Global Epidemiology of Sporotrichosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms That Underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces

Virulence ISSN: 2150-5594 (Print) 2150-5608 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/kvir20 Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier & Bruce S. Klein To cite this article: Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier & Bruce S. Klein (2018): Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces, Virulence, DOI: 10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group© Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier and Bruce S. Klein Accepted author version posted online: 13 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 15 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=kvir20 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Journal: Virulence DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces Joseph A. McBride, MDa,b,d, Gregory M. Gauthier, MDa,d, and Bruce S. Klein, MDa,b,c a Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 600 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792, USA; b Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1675 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792, USA; c Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1550 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA. -

Mycosphere Notes 225–274: Types and Other Specimens of Some Genera of Ascomycota

Mycosphere 9(4): 647–754 (2018) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/9/4/3 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Mycosphere Notes 225–274: types and other specimens of some genera of Ascomycota Doilom M1,2,3, Hyde KD2,3,6, Phookamsak R1,2,3, Dai DQ4,, Tang LZ4,14, Hongsanan S5, Chomnunti P6, Boonmee S6, Dayarathne MC6, Li WJ6, Thambugala KM6, Perera RH 6, Daranagama DA6,13, Norphanphoun C6, Konta S6, Dong W6,7, Ertz D8,9, Phillips AJL10, McKenzie EHC11, Vinit K6,7, Ariyawansa HA12, Jones EBG7, Mortimer PE2, Xu JC2,3, Promputtha I1 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 2 Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, China 3 World Agro Forestry Centre, East and Central Asia, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China 4 Center for Yunnan Plateau Biological Resources Protection and Utilization, College of Biological Resource and Food Engineering, Qujing Normal University, Qujing, Yunnan 655011, China 5 Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Microbial Genetic Engineering, College of Life Sciences and Oceanography, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China 6 Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 7 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 8 Department Research (BT), Botanic Garden Meise, Nieuwelaan 38, BE-1860 Meise, Belgium 9 Direction Générale de l'Enseignement non obligatoire et de la Recherche scientifique, Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Rue A. -

Fungal Infection in the Lung

CHAPTER Fungal Infection in the Lung 52 Udas Chandra Ghosh, Kaushik Hazra INTRODUCTION The following risk factors may predispose to develop Pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of death in fungal infections in the lungs 6 1, 2 developed countries . Though the fungal cause of 1. Acute leukemia or lymphoma during myeloablative pneumonia occupies a minor portion in the immune- chemotherapy competent patients, but it causes a major role in immune- deficient populations. 2. Bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation Fungi may colonize body sites without producing disease or they may be a true pathogen, generating a broad variety 3. Solid organ transplantation on immunosuppressive of clinical syndromes. treatment Fungal infections of the lung are less common than 4. Prolonged corticosteroid therapy bacterial and viral infections and very difficult for 5. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome diagnosis and treatment purposes. Their virulence varies from causing no symptoms to death. Out of more than 1 6. Prolonged neutropenia from various causes lakh species only few fungi cause human infection and 7. Congenital immune deficiency syndromes the most vulnerable organs are skin and lungs3, 4. 8. Postsplenectomy state RISK FACTORS 9. Genetic predisposition Workers or farmers with heavy exposure to bird, bat, or rodent droppings or other animal excreta in endemic EPIDEMIOLOGY OF FUNGAL PNEUMONIA areas are predisposed to any of the endemic fungal The incidences of invasive fungal infections have pneumonias, such as histoplasmosis, in which the increased during recent decades, largely because of the environmental exposure to avian or bat feces encourages increasing size of the population at risk. This population the growth of the organism. -

Monoclonal Antibodies As Tools to Combat Fungal Infections

Journal of Fungi Review Monoclonal Antibodies as Tools to Combat Fungal Infections Sebastian Ulrich and Frank Ebel * Institute for Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, D-80539 Munich, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 November 2019; Accepted: 31 January 2020; Published: 4 February 2020 Abstract: Antibodies represent an important element in the adaptive immune response and a major tool to eliminate microbial pathogens. For many bacterial and viral infections, efficient vaccines exist, but not for fungal pathogens. For a long time, antibodies have been assumed to be of minor importance for a successful clearance of fungal infections; however this perception has been challenged by a large number of studies over the last three decades. In this review, we focus on the potential therapeutic and prophylactic use of monoclonal antibodies. Since systemic mycoses normally occur in severely immunocompromised patients, a passive immunization using monoclonal antibodies is a promising approach to directly attack the fungal pathogen and/or to activate and strengthen the residual antifungal immune response in these patients. Keywords: monoclonal antibodies; invasive fungal infections; therapy; prophylaxis; opsonization 1. Introduction Fungal pathogens represent a major threat for immunocompromised individuals [1]. Mortality rates associated with deep mycoses are generally high, reflecting shortcomings in diagnostics as well as limited and often insufficient treatment options. Apart from the development of novel antifungal agents, it is a promising approach to activate antimicrobial mechanisms employed by the immune system to eliminate microbial intruders. Antibodies represent a major tool to mark and combat microbes. Moreover, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are highly specific reagents that opened new avenues for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. -

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program Test Event Critique January 2014 Table of Contents Mycology Laboratory 2 Mycology Proficiency Testing Program 3 Test Specimens & Grading Policy 5 Test Analyte Master Lists 7 Performance Summary 11 Commercial Device Usage Statistics 13 Mold Descriptions 14 M-1 Stachybotrys chartarum 14 M-2 Aspergillus clavatus 18 M-3 Microsporum gypseum 22 M-4 Scopulariopsis species 26 M-5 Sporothrix schenckii species complex 30 Yeast Descriptions 34 Y-1 Cryptococcus uniguttulatus 34 Y-2 Saccharomyces cerevisiae 37 Y-3 Candida dubliniensis 40 Y-4 Candida lipolytica 43 Y-5 Cryptococcus laurentii 46 Direct Detection - Cryptococcal Antigen 49 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Yeast 52 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Mold (Educational) 54 1 Mycology Laboratory Mycology Laboratory at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) is a reference diagnostic laboratory for the fungal diseases. The laboratory services include testing for the dimorphic pathogenic fungi, unusual molds and yeasts pathogens, antifungal susceptibility testing including tests with research protocols, molecular tests including rapid identification and strain typing, outbreak and pseudo-outbreak investigations, laboratory contamination and accident investigations and related environmental surveys. The Fungal Culture Collection of the Mycology Laboratory is an important resource for high quality cultures used in the proficiency-testing program and for the in-house development and standardization of new diagnostic tests. Mycology Proficiency Testing Program provides technical expertise to NYSDOH Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP). The program is responsible for conducting the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-compliant Proficiency Testing (Mycology) for clinical laboratories in New York State. All analytes for these test events are prepared and standardized internally. -

Sporothrix Schenckii and Sporotrichosis

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2006) 78(2): 293-308 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) ISSN 0001-3765 www.scielo.br/aabc Sporothrix schenckii and Sporotrichosis LEILA M. LOPES-BEZERRA1, ARMANDO SCHUBACH2 and ROSANE O. COSTA3 1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro/UERJ Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcantara Gomes, Departamento de Biologia Celular e Genética Rua São Francisco Xavier, 524 PHLC, sl. 205, Maracanã 20550-013 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil 2Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto de Pesquisa Clínica Evandro Chagas Departamento de Doenças Infecciosas, Av. Brasil 4365, Manguinhos 21040-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil 3Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro/UERJ, Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto Av. 28 de Setembro 77, Vila Isabel, 20551-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil Manuscript received on September 26, 2005; accepted for publication on October 10, 2006 presented by LUIZ R. TRAVASSOS ABSTRACT For a long time sporotrichosis has been regarded to have a low incidence in Brazil; however, recent studies demonstrate that not only the number of reported cases but also the incidence of more severe or atypical clinical forms of the disease are increasing. Recent data indicate that these more severe forms occur in about 10% of patients with confirmed diagnosis. The less frequent forms, mainly osteoarticular sporotrichosis, might be associated both with patient immunodepression and zoonotic transmission of the disease. The extracutaneous form and the atypical forms are a challenge to a newly developed serological test, introduced as an auxiliary tool for the diagnosis of unusual clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Key words: sporotrichosis, diagnosis, epidemiology, drugs, cell wall, antigens. -

New Xerophilic Species of Penicillium from Soil

Journal of Fungi Article New Xerophilic Species of Penicillium from Soil Ernesto Rodríguez-Andrade, Alberto M. Stchigel * and José F. Cano-Lira Mycology Unit, Medical School and IISPV, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV), Sant Llorenç 21, Reus, 43201 Tarragona, Spain; [email protected] (E.R.-A.); [email protected] (J.F.C.-L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-977-75-9341 Abstract: Soil is one of the main reservoirs of fungi. The aim of this study was to study the richness of ascomycetes in a set of soil samples from Mexico and Spain. Fungi were isolated after 2% w/v phenol treatment of samples. In that way, several strains of the genus Penicillium were recovered. A phylogenetic analysis based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS), beta-tubulin (BenA), calmodulin (CaM), and RNA polymerase II subunit 2 gene (rpb2) sequences showed that four of these strains had not been described before. Penicillium melanosporum produces monoverticillate conidiophores and brownish conidia covered by an ornate brown sheath. Penicillium michoacanense and Penicillium siccitolerans produce sclerotia, and their asexual morph is similar to species in the section Aspergilloides (despite all of them pertaining to section Lanata-Divaricata). P. michoacanense differs from P. siccitol- erans in having thick-walled peridial cells (thin-walled in P. siccitolerans). Penicillium sexuale differs from Penicillium cryptum in the section Crypta because it does not produce an asexual morph. Its ascostromata have a peridium composed of thick-walled polygonal cells, and its ascospores are broadly lenticular with two equatorial ridges widely separated by a furrow. All four new species are xerophilic. -

Sporotrichosis

8/6/2011 Sporotrichosis • Alternative name –Rose Handler’s Disease Named due to fungal infection resulting from thorn pricks or barbs, Sporotrichosis handling of sphagnum moss or by slivers from Pam Galioto, Megan Lileas, Tom wood or lumber Mariani, and Katie Olenick – Kingdom: Fungi • Only one active species – Phylum: Ascomycota –Sporothrix schenckii • Thermally dimorphic – Class: Euascomycetes fungus which is distributed worldwide – Order: Ophiostomatales • Isolated from soil, living and decomposing plants, woods, and peat moss – Family: Ophiostomataceae – Genus: Sporothrix Geographical Distribution Life Cycle Phase 1 – Hyphal Phase • Exists worldwide, but uncommon in •25°C, grows slowly United States •Conidospores • Peru has hyperendemicity for infection •Pigmented white, cream, or black • More common in temperate or tropical •Flower formation zones Phase 2 – Yeast Phase •37°C •Pigmented white or greyish-yellow •Spherical/budding yeast colonies 1 8/6/2011 Epidemiology Pathogenesis At risk - Prevention – •Generally enters body through skin •Handling thorny plants, baled •Wear gloves when handling prick, cuts, or small punctures hay, moss wires, bushes, etc. •Can be inhaled •Nursery workers •Avoid contact with •Cutaneous, pulmonary, or •Children playing on baled hay sphagnum moss disseminated infection •Rose gardeners •Proper handling of •Joints, lungs, and central nervous •Greenhouse workers laboratory equipment system have occurred •First nodule in 1 to 12 weeks •Can infect animals •Can cause arthritis, meningitis, pneumonitis, or -

Davis Overview of Fungi and Diseases 2014

JHH ID Tutorials Dr Josh Davis December 2014 MYCOLOGY OVERVIEW 1. OVERVIEW. It is estimated that there are 1.5 million extant species of fungi on Earth, of which 60,000 have been described/named; of these only approximately 400 species have ever been described to cause disease in humans and only approximately 20 do so with any frequency. Many others are plant pathogens or symbionts. At least 13,500 fungal species form lichens, symbiotic partnerships between fungi (usually ascomycota) and photosynthetic microbes (eg. algae, cyanobacteria). 2. CLASSIFICATION. There are several confusing/overlapping classifications systems for fungi. 2.1 Biological Kingdom FUNGI; Phyla: 2.1.1 Phylum Zygomycota – Agents of zygomycosis, “mucormycosis”. Most primitive fungi. Broad, ribbon-like hyphae, no septae. Generally grow fast on agar (“lid-lifters”). 2.1.1.1 Order Mucorales – eg. Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Saskanaea, Cuninghamella 2.1.1.2 Order Entomophthorales – Basidiobolus, Canidiobolus 2.1.2 Phylum Basidiomycota – Mushrooms, jelly fungi, smuts, rusts, stinkhorns . and the teleomorph of cryptococcus! 2.1.3 Phylum Ascomycota – e.g. Pseudoallescheria, Curvularia, Saccharomyces. 2.1.4 Phylum Deuteromycota, or Fungi Imperfecti. Not a true phylum. Contains asexual (“imperfect”) forms of fungi (anamorphs), most of which have not had a sexual form described. Most human pathogens are in this group – eg: Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus, Scedosporium, Alternaria, Trichophyton, Cladosporium etc. etc. 1. Sporotrix at 37 and 25 degrees; 2. Aspergillus fumigatus, niger, terreus, flavus (L to R); 3. Candida albicans 2.2 Morphological 2.2.1 Broad classification - Yeasts, Moulds and Dimorphic Fungi 2.2.1.1 Yeasts are single-celled organisms which reproduce by budding and grow as smooth colonies on agar. -

Polyketides, Toxins and Pigments in Penicillium Marneffei

Toxins 2015, 7, 4421-4436; doi:10.3390/toxins7114421 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Review Polyketides, Toxins and Pigments in Penicillium marneffei Emily W. T. Tam 1, Chi-Ching Tsang 1, Susanna K. P. Lau 1,2,3,4,* and Patrick C. Y. Woo 1,2,3,4,* 1 Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.W.T.T.); [email protected] (C.-C.T.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Emerging Infectious Diseases, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong 3 Research Centre of Infection and Immunology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong 4 Carol Yu Centre for Infection, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong * Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.K.P.L.); [email protected] (P.C.Y.W.); Tel.: +852-2255-4892 (S.K.P.L. & P.C.Y.W.); Fax: +852-2855-1241 (S.K.P.L. & P.C.Y.W.). Academic Editor: Jiujiang Yu Received: 18 September 2015 / Accepted: 22 October 2015 / Published: 30 October 2015 Abstract: Penicillium marneffei (synonym: Talaromyces marneffei) is the most important pathogenic thermally dimorphic fungus in China and Southeastern Asia. The HIV/AIDS pandemic, particularly in China and other Southeast Asian countries, has led to the emergence of P. marneffei infection as an important AIDS-defining condition. Recently, we published the genome sequence of P. marneffei. In the P. marneffei genome, 23 polyketide synthase genes and two polyketide synthase-non-ribosomal peptide synthase hybrid genes were identified. -

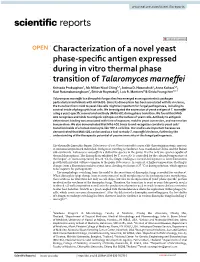

Characterization of a Novel Yeast Phase-Specific Antigen Expressed

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Characterization of a novel yeast phase‑specifc antigen expressed during in vitro thermal phase transition of Talaromyces marnefei Kritsada Pruksaphon1, Mc Millan Nicol Ching2,3, Joshua D. Nosanchuk4, Anna Kaltsas5,6, Kavi Ratanabanangkoon7, Sittiruk Roytrakul8, Luis R. Martinez9 & Sirida Youngchim10* Talaromyces marnefei is a dimorphic fungus that has emerged as an opportunistic pathogen particularly in individuals with HIV/AIDS. Since its dimorphism has been associated with its virulence, the transition from mold to yeast‑like cells might be important for fungal pathogenesis, including its survival inside of phagocytic host cells. We investigated the expression of yeast antigen of T. marnefei using a yeast‑specifc monoclonal antibody (MAb) 4D1 during phase transition. We found that MAb 4D1 recognizes and binds to antigenic epitopes on the surface of yeast cells. Antibody to antigenic determinant binding was associated with time of exposure, mold to yeast conversion, and mammalian temperature. We also demonstrated that MAb 4D1 binds to and recognizes conidia to yeast cells’ transition inside of a human monocyte‑like THP‑1 cells line. Our studies are important because we demonstrated that MAb 4D1 can be used as a tool to study T. marnefei virulence, furthering the understanding of the therapeutic potential of passive immunity in this fungal pathogenesis. Te thermally dimorphic fungus Talaromyces (Penicillium) marnefei causes a life-threatening systemic mycosis in immunocompromised individuals living in or traveling to Southeast Asia, mainland of China, and the Indian sub-continents. Talaromyces marnefei is a distinctive species in the genus. It is the only one species capable of thermal dimorphism. -

Neglected Fungal Zoonoses: Hidden Threats to Man and Animals

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector REVIEW Neglected fungal zoonoses: hidden threats to man and animals S. Seyedmousavi1,2,3, J. Guillot4, A. Tolooe5, P. E. Verweij2 and G. S. de Hoog6,7,8,9,10 1) Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, 2) Department of Medical Microbiology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 3) Invasive Fungi Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran, 4) Department of Parasitology- Mycology, Dynamyic Research Group, EnvA, UPEC, UPE, École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort, Maisons-Alfort, France, 5) Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, 6) CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, 7) Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8) Peking University Health Science Center, Research Center for Medical Mycology, Beijing, 9) Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China and 10) King Abdullaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Abstract Zoonotic fungi can be naturally transmitted between animals and humans, and in some cases cause significant public health problems. A number of mycoses associated with zoonotic transmission are among the group of the most common fungal diseases, worldwide. It is, however, notable that some fungal diseases with zoonotic potential have lacked adequate attention in international public health efforts, leading to insufficient attention on their preventive strategies. This review aims to highlight some mycoses whose zoonotic potential received less attention, including infections caused by Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei, Lacazia loboi, Emmonsia spp., Basidiobolus ranarum, Conidiobolus spp.