Vampire Movies Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is One of the Only Scary Stories That Actually Scared Me

"This is one of the only scary stories that actually scared me. This is quite a long book, so I decided to make it in 5 parts. The next 15 questions will come out soon! Test your memory and see how much you remember." 1. Chapter 1: Jonathan Harker's Journal-Where is Mr. Harker travelling to in the beginning of the novel? Budapest Borgo Pass Bucharest Bistritz 2. True or false: When Harker arrived at the lodge, he received a note from Count Dracula himself. True False 3. The horses were driven by "a tall man with a long brown beard." At first what was the only part of his face that Harker could see? his teeth his nose his ears his eyes 4. We now arrive at Dracula's castle. The door is answered by "a tall old man, clean shaven save for a long white moustache, and clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere." What was it about this man that reminded Harker of the carriage driver? his ears his eyes his grip his teeth 5. A couple of nights later, Harker can't sleep much, so he decides to shave. He is startled by Count Dracula due to the fact that he could not see his reflection in the mirror. At the time he was startled, he cut his chin with the razor. How did Dracula react when he saw the blood? He did nothing He tried to hypnotize him He made a grab for his throat He moved slowly toward him 6. -

Copyrighted Material

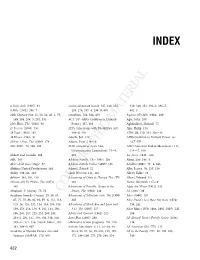

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert (History) COURSE FORMAT The course content and assessment components (discussion forums, examinations) are fully delivered online. COURSE OVERVIEW & GOALS Everyone's heard of “Dracula” and knows who he was (or is!), right? Well ... While it's true that “Dracula” — aka “Vlad III Dracula” and “Vlad the Impaler” — are household words throughout the planet, surprisingly few have any detailed comprehension of his life and times, or comprehend how and why this particular historical figure came to be the most celebrated vampire in history. Throughout this class we'll track those themes, and our guiding aims will be to understand: (1) “what exactly happened” in the course of Dracula's life, and three reigns as prince (voivode) of Wallachia (1448; 1456-62; 1476); (2) how serious historians can (and sometimes cannot!) uncover and interpret the life and career of “The Impaler” on the basis of surviving narratives, documents, pictures, and monuments; (3) how and why contemporaries of Vlad Dracula launched a project of vilifying his character and deeds, in the early decades of the printed book; (4) to what extent Vlad Dracula was known and remembered from the late 15th century down to the 1890s, when Bram Stoker was writing his famous novel ultimately entitled Dracula; (5) how, and with what sources, Stoker constructed his version of Dracula, and why this image became and remains the standard popular notion of Dracula throughout the world; and (6) how Dracula evolved as an icon of 20th century popular culture, particularly in the media of film and the novel. -

A Retrospective Diagnosis of RM Renfield in Bram Stoker's Dracula

Journal of Dracula Studies Volume 12 Article 3 2010 All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Elizabeth Winter Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Winter, Elizabeth (2010) "All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula," Journal of Dracula Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dracula Studies by an authorized editor of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected],. All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Cover Page Footnote Elizabeth Winter is a psychiatrist in private practice in Baltimore, MD. Dr. Winter is on the adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins where she lectures on anxiety disorders and supervises psychiatry residents. This article is available in Journal of Dracula Studies: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol12/ iss1/3 All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Elizabeth Winter [Elizabeth Winter is a psychiatrist in private practice in Baltimore, MD. Dr. Winter is on the adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins where she lectures on anxiety disorders and supervises psychiatry residents.] In late nineteenth century psychiatry, there was little consistency in definition or classification criteria of mental illness. -

Making Sense of Mina: Stoker's Vampirization of the Victorian Woman in Dracula Kathryn Boyd Trinity University

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity English Honors Theses English Department 5-2014 Making Sense of Mina: Stoker's Vampirization of the Victorian Woman in Dracula Kathryn Boyd Trinity University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Kathryn, "Making Sense of Mina: Stoker's Vampirization of the Victorian Woman in Dracula" (2014). English Honors Theses. 20. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_honors/20 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Despite its gothic trappings and origin in sensationalist fiction, Bram Stoker's Dracula, written in 1897, is a novel that looks forward. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Britons found themselves in a world of new possibilities and new perils –in a society rapidly advancing through imperialist explorations and scientific discoveries while attempting to cling to traditional institutions, men and woman struggled to make sense of the new cultural order. The genre of invasion literature, speaking to the fear of Victorian society becoming tainted by the influence of some creeping foreign Other, proliferated at the turn of the century, and Stoker's threatening depictions of the Transylvanian Count Dracula resonated with his readers. Stoker’s text has continued to resonate with readers, as further social and scientific developments in our modern world allow more and more opportunities to read allegories into the text. -

Bram Stoker's Dracula

Danièle André, Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Film Journal / 5 / Screening the Supernatural / 2019 / pp. 62-74 Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Danièle André University of La Rochelle, France Dracula, that master of masks, can be read as the counterpart to the Victorian society that judges people by appearances. They both belong to the realm of shadows in so far as what they show is but deception, a shadow that seems to be the reality but that is in fact cast on a wall, a modern version of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Dracula rules over the world of representation, be it one of images or tales; he can only live if people believe in him and if light is not thrown on the illusion he has created. Victorian society is trickier: it is the kingdom of light, for it is the time when electric light was invented, a technological era in which appearances are not circumscribed by darkness but are masters of the day. It is precisely when the light is on that shadows can be cast and illusions can appear. Dracula’s ability to change appearances and play with artificiality (electric light and moving images) enhances the illusions created by his contemporaries in the late 19th Century. Through the supernatural atmosphere of his 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Francis Ford Coppola thus underlines the deep links between cinema and a society dominated by both science and illusion. And because cinema is both a diegetic and extra-diegetic actor, the 62 Danièle André, Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Film Journal / 5 / Screening the Supernatural / 2019 / pp. -

SLAV-T230 Vampire F2019 Syllabus-Holdeman-Final

The Vampire in European and American Culture Dr. Jeff Holdeman SLAV-T230 11498 (SLAV) (please call me Jeff) SLAV-T230 11893 (HHC section) GISB East 4041 Fall 2019 812-855-5891 (office) TR 4:00–5:15 pm Office hours: Classroom: GA 0009 * Tues. and Thur. 2:45–3:45 pm in GISB 4041 carries CASE A&H, GCC; GenEd A&H, WC * and by appointment (just ask!!!) * e-mail me beforehand to reserve a time * It is always best to schedule an appointment. [email protected] [my preferred method] 812-335-9868 (home) This syllabus is available in alternative formats upon request. Overview The vampire is one of the most popular and enduring images in the world, giving rise to hundreds of monster movies around the globe every year, not to mention novels, short stories, plays, TV shows, and commercial merchandise. Yet the Western vampire image that we know from the film, television, and literature of today is very different from its eastern European progenitor. Nina Auerbach has said that "every age creates the vampire that it needs." In this course we will explore the eastern European origins of the vampire, similar entities in other cultures that predate them, and how the vampire in its look, nature, vulnerabilities, and threat has changed over the centuries. This approach will provide us with the means to learn about the geography, village and urban cultures, traditional social structure, and religions of eastern Europe; the nature and manifestations of Evil and the concept of Limited Good; physical, temporal, and societal boundaries and ritual passage that accompany them; and major historical and intellectual periods (the settlement of Europe, the Age of Reason, Romanticism, Neo-classicism, the Enlightenment, the Victorian era, up to today). -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

The Elizabeth Bathory Story

Nar. umjet. 46/1, 2009, pp. 133-159, L. Kürti, The Symbolic Construction of the Monstruous… Original scientific paper Received: 2nd Jan. 2009 Accepted: 15th Feb. 2009 UDK 392.28:291.13] LÁSZLÓ KÜRTI University of Miskolc, Miskolc THE SYMBOLIC CONSTRUCTION OF THE MONSTROUS – THE ELIZABETH BATHORY STORY This article analyzes several kinds of monsters in western popular culture today: werewolves, vampires, morlaks, the blood-countess and other creatures of the underworld. By utilizing the notion of the monstrous, it seeks to return to the most fundamental misconception of ethnocentrism: the prevailing nodes of western superiority in which tropes seem to satisfy curiosities and fantasies of citizens who should know better but in fact they do not. The monstrous became staples in western popular cultural production and not only there if we take into account the extremely fashionable Japanese and Chinese vampire and werewolf fantasy genre as well. In the history of East European monstrosities, the story of Countess Elizabeth Bathory has a prominent place. Proclaimed to be the most prolific murderess of mankind, she is accused of torturing young virgins, tearing the flesh from their living bodies with her teeth and bathing in their blood in her quest for eternal youth. The rise and popularity of the Blood Countess (Blutgräfin), one of the most famous of all historical vampires, is described in detail. In the concluding section, examples are provided how biology also uses vampirism and the monstrous in taxonomy and classification. Key words: scholarship; monstrosity; vampirism; blood-countess; Elizabeth Bathory There are several kinds of monsters in western popular culture today: werewolves, vampires, morlaks, the blood-countess and other creatures of the underworld. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

National Conference

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION In Memoriam We honor those members who passed away this last year: Mortimer W. Gamble V Mary Elizabeth “Mery-et” Lescher Martin J. Manning Douglas A. Noverr NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE POPULAR CULTURE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CULTURE ASSOCIATION APRIL 15–18, 2020 Philadelphia Marriott Downtown Philadelphia, PA Lynn Bartholome Executive Director Gloria Pizaña Executive Assistant Robin Hershkowitz Graduate Assistant Bowling Green State University Sandhiya John Editor, Wiley © 2020 Popular Culture Association Additional information about the PCA available at pcaaca.org. Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................................................................ 8 Registration and Check-In ............................................................................11 Exhibitors ..........................................................................................................12 Special Meetings and Events .........................................................................13 Area Chairs ......................................................................................................23 Leadership.........................................................................................................36 PCA Endowment ............................................................................................39 Bartholome Award Honoree: Gary Hoppenstand...................................42 Ray and Pat Browne Award