Sporothrix Schenckii and Sporotrichosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungal Infections from Human and Animal Contact

Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 4-25-2017 Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner Follow this and additional works at: https://aurora.org/jpcrr Part of the Bacterial Infections and Mycoses Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, and the Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Baumgardner DJ. Fungal infections from human and animal contact. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2017;4:78-89. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1418 Published quarterly by Midwest-based health system Advocate Aurora Health and indexed in PubMed Central, the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews (JPCRR) is an open access, peer-reviewed medical journal focused on disseminating scholarly works devoted to improving patient-centered care practices, health outcomes, and the patient experience. REVIEW Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner, MD Aurora University of Wisconsin Medical Group, Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, WI; Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI; Center for Urban Population Health, Milwaukee, WI Abstract Fungal infections in humans resulting from human or animal contact are relatively uncommon, but they include a significant proportion of dermatophyte infections. Some of the most commonly encountered diseases of the integument are dermatomycoses. Human or animal contact may be the source of all types of tinea infections, occasional candidal infections, and some other types of superficial or deep fungal infections. This narrative review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of anthropophilic dermatophyte infections primarily found in North America. -

Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms That Underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces

Virulence ISSN: 2150-5594 (Print) 2150-5608 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/kvir20 Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier & Bruce S. Klein To cite this article: Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier & Bruce S. Klein (2018): Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces, Virulence, DOI: 10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group© Joseph A. McBride, Gregory M. Gauthier and Bruce S. Klein Accepted author version posted online: 13 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 15 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=kvir20 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Journal: Virulence DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2018.1449506 Turning on Virulence: Mechanisms that underpin the Morphologic Transition and Pathogenicity of Blastomyces Joseph A. McBride, MDa,b,d, Gregory M. Gauthier, MDa,d, and Bruce S. Klein, MDa,b,c a Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 600 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792, USA; b Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Pediatrics, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1675 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792, USA; c Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1550 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA. -

Review Article Sporotrichosis: an Overview and Therapeutic Options

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Dermatology Research and Practice Volume 2014, Article ID 272376, 13 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/272376 Review Article Sporotrichosis: An Overview and Therapeutic Options Vikram K. Mahajan Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Dr. R. P. Govt. Medical College, Kangra, Tanda, Himachal Pradesh 176001, India Correspondence should be addressed to Vikram K. Mahajan; [email protected] Received 30 July 2014; Accepted 12 December 2014; Published 29 December 2014 Academic Editor: Craig G. Burkhart Copyright © 2014 Vikram K. Mahajan. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Sporotrichosis is a chronic granulomatous mycotic infection caused by Sporothrix schenckii, a common saprophyte of soil, decaying wood, hay, and sphagnum moss, that is endemic in tropical/subtropical areas. The recent phylogenetic studies have delineated the geographic distribution of multiple distinct Sporothrix species causing sporotrichosis. It characteristically involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue following traumatic inoculation of the pathogen. After a variable incubation period, progressively enlarging papulo-nodule at the inoculation site develops that may ulcerate (fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis) or multiple nodules appear proximally along lymphatics (lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis). Osteoarticular sporotrichosis or primary pulmonary sporotrichosis are rare and occur from direct inoculation or inhalation of conidia, respectively. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis or involvement of multiple visceral organs, particularly the central nervous system, occurs most commonly in persons with immunosuppression. Saturated solution of potassium iodide remains a first line treatment choice for uncomplicated cutaneous sporotrichosis in resource poor countries but itraconazole is currently used/recommended for the treatment of all forms of sporotrichosis. -

Fungal Infection in the Lung

CHAPTER Fungal Infection in the Lung 52 Udas Chandra Ghosh, Kaushik Hazra INTRODUCTION The following risk factors may predispose to develop Pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of death in fungal infections in the lungs 6 1, 2 developed countries . Though the fungal cause of 1. Acute leukemia or lymphoma during myeloablative pneumonia occupies a minor portion in the immune- chemotherapy competent patients, but it causes a major role in immune- deficient populations. 2. Bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation Fungi may colonize body sites without producing disease or they may be a true pathogen, generating a broad variety 3. Solid organ transplantation on immunosuppressive of clinical syndromes. treatment Fungal infections of the lung are less common than 4. Prolonged corticosteroid therapy bacterial and viral infections and very difficult for 5. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome diagnosis and treatment purposes. Their virulence varies from causing no symptoms to death. Out of more than 1 6. Prolonged neutropenia from various causes lakh species only few fungi cause human infection and 7. Congenital immune deficiency syndromes the most vulnerable organs are skin and lungs3, 4. 8. Postsplenectomy state RISK FACTORS 9. Genetic predisposition Workers or farmers with heavy exposure to bird, bat, or rodent droppings or other animal excreta in endemic EPIDEMIOLOGY OF FUNGAL PNEUMONIA areas are predisposed to any of the endemic fungal The incidences of invasive fungal infections have pneumonias, such as histoplasmosis, in which the increased during recent decades, largely because of the environmental exposure to avian or bat feces encourages increasing size of the population at risk. This population the growth of the organism. -

Monoclonal Antibodies As Tools to Combat Fungal Infections

Journal of Fungi Review Monoclonal Antibodies as Tools to Combat Fungal Infections Sebastian Ulrich and Frank Ebel * Institute for Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, D-80539 Munich, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 November 2019; Accepted: 31 January 2020; Published: 4 February 2020 Abstract: Antibodies represent an important element in the adaptive immune response and a major tool to eliminate microbial pathogens. For many bacterial and viral infections, efficient vaccines exist, but not for fungal pathogens. For a long time, antibodies have been assumed to be of minor importance for a successful clearance of fungal infections; however this perception has been challenged by a large number of studies over the last three decades. In this review, we focus on the potential therapeutic and prophylactic use of monoclonal antibodies. Since systemic mycoses normally occur in severely immunocompromised patients, a passive immunization using monoclonal antibodies is a promising approach to directly attack the fungal pathogen and/or to activate and strengthen the residual antifungal immune response in these patients. Keywords: monoclonal antibodies; invasive fungal infections; therapy; prophylaxis; opsonization 1. Introduction Fungal pathogens represent a major threat for immunocompromised individuals [1]. Mortality rates associated with deep mycoses are generally high, reflecting shortcomings in diagnostics as well as limited and often insufficient treatment options. Apart from the development of novel antifungal agents, it is a promising approach to activate antimicrobial mechanisms employed by the immune system to eliminate microbial intruders. Antibodies represent a major tool to mark and combat microbes. Moreover, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are highly specific reagents that opened new avenues for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. -

Application to Add Itraconazole and Voriconazole to the Essential List of Medicines for Treatment of Fungal Diseases – Support Document

Application to add itraconazole and voriconazole to the essential list of medicines for treatment of fungal diseases – Support document 1 | Page Contents Page number Summary 3 Centre details supporting the application 3 Information supporting the public health relevance and review of 4 benefits References 7 2 | Page 1. Summary statement of the proposal for inclusion, change or deletion As a growing trend of invasive fungal infections has been noticed worldwide, available few antifungal drugs requires to be used optimally. Invasive aspergillosis, systemic candidiasis, chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, fungal rhinosinusitis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, phaeohyphomycosis, histoplasmosis, sporotrichosis, chromoblastomycosis, and relapsed cases of dermatophytosis are few important concern of southeast Asian regional area. Considering the high burden of fungal diseases in Asian countries and its associated high morbidity and mortality (often exceeding 50%), we support the application of including major antifungal drugs against filamentous fungi, itraconazole and voriconazole in the list of WHO Essential Medicines (both available in oral formulation). The inclusion of these oral effective antifungal drugs in the essential list of medicines (EML) would help in increased availability of these agents in this part of the world and better prompt management of patients thereby reducing mortality. The widespread availability of these drugs would also stimulate more research to facilitate the development of better combination therapies. -

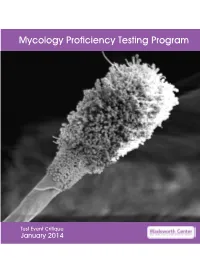

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program Test Event Critique January 2014 Table of Contents Mycology Laboratory 2 Mycology Proficiency Testing Program 3 Test Specimens & Grading Policy 5 Test Analyte Master Lists 7 Performance Summary 11 Commercial Device Usage Statistics 13 Mold Descriptions 14 M-1 Stachybotrys chartarum 14 M-2 Aspergillus clavatus 18 M-3 Microsporum gypseum 22 M-4 Scopulariopsis species 26 M-5 Sporothrix schenckii species complex 30 Yeast Descriptions 34 Y-1 Cryptococcus uniguttulatus 34 Y-2 Saccharomyces cerevisiae 37 Y-3 Candida dubliniensis 40 Y-4 Candida lipolytica 43 Y-5 Cryptococcus laurentii 46 Direct Detection - Cryptococcal Antigen 49 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Yeast 52 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Mold (Educational) 54 1 Mycology Laboratory Mycology Laboratory at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) is a reference diagnostic laboratory for the fungal diseases. The laboratory services include testing for the dimorphic pathogenic fungi, unusual molds and yeasts pathogens, antifungal susceptibility testing including tests with research protocols, molecular tests including rapid identification and strain typing, outbreak and pseudo-outbreak investigations, laboratory contamination and accident investigations and related environmental surveys. The Fungal Culture Collection of the Mycology Laboratory is an important resource for high quality cultures used in the proficiency-testing program and for the in-house development and standardization of new diagnostic tests. Mycology Proficiency Testing Program provides technical expertise to NYSDOH Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP). The program is responsible for conducting the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-compliant Proficiency Testing (Mycology) for clinical laboratories in New York State. All analytes for these test events are prepared and standardized internally. -

