View the Site History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form I

NPS Form lWOl 1% Isso) United States Deparbnent of the Interior National Park Service . NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This fwm is for use in Minating or requesting determinations for indMdual properties and dislricts. See iMmmrin How to Comght me Nabonal Remrol MsWc Places Re@sbzh Fom (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "I(' in the appmpriate box a by entering the information requested. If any item docs not apply to the proparty tming documented, enter "NIA" for "nd applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of s@Wemce,enter only categwk and subcategories fmm the inrtrudhs. Place addiiional entries and namtiv. item on continuation sheets (NPS Fwm 1m). Use a wer,word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Monroe Ward other nameslsite number ~Mo st0 ' . ' 2. Location street & number Mam imd Carv ~(ree~sfromnnth to soh. 3rd to ~(ree~sh & to west not for publicatjon~ city or town Richmond vicinity NIA state VA code county code - zip code 23219 3. Stateffederal Agency Certification I I As the designated auth* under the National Hlstork Presmatii Act of 1986, as amended. I hereby mWy that this. minination request for daMminath of aligibillty me& the h.docurfmtation standards for registering propadlea in thc N-l Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and profeasbnal mquiramants sat fodh in 38 CFR Part 69. In my opinion, the prW maetr does not meet tha National Regidor CrlleAa. Irecommend the4 this pmpefty be considered dgnlfkant C] nationalty stacwidc. laally. ( C] SM dnuation sheet for addltklgl comments.) State w Federal agency and bumau I I In my opinion, the prom meats h nd the Natland Regwcrlter!a. -

Environmental Resource In- Vventory Update for R Monroe Township Y

EnvironmentalENVIRONMENTAL ResourceR RESOURCE In - vventoryINVENTORYyUp Update UPDATE for f FOR200 6 MonroeMonroe TownshipT owns h i p MONROE TOWNSHIP MIDDLESEX COUNTY,2006 NEW JERSEY Monroe TownshipT Prepared by p 20066 ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY UPDATE FOR 2006 MONROE TOWNSHIP MIDDLESEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Historic Plan Element Reference study by Richard Grubb and Associates Geology and Hydrogeology Element Prepared by Environmental Commission member Karen C. Polidoro, Hydrogeologist Scenic Resources Element Prepared by Environmental Commission Heyer, Gruel & Associates, PA Community Planning Consultants 63 Church Street, 2nd Floor New Brunswick, NJ 08901 732-828-2200 Paul Gleitz, P.P. #5802, AICP Aditi Mantrawadi, Associate Planner Acknowledgements MONROE TOWNSHIP Richard Pucci, Mayor Wayne Hamilton, Business Administrator MONROE TOWNSHIP COUNCIL Gerald W. Tamburro, Council President Henry L. Miller, Concil Vice-President Joanne M. Connolly, Councilwoman Leslie Koppel-Egierd, Councilwoman Irwin Nalitt, Concilman ENVIRONMENTAL COMMISSION John L. Riggs, Chairman Leo Beck Priscilla Brown Ed Leonard Karen C. Polidoro Jay Brown Kenneth Konya Andrea Ryan Lee A. Dauphinee, Health Officer Sharon White, Secretary DEDICATION Joseph Montanti 1950-2006 Joe Montanti’s enthusiasm and wisdom were an inspiration to all those who knew him. His vision of Monroe was beautiful and this Environmental Resource Inventory is an effort to make that vision a reality. Joe will be missed by all those who knew him. This Environmental Resource Inventory is -

General Photograph Collection Index-Richmond Related Updated 10/3/14

THE VALENTINE General Photograph Collection Richmond-related Subjects The Valentine’s Archives hold one million photographs that document people, places, and events in Richmond and Virginia. This document is an index of the major Richmond- related subject headings of the Valentine’s General Photograph Collection. Photographs in this collection date from the late 19th century until the present and are arranged by subject. Additional major subjects in the General Photograph Collection include: • Civil War • Cook Portrait Collection – Portraits of famous Virginians • Museum Collection – Museum objects and buildings • Virginia Buildings and Places The Valentine also has the following additional photograph collections: • Small Photograph Collection – Prints 3”x5” and under • Oversized Photograph Collection – Large and panoramic prints • Cased Image Collection – 400+ daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, and framed photographs • Stereograph Collection – 150+ views of Richmond, Virginia and the Civil War • Over 40 individual photograph collections – Including those of Robert A. Lancaster, Jr., Palmer Gray, Mary Wingfield Scott, Edith Shelton, and the Colonial Dementi Studio. Please inquire by email ([email protected]), fax (804-643-3510), or mail (The Valentine, Attn: Archives, 1015 E. Clay Street, Richmond, VA 23219) to schedule a research appointment, order a photograph, or to obtain more information about photographs in the Valentine’s collection. Church Picnic in Bon Air, 1880s Cook Collection, The Valentine Page 1 of 22 The Valentine -

St.Catherine's

fall 2008 vol. 67 no. 1 st.catherine’snow inside: The Essence of St. Catherine’s Spirit Fest Highlights Alumnae and Parent Authors 1 Blair Beebe Smith ’83 came to St. Catherine’s from Chicago as a 15-year-old boarding student with a legacy connection - her mother, Caroline Short Beebe ’55 - and the knowledge that her great-grand- father had relatives in town. “I didn’t know a soul,” said Blair, today a Richmond resident and kitchen designer with Heritage Woodworks. A younger sister – Anne Beebe ’85 – shortly followed her to St. Catherine’s, and today Blair maintains a connection with her alma mater through her own daughters – junior Sarah and freshman Blair Beebe Smith ’83 Peyton. Her son Harvard is a 6th grader at St. Christopher’s. Blair recently shared her memories of living for two years on Bacot II: Boarding Memories2 The Skirt Requirement “Because we had to Williams Hotel “We had our permission slips signed wear skirts to dinner, we threw on whatever we could find. and ready to go for overnights at Sarah Williams’ house. It didn’t matter if it was clean or dirty, whether it matched Sarah regularly had 2, 3, 4 or more of us at the ‘Williams the rest of our outfit or not…the uglier, the better.” Hotel.’ It was great.” Doing Laundry “I learned from my friends how Dorm Supervisors “Most of our dorm supervi- to do laundry (in the basement of Bacot). I threw every- sors were pretty nice. I was great friends with Damon thing in at once, and as a result my jeans turned all my Herkness and Kim Cobbs.” white turtlenecks blue. -

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

.. NPS Form 10·900 0MB No, 1024-0018 (J.82) I Exp, 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Snventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Monroe Park"Historic District (VHLC File No. 127-383) -------- ------~------~---~'----=-~- and or common N/A 2. 11.ocatmon (see continuation sheet #8) street & number N / Ano! for publication Richmond city, town N / Avicinity of state Virginia code 51 county ( in city) code 760 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use -1L district _public _x_ occupied _ agriculture _museum _ building(s) _private _ unoccupied _._X_ commercial Lpark _ structure L both _ work in progress _ educational x__ private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _x_ entertainment x.._ religious _object _ in process _ yes: restricted _ government _ scientific _ being considered Jl_ yes: unrestricted _ Industrial _ transportation N/A _no _ military _other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership Csee Continuation Sheet # 1) street & number N/A city, town N/A N,i'A_ vicinity of state t:1./A 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Richmond City Hall street&number 900 East Broad Street city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 6. Representation in Existing Surveys (1) Monroe Park Historic District by Robert Winthrop title( 2) West Franklin Street Historicllas this property been determined eligible? _ yes K_ no. ~1q7.1. District) . date ( 1) 19 .s 3 C2 I 19 7 2 _ federal W state _ county LU 1oca1 --~~~-~---~~~~VIrginia Historic Landmarks Commission depository for survey records 221 Governor Street --------------- city, town Richmond, state Virginia 23219 7. -

Historical Documentation of the Site of Venture Richmond's Proposed

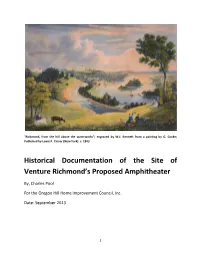

"Richmond, from the hill above the waterworks"; engraved by W.J. Bennett from a painting by G. Cooke; Published by Lewis P. Clover (New York) c. 1843 Historical Documentation of the Site of Venture Richmond’s Proposed Amphitheater By, Charles Pool For the Oregon Hill Home Improvement Council, Inc. Date: September 2013 1 Table of Contents: Introduction ………………………………..………………………………………………………………Page 3 The historic site …………………………………………………………………………………………..Page 6 Venture Richmond’s amphitheater proposal ………….…………………………………Page 10 Canal tow path historically 30 feet wide at this site ………..…………………………Page 13 Canal water elevation at 83 feet from 1840 ……………………………..……………….Page 19 Tow path at least two feet above water level in canal ……………..……………….Page 24 Canal 60 feet wide from 1838 ……………..……………………………………………………Page 27 Canal is a carefully engineered, impermeable structure …………………….……..Page 32 Sacrifice of slaves and immigrants ……………………………..……………………………..Page 36 Archaeological resources on the proposed amphitheater site ………………..…Page 38 Railroad tracks connecting Tredegar with Belle Isle ……………….………………….Page 44 Tredegar wall (anticipatory demolition?) ……………….………………………………..Page 49 Oregon Hill associations with the canal ………….………………………………………..Page 51 Zoning considerations ……………………………………………………………………………….Page 55 Plans for re-watering the James River and Kanawha Canal ……………………….Page 57 Alternative site for Venture Richmond’s largest stage ……………………………….Page 59 Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………..Page 60 2 (Figure 1.) View of Richmond from Hollywood Cemetery, (detail) 1854 (Source: Library of Virginia) The James River and Kanawha Canal provided vital transportation and water power for the development of Richmond. Introduction: It has been said that Richmond possesses such an embarrassment of historical riches that they are not fully appreciated. This is the case with the James River and Kanawha Canal, which is of profound importance nationally as one of the first canals in the nation with locks. -

'Iconic Green' Pre-Planning and Design Study

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone Projects Urban and Regional Studies and Planning 2021 VCU Monroe Park Campus 'Iconic Green' Pre-Planning and Design Study Nicholas A. Jancaitis Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/murp_capstone Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Landscape Architecture Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Social Justice Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/murp_capstone/38 This Professional Plan Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Regional Studies and Planning at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VCU Monroe Park Campus 'Iconic Green' Pre-Planning and Design Study Prepared for: VCU Facilities Management, Planning and Design Prepared by: Nicholas Anthony Jancaitis, CPT, PLA In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Master of Urban and Regional Planning in the VCU Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs Virginia Commonwealth University May 2021 COPYRIGHT © 2021 BY NICHOLAS JANCAITIS VCU Monroe Park Campus 'Iconic Green' Pre-Planning and Design Study James Smither, -

Architectural Reconnaissance Survey, GNSA, SAAM, and BBHW

ARCHITECTURAL RECONNAISSANCE Rͳ11 SURVEY, GNSA, SAAM, AND BBHW SEGMENTS ΈSEGMENTS 15, 16, AND 20Ή D.C. TO RICHMOND SOUTHEAST HIGH SPEED RAIL October 2016 Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond by Caitlin C. Sylvester and Heather D. Staton Prepared for Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation 600 E. Main Street, Suite 2102 Richmond, Virginia 23219 Prepared by DC2RVA Project Team 801 E. Main Street, Suite 1000 Richmond, Virginia 23219 October 2016 October 24, 2016 Kerri S. Barile, Principal Investigator Date ABSTRACT Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), on behalf of the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), conducted a reconnaissance-level architectural survey of the Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/ Hospital Wye (BBHW) segments of the Washington, D.C. to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail (DC2RVA) project. The proposed Project is being completed under the auspices of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) in conjunction with DRPT. Because of FRA’s involvement, the undertaking is required to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. -

Mayor Jones, VCU, Monroe Park Conservancy Announce Successful Completion of Private Fundraising Renovation to Begin in November

Mayor Jones, VCU, Monroe Park Conservancy Announce Successful Completion of Private Fundraising Renovation to Begin in November Richmond, VA., September 21, 2016: Mayor Dwight Jones, Virginia Commonwealth University, and the Monroe Park Conservancy today announced completion of a multi-year campaign to raise $3 million in private funds to renovate Richmond’s oldest city park. The an- nouncement sets in motion procedural steps to allow construction to begin later this year. “Many of us have labored for more than a decade to launch the renovation of Richmond’s oldest park,” said Alice Massie, president of the Monroe Park Conservancy. “I’m grateful to the Mayor, VCU, and the many generous Richmonders who have brought us to this moment. It’s exciting to know that the work can now begin.” Under a 30-year lease agreement that City Council approved unanimously in March 2014, the non-profit Monroe Park Conservancy will operate the park following the City’s completion of the renovation. The Conservancy will steward the park in a partnership agreement with the city, ensuring that it remains a public park with access for all. This is a common practice nation- ally, including Central Park in New York and Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia. Richmond’s Maymont Park operates through a similar arrangement. “The Monroe Park Conservancy has done a great job in securing extensive private support to invest in Richmond’s most historic city park,” said Mayor Jones. “It’s time to put shovels in the ground and begin bringing this beautiful park back to life.” “VCU loves Monroe Park so much that we named our main academic campus for it,” said VCU President Michael Rao. -

Virginia Commonwealth University Area LGBTQ History Walking Tour

Virginia Commonwealth University Area LGBTQ History Walking Tour Many significant events associated with Richmond’s LGBTQ past occurred on or near the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University. The seven sites on this tour include LGBTQ-associated places dating from the Victorian period to the late twentieth century. The route covers 1.25 miles and takes approximately 40 minutes to complete a full circuit. For more information on these and other topics related to Virginia’s LGBTQ history, please visit our website: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/survey-planning/lgbtq-heritage-in-virginia/ A Dignity USA, Richmond Chapter, 16 N. Laurel Street The local chapter of the pro-LGBTQ rights Catholic organization Dignity USA began at this address in 1989. Only steps from the neighboring Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, the chapter was not permitted to meet on Catholic property following a 1986 Vatican Letter banning groups opposed to the church teachings. B Fan Free Clinic, 1103 Floyd Avenue The First Unitarian Universalist Church opened the Fan Free Clinic in 1970. While the clinic initially focused on women’s health, the Fan Free Clinic later became a primary clinic for HIV/AIDS care. The clinic continues to serve local LGBTQ residents today. C Kenneth Pederson Residence, 1100 Block of Grove Avenue VCU Alumni Kenneth Pederson, who lived on the 1100 block of Grove, led the local chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in the early 1970s. Organized in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Inn Riots in New York, the Richmond branch of the Gay Liberation Front passed out leaflets aimed at destigmatizing same-sexuality and organized several events at nearby LGBTQ-friendly establishments. -

Read the Fall 2015 Newsletter

FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NEWS FROM FRIENDS OF HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY NONPROFIT ORG. 412 South Cherry Street U.S. POSTAGE Richmond, Virginia 23220 PAID PERMIT NO. 671 23232 A Gateway Into History WWW.HOLLYWOODCEMETERY.ORG FALL 2015 • VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2 Transformitive Projects 2015 Signature Initiatives at Hollywood Cemetery number of signature projects will mark 2015 as a banner year for Hollywood Cemetery Aand Friends of Hollywood. These include the dedication of a completely restored Palmer fence, the undertaking of an historic genealogy/digitization project, and groundbreaking for a first scenic overlook beside the James River. Palmer Fence Restoration of the Palmer Fence in Presidents Circle was one of the first and most ambitious projects identified by Friends in 2009. The fence dates to Members of the Board of the Anne Carter and Walter R. Robins, Jr. Foundation (left to right): John O’Grady, Hilary Smith, Rita Smith, and Fred Carleton the mid 19th Century and is named for the family plot that it surrounds. Created in the rinceau style (from the French meaning “foliage”), it is one of the most ornate cast iron fences in Richmond. For years, the fence suffered from weather, tree damage, and because of its proximity to Presidents Circle roadways, encounters with vehicles of every size. Presidents Circle has been closed to vehicles for several decades. (continued on page 2) Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 8 Page 10 Wilfred E. ALS Walking President Toney Donors Cutshaw Tour Monroe’s and “Birdcage” Jarrell Fall Colors at Hollywood (Courtesy of Kriss Wilson) (continued from page 1) Miss Sally Adamson Taylor Mr. -

Appendix A: Housing Needs and Market Assessment

Appendix A: Housing Needs and Market Assessment City of Richmond, Virginia November 6, 2014 Appendix A: Housing Needs and Market Assessment PREPARED FOR: Economic Development and Planning City of Richmond, Virginia 900 East Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23219 PREPARED BY: David Paul Rosen & Associates 1330 Broadway, Suite 937 Oakland, CA 94612 510-451-2552 510-451-2554 Fax [email protected] www.draconsultants.com 3941 Hendrix Street Irvine, CA 92614 949-559-5650 949-559-5706 Fax [email protected] www.draconsultants.com Fin City of Richmond Target Area Market Conditions Analysis November 6, 2014 FinaFina Table of Contents A. Introduction ........................................................................... 1 B. Definition of Affordable Housing: Income Levels, Rents and Home Prices .................................................................... 2 1. Target Income Levels .................................................................... 2 2. Affordable Rents and Home Prices ................................................ 3 a. Affordable Housing Cost Definitions ......................................... 3 b. Occupancy Standards ............................................................... 3 c. Utility Allowances .................................................................... 4 d. Affordable Rents and Sales Prices ............................................. 4 C. Summary of Existing Housing Needs ...................................... 6 1. Household Income Distribution ...................................................