifiable space occupying structure with a distinct neurologic symptom, we suggest complete surgical excision of the causative structure in an effort to effectively relieve symptoms and prevent recurrence. -

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Decompression CASE REPORT by THOMAS H

FOOT & ANKLE Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Decompression CASE REPORT BY THOMAS H. LEE, M.D. ORTHOPEDIC FOOT AND ANKLE CENTER | COLUMBUS, OH CLINICAL HISTORY 52-year-old, male diagnosed with tarsal tunnel syndrome. Patient presented with pain in the posteromedial border of the ankle and radiating pain along inner border of ankle and into the foot. Tinel’s sign was positive with paresthesia along the plantar aspect of the foot. TECHNOLOGY OVERVIEW CLARIX®CORD 1K is the only cryopreserved allograft comprised of human Umbilical Cord and Amniotic Membrane. Amniox Medical’s proprietary CRYOTEK® preservation process is the only method proven to produce a matrix that is comparable to the native tissue, delivering the benets of the innate structural and FIG. 1: IDENTIFY EXOSTOSIS functional biology of the natural tissue to the surgical site.¹ CLARIX®CORD 1K is used as a surgical covering, wrap or barrier. PROCEDURE Place the patient in a supine position with thigh tourniquet. Regional anesthesia with a popliteal block is preferred. Map a curvilinear incision along the posteromedial border of the ankle that is 10 mm posteroinferior to the posterior margin of the medial malleolus. Dissect to the surface of the laciniate ligament (or exor retinaculum) which overlies the posterior tibial nerve (FIG. 1). Release the ligament to expose the complete contents of the neurovascular bundle: the posterior tibial nerve, artery and vein. Release the posterior tibial nerve. Trace the posterior tibial nerve to its termination at the medial and plantar nerves and release the nerves as they pass under the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis brevis muscle belly.