Myanmar Update December 2019 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix – D Model Villages with Rice Husk Gas Engine

APPENDIX – D MODEL VILLAGES WITH RICE HUSK GAS ENGINE APPENDIX D-1 Project Examples 1 (1/3) Development Plan Appendix D-1 Project Examples 1: Rice Husk Gas Engine Electrification in Younetalin Village Plans were prepared to electrify villages with rice husk gas engine in Ayeyarwaddi Division headed by Area Commander. Younetalin Village was the first to be electrified in accordance with the plans. The scheme at Younetalin village was completed quite quickly. It was conceived in January 2001 and the committee was formed then. The scheme commenced operation on 15 2001 April and therefore took barely 3 months to arrange the funding and building. The project feature is as follows (as of Nov 2002): Nippon Koei / IEEJ The Study on Introduction of Renewable Energies Volume 5 in Rural Areas in Myanmar Development Plans APPENDIX D-1 Project Examples 1 (2/3) Basic Village Feature Household 1,100 households Industry and product 6 rice mills, BCS, Video/Karaoke Shops Paddy (Cultivation field is 250 ares), fruits processing, rice noodle processing) Public facilities Primary school, monastery, state high school, etc. Project Cost and Fund Capital cost K9,600,000 (K580,000 for engine and generator, K3,800,000 for distribution lines) Collection of fund From K20,000 up to K40,000 was collected according to the financial condition of each house. Difference between the amount raised by the villagers and the capital cost of was K4,000,000. It was covered by loan from the Area Commander of the Division with 2 % interest per month. Unit and Fuel Spec of unit Engine :140 hp, Hino 12 cylinder diesel engine Generator : 135 kVA Model : RH-14 Rice husk ¾ 12 baskets per hour is consumed consumption ¾ 6 rice mills powered by diesel generator. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

No. 19 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter December 1992

This NEWSLETTER is edited by Scott Bamber and published in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies; printed at Central Printery; the masthead is by Susan Wigham of Graphic Design (all of The Australian National University). The logo is from a water colour, 'Tai women fishing' by Kang Huo Material in this NEWSLETTER may be freely reproduced with due acknowledgement. Correspondence is welcome and contributions will be given sympathetic consideration. (All correspondence to The Editor, Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia.) Contents Seminar papers Burma's borders seminar The frontiers of 'Burma' Karen and conflict resolution Cross border trade Burmese refugees in Bangladesh Environment: degradation & conservation Trade, drugs and aids in Shan State Letters Books and publications Tai minorities in China Ethnic situation in China Contemporary Developments on Burma's Borders (Report on a seminar held at The Australian National University, 21 November 1992) This issue of the Newsletter is largely devoted to the papers delivered at the seminar. The attendance included both academics with an interest in Burma1 and Southeast Asia and members of the public, particularly representing the Burmese community in Canberra and Sydney. We have reason to believe that the exchange of ideas was mutually profitable. Many of the Burmese who attended are members of the Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in Burma and there was open and healthy discussion between those who held that the only issue of substance was the defeat of SLORC and those who attempted to analyze contemporary developments (some of which are working to the benefit of SLORC) and consequences for the future. -

Burma's Northern Shan State and Prospects for Peace

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBRIEF234 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip September 2017 DAVID SCOTT MATHIESON Burma’s Northern Shan State Email: [email protected] and Prospects for Peace Summary • Increased armed conflict between the Burmese Army and several ethnic armed organizations in northern Shan State threaten the nationwide peace process. • Thousands of civilians have been displaced, human rights violations have been perpetrated by all parties, and humanitarian assistance is being increasingly blocked by Burmese security forces. • Illicit economic activity—including extensive opium and heroin production as well as transport of amphetamine stimulants to China and to other parts of Burma—has helped fuel the conflict. • The role of China as interlocutor between the government, the military, and armed actors in the north has increased markedly in recent months. • Reconciliation will require diverse advocacy approaches on the part of international actors toward the civilian government, the Tatmadaw, ethnic armed groups, and civil society. To facili- tate a genuinely inclusive peace process, all parties need to be encouraged to expand dialogue and approach talks without precondition. Even as Burma has “transitioned from decades Introduction of civil war and military rule Even as Burma has transitioned—beginning in late 2010—from decades of civil war and military to greater democracy, long- rule to greater democracy, long-standing and widespread armed conflict has resumed between several ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw). Early in standing and widespread 2011, a 1994 ceasefire agreement broke down as relations deterioriated in the wake of the National armed conflict has resumed.” League for Democracy government’s refusal to permit Kachin political parties to participate in the elections that ended the era of military rule in the country. -

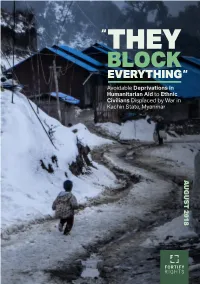

They Block Everything

Cover: Border Post 6 camp for displaced “ civilians near the China border in Myanmar’s Kachin State. Myanmar government restrictions on humanitarian aid have resulted in shortages of blankets, clothing, THEY bedding, and other essential items, making harsh winters unnecessarily difficult for displaced civilians. ©James Higgins / Partners Relief and BLOCK Development, February 2016 EVERYTHING“ Avoidable Deprivations in Humanitarian Aid to Ethnic Civilians Displaced by War in Kachin State, Myanmar Fortify Rights works to ensure human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage people with power on solutions, and strengthen the work of human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence-based research, the power of strategic truth- telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 METHODOLOGY � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 BACKGROUND �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 19 I. RESTRICTIONS ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 25 II� IMPACTS OF AID RESTRICTIONS ON DISPLACED POPULATIONS IN KACHIN STATE� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma. and the Shan States. in Five Volumes. Compiled from Official Papers by J. George Scott, Barrister-At-L

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA. AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT, BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E,M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. I. RANGOON: PRINTRD BY THE SUPERINTENDENT GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME I Page. Page. Page. A-eng 1 A-lôn-gyi 8 Auk-kyin 29 Ah Hmun 2 A-Ma ib ib. A-hlè-ywa ib. Amarapura ib. Auk-myin ib. Ai-bur ib. 23 Auk-o-a-nauk 30 Ai-fang ib. Amarapura Myoma 24 Auk-o-a-she ib. Ai-ka ib. A-meik ib. Auk-sa-tha ib. Aik-gyi ib. A-mi-hkaw ib. Auk-seik ib. Ai-la ib. A-myauk-bôn-o ib. Auk-taung ib. Aing-daing ib. A-myin ib. Auk-ye-dwin ib. Aing-daung ib. Anauk-dônma 25 Auk-yo ib. Aing-gaing 3 A-nauk-gôn ib. Aung ib. Aing-gyi ib. A-nsuk-ka-byu ib. Aung-ban-chaung ib. -- ib. A-nauk-kaing ib. Aung-bin-le ib. Aing-ma ib. A-nauk-kyat-o ib. Aung-bôn ib. -- ib. A-nauk-let-tha-ma ib. Aung-ga-lein-kan ib. -- ib. A-nauk-pet ib. Aung-kè-zin ib. -- ib. A-nauk-su ib. Aung-tha 31 -- ib ib ib. Aing-she ib. A-nauk-taw ib ib. Aing-tha ib ib ib. Aing-ya ib. A-nauk-yat ib. -

Seeking Accountability for Ending Impunity in Burma Analysis of War Crimes

Seeking Accountability for Ending Impunity in Burma Analysis of War Crimes Taking Place in Ethnic States Northern Shan State Karenni State Kachin State Contents Acknowledgement 1 Executive Summary 2 Introduction Part I A Brief Background of War Crimes 4 Part II Geopolitical Importance of the Mong Ko Territory 10 Part III Types of War Crimes 14 Part IV Excessive Use of Military Might, Resulted in Commission of Heinous War Crimes (Using the Detained Villagers as Human Shield) 15 Part V Independent Status of the Karenni State, Natural Resources Exploitation and War Crime 22 Part VI The Economic Relevance of the Tanai Territory, The Self-determination and War Crimes 28 Part VII Superior/Command Responsibility & Chain of Command (Mong Ko War Crimes) 39 Part VIII Concluding Analysis and Recommendations 43 Legal Aid Network is committed to facilitate efforts of grassroots people and activists, civil society organizations, lawyers and legal teams which aim to achieve human rights by establishing a peaceful, free, just and developed society with the underpinnings of genuine principles of the Rule of Law, mainly from legal aspect. Legal Aid Network is an independent organization. It is neither aligned nor is it under the authority of any political organization. [email protected] www.legalaidnetwork.org S E E K I N G ACCOUN TABILITY Acknowledgement We wish to thank the Burma Relief Center (BRC), which has assisted LAN in various ways to produce this report, and Civil Rights Defenders (CRD), which has funded us so that LAN‘s War Crimes Evidence Collection Group (WCECG) and relevant legal staff can operate effectively on the ground in ethnic states in Burma/Myanmar. -

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER July 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

The Kokang Casino Dream

ISSUES SIGN UP NOW Laukkai is already home to around 30 casinos and 50 hotels, none of which are licensed by Nay Pyi Taw. (Photo | Fully Light Golden Triangle Media) The Kokang casino dream JULY 23, 2020 Local politicians in a border region known for its frequent outbreaks of violence hope to transform it into the “next Macau”, but will have to overcome instability, politics and corruption to achieve their vision. By NANDA | FRONTIER A group of heavily armed gunmen sneak into town and storm three casinos. A pitched battle ensues; one person is killed and almost 300 staff are taken hostage. When the shooting ends, about 20 burned-out cars lie on the road in front of the hotels. The gunmen make off with a huge sum – said to be many tens of millions of dollars. It might sound like a scene from a Hollywood movie, but it’s not: the robbery took place just three years ago in Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in eastern Shan State. On March 6, 2017, members of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, a rebel armed group, raided the Fully Light, Kyinfu and Kyin Kyan hotel casinos, all of which are linked to a rival armed group, the Kokang Border Guard Force, which is part of the Tatmadaw. In a country where most people have little direct experience of armed conict, the attack further cemented Laukkai’s reputation as a violent and crime-ridden frontier town. But Laukkai’s leaders are determined to conne violent rebellion to history. -

Why Burma's Peace Efforts Have Failed to End Its Internal Wars

PEACEWORKS Why Burma’s Peace Efforts Have Failed to End Its Internal Wars By Bertil Lintner NO. 169 | OCTOBER 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 169 | OCTOBER 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT Supported by the Asia Center’s Burma program at the United States Institute of Peace to provide policymakers and the general public with a better understanding of Burma’s eth- PEACE PROCESSES nic conflicts, this report examines the country’s experiences of peace efforts and why they have failed to end its wars, and suggests ways forward to break the present stalemate. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Bertil Lintner has covered Burma’s civil wars and related issues, such as Burmese pol- itics and the Golden Triangle drug trade, for nearly forty years. Burma correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review from 1982 to 2004, he now writes for Asia Times and is the author of several books about Burma’s civil war and ethnic strife. Cover photo: A soldier from the Myanmar army provides security as ethnic Karens attend a ceremony to mark Karen State Day in Hpa-an, Karen State, on November 7, 2014. (Photo by Khin Maung Win/AP) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Update by the Shan Human Rights Foundation December 28, 2016

Update by the Shan Human Rights Foundation December 28, 2016 Looting, arbitrary arrest, torture, forced labour by Burma Army in Muse, northern Shan State 1. Looting, damage of villagers’ houses by Burma Army ID 33 troops in Pang Hsai, northern Shan State On 30 November 2016, Burma Army troops under Infantry Division 33 looted and damaged fourteen houses at Wan Khong Long village, Pang Hsai, Muse township, northern Shan State. There are 60 households in Wan Khong Long, with a population of 310 people. Almost all the inhabitants had fled their homes due to the heavy fighting about one mile north, at Wan Gawng Zong and Wan Nam Dao, between the Burma Army and the Northern Alliance (comprising the Kachin Independence Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and Arakan Army). A monk who had remained in Wan Khong Long village saw Burma Army troops breaking down doors, entering houses and looting villagers’ property. On the same day, a villager called Sai Tun Aung, who was driving his motorcycle from Wan Gawng Zong, arrived at Wan Khong Long and was shot at by the Burma Army ID 33 troops in the village. Luckily, he was not hit. The list of property looted and damaged by the Burma Army in Wan Khong Long is as follows: No. Villager’s names Property looted, damaged 1. Lung Ye Mai, Ba Kham Leng One camera, costing 410,000 kyat (300 USD) Two pairs of ear-rings (costing 226,000 kyat (170 USD) Goods for sale in their shop, costing 478,500 (360 USD) 40,000 Kyat (30 USD) and 600yuan(85 USD) in cash 2. -

Myanmar, the People’S Republic of China (Specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors (the Assessment) to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. The Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the 22nd GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program (GMS) The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty. Established in 1966, it is owned by 67 members— 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance.