An Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 215 NJS Presents Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Historic Preservation Fund

CHAPTER 97 AN ACT appropriating $10,250,780 from the “2009 Historic Preservation Fund” and the “2007 Historic Preservation Fund” for the purpose of providing grants, as awarded by the New Jersey Historic Trust, for certain historic preservation projects, and appropriating $600,000 from the “2009 Historic Preservation Fund” for associated administrative expenses. BE IT ENACTED by the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: 1. a. There is appropriated to the New Jersey Historic Trust the following sums for the purpose of providing capital preservation grants as listed in subsection b. of this section and historic site management grants as listed in subsection c. of this section, as awarded by the New Jersey Historic Trust, for historic preservation projects approved as eligible for such funding: (1) $8,120,541 from the “2009 Historic Preservation Fund,” established pursuant to section 20 of the “Green Acres, Water Supply and Floodplain Protection, and Farmland and Historic Preservation Bond Act of 2009,” P.L.2009, c.117; and (2) $2,130,239 from the “2007 Historic Preservation Fund,” established pursuant to section 20 of the “Green Acres, Farmland, Blue Acres, and Historic Preservation Bond Act of 2007,” P.L.2007, c.119. b. The following historic preservation projects are eligible for funding in the form of capital preservation grants, as awarded by the New Jersey Historic Trust, using moneys appropriated pursuant to subsection a. of this section: County Municipality Name of Project Name Grant Organization Award Atlantic Linwood City Linwood City Linwood Borough School #1 $47,199 Bergen Oradell Boro Bergen Co. -

Garden State Preservation Trust

COVERCOVERcover Garden State Preservation Trust DRAFT Annual Report INCOMPLETE FISCAL YEAR 2011 This is a director's draft of the proposed FY2011 Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust. This draft report is a work-in- progress. This draft has neither been reviewed nor approved by the chairman or members of the GSPT board. The director's draft is being posted in parts as they are completed to make the information publicly available pending submission, review and final approval by the GSPT board. Garden State Preservation Trust Fiscal Year 2011 DRAFT Annual Report This is the Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the Fiscal Year 2011 from July 1, 2010 to June 30, 2011. It has always been goal and mission of the Garden State Preservation Trust to place preservation first. This report reflects that priority. The most common suggestion concerning prior annual reports was to give more prominent placement to statistics about land preservation. This report is structured to place the preservation data first and to provide it in unprecedented detail. Information and financial data concerning GSPT financing, recent appropriations and agency operations are contained in the chapters which follow the acreage tables. This is to be construed as the full annual report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the 2011 Fiscal Year in compliance with P.L. 1999 C.152 section 8C-15. It is also intended to be a comprehensive summary of required financial reporting from FY2000 through FY2011. This document updates the financial and statistical tables contained in prior annual reports. -

I. Goals and Objectives Ii. Land Use Plan

I. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES GOALS ........................................................................................................................................................ I-2 OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................................................. I-3 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................. I-3 Housing.................................................................................................................................................... I-7 Circulation ................................................................................................................................................ I-8 Economic Development ......................................................................................................................... I-10 Utilities ................................................................................................................................................... I-11 Conservation ......................................................................................................................................... I-12 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................................. I-13 Parks and Recreation ........................................................................................................................... -

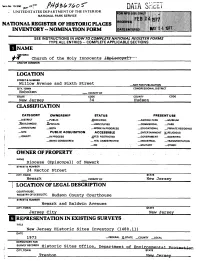

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

sormNo. 10-300 ,. \0- \$sfl- . UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME ORIC Church of the Holy Innocents AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Willow Avenue and Sixth Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hoboken == VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New Jersey 34 Hudson CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -XOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XBUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT ^.RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO •-.-.. —Ml LITAR Y —OTHER : OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Diocese (Episcopal) of Newark STREET & NUMBER 24 Rector Street CITY. TOWN Newark VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Hudson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Newark and Baldwin Avenues CITY. TOWN Jersey Gity REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE New Jersey Historic Sites Inventory (1480.11) DATE 1973 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic sites Qffice , Department of Envirnnmgr>+a i CITY. TOWN STATE .Trenton DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.GOOD _RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Church of the Holy Innocents was erected in 1872 by Edward Tuckerman Potter in the High Gothic style. Intended to be cruciform with a seating capacity of some 600 people the plans were never carried out completely. In 1895 Church of the Holy Innocents was significantly enlarged to the rear by architect Henry Vaughan. -

Htannualreport2011 FINAL.Indd

You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library PRESERVING CENTURIES OF NEW JERSEY HISTORY 2011ANNUAL REPORT You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library CONTENTS Message from DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY AFFAIRS 3 Message from NEW JERSEY HISTORIC TRUST 4 BOARD OF TRUSTEES AND STAFF 5 Year In Review - 2011 HISTORIC PRESERVATION AWARDS 7 Year In Review - 2011 CONFERENCE 9 Year In Review - 2011 PUBLIC OUTREACH AND EVENTS 12 Year In Review - 2011 NEW INITIATIVES 13 Year In Review - 2011 COMPLETED PROJECTS 14 Grants Awarded: GOVERNOR CHRISTIE’S BILL-SIGNING REMARKS 19 Grants Awarded: GARDEN STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION TRUST FUND 21 Grants Awarded: 1772 FOUNDATION 27 Completed Projects on page 14 ABOUT THE NEW JERSEY HISTORIC TRUST 29 201ANNUAL REPORT 1 Governor Christie’s Bill-Signing Remarks on page 19 New Funded Projects beginning on page 21 You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library ANNUALMessage REPORT from the 2DEPARTMENT011 OF COMMUNITY AFFAIRS Dear Friends and Supporters: As you browse through the pages of this beautiful testimony to the important preservation work going on throughout the state, you will discover that the reach of We are pleased to bring you the 2011 New Jersey Historic Trust Annual Report. As the our mission touches everything from churches and schools, to farmsteads and parks. state’s leading voice for historic preservation, the Trust has accomplished so much this I encourage you to visit these wonderful historic and cultural sites and experience for past year and continues to pursue the preservation of our state’s most valuable historic yourselves the excellent work done by preservationists. -

Htannualreport2011 FINAL.Indd

PRESERVING CENTURIES OF NEW JERSEY HISTORY 2011ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Message from DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY AFFAIRS 3 Message from NEW JERSEY HISTORIC TRUST 4 BOARD OF TRUSTEES AND STAFF 5 Year In Review - 2011 HISTORIC PRESERVATION AWARDS 7 Year In Review - 2011 CONFERENCE 9 Year In Review - 2011 PUBLIC OUTREACH AND EVENTS 12 Year In Review - 2011 NEW INITIATIVES 13 Year In Review - 2011 COMPLETED PROJECTS 14 Grants Awarded: GOVERNOR CHRISTIE’S BILL-SIGNING REMARKS 19 Grants Awarded: GARDEN STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION TRUST FUND 21 Grants Awarded: 1772 FOUNDATION 27 Completed Projects on page 14 ABOUT THE NEW JERSEY HISTORIC TRUST 29 201ANNUAL REPORT 1 Governor Christie’s Bill-Signing Remarks on page 19 New Funded Projects beginning on page 21 ANNUALMessage REPORT from the 2DEPARTMENT011 OF COMMUNITY AFFAIRS Dear Friends and Supporters: As you browse through the pages of this beautiful testimony to the important preservation work going on throughout the state, you will discover that the reach of We are pleased to bring you the 2011 New Jersey Historic Trust Annual Report. As the our mission touches everything from churches and schools, to farmsteads and parks. state’s leading voice for historic preservation, the Trust has accomplished so much this I encourage you to visit these wonderful historic and cultural sites and experience for past year and continues to pursue the preservation of our state’s most valuable historic yourselves the excellent work done by preservationists. resources. Finally, I want to thank and recognize the outstanding work of the New Jersey Historic Th is report highlights the many outstanding historic preservation planning projects Trust staff and board. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

QMS Approval No. 1024-0018 NFS Form 10-900-a (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 05000884 Date Listed: 8/16/06 Van Wagenen House Hudson NJ Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination entation. 'Signature of the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: The nomination is amended to change the Area of Significance for Archeology from "Historic-non- aboriginal" to "Archeology-Historic-Non-Aboriginal" DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct 1990) United States Department of the Int rrtor National Park Service RECEIVED 2280 National Register of Histc ric Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting deter districts. See instructions' ' to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register, "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documei ons, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________ historic name Van Wagenen House_____ other names/site number Apple Tree House 2. -

1 Cleary Giacobbe Alfieri Jacobs, LLC Ruby Kumar

HUD-L-000607-18 09/20/2018 4:04:44 PM Pg 1 of 3 Trans ID: LCV20181638897 Cleary Giacobbe Alfieri Jacobs, LLC Ruby Kumar-Thompson, Esq. (Attorney ID No. 044951999) 169 Ramapo Valley Road Upper Level – Suite 105 Oakland, New Jersey 07436 (973)845-6700 Gittleman Muhlstock & Chewcaskie Brian M. Chewcaskie, Esq. (Attorney ID No. 021201984) 2200 Fletcher Avenue Fort Lee, New Jersey 07024 (201)944-2300 Attorneys for Defendants SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY JACQUELINE ROSA, LAW DIVISION – HUDSON COUNTY Plaintiff, v. DOCKET NO.: HUD-L-607-18 BOROUGH OF LEONIA, et al., Civil Action Defendants. NOTICE OF MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF ORDER DATED AUGUST 30, 2018 GRANTING PLAINTIFF/INTERVENOR’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT STATE OF N.J. DEP’T OF TRANSPORTATION, Before: Peter F. Bariso, Jr., A.J.S.C. Plaintiff/Intervenor, Motion Date: October 12, 2018 v. BOROUGH OF LEONIA, N.J., Defendant. To: Philip J. Espinosa, Esq. Deputy Attorney General of New Jersey R.J. Hughes Justice Complex 25 Market Street P.O. Box 114 Trenton, New Jersey 08625 Attorney for Plaintiff/Intervenor State of New Jersey Department of Transportation 1 HUD-L-000607-18 09/20/2018 4:04:44 PM Pg 2 of 3 Trans ID: LCV20181638897 On Notice To: Jacqueline Rosa, Esq., Plaintiff Seigel Law Firm LLC 505 Goffle Road Ridgewood, New Jersey 07450 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on October 12, 2018 at 9:00 a.m. or as soon thereafter as counsel may be heard, Defendant Borough of Leonia (“the Borough”) will move for reconsideration of the Order dated August 30, 2018 granting summary judgment to Plaintiff/Intervenor State of New Jersey Department of Transportation. -

2013 Annual Report

COVERCOVERcover Garden State Preservation Trust Annual Report FISCAL YEAR 2013 Johnson Lake, Byram, Sussex County Joint project of the NJ Conservation Foundation Land Conservancy of New Jersey Byram and Office of Green Acres (Land Conservancy photo) Garden State Preservation Trust Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Report This is the Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for Fiscal Year 2013 from July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013. The core of the public-information mission of the Garden State Preservation Trust has been to document and illustrate achievements in conservation and preservation – with an emphasis on accomplishments at the municipal level. We measure this by acres preserved. But it is also importation to show grants for recreational development, historic site funding and the intact farms that have been protected. The bulk of the Annual Report focuses on all of this information. Of course, the statutory function of this Annual Report concerns GSPT financing, appropriations and agency operations. These are contained in the chapters which follow the Legislative District preservation tables. This is to be construed as the full annual report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the 2013 Fiscal Year in compliance with P.L. 1999 C.152 section 8C-15. It is also intended to be a comprehensive summary of required financial reporting from FY2000 through FY2013, providing a full accounting of Garden State Preservation Trust activities since July 1999. The principal author is Executive Director Ralph Siegel. A special debt is owed to Bryan Lofberg of the State Agriculture Development Committee for years of patience, thorough assistance and faithful friendship. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2018 69

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2018 69 The Hudson County Court House and Hugh Roberts: A Building and Architect in Perspective By Randall Gabrielan DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v4i2.128 Hugh Roberts, the architect of the Hudson County Court House, has had his career identified in totality with this building that brought him fame for its artistic stature and shame for his envelopment in the graft scandal that followed its 1910 opening. History has been kinder to him than were his contemporaries. Accusations against him are now considered to have been unjustified, but the imbroglio derailed his practice. The court house and much of the Roberts oeuvre originated through the influence of and his relationships with the politically powerful. Examination of the court house project, Roberts’ other work and the law suit place both architect and building in sharper focus. Early Life and Influences Hugh Roberts, born in Brooklyn in 1867 and educated at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, was established in Jersey City at least by 1893 (when he began appearing in city directories). He had early New York addresses at 287 Fourth Avenue and 1123 Broadway, but they were likely offices of convenience (which numerous New Jersey architects maintained). An 1899 guide to New York architects claims, “He is at his office very little. Main office is at 76 Montgomery Photograph of Roberts 1 from Meeker, Ellis R., The Street, Jersey City,” where he had been established by 1896. Roberts State of New Jersey , 1906. 1 Dennis Steadman Francis, Architects in Practice, New York City, 1840-1900 (New York: Committee for the Preservation of Architectural Records, 1979). -

FISCAL YEAR 2012 with District-By-District Tables on Park Development Grants

COVERCOVERcover Garden State Preservation Trust Annual Report FISCAL YEAR 2012 With district-by-district tables on park development grants Essex County Riverfront Park, Newark Garden State Preservation Trust Fiscal Year 2012 Annual Report This is the Annual Report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the Fiscal Year 2012 from July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2012. It has always been the goal and mission of the Garden State Preservation Trust to place preservation first. This has been traditionally measured in the number of acres preserved as parks, nature refuges and farmland. But substantial share of Garden State Preservation Trust funding has gone to recreational development, an elusive metric because the allocations of dollars are not easily sorted into specific parks or projects. In Fiscal Year 2012 this reporting was accomplished and is included in this annual report for the first time. This is to be construed as the full annual report of the Garden State Preservation Trust for the 2012 Fiscal Year in compliance with P.L. 1999 C.152 section 8C-15. It is also intended to be a comprehensive summary of required financial reporting from FY2000 through FY2012 – a “one-stop” document of the career of the Garden State Preservation Trust since July 1999. The principal author is Executive Director Ralph Siegel. Special thanks are owed to Bryan Lofberg of the State Agriculture Development Committee, Joseph Lombardo of the NJ Treasury Office of Management & Budget and Eric Knudsen of the NJDEP Office of Green Acres for their crucial assistance. Please note that any errors are the fault of the author. -

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources Tier 1 Final EIS Volume 1 NEC FUTURE Appendix EE.09 - Cultural Resources: Data Geography Affected Environment Environmental Consequences Context Area NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE State County Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line DC District of Columbia 10 21 0 10 21 0 0 3 0 0 4 0 49 249 0 54 248 0 MD Prince George's County 0 7 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 23 0 1 23 0 MD Anne Arundel County 0 3 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0 0 8 0 MD Howard County 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 1 3 0 MD Baltimore County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 10 0 MD Baltimore City 3 44 0 3 46 0 0 1 0 0 5 0 25 212 0 26 213 0 MD Harford County 0 5 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 12 0 1 15 0 MD Cecil County 0 6 2 0 8 2 0 0 2 0 1 2 0 11 2 0 11 2 DE New Castle County 3 64 2 3 67 2 0 2 1 0 5 2 3 187 1 4 186 2 PA Delaware County 0 4 0 1 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 18 0 1 18 0 PA Philadelphia County 9 85 1 10 87 1 0 2 1 3 4 1 57 368 1 57 370 1 PA Bucks County 3 8 1 3 8 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 15 1 3 15 1 NJ Burlington County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 17 0 1 17 0 NJ Mercer County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 0 2 0 0 2 5 40 1 6 40 1 NJ Middlesex County 1 20 2 1 20 2 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 42 2 1 42 2 NJ Somerset County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 4 0 NJ Union County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 1 1 0 2 1 2 17 1 2 17 1 NJ Essex County 1 24 1 1 26 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 65 1 1 65 1 NJ Hudson County