The Negril Tourism Industry: Growth, Challenges and Future Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phony Colonee These Motels Contained Colonial- Themed Architecture, Featuring Red Brick Facades, Cupolas Or Turret Crowned Roofs

n the eyes of some, it is as tacky as a plastic pink flamingo on a front lawn in a trailer park. To others, it is a fun, if idealized, throwback to a better Itime. However you view it, there is no doubt it is one of the Garden State’s somewhat underappreciated influences on the world of architecture. Known as Doo-Wop, it found a unique expression that came of age along with a generation of New Jerseyans in the motels of Wildwoods. The Wildwoods You wouldn’t know it to look at it today, but New Jersey’s Wildwoods were once, indeed, a tangle of wild woods. They sit on a six mile long barrier island near the southern tip of the state at Exit 4 on the Garden State Parkway. When one says “The Wildwoods,” they refer collectively to three separate municipalities: North Wildwood, Wildwood, and Wildwood Crest. They were founded by developers between 1880 and 1905, notably including Frederick Swope and his Five Mile Beach Improvement Company, Philip Pontius Baker and his Wildwood Beach Improvement Company, and John Burk with the Holly Beach Improvement Company. All saw the It might be hard to believe now, but The Wildwoods are named island’s potential in terms of the ideal summer resort, or “Cottage Colony.” after woods that were indeed The small fishing village of Anglesea was the first to be founded in 1880, wild. Note the tree in the followed by Wildwood in 1890. In 1906, Anglesea was then repackaged as foreground bent to grow into a letter “W”! the island’s first specifically resort town and renamed North Wildwood. -

Three Perfect Days

No matter how many passport stamps you’ve collected, visiting Costa Rica presents a challenge. What seems so small and straightforward on paper—a traveler-friendly nation that’s dwarfed by West Virginia—feels larger than life once you’re on the ground. The seas on either side are separated by rugged mountain ranges, complete with fire-spitting volcanoes and mist-shrouded cloud forests. And the country’s dozen or so distinct ecological zones— which are heavily protected and together account for 5 percent of the world’s biodiversity, including jaguars, sloths, and more than 1,200 species of butterfly—are also home to an abundance of microclimates, each of which has little regard for your plans. It excites the imagination, but also forces hard decisions: Absorb the culture of bustling San José, spy on treetop monkeys on Volcán Arenal, or dive into the cobalt-blue Pacific on Guanacaste’s Gold Coast? You’ll be in a rush to do it all, but remember to slow down. It’s only then that you’ll discover the state of being known as pura Three vida—the true source of Costa Rica’s wealth. Perfect Days Costa Rica By Peter Koch Photography by Matthew Johnson 56 57 56-69_HEMI1019_3PD_3_R1.indd 56 06/09/2019 10:11 56-69_HEMI1019_3PD_3_R1.indd 57 06/09/2019 10:11 DAY 11,260-foot-tall volcano, loom- original intent was to give all with embroidered first com- ing over the skyline. San José is Costa Ricans access to high- munion dresses, Technicolor perched at 3,845 feet above sea brow culture; admission was floral displays, and growers of level, in the mountain-fringed just one colón. -

Report Template Normal Planning Appeal

Inspector’s Report 300440-17 Development The construction of a single storey discount foodstore (to include off licence use). The development includes the erection of signage. The proposed development will be served by 112 no. car parking spaces with vehicular/pedestrian access will be provided from the Strand Road. The proposed development includes the construction of a single storey ESB sub station, lighting, all landscaping, boundary treatment and site development works. Location Strand Road, Tramore, County Waterford. Planning Authority Waterford City and County Council. Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 17/697. Applicant Aldi Stores Ltd. Type of Application Permission. Planning Authority Decision Refusal of permission. ABP300440-17 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 35 Type of Appeal First Party Appellant Aldi Stores Ltd. Observer Leefield Ltd. Date of Site Inspection 21st August 2018. Inspector Derek Daly. ABP300440-17 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 35 1.0 Site Location and Description 1.1. The appeal site is within the built up area of the town of Tramore in relative close proximity to both the town centre and the beachfront. The site is currently vacant with no active use on the site. 1.2. The site has a stated area of 1.02 hectares and is irregular in configuration. The site has road frontage onto Strand Road to the south and southwest. The site also incorporates a roadway off Strand Road referred to as Crescent Road which loops in a semi circular manner around the rear of a number of properties fronting onto Strand Road. This roadway provides access for the site. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Ideology and Utopia Along the Backpacker Trail

Responsibly Engaged: Ideology and Utopia along the Backpacker Trail By Sonja Bohn Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology (2012) Abstract By following the backpacker trail beyond the „tourist bubble,‟ travellers invest in the ideals of freedom, engagement, and responsibility. Backpacker discourse foregrounds travellers‟ freedom to mobility as it constructs the world as „tourable‟; engagement is demonstrated in the search for „authentic‟ connections with cultural Others, beyond the reach of globalised capitalism; responsibility is shouldered by yearning to improve the lives of these Others, through capitalist development. While backpackers frequently question the attainability of these ideals, aspiring to them reveals a desire for a world that is open, diverse, and egalitarian. My perspective is framed by Fredric Jameson‟s reading of the interrelated concepts of ideology and utopia. While backpacker discourse functions ideologically to reify and obscure global inequalities, to entrench free market capitalism, and to limit the imagining of alternatives, it also figures for a utopian world in which such ideology is not necessary. Using this approach, I attempt to undertake critique of backpacker ideology without invalidating its utopian content, while seeking to reveal its limits. Overall, I suggest that late- capitalism subsumes utopian desires for a better way of living by presenting itself as the solution. This leaves backpackers feeling stranded, seeking to escape the ills of capitalism, via capitalism. ii Acknowledgements I am grateful to the backpackers who generously shared their travel stories and reflections for the purposes of this research, I wish you well on your future journeys. -

New England Vacations

NewBest England Vacations 1 NEW ENGLAND TODAY Index Things to Do in Boston Classic Boston Attractions..........................................................................................2 Explore Beacon Hill........................................................................................................3 Explore Swan Boats........................................................................................................4 Maine Vacations The 5 Best Photo Ops in Acadia National Park.....................................................6 10 Prettiest Coastal Towns In Maine........................................................................7 Where to Spot Moose in Maine...................................................................................8 Best of Mount Desert Island.........................................................................................8 Explore York Beach, Maine.........................................................................................10 Things to Do in New Hampshire Best Classic Attractions in New Hampshire......................................................12 Best of the White Mountains...................................................................................13 Best of the NH Seacoast.............................................................................................14 Best Scenic Hikes in the White Mountains.........................................................16 Explore Mt. Washington Cog Railroad.................................................................17 -

Review of Winnipeg Beach: Leisure and Courtship in a Resort Town, 1900-1967

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Great Plains Studies, Center for Social Sciences Spring 2012 Review of Winnipeg Beach: Leisure and Courtship in a Resort Town, 1900-1967. By Dale Barbour. Pauline Greenhill University of Winnipeg, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Geography Commons Greenhill, Pauline, "Review of Winnipeg Beach: Leisure and Courtship in a Resort Town, 1900-1967. By Dale Barbour." (2012). Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 1221. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch/1221 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Book Reviews 89 Winnipeg Beach: Leisure and Courtship in a Resort Town, 1900-1967. By Dale Barbour. Winnipeg: University of Mani toba Press, 201 I. xiii + 211 pp. Photographs, maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index. C$24.95 paper. The back cover designates this book as "history," but, like the best social history, it offers much to a broad range of other disciplines, including women's and gender studies, cultural geography, folklore, and cultural studies. Though modest in size and aims, Winnipeg Beach is a superb example of how a scholar fascinated with everyday life can link it with broader social movements. -

Resort Morphology: Chinese Applications

Resort Morphology: Chinese Applications by Jia Liu A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2008 ©Jia Liu 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55535-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55535-4 NOTICE: VIS The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author’s permission. -

Recessions and Resorts: How Macroeconomic Decline Affects Ski Resort Economies

RECESSIONS AND RESORTS: HOW MACROECONOMIC DECLINE AFFECTS SKI RESORT ECONOMIES A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Beryl Elizabeth Coulter May 2016 RECESSIONS AND RESORTS: HOW ECONOMIC DECLINE AFFECTS SKI RESORT ECONOMIES Beryl Elizabeth Coulter May 2016 Economics Abstract This thesis is a study of the economies of ski resort towns before, during, and after economic recessions, in particular the Great Recession of the U.S. Ski resort towns often have limited (and relatively expensive) housing, which threatens these economics because of the heavy reliance on a large service-based workforce. This study compares small ski resort towns and rural non-resort towns using median home values as the dependent variable. The data was analyzed using ordinary least squares regression. This study aims determine how the housing situation in resort communities changes during times of economic decline and times of economic growth. KEYWORDS: resort, recession, ski, housing, home value, service industry, luxury good, unemployment, OLS, affordable home price JEL CODES: D01, J11, J21, P25, R30, R31 ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Beryl Elizabeth Coulter 3 February 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my thesis advisor, College Research Professor Kevin Rask, for his help gathering data, teaching econometrics, and assisting me with the entire thesis-writing process. Thank you to my academic advisor, Professor Esther Redmount, for teaching me basic economic theory and guiding me through academic decisions during my time at Colorado College. -

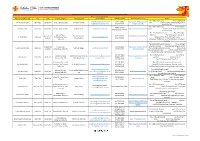

List-Of-Transiting-Hotels.Pdf

TRANSITING HOTELS FOR RETURNING OVERSEAS FILIPINOS (ROFs) and BALIKBAYANS (As 21 of September 2021) Name of Establishment City Type Complete Address Contact Person Email Address Mobile Number Online Booking Portal Rates Php 1,888, Single room Php 2,688, Double [email protected]/ 09054772382/ http://www.facebook.com/F Felicity Island Hotel Lapu-Lapu Quarantine Basak, Lapu-Lapu City Honeylou Amores room with full boardt, additional Php 800 for [email protected] 09323640737 elicityIslandHotel airport transfers Php 1,800, single room, Php 2,500 twin 09178217154/ Dulcinea Hotel Lapu-Lapu Quarantine Pusok, Lapu-Lapu City Rowela Aguro [email protected] http://www.dulcineahotel.ph room, all rates include fullboard meals and 09064722628/ 495.2741 airport transfers Php 1500/night (superior) Php 1750 /night Queens Road, (deluxe) Php 1950/night (Deluxe plus) Quarantine/ Gieselle Abinales/ 09177107863/ https://www.stmarkhotel.ph St. Mark Hotel Cebu City Redemptorist Plaza, [email protected] Additional Php 750 for full board meals; Isolation Eunice Cadavis 09177294132 / Cebu City additional Php 800 (car) and Php 1500 (van) for airport transfers Php 2,100/night (Single), Standard Php 2,700/night (double), Standard Php 2,400/night (Single), Deluxe Quarantine/ N. Escario St. 032.520.2222/ http://www.facebook.com/e Escario Central Hotel Cebu City Merry An Alegre [email protected] Php 3,000/ngiht (double), Deluxe Rates include Isolation Kamputhaw, Cebu City 09177169981 scariocentralhotel full-board packed meals Airport Transfer (one-way): Php 900 (car), Php 1200 (Innova), Php 1500 (van) 032.402.5999/ Php 3,100.00 (single) Php 4,000.00 Archbishop Reyes Kristal Manalang-Catarroja/ cebuallreservation@questhotelsa https://questhotelsandresort Quest Hotel Cebu City Multi-Use 09989615734/ (double) Full board meals Avenue, Cebu City Mariel Daug-daug ndresorts.com s.com/cebu/ 09174017844 Php 750.00/way airport transfers #6 Junquera Ext cor R.R. -

Kona Seaside Hotel

FOR SALE KONA SEASIDE HOTEL FEE SIMPLE INTEREST 75-5646 Kuakini Highway | Kailua-Kona, Big Island of Hawaii INVESTMENT INFORMATION INVESTMENT SUMMARY PURCHASE PRICE: $23,000,000 NAME: Kona Seaside Hotel ADDRESS: 75-5646 Kuakini Highway Kailua-Kona, HI 96740 OWNER/GROUND LESSOR: Lanihau Properties, LLC LAND AREA: 62,726 sq. ft. BUILDING AREA: 53,472 sq. ft. TMK: (3) 7-5-6: 16 # OF ROOMS: 125 # OF FLOORS: 6 ZONING: V-75 Resort Hotel LEASE EXPIRATION: September 30, 2022 KONA SEASIDE HOTEL KONA 2020 LEASE RATES: $133,200 HOTEL IMPROVEMENTS REVERT TO FEE OWNER IN 2022 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS » Fee simple opportunity with income stream in-place » High visibility & convenient access » Improvements in good condition » Rare opportunity to reposition a fee simple Hawaii hotel » Strategic location on main access Palani Road in Kailua-Kona, near Kailua Bay with endless waterfront activities » Across from the recently sold Courtyard Marriott - King Kamehameha Hotel » Upside potential to increase income through renovation and increases in nightly rental rates » Located in a high density community neighborhood area with a lot of tourist traffic » Among the residential and resort trade area with high income demographics 2 KONA SEASIDE HOTEL KONA Kona Seaside Hotel is a landmark hotel situated in the center of Kailua Town on the Big Island of Hawaii. Its prime Kailua-Kona location offers easy access to Kailua Bay scuba diving, parasailing, and paddleboarding or pristine snorkeling in the bay. The 125-room main hotel and building offers a lovely retreat in Hawaiian paradise. 3 PROPERTY INFORMATION Once the playground of Hawaiian royalty, Kailua-Kona is rich with culture, historical stories and said to be the most spiritual of all Hawaiian Islands. -

Coastal Resort Morphology As a Response to Transportation Technology

Coastal Resort Morphology as a Response to Transportation Technology by Haryann T. Brent A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 1997 @ M.T. Brent 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Weliington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada YwfiYe votre réifërena Our irre Nam rdWrgnCe The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la foxme de microfiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. The University of Waterloo requires the signatures of al1 persons using or photocopying this thesis. Pleaae sign below and give address and date. iii Coastal Resort Morphology as a Response to Transportation Technology Abstract The primary goal of the thesis has been a comparison of heyday at three coastal resorts of the eastern United States.