'Iconic Green' Pre-Planning and Design Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Resource In- Vventory Update for R Monroe Township Y

EnvironmentalENVIRONMENTAL ResourceR RESOURCE In - vventoryINVENTORYyUp Update UPDATE for f FOR200 6 MonroeMonroe TownshipT owns h i p MONROE TOWNSHIP MIDDLESEX COUNTY,2006 NEW JERSEY Monroe TownshipT Prepared by p 20066 ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY UPDATE FOR 2006 MONROE TOWNSHIP MIDDLESEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Historic Plan Element Reference study by Richard Grubb and Associates Geology and Hydrogeology Element Prepared by Environmental Commission member Karen C. Polidoro, Hydrogeologist Scenic Resources Element Prepared by Environmental Commission Heyer, Gruel & Associates, PA Community Planning Consultants 63 Church Street, 2nd Floor New Brunswick, NJ 08901 732-828-2200 Paul Gleitz, P.P. #5802, AICP Aditi Mantrawadi, Associate Planner Acknowledgements MONROE TOWNSHIP Richard Pucci, Mayor Wayne Hamilton, Business Administrator MONROE TOWNSHIP COUNCIL Gerald W. Tamburro, Council President Henry L. Miller, Concil Vice-President Joanne M. Connolly, Councilwoman Leslie Koppel-Egierd, Councilwoman Irwin Nalitt, Concilman ENVIRONMENTAL COMMISSION John L. Riggs, Chairman Leo Beck Priscilla Brown Ed Leonard Karen C. Polidoro Jay Brown Kenneth Konya Andrea Ryan Lee A. Dauphinee, Health Officer Sharon White, Secretary DEDICATION Joseph Montanti 1950-2006 Joe Montanti’s enthusiasm and wisdom were an inspiration to all those who knew him. His vision of Monroe was beautiful and this Environmental Resource Inventory is an effort to make that vision a reality. Joe will be missed by all those who knew him. This Environmental Resource Inventory is -

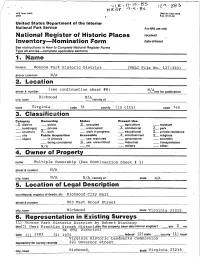

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

.. NPS Form 10·900 0MB No, 1024-0018 (J.82) I Exp, 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Snventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Monroe Park"Historic District (VHLC File No. 127-383) -------- ------~------~---~'----=-~- and or common N/A 2. 11.ocatmon (see continuation sheet #8) street & number N / Ano! for publication Richmond city, town N / Avicinity of state Virginia code 51 county ( in city) code 760 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use -1L district _public _x_ occupied _ agriculture _museum _ building(s) _private _ unoccupied _._X_ commercial Lpark _ structure L both _ work in progress _ educational x__ private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _x_ entertainment x.._ religious _object _ in process _ yes: restricted _ government _ scientific _ being considered Jl_ yes: unrestricted _ Industrial _ transportation N/A _no _ military _other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership Csee Continuation Sheet # 1) street & number N/A city, town N/A N,i'A_ vicinity of state t:1./A 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Richmond City Hall street&number 900 East Broad Street city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 6. Representation in Existing Surveys (1) Monroe Park Historic District by Robert Winthrop title( 2) West Franklin Street Historicllas this property been determined eligible? _ yes K_ no. ~1q7.1. District) . date ( 1) 19 .s 3 C2 I 19 7 2 _ federal W state _ county LU 1oca1 --~~~-~---~~~~VIrginia Historic Landmarks Commission depository for survey records 221 Governor Street --------------- city, town Richmond, state Virginia 23219 7. -

Architectural Reconnaissance Survey, GNSA, SAAM, and BBHW

ARCHITECTURAL RECONNAISSANCE Rͳ11 SURVEY, GNSA, SAAM, AND BBHW SEGMENTS ΈSEGMENTS 15, 16, AND 20Ή D.C. TO RICHMOND SOUTHEAST HIGH SPEED RAIL October 2016 Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond by Caitlin C. Sylvester and Heather D. Staton Prepared for Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation 600 E. Main Street, Suite 2102 Richmond, Virginia 23219 Prepared by DC2RVA Project Team 801 E. Main Street, Suite 1000 Richmond, Virginia 23219 October 2016 October 24, 2016 Kerri S. Barile, Principal Investigator Date ABSTRACT Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), on behalf of the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), conducted a reconnaissance-level architectural survey of the Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/ Hospital Wye (BBHW) segments of the Washington, D.C. to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail (DC2RVA) project. The proposed Project is being completed under the auspices of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) in conjunction with DRPT. Because of FRA’s involvement, the undertaking is required to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. -

Mayor Jones, VCU, Monroe Park Conservancy Announce Successful Completion of Private Fundraising Renovation to Begin in November

Mayor Jones, VCU, Monroe Park Conservancy Announce Successful Completion of Private Fundraising Renovation to Begin in November Richmond, VA., September 21, 2016: Mayor Dwight Jones, Virginia Commonwealth University, and the Monroe Park Conservancy today announced completion of a multi-year campaign to raise $3 million in private funds to renovate Richmond’s oldest city park. The an- nouncement sets in motion procedural steps to allow construction to begin later this year. “Many of us have labored for more than a decade to launch the renovation of Richmond’s oldest park,” said Alice Massie, president of the Monroe Park Conservancy. “I’m grateful to the Mayor, VCU, and the many generous Richmonders who have brought us to this moment. It’s exciting to know that the work can now begin.” Under a 30-year lease agreement that City Council approved unanimously in March 2014, the non-profit Monroe Park Conservancy will operate the park following the City’s completion of the renovation. The Conservancy will steward the park in a partnership agreement with the city, ensuring that it remains a public park with access for all. This is a common practice nation- ally, including Central Park in New York and Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia. Richmond’s Maymont Park operates through a similar arrangement. “The Monroe Park Conservancy has done a great job in securing extensive private support to invest in Richmond’s most historic city park,” said Mayor Jones. “It’s time to put shovels in the ground and begin bringing this beautiful park back to life.” “VCU loves Monroe Park so much that we named our main academic campus for it,” said VCU President Michael Rao. -

Virginia Commonwealth University Area LGBTQ History Walking Tour

Virginia Commonwealth University Area LGBTQ History Walking Tour Many significant events associated with Richmond’s LGBTQ past occurred on or near the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University. The seven sites on this tour include LGBTQ-associated places dating from the Victorian period to the late twentieth century. The route covers 1.25 miles and takes approximately 40 minutes to complete a full circuit. For more information on these and other topics related to Virginia’s LGBTQ history, please visit our website: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/survey-planning/lgbtq-heritage-in-virginia/ A Dignity USA, Richmond Chapter, 16 N. Laurel Street The local chapter of the pro-LGBTQ rights Catholic organization Dignity USA began at this address in 1989. Only steps from the neighboring Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, the chapter was not permitted to meet on Catholic property following a 1986 Vatican Letter banning groups opposed to the church teachings. B Fan Free Clinic, 1103 Floyd Avenue The First Unitarian Universalist Church opened the Fan Free Clinic in 1970. While the clinic initially focused on women’s health, the Fan Free Clinic later became a primary clinic for HIV/AIDS care. The clinic continues to serve local LGBTQ residents today. C Kenneth Pederson Residence, 1100 Block of Grove Avenue VCU Alumni Kenneth Pederson, who lived on the 1100 block of Grove, led the local chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in the early 1970s. Organized in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Inn Riots in New York, the Richmond branch of the Gay Liberation Front passed out leaflets aimed at destigmatizing same-sexuality and organized several events at nearby LGBTQ-friendly establishments. -

Read the Fall 2015 Newsletter

FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NEWS FROM FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NONPROFIT ORG. 412 South Cherry Street U.S. POSTAGE Richmond, Virginia 23220 PAID PERMIT NO. 671 23232 A Gateway Into History WWW.HOLLYWOODCEMETERY.ORG FALL 2015 • VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2 Transformitive Projects 2015 Signature Initiatives at Hollywood Cemetery number of signature projects will mark 2015 as a banner year for Hollywood Cemetery Aand Friends of Hollywood. These include the dedication of a completely restored Palmer fence, the undertaking of an historic genealogy/digitization project, and groundbreaking for a first scenic overlook beside the James River. Palmer Fence Restoration of the Palmer Fence in Presidents Circle was one of the first and most ambitious projects identified by Friends in 2009. The fence dates to Members of the Board of the Anne Carter and Walter R. Robins, Jr. Foundation (left to right): John O’Grady, Hilary Smith, Rita Smith, and Fred Carleton the mid 19th Century and is named for the family plot that it surrounds. Created in the rinceau style (from the French meaning “foliage”), it is one of the most ornate cast iron fences in Richmond. For years, the fence suffered from weather, tree damage, and because of its proximity to Presidents Circle roadways, encounters with vehicles of every size. Presidents Circle has been closed to vehicles for several decades. (continued on page 2) Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 8 Page 10 Wilfred E. ALS Walking President Toney Donors Cutshaw Tour Monroe’s and “Birdcage” Jarrell Fall Colors at Hollywood (Courtesy of Kriss Wilson) (continued from page 1) Miss Sally Adamson Taylor Mr. -

Virginia Commonwealth University Commencement Program Virginia Commonwealth University

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass VCU Commencement Programs VCU University Archives 1971 Virginia Commonwealth University Commencement Program Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/vcucommence © Virginia Commonwealth University Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/vcucommence/4 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the VCU University Archives at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in VCU Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commencement Cxerci6e6 FOR. The Academic Division OF VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITY RICHMOND, VIRGINIA The 1l1osque Auditorium June 6, 1971 10 :00 A.M. and 2 :00 P.M. 0 Norn: The Commencement program schedule<l for 2 :00 p.m. will be found on page 25. PROGRAM for 10:00 A.M. Presiding Dr. Warren W. Brandt President Virginia Commonwealth University Processional* "Festal Flourish," Gordon Jacob "Trumpet Tune in G Major," David N. Johnson "Trumpet Tune in C Major," David N. Johnson Dr. Ardyth Lohuis, Organist Invocation The Reverend Harold W allof Pastor, Presbyterian Campus Ministry Commencement Address Mr. John Joseph Akar Former Ambassador to the United States from Sierra Leone Conferring of Degrees President Warren W. Brandt Dean J. Edwin Whitesell Dean Richard Lodge School of Arts and Sciences School of Social Work Dean Arnold Fleshood Mr. John Ankeney, Director School of Education Division of Engineering Technology Benediction The Reverend Harold Wallo£ Reeiessional "Epilogue," Healey Willan FACULTY MARSHALS: JUNIOR MARSHALS: Dr. Howard G. Ball Marlene Benedetti Dr. John C. Birmingham, Jr. -

Agenda There Will Be a City Council Study Session Meeting on Monday

Agenda St Clair Shores City Council Study Session Monday January pm Jefferson Circle Drive St Clair Shores M There will be a City Council Study Session Meeting on Monday January at pm in the Municipal Building Jefferson Circle Drive St Clair Shores Michigan The agenda will be as follows Call to Order Roll Call and Pledge of Allegiance Audience Participation on agenda items minute time limit Submit form to City Clerk prior to start of meeting Review of Overnight Parking Ordinance Review of Snow Event Ordinance Review of Commercial ParkingSignage concerns Blight Enforcement Procedures Park Grants PoliceFire Millage City Manager Search Audience Participation Individuals with disabilities or impairments who plan to attend this meeting need to contact the City Clerksoffice at or via Michigan Relay Center at ftom TTY if auxiliary aides or services are needed Anyone requesting items to be placed on the agenda must submit the request in writing to the City Clerk days prior to the meeting Published Council Study Session Meeting January AGENDA ITEM Review of Overnight Parking Ordinance Background Approximately parking permits in ENCLOSURES Yearly Overnight on Street Parking Permits Prepared by Lt Lambert Date January YElfE FtERlifi SEE llf PFRfIlllS aPPLYtNG FR PERf at a to accommodate l Perrnits are issued only when there is not enoetih stace residence vehicles reisfered fo that addeess They are not issued for convenience reasons Vehicles with permits must be iri use and must be moved at feast every hours ermits are not issued for commercial vehicles -

Billboard, August 25, 1900

LLBO AT!, SATURDAY, AUGUST 25, 1900, THE BILLBOARD while sitting in a cozy corner in the Lakeside Root,Beer, Coca Cola. Tacked for Dr. Pep- Club, he put his hand up his sleeve and Old Posters. per, Lenox Soap. Have tacked 500 Joker ban- handed me this one: "A shoemaker, whilst ners, 80u* Durham cards, Harter's banners, pegging away at his work, was stared in the It is most unfortunate that so very few of and others. Laredo's population is 14,000; it face day by day with a 28-sheet Beeman's the earliest bills should' have come down to is beautifully situated on the Rio Grande, , Posters' |Gum poster until he could close his eyes and w.ith an iron bridge spanning the river, con- us, for they would have been most curious see those heads reaching for miles and miles, and instructive documents. But, when we necting the two Laredos. Laredo, Mex., has and at night did he dream of it. In the day think of it, it is almost impossible that such a population of 12,000. We have the Mexican Department * at his work did he labor to the rythm of National Machine Shops, which give employ^ should have survived. Once the play was 'Chew Beeman's Gum, chew Beeman's Gum," over, their use was over; they were certain ment to from 300 to BOO men, and we have the until at last he bought some and used it as to be thrown away, or, if brought home, garrison at Fort Mclntosh, which is beauti- wax on his thread." would be lost or torn up. -

Approved Summer Meal Sites, New York, 2019

Approved Summer Meal Sites, New York, 2019 Site County Site Name Site Status Site Address Site City Site Zip Sponsoring Organization Start Date End Date Albany Abrookin Voc & Tech Ctr Open 99 Kent St Albany 12206 Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/01/19 Albany Albany Leadership Charter HS-Girls Open 19 Hackett Blvd Albany 12208 Albany Leadership Charter HS-Girls 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Arbor Hill Community Center Open 47 N Lark St Albany 12210 Albany Housing Authority 07/08/19 08/15/19 Albany Arbor Hill Elementary School Open 1 Arbor Dr Albany 12207 Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Creighton Storey Homes Open 158 Third Ave Albany 12204 Albany Housing Authority 07/01/19 08/23/19 Albany Eagle Point Elementary School Open 1044 Western Ave Albany 12203 Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Edmund J O'Neal MS Of Excellence Open 50 N Lark Ave Albany 12210 Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/09/19 Albany Ezra Prentice Homes Open 625 S Pearl St Albany 12202 Albany Housing Authority 07/01/19 08/23/19 Albany Frank Chapman Memorial Inst Open 340 First St Albany 12206 Albany Housing Authority 07/08/19 08/09/19 Albany Giffen Memorial Elementary School Open 274 S Pearl St Albany 12202 Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Green Tech High Charter School Open 99 Slingerland St Albany 12202 Green Tech High Charter School 07/08/19 08/29/19 Albany Hoffman Park Open 7 Hoffman Ave Albany 12209 Albany Housing Authority 07/01/19 08/23/19 Albany Jc Club Open 63 Quail Street Albany 12206 Victory Christian Church 07/08/19 08/30/19 Albany Metropolitan New Testament -

2019-Sites-That-Operated.Pdf

Sites that Operated in 2019 County Name Site Name Site Status Site Address Site City Site Zip Contact First Name Contact Last Name Contact Phone Email Address Sponsoring Organization Start Date End Date Albany Hoffman Park Open 7 Hoffman Ave Albany 12209 Brigitte Pryor 518-641-7509 [email protected] Albany Housing Authority 07/01/19 08/23/19 Albany William S Hackett Middle School Open 45 Delaware Ave Albany 12202-1301 Stephanie Primero 518-475-6025 [email protected] Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/14/19 Albany Refugee & Immigrant Support Services Closed Enrolled in Needy Area 715 Morris St Albany 12208 Rifat Filkins 518-621-1041 [email protected] Refugee & Immigrant Support Services 07/09/19 08/16/19 Albany Giffen Memorial Elementary School Open 274 S Pearl St Albany 12202-1899 Stephanie Primero 518-475-6025 [email protected] Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Trinity Inst - Homer Perkins Ctr Open 15 Trinity Pl Albany 12202 Brigitte Pryor 518-641-7509 [email protected] Albany Housing Authority 07/08/19 08/16/19 Albany Robert Whalen Homes Open 295 Colonie St Albany 12210 Brigitte Pryor 518-641-7509 [email protected] Albany Housing Authority 07/01/19 08/23/19 Albany Kidz Club Discovery Center Closed Enrolled in Needy Area 172 N Allen St Albany 12206 Elvira Ford 518-629-4017 [email protected] Boys & Girls Club Of Troy 07/01/19 09/05/19 Albany Abrookin Voc & Tech Ctr Open 99 Kent St Albany 12206 Stephanie Primero 518-475-6025 [email protected] Albany City SD 07/08/19 08/01/19 Albany Ezra Prentice -

£&\/ 'Tfhz Buam, J/Jr+L

THE EVENING STAR B-3 to Fairfax School MARYLANDyiRGINIA College Washington, D C. ** U. S. Acts Acquire NEWS Park 11, IDftH WEDNESDAY. JULY Standards Bureau Site JBr : mHHHi Study Includes Road Opening By G. O. HERNDON Severest Critic Communist Issue Raised Set for Monday The Federal Government moved today acquire 550-acre to a The Fairfax County School site for a S4O million Bureau of Standards installation on the A new dual lane highway which outskirts of Gaithersburg in Montgomery County. Board has decided to put one Again in Maryland Race will divert traffic from the Uni- (new The site is bounded by Washington National pike Route of its severest critics on a com- » versity of Maryland campus will 240', (Cloppers road', Maryland’s race today picked up College.. State Route 117 State Route 124 (Quince mittee studying possible reor- senatorial where it left off be dedicated at Park Orchard road' and Muddy Branch road. six years ago with hints of the Communist issue being raised again Monday. ' ganization of the education sys- Location of the tract is about 18 miles from downtown Opening fall campaign salvoes were exchanged by Republican The State Roads Commission Washington Senator and about 5 miles tem. Butler and the man he defeated in 1950, former Senator said today that Gov. McKeldin south of where the new Atomic; struction of the new facility. The board last night named Millard E. Tydings, Democrat. will cut the traditional ribbons a Energy Commission headquarters Congress and the President In blast reminiscent of his earlier successful campaign at the be Harley Williams, president of western end of the new will built.