Fungal Infections

FUNGAL INFECTIONS SUPERFICIAL MYCOSES DEEP MYCOSES MIXED MYCOSES • Subcutaneous mycoses : important infections • Mycologists and clinicians • Common tropical subcutaneous mycoses • Signs, symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapy • Identify the causative agent • Adequate treatment Clinical classification of Mycoses CUTANEOUS SUBCUTANEOUS OPPORTUNISTIC SYSTEMIC Superficial Chromoblastomycosis Aspergillosis Aspergillosis mycoses Sporotrichosis Candidosis Blastomycosis Tinea Mycetoma Cryptococcosis Candidosis Piedra (eumycotic) Geotrichosis Coccidioidomycosis Candidosis Phaeohyphomycosis Dermatophytosis Zygomycosis Histoplasmosis Fusariosis Cryptococcosis Trichosporonosis Geotrichosis Paracoccidioidomyc osis Zygomycosis Fusariosis Trichosporonosis Sporotrichosis • Deep / subcutaneous mycosis • Sporothrix schenckii • Saprophytic , I.P. : 8-30 days • Geographical distribution Clinical varieties (Sporotrichosis) Cutaneous • Lymphangitic or Pulmonary lymphocutaneous Renal Systemic • Fixed or endemic Bone • Mycetoma like Joint • Cellulitic Meninges Lymphangitic form (Sporotrichosis) • Commonest • Exposed sites • Dermal nodule pustule ulcer sporotrichotic chancre) (Sporotrichosis) (Sporotrichosis) • Draining lymphatic inflamed & swollen • Multiple nodules along lymphatics • New nodules - every few (Sporotrichosis) days • Thin purulent discharge • Chronic - regional lymph nodes swollen - break down • Primary lesion may heal spontaneously • General health - may not be affected (Sporotrichosis) (Sporotrichosis) Fixed/Endemic variety (Sporotrichosis) • -

P2248 the Incidence and Prevalence of Serious Fungal Infections in Paraguay Gloria Aguilar1, David W

P2248 The incidence and prevalence of serious fungal infections in Paraguay Gloria Aguilar1, David W. Denning*2, Gladys Estigarribia, Carmen Fernandez3 1 Universidad Nacional de Caaguazu, 2 University Hospital of South Manchester, United Kingdom, 3 Board Members IDP Interest Group EAACI Background: Paraguay is home to several endemic fungal diseases as well as modest numbers of HIV positive people, TB cases and many adults with asthma. The burden of fungal diseases in Paraguay has yet to be estimated. Materials/methods: Data on specific populations were obtained from national and international data registries. Prevalence of certain fungal disease was calculated based on epidemiological studies from the region or country. These estimates were informed by our clinical experience in this relatively small country. Results: In 2017, the population of Paraguay was 6,953,646 (50% female) and 2,086,093 (30%) were younger than 15 years. The overall burden of fungal infections was 134,207 (1,930/100 000). The majority of the cases with serious fungal infections were recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis. Assuming a 6% rate of the disease, CCC women were infected with Candida spp. (3,145 /100 000 women). Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and severe asthma with fungal sensitisation (SAFS), were estimated to be 7,788 and 10,280, respectively. Similarly, chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) was estimated to follow tuberculosis in 428 patients based on 2016 data, probably 50% of the total (856). The number of candidemia cases in Paraguay is unknown, so conservatively estimated at 5/100,000 (348 cases) and invasive aspergillosis at 560cases (8/100,000) , In AIDS, cryptococcal meningitis cases were based on Rajasingham et al (2017) and disseminated histoplasmosis in 49 cases based on Adenis et al, 2018. -

Davis Overview of Fungi and Diseases 2014

JHH ID Tutorials Dr Josh Davis December 2014 MYCOLOGY OVERVIEW 1. OVERVIEW. It is estimated that there are 1.5 million extant species of fungi on Earth, of which 60,000 have been described/named; of these only approximately 400 species have ever been described to cause disease in humans and only approximately 20 do so with any frequency. Many others are plant pathogens or symbionts. At least 13,500 fungal species form lichens, symbiotic partnerships between fungi (usually ascomycota) and photosynthetic microbes (eg. algae, cyanobacteria). 2. CLASSIFICATION. There are several confusing/overlapping classifications systems for fungi. 2.1 Biological Kingdom FUNGI; Phyla: 2.1.1 Phylum Zygomycota – Agents of zygomycosis, “mucormycosis”. Most primitive fungi. Broad, ribbon-like hyphae, no septae. Generally grow fast on agar (“lid-lifters”). 2.1.1.1 Order Mucorales – eg. Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Saskanaea, Cuninghamella 2.1.1.2 Order Entomophthorales – Basidiobolus, Canidiobolus 2.1.2 Phylum Basidiomycota – Mushrooms, jelly fungi, smuts, rusts, stinkhorns . and the teleomorph of cryptococcus! 2.1.3 Phylum Ascomycota – e.g. Pseudoallescheria, Curvularia, Saccharomyces. 2.1.4 Phylum Deuteromycota, or Fungi Imperfecti. Not a true phylum. Contains asexual (“imperfect”) forms of fungi (anamorphs), most of which have not had a sexual form described. Most human pathogens are in this group – eg: Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus, Scedosporium, Alternaria, Trichophyton, Cladosporium etc. etc. 1. Sporotrix at 37 and 25 degrees; 2. Aspergillus fumigatus, niger, terreus, flavus (L to R); 3. Candida albicans 2.2 Morphological 2.2.1 Broad classification - Yeasts, Moulds and Dimorphic Fungi 2.2.1.1 Yeasts are single-celled organisms which reproduce by budding and grow as smooth colonies on agar. -

Fungal Group Fungal Disease Source Guidelines Relevant Articles

Fungal Fungal disease Source Guidelines Relevant articles Group ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: 1. Developing European guidelines in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases 2. Diagnostic procedures 3. Non-neutropenic adult patients 4. Prevention and management of Candida diseases ESCMID invasive infections in neonates and children caused by Candida spp 5. Adults with haematological malignancies and after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) 6. Patients with HIV infection or AIDS Candidaemia and IDSA clinical practice guidelines 2016 IDSA invasive candidiasis ISPD ISPD guidelines/recommendations Candida peritonitis Peritoneal Dialysis international article Invasive IDSA clinical practice guidelines 2010 IDSA WHO WHO management guidelines Guidelines for the prevention and Cryptococcal treatment of opportunistic infections in AIDSinfo meningitis HIV-infected Adults and adolescents Southern Guideline for the prevention, African diagnosis and management of HIV cryptococcal meningitis among HIV- clinicians infection persons: 2013 update society IDSA IDSA Clinical practice guidelines 2007 Histoplasmosis Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in disseminated AIDSinfo HIV-infected Adults and adolescents IDSA IDSA Clinical practice guidelines 2007 Histoplasmosis Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in acute pulmonary AIDSinfo HIV-infected Adults and adolescents Invasive IDSA IDSA Clinical practice guidelines 2008 aspergillosis -

Endemic Chromoblastomycosis Caused Predominantly By

Endemic Chromoblastomycosis Caused Predominantly by Fonsecaea nubica, Madagascar1 Tahinamandranto Rasamoelina, Danièle Maubon, Malalaniaina Andrianarison, Irina Ranaivo, Fandresena Sendrasoa, Njary Rakotozandrindrainy, Fetra A. Rakotomalala, Sébastien Bailly, Benja Rakotonirina, Abel Andriantsimahavandy, Fahafahantsoa R. Rabenja, Mala Rakoto Andrianarivelo, Muriel Cornet, Lala S. Ramarozatovo Chromoblastomycosis is an implantation fungal infec- plant material from thorns or wood splinters or by soil tion. Twenty years ago, Madagascar was recognized as contamination of an existing wound (1,2). The causative the leading focus of this disease. We recruited patients agents are mainly Fonsecaea spp., Cladophialophora spp., in Madagascar who had chronic subcutaneous lesions and Rhinocladiella spp. However, rare cases caused by suggestive of dermatomycosis during March 2013– other genera, such as Phialophora spp. or Exophiala spp., June 2017. Chromoblastomycosis was diagnosed in 50 have been reported (1,3). As is the case for other implan- (33.8%) of 148 patients. The highest prevalence was in tation mycoses, chromoblastomycosis lesions are locat- northeastern (1.47 cases/100,000 persons) and southern ed mainly on the lower limbs, particularly on the dorsal (0.8 cases/100,000 persons) Madagascar. Patients with face of the feet, ankles, and legs (1,4–6). chromoblastomycosis were older (47.9 years) than those Infection is caused by a lack of protective clothing without (37.5 years) (p = 0.0005). Chromoblastomyco- or shoes for persons working in rural areas in which sis was 3 times more likely to consist of leg lesions (p = 0.003). Molecular analysis identifiedFonsecaea nubica spiny plants are common. Chromoblastomycosis is in 23 cases and Cladophialophora carrionii in 7 cases.