King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church and State Relations in the Constitution of Malta

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Analecta Cracoviensia Polonia Sacra 22 (2018) nr 2 (51) ∙ s. 175–199 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/ps.2505 Kevin Aquilina1 University of Malta Church and State Relations in the Constitution of Malta The Constitution of Malta (hereinafter ‘the Constitution’), the highest law of the land, regulates the relationship between the Catholic Church and the State of Malta. This is because there are a number of provisions in the Constitution which refer to the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church and to religion as discussed below. First, there is the provision which includes the Catholic religion amongst the state’s symbols. Then there is the provision which regulates the teaching of religion in state schools. Finally, there are provisions in the Constitution which deal with freedom of conscience and worship. It is understandable that the Constitution contains such provisions on the Church and on religion because Malta is a Catholic country. However, this paper recounts, from a historic and le- gal perspective, that recent secularisation trends are eroding the special status that the Church and the Catholic religion have enjoyed in Maltese society and, the more time passes, it appears that Malta is moving in the footsteps of Western Europe of losing its religious character to substi- tute it with a more secular outlook. This is evident from the legislation surveyed in this paper which tends to inspire itself less for the making 1 Professor Kevin Aquilina is the Dean of the Faculty of Laws at the University of Malta. -

THE MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 161 April 2017

THE MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 161 April 2017 Mirror By Nicola Agius © Provided by Trinity Mirror Plc Credits: B&Q Britain's biggest family The Radfords are set to welcome a new addition to their brood - as mum Sue Radford is pregnant with her 20th child. Sue - whose family have their own reality show, 19 Kids And Counting - confirmed the happy news today by sharing a picture of a scan on social media. She then shared a picture of a chalkboard revealing the latest arrival is due in September 2017. She was immediately inundated with messages from friends and fans congratulating her and Noel for 'evening out' their number of offspring. "Wow congratulations to you all.. hats off to ya your amazing xx," said one admiring follower. "Massive congratulations Sue Noel and your amazing brood! Hope all goes well xx," wrote another. It comes after the family opened up about their Christmas plans on This Morning in December 2016. Noel and Sue, from Heysham, Lancashire, welcomed their 19th baby Phoebe in July last year. They are also parents to Chris, 27, Sophie, 22, Chloe, 21, Jack, 19, Daniel, 17, Luke, 15, Millie, 14, Katie, 13, James, 12, Ellie, 11, Aimee, 10, Josh, 9, Max, 7, Tilly, 6, Oscar 4, Casper, 3 and toddler Hallie. Provided by Trinity Mirror Plc Credits: Manchester Evening News Syndication However, Noel and Sue - who do not claim any extra state benefits aside from the regular child benefit - didn't have a table quite big enough for their Christmas dinner plans. Explaining ahead of the festive season how it will work, Noel said: "It's going to be like a conveyor belt. -

Monumenti U Busti Fil-Gżejjer Maltin

monumenti u busti fil-gżejjer Maltin ANTON CAMILLERI WERREJ Abbrevjazzjonijiet 24 Ħajr 25 Daħla 27 Kelmet l-awtur 29 Introduzzjoni 31 MALTA 35 Ħ’Attard 36 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 36 Monument lill-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 37 Monument b’tifkira tal-Union Maltija tal-Infermiera u l-Qwiebel 38 Monument lin-nanniet 39 Bust lil Pierre Muscat 40 Bust lill-Mastru Karm Debono 41 Busti lir-Re Ġorġ V u r-Re Ġorġ VI 41 Bust lill-Prinċep Ġorġ – Duka ta’ Kent 42 Bust lil San Ġorġ Preca 43 Bust lil Madre Tereża 43 Busti lill-Presidenti tar-Repubblika 44 Il-Balluta 46 Bust lill-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 46 Bust lill-Madonna tal-Karmnu 47 Ħal Balzan 48 Bust lil Dun Ġwann Zammit Hammet 48 Bust lil Gabriel Caruana 49 Il-Birgu 50 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 50 Monument tad-900 sena mit-twaqqif tal-knisja ta’ San Lawrenz parroċċa 51 Monument tal-1750 sena mill-martirju ta’ San Lawrenz 52 Monument tal-Assedju l-Kbir tal-1565 53 Monument b’tifkira ta’ Jum il-Ħelsien 54 Monument LILl-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 55 Bust lil Sir Paul Boffa 56 Bust lil Nestu Laiviera 57 Bust lill-Gran Mastru Fra Nicola Cotoner 58 Bust lil Mons. Dun Ġużepp Caruana 59 7 Birkirkara 61 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 61 Monument tal-mitt sena mill-inkurunazzjoni tal-kwadru tal-Madonna tal-Ħerba 62 Monument lil Sir Anthony Mamo 63 Monument lill-vittmi Karkariżi tal-logħob tan-nar 64 Bust lill-Kavallier Ċensu Borg ‘Brared’ 65 Busti lill-Papa Urbanu VIII u l-Papa Piju XII 65 Busti lil Ġużeppi Briffa u Carmelo Brincat 67 Bust lil Karin Grech 68 Bust lill-Maġġur Anthony Aquilina 69 Bust lill-Mro Kavallier Ġużeppi Busuttil 70 Bust lit-Tabib Robert Farrugia Randon 71 Bust lis-Surmast Raffaele Ricci 71 Bust lis-Surmast Tommaso Galea 72 Bust lil John A. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 305 February 2020 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 305 February 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 305 February 2020 Published on Wednesday 22 January 2020 Director of Funding and Strategy, Arts Council Malta, Mary Ann Cauchi, glances at the Create2020 Strategy and what’s in store to continue achieving high levels of excellence and develop Malta’s creative sector.The creative vision of the Create2020 Strategy implemented through nine strategic tools which included: • funding programmes supporting various projects in the creative industries; • creative brokerage serving as the first point of reference for difficulties and assistance; • educational and training initiatives focusing on artistic practice requirements; • a community cultural exchange developing a rich and varied artistic and innovative life; • nurturing of business development; • promotion of the development of a sustainable creative economy; • internationalisation placing Malta’s international cultural profile on global platforms beyond Europe; • research providing a stronger knowledge base; • communication allowing knowledge transfer with various stakeholders. Throughout this past year in my role as Director of Funding and Strategy, it has been a great pleasure meeting a diverse range of people and understanding their needs through various processes such as focus groups, one-to-one or group meetings, workshops, networking or information sessions. In fact, gaining valuable first-hand information straight from the source is one of my favourite elements of the job. 2020 is a pivotal year for the creative sector and for Arts Council Malta, both internally and externally, an evaluation of the progress covered to date and consultation for the next strategy 2021-2025 will take place. It is forecasted that the new strategy will continue to place the arts and creativity at the heart of Malta’s future and making sure to engage a wider audience. -

Feature Sunday 04 September 2005 Maltatoday 07

07 10/7/05 12:16 Page 1 feature Sunday 04 September 2005 maltatoday 07 The two protagonists: Archbishop Michael Gonzi (L) and a young Dom Mintoff (R) addressing a mass meeting outside a parish church. Inset (L) Church supporters and women from the MUSEUM hissing at a Labour gathering in 1961, and (R) the Hal- Ghaxaq MLP club during the 1962 election The unholy war The notorious ‘interdett’ is part of a tragic episode in Maltese history when the island was split between the competing aspirations of the Malta Labour Party and the Catholic Church for the future of the island beyond colonialism. IN JANUARY 1961, the diocesan com- would be recommended to the village The churchÕs decree fragmented society on bikini-clad tourists, for fear of com- mission issued a circular which was read contractor by the parish priest. The to such an extent, that a parallel society promising MaltaÕs reputation as a in all churches condemning the MLPÕs priest was the village ÔpsychologistÕ. was created. Alternatives to mainstream tourist destination. affiliation with the Socialist International In a decade where progressive cultural activities were organised. Labourites had In the parallel, Labour society howev- and the Afro-Asian Peoples Solidarity revolutions were taking place across all their own carnival of flowers, their own er, Labourite girls felt protected to freely Organisation. In a bid to wield its power western societies, the regressive actions snooker tournaments, and their own put on their bikinis during beach parties, over the god fearing masses, it declared a taken by the Maltese church remain a Labourite brigade as opposed to the an acceptable practice in the world of sin the reading of Labour newspapers historical irony. -

