The Alleys of Birgu — Exploring Malta’S Victorious City —

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NOTICE to MARINERS No 105 of 2019

PORTS AND YACHTING DIRECTORATE LOCAL NOTICE TO MARINERS No 105 of 2019 Our Ref: TM/PYD/132/89 19 August 2019 Filming outside Marsamxett Harbour and inside the Grand harbour, Valletta - The story of my wife The Ports and Yachting Directorate, Transport Malta notifies mariners and operators of vessels, that filming activities will take place outside Marsamxett Harbour at point A (as indicated on attached chart) and at Boiler Wharf inside the Grand Harbour, Valletta. The filming will take place on Friday 23 rd August 2019 and Saturday 24 th August 2019. The filming involves the use of the vessel UTEC Surveyor as a prop and she will be towed by the tug boats Sea Wolf and Sea Jaguar whenever it has to be moved. Friday 23 rd August 2019: 0600 hours UTEC Surveyor will be towed from Cassar Shipyard to be moored at Boiler Wharf. 0900 hours UTEC Surveyor towed from Boiler Wharf to outside Marsamxett Harbour where filming onboard the vessel will commence. In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed again to Boiler Wharf where filming will take place from arrival to midnight. Saturday 24 th August 2019: 0900 hours UTEC Surveyor towed from Boiler Wharf to outside Marsamxett Harbour where filming onboard the vessel will commence. In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed again to Boiler Wharf where filming will take place from arrival to midnight. Monday 26 th August 2019: In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed back to Cassar Shipyard. Mariners are to note the above and give a wide berth while the UTEC Surveyor is being towed and while it is anchored at point A (as indicated on attached chart). -

Annual Report 2007-2008

Annual Report 2007-2008 Annual Report 2007-2008 In accordance with the provisions of the Cultural Heritage Act 2002, the Board of Directors of Heritage Malta herewith submits the Annual Report & Accounts for the fifteen months ended 31 st December 2008. It is to be noted that the financial year–end of the Agency was moved to the 31 st of December (previously 30 th September) so as to coincide with the accounting year-end of other Government agencies . i Table of Contents Heritage Malta Mission Statement Pg. 1 Chairman’s Statement . Pg. 2 CEO’s Statement Pg. 4 Board of Directors and Management Team Pg. 5 Capital, Rehabilitation and Maintenance Works Pg. 7 Interpretation, Events and Exhibitions Pg. 17 Research, Conservation and Collections Pg. 30 The Institute for Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage Pg. 48 Conservation Division Pg. 53 Appendices I List of Acquisitions Pg. 63 II Heritage Malta List of Exhibitions October 2007 – December 2008 Pg. 91 III Visitor Statistics Pg. 96 Heritage Malta Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements Heritage Malta Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements Pg. 100 ii List of Abbreviations AFM Armed Forces of Malta AMMM Association of Mediterranean Maritime Museums CHIMS Cultural Heritage Information Management System CMA Collections Management System EAFRD European Agricultural Regional Development Funds ERDF European Regional Development Funds EU European Union HM Heritage Malta ICMCH Institute of Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage, Bighi MCAST Malta College -

Introduction – Grand Harbour Marina

introduction – grand harbour marina Grand Harbour Marina offers a stunning base in historic Vittoriosa, Today, the harbour is just as sought-after by some of the finest yachts Malta, at the very heart of the Mediterranean. The marina lies on in the world. Superbly serviced, well sheltered and with spectacular the east coast of Malta within one of the largest natural harbours in views of the historic three cities and the capital, Grand Harbour is the world. It is favourably sheltered with deep water and immediate a perfect location in the middle of the Mediterranean. access to the waterfront, restaurants, bars and casino. With berths for yachts up to 100m (325ft) in length, the marina offers The site of the marina has an illustrious past. It was originally used all the world-class facilities you would expect from a company with by the Knights of St John, who arrived in Malta in 1530 after being the maritime heritage of Camper & Nicholsons. exiled by the Ottomans from their home in Rhodes. The Galley’s The waters around the island are perfect for a wide range of activities, Creek, as it was then known, was used by the Knights as a safe including yacht cruising and racing, water-skiing, scuba diving and haven for their fleet of galleons. sports-fishing. Ashore, amid an environment of outstanding natural In the 1800s this same harbour was re-named Dockyard Creek by the beauty, Malta offers a cosmopolitan selection of first-class hotels, British Colonial Government and was subsequently used as the home restaurants, bars and spas, as well as sports pursuits such as port of the British Mediterranean Fleet. -

Public List of Active Licence Holders Tel No Sector / Classification

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL THE RESIDENCE ST JULIANS 21360031 Two Star Fax No TRIQ L. APAP 21374114 HCEB Ref AH/0137 Contrib Ref 02-0044 ST. JULIAN'S STJ 3325 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 124 Web-Site Address www.theresidencestjulians.com Apartments 48 HOTEL UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE 21430360/21436168 Two Star Fax No TRIQ ROBERT MIFSUD BONNICI HCEB Ref AH/0145 Contrib Ref LIJA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 66 Web-Site Address www.universityresidence.com Apartments 33 HOTEL HULI CRT APARTHOTEL 21572200/21583741 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IN-NAKKRI HCEB Ref AH/0214 QAWRA Contrib Ref 02-0069 ST.PAUL'S BAY No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 56 Web-Site Address Apartments 19 HOTEL FOR REST APARTHOTEL 21575773 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IL-HGEJJEG HCEB Ref AH/0370 BUGIBBA Contrib Ref ST.PAUL'S BAY SPB 2825 No Of Bedrooms 4 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 40 Web-Site Address Apartments 16 HOTEL PEBBLES BOUTIQUE APARTHOTEL SLIEMA 21311889/21335975 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IX-XATT 21316907 HCEB Ref AH/0395 Contrib Ref 02-0068 SLIEMA SLM 1022 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 92 Web-Site Address www.pebbleshotelmalta.com Apartments 26 Report Date: 30/08/2019 1-21PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL ALBORADA APARTHOTEL (BED & BREAKFAST) 21334619/21334563 Two Star 28 Fax No TRIQ IL-KBIRA -

FRENCH in MALTA Official Programme for Re-Enactments

220TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FRENCH IN MALTA Official Programme for Re-enactments - www.hrgm.org Day Time Event Place Name Description Location Tue, 05 June 10:30 Battle Floriana Maltese sortie against the French and are ambushed Portes de Bombes, Floriana - adjacent woodland 12:30 Parade Valletta Maltese & French forces march into the city Starts at City Gate, ends Palace Square 19:00 Parade Mosta French march through the town ending with short display Starts at Speranza Chapel 19:00 Parade Gharghur Call to arms against the French Main square 20:00 Activities Naxxar Re-enactors enjoy an eve of food, drink, music, songs, & dance Main square Wed, 06 June 16:30 Battle Mistra Bay French landing at Mistra Bay and fight their way to advance Starts at Mistra end at Selmun 20:30 Activities Mellieha Re-enactors enjoy an eve of food, drink, music, songs, & dance Main square Thu, 07 June 10:00 Open Day Birgu From morning till late night - Army garrison life Fort St Angelo 17:15 Parade Bormla Maltese Army short ceremony followed by march to Birgu Next to Rialto Theatre 17:30 Parade Birgu French Army marches to Birgu main square Starts at Fort St Angelo, ends in Birgu main square 17:45 Ceremony Birgu Maltese & French Armies salute eachother; march to St Angelo Birgu main square Fri, 08 June 16:30 Battle Chadwick Lakes French attacked near Chadwick Lakes on the way to Mdina Chadwick Lakes - extended area 18:00 March Mtarfa Maltese start retreat up to Mtarfa with French in pursuit Chadwick Lakes in the vicinity of Mtarfa 18:45 Battle Mtarfa Fighting continues at Mtarfa Around the Clock Tower area 20:00 Battle Rabat Fighting resumes at Rabat. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/09612025.2019.1702789 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Harris, A. G. (2019). ‘Lady Doctor among the “Called”’: Dr Letitia Fairfield and Catholic medico-legal activism beyond the bar. Women's History Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2019.1702789 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

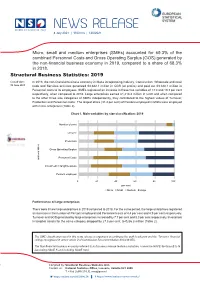

Structural Business Statistics: 2019

8 July 2021 | 1100 hrs | 120/2021 Micro, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) accounted for 69.3% of the combined Personnel Costs and Gross Operating Surplus (GOS) generated by the non-financial business economy in 2019, compared to a share of 68.3% in 2018. Structural Business Statistics: 2019 Cut-off date: In 2019, the non-financial business economy in Malta incorporating Industry, Construction, Wholesale and retail 30 June 2021 trade and Services activities generated €3,882.1 million in GOS (or profits) and paid out €3,328.1 million in Personnel costs to its employees. SMEs registered an increase in these two variables of 13.0 and 10.3 per cent respectively, when compared to 2018. Large enterprises earned €1,218.3 million in GOS and when compared to the other three size categories of SMEs independently, they contributed to the highest values of Turnover, Production and Personnel costs. The largest share (31.4 per cent) of Persons employed in Malta were employed with micro enterprises (Table 2). Chart 1. Main variables by size classification: 2019 Number of units Turnover Production Gross Operating Surplus Personnel Costs main variables Investment in tangible assets Persons employed 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% per cent Micro Small Medium Large Performance of large enterprises There were 8 new large enterprises in 2019 compared to 2018. For the same period, the large enterprises registered an increase in the number of Persons employed and Personnel costs of 4.4 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively. Turnover and GOS generated by large enterprises increased by 7.7 per cent and 8.3 per cent respectively. -

PDF Download Malta, 1565

MALTA, 1565: LAST BATTLE OF THE CRUSADES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Pickles,Christa Hook,David Chandler | 96 pages | 15 Jan 1998 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855326033 | English | Osprey, United Kingdom Malta, 1565: Last Battle of the Crusades PDF Book Yet the defenders held out, all the while waiting for news of the arrival of a relief force promised by Philip II of Spain. After arriving in May, Dragut set up new batteries to imperil the ferry lifeline. Qwestbooks Philadelphia, PA, U. Both were advised by the yearold Dragut, the most famous pirate of his age and a highly skilled commander. Elmo, allowing Piyale to anchor his fleet in Marsamxett, the siege of Fort St. From the Publisher : Highly visual guides to history's greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics, and experiences of the opposing forces throughout each campaign, and concluding with a guide to the battlefields today. Meanwhile, the Spaniards continued to prey on Turkish shipping. Tim Pickles describes how despite constant pounding by the massive Turkish guns and heavy casualties, the Knights managed to hold out. Michael across a floating bridge, with the result that Malta was saved for the day. Michael, first with the help of a manta similar to a Testudo formation , a small siege engine covered with shields, then by use of a full-blown siege tower. To cart. In a nutshell: The siege of Malta The four-month Siege of Malta was one of the bitterest conflicts of the 16th century. Customer service is our top priority!. Byzantium at War. Tim Pickles' account of the siege is extremely interesting and readable - an excellent book. -

The Three Cities

18 – The Three Cities The Three Cities are Vittoriosa/Birgu, Cospicua/Bormla and Senglea/L’Isla. Most of the Three Cities was badly bombed, much of its three parts destroyed, during the Second World War. Some inkling of what the area went through is contained in Chapter 15. Much earlier, it had been bombarded during the Great Siege of 1565, as described in Chapter 5, which also tells how Birgu grew from a village to the vibrant city of the Order of the Knights of St John following their arrival in 1530. You cannot travel to the other side of the Grand Harbour without bearing those events in mind. And yet, almost miraculously, the Three Cities have been given a new lease of life, partly due to European Union funding. You would really be missing out not to go. Most of the sites concerning women are in Vittoriosa/Birgu. From the Upper Barracca Gardens of Valletta you get a marvellous view of the Three Cities, and I think the nicest way to get there is to take the lift down from the corner of the gardens to the waterfront and cross the road to the old Customs House behind which is the landing place for the regular passenger ferry which carries you across the Grand Harbour. Ferries go at a quarter to and a quarter past the hour, and return on the hour and the half hour. That is the way we went. Guide books suggest how you make the journey by car or bus. If you are taking the south tour on the Hop-On Hop-Off bus, you could hop off at the Vittoriosa waterfront (and then hop on a later one). -

Measuring and Modelling Demographic Trends in Malta: Implications for Ageing Policy

International Journal on Ageing in Developing Countries, 2019, 4 (2): 78-90 Measuring and Modelling Demographic Trends in Malta: Implications for Ageing Policy Marvin Formosa1 Abstract. Malta’s population experienced a sharp ageing transition due to increasing and decreasing levels of life expectancy and fertility rates respectively. This article reviews demographic changes relating to population ageing that took place in Malta, and future population projections which anticipate even higher numbers and percentages of older persons. At end of 2017, 18.8% of the total population, or 89,517 persons, were aged 65-plus. The largest share is made up of women, with 53.4% of the total. The sex ratios for cohorts aged 65-plus and 80-plus in 2013 numbered 83 and 60 respectively. Population projections indicate clearly that Malta will be one of the fastest ageing countries in the European Union. the (Maltese) percentage of children (0-14) of the total population is projected to increase slightly from 14.5% to 15.4% (+0.9%), whilst the working-age population (15-64) will experience dramatic decrease, from 68 to 56.1% (-11.9%). On the other hand, the older population segment will incur extraordinary increases. The 65-plus/80-plus population will reach 28.5%/10.5% of the total population in 2060, from 17.5%/3.8% in 2013 (+11.0/6.7%). The ageing-related challenges that the Maltese government that is currently facing traverse three key overlapping areas of policy boundaries and include the labour market, health care, and long-term care. There will also be policy issues which, if not immediate, will certainly need to be addressed in the foreseeable future. -

Medieval Mdina 2014.Pdf

I Fanciulli e la Corte di Olnano This group was formed in 2002 in the Republic of San Marino. The original name was I Fanciulli di Olnano meaning the young children of Olnano, as the aim of the group was to explain history visually to children. Since then the group has developed Dolceria Appettitosa into a historical re-enactment group with adults Main Street and children, including various thematic sections Rabat within its ranks specializing in Dance, Singing, Tel: (00356) 21 451042 Embroidery, Medieval kitchen and other artisan skills. Detailed armour of some of the members of the group highlights the military aspects of Medieval times. Anakron Living History This group of enthusiasts dedicate their time to the re-enactment of the Medieval way of life by authentically emulating the daily aspects of the period such as socialising, combat practice and playing of Medieval instruments. The Medieval Tavern was the main centre of recreational, entertainment, gambling and where hearty home cooked meal was always to be found. Fabio Zaganelli The show is called “Lost in the Middle Ages”. Here Fabio acts as Fabius the Court Jester and beloved fool of the people. A playful saltimbanco and histrionic character, he creates fun and involves onlookers of all ages, Fabio never fails to amaze his audiences with high level circus skills and comedy acts, improvised dialogue plays and rhymes, poetry and rigmaroles. Fabio is an able juggler, acrobat, fakir and the way he plays with fi re makes him a real showman. BIBITA Bibita the Maltese minstrel band made their public Cafe’ Bistro Wine Bar debut at last year’s Medieval Festival. -

The Origin of the Name of Gozo.Pdf

The Origin of the Name of Gozo Horatio CAESAR ROGER VELLA The Name of Gozo paper will show, Gozo is an ancient variant of Gaudos from which it is derived, as much as Għawdex is. “Do you come from Għawdex?” is a question that The irony is that Gozo, Għawdex and Gaudos did sounds as discordant as the other one, “Intom minn not originally belong to us, as I explained in other Gozo?”. To one not conversant with the Greek origin publications of mine.1 of the names of Gozo, such questions sound like being uttered by Maltese trying to speak English, and Gaudos is the Greek name of a small island on the mix Maltese with English or, the other way round, south-western side of Crete, with its smaller sister like knowledgeable tourists trying to speak Maltese island of Gaudapula. Cretan Gaudos is half the size and, to our mind, mix it with “English”. This paper of our island of Gozo, roughly at 24˚ longitude and will show that none is the case. 35˚ latitude (1˚ southern than our Gozo), and less than 30 miles from Crete. We, in fact, can use “Għawdex” liberally when speaking in English; likewise, we can use the name The pronunciation of Cretan Gaudos from Byzantine of “Gozo” when speaking in Maltese, for, as this times has been not Gaudos, but Gavdos, for since those times, the Greeks developed the pronunciation of the diphthong au as “av”, as in thauma, pronounced as “thavma”, meaning “miracle”. Similarly, eu is pronounced as “ev” as in Zeus pronounced as “Zevs”, the chief god of the Greek pantheon.