Vancouver Island Marmot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

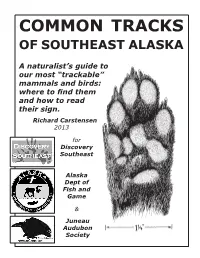

Common Tracks of Southeast Alaska

COMMON TRACKS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA A naturalist’s guide to our most “trackable” mammals and birds: where to find them and how to read their sign. Richard Carstensen 2013 for Discovery Southeast Alaska Dept of Fish and Game & Juneau Audubon Society TRACKING HABITATS muddy beaches stream yards & trails mudflat banks buildings keen’s mouse* red-backed vole* long-tailed vole* red squirrel beaver porcupine shrews* snowshoe hare* black-tailed deer domestic dog house cat black bear short-t. weasel* mink marten* river otter * Light-footed. Tracks usually found only on snow. ISBN: 978-0-9853474-0-6# 2013 text & illustrations © Discovery Southeast Printed by Alaska Litho Juneau, Alaska 1 CONTENTS DISCOVERY SOUTHEAST ........................................................... 2 ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME ............................... 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION ............................................ 5 TRACKING BASICS: LINGO, GAITS ......................................... 10 SCIENTIFIC NAMES ................................................................ 16 MAMMAL TRACK DESCRIPTIONS ............................................ 18 BIRD TRACK DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 35 AMPHIBIANS .......................................................................... 40 OTHER MAMMALS ................................................................... 41 OTHER BIRDS ......................................................................... 45 RECOMMENDED FIELD -

Montana Owl Workshop

MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 LEADER: DENVER HOLT LIST COMPILED BY: DENVER HOLT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 By Denver Holt The winter of 2021 was relatively mild, with only one big storm in October and one cold snap in February. In fact, Great Horned Owls began nesting at the onset of this cold snap. Our female at the ORI field station began laying eggs and incubating. For almost a week the temperature dropped from about 20 degrees F to 10, then 0, then minus 10, minus 15, and eventually minus 28 degrees below zero. Meanwhile, the male roosted nearby and provided his mate with food while she incubated eggs. Eventually, the pair raised three young to fledging. Our group was able to see the entire family. By late February to early March, an influx of Short-eared Owls occurred. I had never seen anything like it. Hundreds of Short-eared Owls arrived in the valley. Flocks of 15, 20, 35, 50, and 70 were regularly reported by ranchers, birders, photographers, and others. And, in one evening I counted 90, of which 73 were roosting on fence posts and counted at one time. By mid-to-late March, however, except for Great Horned Owls, other owl species numbers dropped significantly. We found only one individual Long-eared Owl and zero nests in our Missoula study site. It’s been many, many years since we have not found a nest in Missoula. -

Fur Color Diversity in Marmots

Ethology Ecology & Evolution 21: 183-194, 2009 Fur color diversity in marmots Kenneth B. ArmitAge Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7534, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) Received 6 September 2008, accepted 19 May 2009 Fur color that differs from the typical shades of brown and gray occurs in eight species of marmots. Albinism generally is rare whereas melanism is more common. Melanism may persist in some populations at low frequencies averaging 16.1% in M. monax and in M. flaviventris for as long as 80 years. White (not albino) and “bluish” marmots generally are rare, but a population of white M. marmota persisted for at least 10 years. Four species are characterized as having pelages of “extreme colors”; M. caudata, red; M. vancouverensis, dark brown; M. caligata, white; M. bai- bacina, gray. Fur is involved in heat transfer between the marmot and its environment. Heat transfer depends on fur structure (fur depth, hair length, density, and diameter), on fur spectral properties (absorptivity, reflectivity), and on the thermal environment (temperature, wind speed, radiation). Heat transfer is highly sensitive to solar radiation. Metabolic rates calculated from the fur model corresponded closely with measured values at ambient temperatures ≤ 20 °C. Solar radiation can either provide heat that could reduce metabolism or thermally stress a marmot. M. fla- viventris orients towards the sun when solar radiation is low and reduces exposure when it is high. Light fur reduces and dark fur color increases absorptivity. I hypothesize that fur color functions primarily in heat trans- fer. -

Wildlife Diversity Brochure

Since 2002, The Wildlife Diversity Program and our partners have conducted projects on over 100 diff erent species of wildlife. The list below spotlights some of the species receiving our att enti on: The Wildlife Diversity Waterbirds Mammals Raptors Amphibians Program Mission: Conserving • yellow-billed loon • wood bison • golden eagle • wood frog • common loon • brown bear, Kenai population • bald eagle • western toad To conserve the natural diversity • Pacifi c loon • Alaska marmot • osprey • rough-skinned newt of Alaska’s wildlife, habitats and Alaska’s • red-necked grebe • hoary marmot • gyrfalcon • northwestern salamander • horned grebe • Montague Island marmot • Queen Charlotte goshawk • long-toed salamander ecosystems. • Glacier Bay marmot • American peregrine falcon Landbirds • collared pika • Arctic peregrine falcon Seabirds Wildlife • American dipper • tundra hare • Peale’s peregrine falcon • short-tailed albatross • rusty blackbird • least weasel • northern saw-whet owl • marbled murrelet • Arctic warbler • little brown myotis • northern pygmy owl • Kittlitz’s murrelet • Aleutian tern Diversity • Prince of Wales spruce grouse • Keen’s myotis • northern hawk owl • olive-sided fl ycatcher • California myotis • western screech owl • black-legged kittiwake • various other songbirds • long-legged myotis • barred owl • common murre • silver-haired bat • short-eared owl • glaucous-winged gull Marine Mammals • various other small mammals • boreal owl • pelagic cormorant • bowhead whale • great gray owl • double-crested cormorant • North -

Hoary Marmot

Alaska Species Ranking System - Hoary marmot Hoary marmot Class: Mammalia Order: Rodentia Marmota caligata Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 17 December 2018 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: IUCN:Least Concern Audubon AK: S Rank: S4 USFWS: BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 -32 Action -40 to 40 4 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -6 Unknown, but suspected large. This species is common in suitable habitat (MacDonald and Cook 2009) and has a relatively large range in Alaska. Range Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -10 Occurs from southeast Alaska north to the Yukon River and from Canada west to Bethel and the eastern Alaska Peninsula (Gunderson et al. 2009; MacDonald and Cook 2009). Absent from nearly all islands in southeast Alaska (MacDonald and Cook 2009), but distribution on islands in southcentral Alaska is unclear (Lance 2002b; L. -

Juneau Wildlife Viewing Guide

W O W ildlife ildlife ur atch All other photos © ADF&G. ADF&G. © photos other All Marmot, deer, downtown and American dipper photos © Jamie Karnik, ADF&G. ADF&G. Karnik, Jamie © photos dipper American and downtown deer, Marmot, adventure and head on out! out! on head and adventure Fish and Game Game and Fish Bear safety, porcupine and beaver photos © A.W. Hanger Hanger A.W. © photos beaver and porcupine safety, Bear your camera, a good pair of shoes and your sense of of sense your and shoes of pair good a camera, your visit wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov visit communities, Alaska Department of of Department Alaska Ready to get started? Juneau’s wildlife is waiting – grab grab – waiting is wildlife Juneau’s started? get to Ready browse through wildlife viewing sites in other other in sites viewing wildlife through browse about the Alaska Coastal Wildlife Viewing Trail, or to to or Trail, Viewing Wildlife Coastal Alaska the about call 586-2201. 586-2201. call www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov FOR MORE INFORMATION INFORMATION MORE FOR the Centennial Hall visitor center or or center visitor Hall Centennial the call 888-581-2201. In Juneau, stop by by stop Juneau, In 888-581-2201. call Skagway and Wrangell. Wrangell. and Skagway providers and employers. employers. and providers or or www.traveljuneau.com Visit Bureau. are equal opportunity opportunity equal are Wales Island, Sitka, Sitka, Island, Wales consult the Juneau Convention & Visitors Visitors & Convention Juneau the consult All public partners partners public All Petersburg, Prince of of Prince Petersburg, For information on tours and lodging, lodging, and tours on information For Restoration Program Program Restoration Juneau, Ketchikan, Ketchikan, Juneau, Wildlife Conservation and and Conservation Wildlife new places on your own. -

Indicators of Individual and Population Health in the Vancouver Island

INDICATORS OF INDIVIDUAL AND POPULATION HEALTH IN THE VANCOUVER ISLAND MARMOT (MARMOTA VANCOUVERENSIS) BY MALCOLM LEE MCADIE D.V.M., Western College of Veterinary Medicine, 1987 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Thompson Rivers University Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada November 2018 Thesis examining committee: Karl Larsen (PhD), Thesis Supervisor, Natural Resource Sciences, Thompson Rivers University Craig Stephen (DVM, PhD), Thesis Supervisor, Executive Director, Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Cooperative David Hill (PhD), Committee Member, Faculty of Arts, Thompson Rivers University Todd Shury (DVM, PhD), External Examiner, Wildlife Health Specialist, Parks Canada ii Thesis Supervisors: Dr. Karl Larsen and Dr. Craig Stephen ABSTRACT The Vancouver Island Marmot (Marmota vancouverensis) is an endangered rodent endemic to the mountains of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Following population declines in the 1980s and 1990s, an intensive captive breeding and reintroduction program was initiated involving three Canadian zoos and a purpose-built, subalpine facility on Vancouver Island. From 1997 to 2017, 660 marmots were associated with the captive program, including 63 wild-born individuals captured for breeding and 597 marmots born and weaned in captivity. Reintroductions began in 2003 and by 2017 a total of 501 marmots had been released. Although this significantly increased the wild population from its low point in 2003, conservation -

Okanogan County Wildlife Species List

Washington Gap Analysis Project 288 Species Predicted or Breeding in: Okanogan County CODE COMMON NAME Amphibians RACAT Bullfrog RALU Columbia spotted frog SPIN Great basin spadefoot AMMA Long-toed salamander PSRE Pacific treefrog (Chorus frog) AMTI Tiger salamander BUBO Western toad Birds REAM American avocet BOLE American bittern FUAM American coot COBR American crow CIME American dipper CATR American goldfinch FASP American kestrel ANRUBE American pipit SERU American redstart TUMI American robin ANAAM American wigeon HALE Bald eagle RIRI Bank swallow HIRU Barn swallow STVA Barred owl BUIS Barrow's goldeneye CEAL Belted kingfisher CYNI Black swift CHNI Black tern PIAR Black-backed woodpecker PIPI Black-billed magpie PAAT Black-capped chickadee ARAL Black-chinned hummingbird PHME Black-headed grosbeak DEOB Blue grouse ANDI Blue-winged teal DOOR Bobolink PAHU Boreal chickadee AEFU Boreal owl EUCY Brewer's blackbird SPBR Brewer's sparrow CEAM Brown creeper MOAT Brown-headed cowbird CACAL California quail STELCA Calliope hummingbird BRCA Canada goose NatureMapping 2007 Washington Gap Analysis Project CATME Canyon wren CACAS Cassin's finch VISO Cassin's vireo (Solitary vireo) BOCE Cedar waxwing PARU Chestnut-backed chickadee SPPA Chipping sparrow ALCH Chukar ANCY Cinnamon teal NUCO Clark's nutcracker HIPY Cliff swallow TYAL Common barn-owl BUCL Common goldeneye GAIM Common loon MERME Common merganser CHMI Common nighthawk PHNU Common poorwill COCOR Common raven GAGA Common snipe GETR Common yellowthroat ACCO Cooper's hawk JUHY Dark-eyed -

Dental Pathology of the Hoary Marmot (Marmota Caligata), Groundhog (Marmota Monax) and Alaska Marmot (Marmota Broweri)

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Dental Pathology of the Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata), Groundhog (Marmota monax) and Alaska Marmot (Marmota broweri). Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8j69r801 Journal Journal of comparative pathology, 156(1) ISSN 0021-9975 Authors Winer, JN Arzi, B Leale, DM et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.1016/j.jcpa.2016.10.005 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California J. Comp. Path. 2016, Vol. -,1e11 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental Pathology of the Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata), Groundhog (Marmota monax) and Alaska Marmot (Marmota broweri) J. N. Winer*, B. Arzi†, D. M. Leale†,P.H.Kass‡ and F. J. M. Verstraete† *William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, † Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA and ‡ Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Summary Museum specimens (maxillae and mandibles) of the three marmot species occurring in Alaska (Marmota caligata [n ¼ 108 specimens], Marmota monax [n ¼ 30] and Marmota broweri [n ¼ 24]) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria. There were 71 specimens (43.8%) from female animals, 69 (42.6%) from male animals and 22 (13.6%) from animals of unknown sex. The ages of animals ranged from neonatal to adult, with 121 young adults (74.4%) and 41 adults (25.3%) included, and 168 excluded from study due to neonatal/ju- venile age or incompleteness of specimens (missing part of the dentition). -

Inventory Methods for Pikas and Sciurids: Pikas, Marmots, Woodchuck, Chipmunks and Squirrels

Inventory Methods for Pikas and Sciurids: Pikas, Marmots, Woodchuck, Chipmunks and Squirrels Standards for Components of British Columbia's Biodiversity No.29 Prepared by Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Resources Inventory Branch for the Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force Resources Inventory Committee December 1, 1998 Version 2.0 © The Province of British Columbia Published by the Resources Inventory Committee Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Inventory methods for pikas and sciurids [computer file] (Standards for components of British Columbia's biodiversity ; no. 29) Previously published: Lindgren, Pontus M.F. Standardized inventory methodologies for components of British Columbia's biodiversity. Pikas and sciurids, 1997. Available through the Internet. Issued also in printed format on demand. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-3727-X 1. Sciuridae - British Columbia - Inventories - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2.Pikas - British Columbia - Inventories - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 3. Rodent populations - British Columbia. 4. Ecological surveys - British Columbia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. Resources Inventory Branch. II. Resources Inventory Committee (Canada). Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force. III. Title: Pikas, marmots, woodchuck, chipmunks and squirrels. IV. Series. QL737.R68I58 1998 333.95'93611'09711 C98-960329-6 Additional Copies of this publication can be purchased from: Superior Repro #200 - 1112 West Pender Street Vancouver, BC V6E 2S1 Tel: (604) 683-2181 Fax: (604) 683-2189 Digital Copies are available on the Internet at: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/ric Biodiversity Inventory Methods for Pikas and Sciurids Preface This manual presents standard methods for inventory of Pikas and Sciurids in British Columbia at three levels of inventory intensity: presence/not detected (possible), relative abundance, and absolute abundance. -

VANCOUVER ISLAND MARMOT Marmota Vancouverensis Original1 Prepared by Andrew A

VANCOUVER ISLAND MARMOT Marmota vancouverensis Original1 prepared by Andrew A. Bryant Species Information not complete their molt every year. For this reason yearlings are typically a uniform faded rusty colour Taxonomy in June and 2 year olds have dark fur. Older animals can take on a decidedly mottled appearance, with The Vancouver Island Marmot, Marmota patches of old, faded fur contrasting with new, vancouverensis (Swarth 1911), is endemic to dark fur. Vancouver Island and is the only member of the Marmots have large, beaver-like incisors, sharp genus Marmota that occurs there (Nagorsen 1987). claws, and very powerful shoulder and leg muscles. Five other species of marmot occur in North Adults typically measure 65–70 cm from nose to tip America: the Woodchuck, M. monax; Hoary of the tail. Weights show large seasonal variation. An Marmot, M. caligata; Yellow-bellied Marmot, adult female that weighs 3 kg when she emerges M. flaviventris; Olympic Marmot, M. olympus; from hibernation in late April can weigh 4.5–5.5 kg and Brower’s Marmot, M. browerii). Worldwide, by the onset of hibernation in mid-September. Adult 14 species are recognized (Barash 1989). males can be even larger, reaching weights of up to Marmota vancouverensis was described from 7 kg. Marmots generally lose about one-third of 12 specimens shot on Douglas Peak and Mount their body mass during winter hibernation. McQuillan in central Vancouver Island in 1910 (Swarth 1912). Marmota vancouverensis is con- Distribution sidered a “true” species on the basis of karyotype Global (Rausch and Rausch 1971), cranial-morphometric characteristics (Hoffman et al.