Programm Tal-Festa Titulari Santa Marija Mqabba 2009

Les Etoiles d’Or du Jumelage - 1998 Rebbie˙a tal-Ewwel Festival Internazzjonali tan-Nar ta’ Malta - 2006 Rebbie˙a Assoluti tal-Kampjonat Mondjali tan-Nar Caput Lucis, Ruma - 2007 WWerrejerrej Kumitat EΩekuttiv 2009 .........................................................................................Pa©na 3 Impenn u preparazzjoni - Messa©© tal-President tas-Soçjetà ................................ Pa©na 5 Lokalità Sostenibbli anke bil-festi tag˙na ... sabiex fl imkien ng˙ixu a˙jar – Messa©© tas-Sindku tal-Imqabba ........................ .........................................Pa©na 7 Bord Editorjali Santa Marija fost l-ikbar festi li g˙andha l-Knisja BRIFFA Carmel ELLUL Carmel – Rifl essjoni mill-Kappillan tal-Parroçça …... ...............................................Pa©na 11 SCIBERRAS Antoine Lejn il-100 sena mit-twaqqif tas-Soçjetà SPITERI Christopher – Messa©© mis-Segretarju tas-Soçjetà ........................................................... Pa©na 13 Artikolisti Flimkien niççelebraw Festa o˙ra kbira - Appell mill-Kaxxier ............................ Pa©na 15 AGIUS Mro. David Ìita Indimentikabbli ............................................................................................Pa©na 16 BIANCHI Chev. Carmel Festa Titulari u Universali – Rifl essjonijiet mid-Direttur Spiritwali ................... Pa©na 17 BRIFFA Carmel CAMILLERI Benjamin Sena s˙i˙a ta’ ˙idma kontinwa fuq l-armar tal-Festa CAMILLERI Gilbert – Appell mill-G˙aqda tal-Armar............... .....................................................Pa©na 19 CAMILLERI -

Birgu Promontory Their Knowledge and Experience to Successive Generations of Workers

spread along the coast and some of them could also be seen reaching out into the sea. From the places of worship built in this area, one may conclude that Christians, both of the Byzantine and Roman rites, Hebrews and, even Muslims, although no tangible proof of any mosque exists, all practiced their beliefs in this area. The shores beneath the Castle are the cradle of the technology and craftsmanship of the Island. As early as 1374, in the vicinity of Fort St.Angelo, there was already a well-established dockyard where galleys were built or repaired. In 1501, a bigger dockyard was built. Later, the Order built another one which was considered as the best in the Mediterranean. Eventually, many craftsmen and tradesmen passed on Aerial view of Birgu promontory their knowledge and experience to successive generations of workers. So this city has always been renowned for its craftsmen and tradesmen. Introduction Those who lacked skills earned their living as sailors on the various vessels which berthed alongside Birgu Wharf, later known as Galley Creek, where ships of all kind loaded or unloaded their wares to be sold Being experienced seafarers, the early settlers of these Islands became or bought along the shores of the Marina. This activity reached its climax immediately aware that the coast on the Western side of the promontory on in 1127 when Malta was annexed to the Kingdom of Sicily. which the city of Birgu was later built, offered shelter and security. They The importance which this part of the coast enjoyed was confi rmed realized that at the same time, if they were to be attacked by newcomers, when a castle was built at the end of the promontory. -

It-28 Ta' Lulju, 2021 7589 This Is a List of Complete Applications Received

It-28 ta’ Lulju, 2021 7589 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-13 ta’ Settembru, 2021. -

The Church School Saga (Part 1)

12 13 Feature maltatoday, SUNDAY, 25 APRIL 2010 maltatoday, SUNDAY, 25 APRIL 2010 Feature THE CHURCH SCHOOL SAGA ‘JEW B’XEJN, JEW XEJN’ (PART 1) In the first of a three-part feature, Gerald Fenech TIMELINE delves into the historical importance of church December 1981: The Labour Party wins the 1981 election with a majority of seats but a minority schools in Malta and the battle for their existence of votes. ‘Free education for all’ part of Labour’s in the 1980s that led to the Catholic Church-State manifesto. compromise December 1982: Legal Notice freezing Church School fees at 1982 levels published February 1983: The Holy See protests against the ‘20 points’ awarded to state school students June 1983: Publication of White Paper on Devolution of Church Property Acquired by Prescription July 1983: Archbishop Joseph Mercieca returns from Rome after meetings with Holy See officials. Insists that Church will not cede to government’s demands and will retain all legal rights September 1983: Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici becomes Minister of Education. Curia publishes 1982 accounts, showing losses of Lm190,000, but does not take into account immovable properties not used for ecclesiastical purposes and their The massive demonstration in support of Church schools Dingli Street, Sliema, 1984 income. PRIVATE education has always been a contentious issue er draconian measures, such as the freezing of compensa- October 1983: Church files case in Constitutional in Malta. In the eyes of some, it’s a sector that has been tion limits up to a maximum of Lm50,000 (€120,000) and Court to declare Devolution Act null. -

It-3 Ta' Ġunju, 2020 4485 This Is a List of Complete Applications

It-3 ta’ Ġunju, 2020 4485 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-03 ta’ Lulju, 2020. -

Gozo in the World and the World in Gozo

Gozo in the world and the world in Gozo The cultural impact of migration and return migration on an island community Raymond C. Xerri Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy Europe-Ausfralia Institute Victoria University of Technology 2002 CONTENTS Declaration iv Acknowledgements v Abstract ix INTRODUCTION 1 PARTI GOZO 1. Ferry Crossings 15 2. Gozitan Identity Under Construction 43 3. Double Crossings: Positioned Ethnography and Writing Gozo 77 Pictorial Essay I Imag(in)ing Gozo 94 PARTII GOZO IN THE WORLD 4. The Land at the Edge of the World 99 5. Making Dreams Work 123 6. Faith and Festa 148 7. Linguistic Menus 181 Pictorial Essay II Gozo-Melbourne Crossings 197 PART III THE WORLD IN GOZO 8. Bingo, Races and Bars 202 9. Making Money 221 10. Flags and Firecrackers 247 Pictorial Essay III Melbourne-Gozo Crossings 271 CONCLUSION 276 REFERENCES 280 APPENDICES 289 TABLES AND FIGURES Figure 1. Nassa tas-Sajd G^awdxija (Gozitan Fisherman's pot) 27 Figure 2. Village of Qala coat-of-arms 38 Figure 3. City of Rabat coat-of-arms 39 Figure 4. The Flag of Gozo 39 Table 1. 1915 Gozitan Passport Applications for Ausfraha Nos. 42-52 104 Table 2. City of Brimbank: Residents' Place of Birth 118 Table 3. Gozitan Organisations in Melbourne 153 11 Table 4. Gozitan Festas Celebrated in Melboume 160 APPENDICES Appendix 1. Basic Xerri-Buttigieg Family Tree Appendix 2. Xerri Buttigieg Marriages Appendix 3. Questionnaire/Interview Questions Appendix 4. Responses to Question : Why did so many Gozitans settle in Melboume? Appendix 5. -

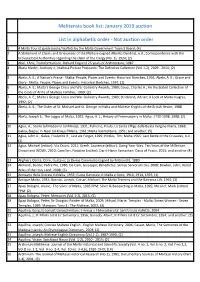

Melitensia Book List: January 2019 Auction List in Alphabetic Order

Melitensia book list: January 2019 auction List in alphabetic order - Not auction order 1 4 Malta Tourist guide books/ leaflets by the Malta Government Tourist Board; (4) 2 A Statement of Claims and Grievances of the Maltese (signed Alberto Dandria), n.d.; Correspondence with the Ecclesiastical Authorities regarding the claim of the Clergy (No. 3), 1924; (2) 3 Abel, Chris; Transformations: Richard England 25 years of Architecture; 1987 4 Abela Medici, Anthony J.; Maltese Picture Postcards: The Definitive Collection (Vol.1-2), 2009 - 2014; (2) 5 Abela, A. E.; A Nation's Praise - Malta: People, Places and Events: Historical Sketches, 1994; Abela, A. E.; Grace and Glory - Malta: People, Places and Events: Historical Sketches, 1997; (2) 6 Abela, A. E.; Malta's George Cross and War Gallantry Awards, 1989; Gauci, Charles A.; An Illustrated Collection of the Coats of Arms of Maltese Families, 1989; (2) 7 Abela, A. E.; Malta's George Cross and War Gallantry Awards, 1989; Strickland, Adrian; A Look at Malta Insignia, 1992; (2) 8 Abela, A. E.; The Order of St. Michael and St. George in Malta and Maltese Knights of the British Realm, 1988 9 Abela, Joseph S.; The Loggia of Malta, 1992; Agius, A. J.; History of Freemasonry in Malta: 1730-1998, 1998; (2) 10 Agius, A.; Storia tal Madonna tal Minsija, 1931; Pullicino, Paulo; La Santa Effige della Beata Vergine Maria, 1868; Galea, Biagio; In-Nisel tal-Knisja f'Malta, 1961; Malta Karmelitana, 1951; and another; (5) 11 Agius, John A.; Galea, Frederick R.; Lest we Forget, 1999; Pickles, Tim; Malta 1565: