Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Wohlstetter's Legacy: the Neo-Cons, Not Carter, Killed

SPECIAL REPORT: NUCLEAR SABOTAGE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER’S LEGACY Wohlstetter was even stranger than the “Dr. Strangelove” depicted in the 1964 movie of that name. An early draft of the film was titled “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” the same title as Wohlstetter’s best-known unclassified work. Here, a still from the film. tives—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Zalmay Khalilzad, to name a few. In Wohlstetter’s circle of influence were also Ahmed Chalabi (whom Wohlstetter championed), Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.), Sen. Robert Dole (R- Kan.), and Margaret Thatcher. Wohlstetter himself was a follower of Bertrand Russell, not only in mathematics, but in world outlook. The pseudo-peacenik Russell had called for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, after World War II and before the Soviets developed the bomb, as a prelude to his plan for bully- ing nations into a one-world government. Russell, a raving Malthusian, opposed economic development, especially in the Third World. Admirer Jude Wanniski wrote of Wohlstetter in an obituary, “[I]t is no exaggeration, I think, to say that Wohlstetter was the most influential unknown man in the world for the past half century, and easily in the top ten in importance of all men.” “Albert’s decisions were not automat- ically made official policy at the White House,” Wanniski wrote, “but Albert’s The Neo-Cons, Not Carter, genius and his following were such in the places where it counted in the Establishment that if his views were Killed Nuclear Energy resisted for more than a few months, it -

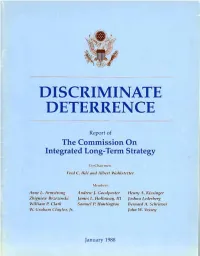

Discriminate Deterrence

DISCRIMINATE DETERRENCE Report of The Commission On Integrated Long-Term Strategy Co -C. I lairmea: Fred C. lkle and Albert Wohlstetter Moither, Anne L. Annsinmg Andrew l. Goodraster flenry /1 Kissinger Zbign ei Brzezinski fames L. Holloway, Ur Joshua Lederberg William P. Clark Samuel P. Huntington Bernard A. Schriever tV. Graham Ciaytor, John W. Vessey January 1988 COMMISSION ON INTEGRATED LONG-TERM STRATEGY January 11. 1988 MEMORANDUM FOR: THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE THE ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS We are pleased to present this final report of Our Commission. Pursuant to your initial mandate, the report proposes adjustments to US. military strategy in view of a changing security environment in the decades ahead. Over the last fifteen months the Commission has received valuable counsel from members of Congress, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Service Chiefs. and the Presdent's Science Advisor, Members of the National Security Council Staff, numerous professionals in the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and a broad range of specialists outside the government provided unstinting support. We are also indebted to the Commission's hardworking staff. The Commission was supported generously by several specialized study groups that closely analyzed a number of issues, among them: the security environment for the next twenty years, the role of advanced technology in military systems, interactions between offensive and defensive systems on the periphery of the Soviet Union, and the U.S, posture in regional conflicts around the world. Within the next few months, these study groups will publish detailed findings of their own. -

Charlie Sykes

CHARLIE SYKES EDITOR-AT-LARGE, THE BULWARK Quick Summary Life in Brief Former conservative radio host and Wisconsin Hometown: Seattle, WA Republican kingmaker who gained national prominence as a leading voice in the Never Trump Current Residence: Mequon, WI movement and created the Bulwark website as a messaging arm for like-minded conservatives Education: • BA, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, • Love for journalism and politics heavily influenced 1975 by his father • Self-described “recovering liberal” who criticizes Family: both political parties for inflexibility and for • Married to Janet Riordan alienating those who reject status quo • Three children, two grandchildren • As conservative radio host, cultivated significant influence in Wisconsin GOP politics – quickly Work History: becoming a go-to stop for Republican candidates; • Editor-at-Large, The Bulwark, 2019- drew significant attention to issues like school Present choice • Host, The Daily Standard, 2018 • Became national figure after refusing to support • Contributing editor, The Weekly Donald Trump Standard • Co-founded the Bulwark with Bill Kristol, which • Contributor, NBC/MSNBC, 2016-present has become a leading mouthpiece of the Never • Host, Indivisible WNYC, 2017 Trump conservative movement • Editor-in-Chief, Right Wisconsin • Considers himself a “political orphan” in the era of • Radio show host, WTMJ, 1999-2016 Trump after exile from conservative movement • Radio host, WISN, 1989-93 whose political identity has changed many times • PR for Dave Schulz, Milwaukee -

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Charles Murray, Scholar, American Enterprise Institute

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Charles Murray, scholar, American Enterprise Institute Table of Contents I: 0:00 – 5:55 II: I: (0:15 –) KRISTOL: Hi, I’m Bill Kristol. Welcome back to CONVERSATIONS. I’m very pleased to be joined today again by Charles Murray, scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, author of many important books: Losing Ground – when was that? 1984? – The Bell Curve in the mid-90s, and Coming Apart, about four years ago. I would say, I’m not sure there’s a social commentator who’s written as many important books over the last few decades as Charles so it is a great pleasure and honor to have you here. And you’re going to explain the current moment, right? MURRAY: With that kind of introduction I suppose I’m obligated to. KRISTOL: Exactly right. So what – this is the very beginning of August of 2016. People are – someone wrote something in the New York Times yesterday giving you credit for presciently seeing that Trump or Trumpism, I guess, was going to happen. Did you see it, and what do you make of it? MURRAY: I knew that we were going to have a problem with the white working class, and actually, I guess I’ll blow my own horn and say in 1993 for The Wall Street Journal, I had a long article called “The Coming White Underclass.” If you go back and read that – but this is not rocket science, it simply was the trend lines for out-of-wedlock births among working-class whites at that point had been spiking upward. -

The Lost Generation in American Foreign Policy How American Influence Has Declined, and What Can Be Done About It

September 2020 Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE JAMES DOBBINS, GABRIELLE TARINI, ALI WYNE The Lost Generation in American Foreign Policy How American Influence Has Declined, and What Can Be Done About It n the aftermath of World War II, the United States accepted the mantle of global leadership and worked to build a new global order based on the principles of nonaggression and open, nondiscriminatory trade. An early pillar of this new Iorder was the Marshall Plan for European reconstruction, which British histo- rian Norman Davies has called “an act of the most enlightened self-interest in his- tory.”1 America’s leaders didn’t regard this as charity. They recognized that a more peaceful and more prosperous world would be in America’s self-interest. American willingness to shoulder the burdens of world leadership survived a costly stalemate in the Korean War and a still more costly defeat in Vietnam. It even survived the end of the Cold War, the original impetus for America’s global activ- ism. But as a new century progressed, this support weakened, America’s influence slowly diminished, and eventually even the desire to exert global leadership waned. Over the past two decades, the United States experienced a dramatic drop-off in international achievement. A generation of Americans have come of age in an era in which foreign policy setbacks have been more frequent than advances. C O R P O R A T I O N Awareness of America’s declining influence became immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic and by Obama commonplace among observers during the Barack Obama with Ebola, has also been widely noted. -

A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship

VOLUME XVI, NUMBER 2, SPRING 2016 A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship Bradley C.S. R. Shep Watson: Melnick: Russell Kirk Ending Extreme Michael Poverty Nelson: Political Sex Allen C. Scandals Guelzo: Did the Angelo M. Slaves Free Codevilla: emselves? John Quincy Adams Robert K. Faulkner: James V. Heroes, Schall, S.J.: Old & Modern New Catholic ought Anthony Esolen: James W. e Iliad Ceaser: Scruton vs. Mark the Left Helprin: Defense Is Missing in Action A Publication of the Claremont Institute PRICE: $6.95 IN CANADA: $8.95 mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm Book Review by Allen C. Guelzo Up from Slavery The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States, by Ira Berlin. Harvard University Press, 240 pages, $22.95 Eighty-Eight Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777–1865, by Patrick Rael. University of Georgia Press, 400 pages, $89.95 (cloth), $32.95 (paper) elf-help has a long tradition in free-market narcissists like Robert Ringer in t is odd, however, to see over the American life. In its earliest form, Pu- his bestseller Looking Out for Number One last 25 years the emergence of a similar Sritan self-help manuals offered guid- (1977): “Life is like a giant pinspotter in a go- Ibrand of self-help in the midst of the his- ance to the spiritual pilgrim in detecting the liath’s bowling alley. Over the long haul, most tory of slave emancipation. We may think we signs of grace and whether one was on the people end up exactly where they deserve to know the outlines of emancipation’s history, path to heaven. -

The Watergate Story (Washingtonpost.Com)

The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) Hello corderoric | Change Preferences | Sign Out TODAY'S NEWSPAPER Subscribe | PostPoints NEWS POLITICS OPINIONS BUSINESS LOCAL SPORTS ARTS & GOING OUT JOBS CARS REAL RENTALS CLASSIFIEDS LIVING GUIDE ESTATE SEARCH: washingtonpost.com Web | Search Archives washingtonpost.com > Politics> Special Reports 'Deep Throat' Mark Felt Dies at 95 The most famous anonymous source in American history died Dec. 18 at his home in Santa Rosa, Calif. "Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now before Congress and ultimately the American people." A curious crime, two young The courts, the Congress and President Nixon refuses to After 30 years, one of reporters, and a secret source a special prosecutor probe release the tapes and fires the Washington's best-kept known as "Deep Throat" ... the burglars' connections to special prosecutor. A secrets is exposed. —Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox after his Washington would be the White House and decisive Supreme Court firing, Oct. 20, 1973 changed forever. discover a secret taping ruling is a victory for system. investigators. • Q&A Transcript: John Dean's new book "Pure Goldwater" (May 6, 2008) • Obituary: Nixon Aide DeVan L. Shumway, 77 (April 26, 2008) Wg:1 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/index.html#chapters[6/14/2009 6:06:08 PM] The Watergate Story (washingtonpost.com) • Does the News Matter To Anyone Anymore? (Jan. 20, 2008) • Why I Believe Bush Must Go (Jan. 6, 2008) Key Players | Timeline | Herblock -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship

VOLUME XIX, NUMBER 2, SPRING 2019 A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship Michael Anton: William Voegeli: Christopher Caldwell: In Praise of Tucker Carlson Socialism for Dummies Hungary vs. Liberalism Larry P.Arnn: Joseph Epstein: Martha Bayles: Andrew Roberts’s Churchill The P.C. Menace Cold War Movies John Fonte: Mark Helprin: David Gelernter: Reihan Salam’s Melting Pot Memo from Harvard Admissions Up from Darwinism A Publication of the Claremont Institute PRICE: $6.95 IN CANADA: $8.95 mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm THE CRB INTERVIEW CRB editor Charles R. Kesler recently sat down with Norman Podhoretz at his home in New York. In a wide-ranging conversation, the longtime editor-in-chief of Commentary and one of the founders of neoconservatism, who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2004, revealed his thoughts on Donald Trump, Never Trumpers, Iraq, immigration, 2020 predictions, and more. CRB: Let’s start by talking about Donald real estate world is a world unto its own. The CRB: Some people say that Trump has a blue Trump and you. In the first sentence of the competition is very fierce, you’re dealing with collar sensibility. Do you see that? first chapter of your bookMaking It, recent- many, many clever people. I think it was Tom ly republished by the New York Review of Klingenstein who said he always thought NP: I do see it and even before Trump— Books Press, of all people— Trump was Jewish because he fit in so well long before Trump—actually going back to with the real-estatenicks in Manhattan, most when I was in the army in the 1950s, I got to NP: Hell froze over! of whom were, and are, Jewish. -

Mirrors of Modernization: the American Reflection in Turkey

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey Begum Adalet University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Adalet, Begum, "Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1186. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1186 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1186 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey Abstract This project documents otherwise neglected dimensions entailed in the assemblage and implementations of political theories, namely their fabrication through encounters with their material, local, and affective constituents. Rather than emanating from the West and migrating to their venues of application, social scientific theories are fashioned in particular sites where political relations can be staged and worked upon. Such was the case with modernization theory, which prevailed in official and academic circles in the United States during the early phases of the Cold War. The theory bore its imprint on a series of developmental and infrastructural projects in Turkey, the beneficiary of Marshall Plan funds and academic exchange programs and one of the theory's most important models. The manuscript scrutinizes the corresponding sites of elaboration for the key indices of modernization: the capacity for empathy, mobility, and hospitality. In the case of Turkey the sites included survey research, the implementation of a highway network, and the expansion of the tourism industry through landmarks such as the Istanbul Hilton Hotel. -

In the Decade Immediately Following the Second World War, Many Of

‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Julian Tzara Nemeth August 2007 2 This thesis titled ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought by JULIAN TZARA NEMETH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract NEMETH, JULIAN TZARA., M.A, August 2007, History ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought (108 pp.) Director of Thesis: Kevin Mattson In the early years of the Cold War, more than one hundred American academics lost their jobs because university administrators suspected them of Communist Party membership. How did intellectuals respond to this crisis? Referring to contemporary books, articles, organizational statements, and correspondence, I argue that disputes over academic freedom helped shatter a tenuous liberal consensus, unite conservatives, and challenge defenses of professorial liberty among academia’s largest professional organization, the American Association of University Professors. Specifically, I show how Sidney Hook and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s dispute over academic freedom was representative of larger quarrels among liberals over McCarthyism. Conversely, I demonstrate that conservatives such as William Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk overcame serious differences on academic freedom to present a united front against liberalism, in and outside of the academy. Finally, I show the difficulty an organization such as the AAUP encounters when defending professional values in a democratic society. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism.