Fur Color Diversity in Marmots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vancouver Island Marmot

Vancouver Island Marmot Restricted to the mountains of Vancouver Island, this endangered species is one of the rarest animals in North America. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks move between colonies can have a profound one basket” situation puts the Vancouver impact on the entire population. Island Marmot at considerable risk of Vancouver Island Marmots have disap- extinction. peared from about two-thirds of their his- Why are Vancouver Island torical natural range within the past several What is their status? Marmots at risk? decades and their numbers have declined by urveys of known and potential colony he Vancouver Island Marmot exists about 70 percent in the last 10 years. The sites from 1982 through 1986 resulted in nowhere in the world except Vancouver 1998 population consisted of fewer than 100 counts of up to 235 marmots. Counts Island.Low numbers and extremely local- individuals, making this one of the rarest Srepeated from 1994 through 1998 turned Tized distribution put them at risk. Human mammals in North America. Most of the up only 71 to 103 animals in exactly the same activities, bad weather, predators, disease or current population is concentrated on fewer areas. At least 12 colony extinctions have sheer bad luck could drive this unique animal than a dozen mountains in a small area of occurred since the 1980s. Only two new to extinction in the blink of an eye. about 150 square kilometres on southern colonies were identified during the 1990s. For thousands of years, Vancouver Island Vancouver Island. Estimating marmot numbers is an Marmots have been restricted to small Causes of marmot disappearances imprecise science since counts undoubtedly patches of suitable subalpine meadow from northern Vancouver Island remain underestimate true abundance. -

COMMON MAMMALS of OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK Roosevelt Elk the Largest and Most Majestic of All the Animals to Be Found in Olympic Na

COMMON MAMMALS OF OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK Roosevelt Elk The largest and most majestic of all the animals to be found in Olympic National Park is the Roosevelt or Olympic elk. They were given the name Roosevelt elk in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt who did much to help preserve them from extinction. They are also known by the name "wapiti" which was given to them by the Shawnee Indians. Of the two kinds of elk in the Pacific Northwest, the Roosevelt elk are the largest. Next to the moose, the elk is the largest member of the deer family. The male sometimes measures 5 feet high at the shoulder and often weighs 800 pounds or more. Their coats are a tawny color except for the neck which is dark brown. It is easy to tell elk from deer because of the large size and the large buff colored rump patch. When the calves are born in May or June, they weigh between 30 and 40 pounds and are tawny colored splashed with many light spots and a conspicuous rump patch. Only the bull elk has antlers. They may measure as much as 5 feet across. Each year they shed the old set of antlers after mating season in the fall and almost immediately begin to grow a new set. During the summer months, some of the elk herds can be found in the high mountains; the elk move down into the rain forest valleys on the western side of the park during the winter months. About 5,000 elk live in Olympic National Park where they, like all of the animals are protected in their natural environment. -

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

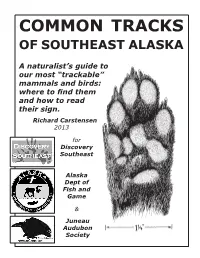

Common Tracks of Southeast Alaska

COMMON TRACKS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA A naturalist’s guide to our most “trackable” mammals and birds: where to find them and how to read their sign. Richard Carstensen 2013 for Discovery Southeast Alaska Dept of Fish and Game & Juneau Audubon Society TRACKING HABITATS muddy beaches stream yards & trails mudflat banks buildings keen’s mouse* red-backed vole* long-tailed vole* red squirrel beaver porcupine shrews* snowshoe hare* black-tailed deer domestic dog house cat black bear short-t. weasel* mink marten* river otter * Light-footed. Tracks usually found only on snow. ISBN: 978-0-9853474-0-6# 2013 text & illustrations © Discovery Southeast Printed by Alaska Litho Juneau, Alaska 1 CONTENTS DISCOVERY SOUTHEAST ........................................................... 2 ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME ............................... 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION ............................................ 5 TRACKING BASICS: LINGO, GAITS ......................................... 10 SCIENTIFIC NAMES ................................................................ 16 MAMMAL TRACK DESCRIPTIONS ............................................ 18 BIRD TRACK DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 35 AMPHIBIANS .......................................................................... 40 OTHER MAMMALS ................................................................... 41 OTHER BIRDS ......................................................................... 45 RECOMMENDED FIELD -

Convergent Evolution of Himalayan Marmot with Some High-Altitude Animals Through ND3 Protein

animals Article Convergent Evolution of Himalayan Marmot with Some High-Altitude Animals through ND3 Protein Ziqiang Bao, Cheng Li, Cheng Guo * and Zuofu Xiang * College of Life Science and Technology, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha 410004, China; [email protected] (Z.B.); [email protected] (C.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (Z.X.); Tel.: +86-731-5623392 (C.G. & Z.X.); Fax: +86-731-5623498 (C.G. & Z.X.) Simple Summary: The Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) lives on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and may display plateau-adapted traits similar to other high-altitude species according to the principle of convergent evolution. We assessed 20 species (marmot group (n = 11), plateau group (n = 8), and Himalayan marmot), and analyzed their sequence of CYTB gene, CYTB protein, and ND3 protein. We found that the ND3 protein of Himalayan marmot plays an important role in adaptation to life on the plateau and would show a history of convergent evolution with other high-altitude animals at the molecular level. Abstract: The Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) mainly lives on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and it adopts multiple strategies to adapt to high-altitude environments. According to the principle of convergent evolution as expressed in genes and traits, the Himalayan marmot might display similar changes to other local species at the molecular level. In this study, we obtained high-quality sequences of the CYTB gene, CYTB protein, ND3 gene, and ND3 protein of representative species (n = 20) from NCBI, and divided them into the marmot group (n = 11), the plateau group (n = 8), and the Himalayan marmot (n = 1). -

Olympic Marmot (Marmota Olympus)

Candidate Species ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Olympic Marmot (Marmota olympus) State Status: Candidate, 2008 Federal Status: None Recovery Plans: None The Olympic marmot is an endemic species, found only in the Olympic Mountains of Washington (Figure 1). It inhabits subalpine and alpine meadows and talus slopes at elevations from 920-1,990 m (Edelman 2003). Its range is largely contained within Olympic National Park. The Olympic marmot was added Figure 1. Olympic marmot (photo by Rod Gilbert). to the state Candidate list in 2008, and was designated the State Endemic Mammal by the Washington State Legislature in 2009. The Olympic marmot differs from the Vancouver Island marmot (M. vancouverensis), in coat color, vocalization, and chromosome number. Olympic marmots were numerous during a 3-year study in the 1960s, but in the late 1990s rangers began noticing many long-occupied meadows no longer hosted marmots. Olympic marmots differ from most rodents by having a drawn out, ‘K-selected’ life history; they are not reproductively mature until 3 years of age, and, on average, females do not have their first litter until 4.5 years of age. Marmots can live into their teens. Data from 250 ear-tagged and 100 radio-marked animals indicated that the species was declining at about 10%/year at still-occupied sites through 2006, when the total population of Olympic marmots was thought to be fewer than 1,000 animals. During 2007-2010, a period of higher snowpack, marmot survival rates improved and numbers at some well-studied colonies stabilized. Human disturbance and disease were ruled out as causes, but the decline was apparently due to low survival of females (Griffin 2007, Griffin et al. -

Montana Owl Workshop

MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 LEADER: DENVER HOLT LIST COMPILED BY: DENVER HOLT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 25–30, 2021 By Denver Holt The winter of 2021 was relatively mild, with only one big storm in October and one cold snap in February. In fact, Great Horned Owls began nesting at the onset of this cold snap. Our female at the ORI field station began laying eggs and incubating. For almost a week the temperature dropped from about 20 degrees F to 10, then 0, then minus 10, minus 15, and eventually minus 28 degrees below zero. Meanwhile, the male roosted nearby and provided his mate with food while she incubated eggs. Eventually, the pair raised three young to fledging. Our group was able to see the entire family. By late February to early March, an influx of Short-eared Owls occurred. I had never seen anything like it. Hundreds of Short-eared Owls arrived in the valley. Flocks of 15, 20, 35, 50, and 70 were regularly reported by ranchers, birders, photographers, and others. And, in one evening I counted 90, of which 73 were roosting on fence posts and counted at one time. By mid-to-late March, however, except for Great Horned Owls, other owl species numbers dropped significantly. We found only one individual Long-eared Owl and zero nests in our Missoula study site. It’s been many, many years since we have not found a nest in Missoula. -

Alarm Calling in Yellow-Bellied Marmots: I

Anim. Behav., 1997, 53, 143–171 Alarm calling in yellow-bellied marmots: I. The meaning of situationally variable alarm calls DANIEL T. BLUMSTEIN & KENNETH B. ARMITAGE Department of Systematics and Ecology, University of Kansas (Received 27 November 1995; initial acceptance 27 January 1996; final acceptance 13 May 1996; MS. number: 7461) Abstract. Yellow-bellied marmots, Marmota flaviventris, were reported to produce qualitatively different alarm calls in response to different predators. To test this claim rigorously, yellow-bellied marmot alarm communication was studied at two study sites in Colorado and at one site in Utah. Natural alarm calls were observed and alarm calls were artificially elicited with trained dogs, a model badger, a radiocontrolled glider and by walking towards marmots. Marmots ‘whistled’, ‘chucked’ and ‘trilled’ in response to alarming stimuli. There was no evidence that either of the three call types, or the acoustic structure of whistles, the most common alarm call, uniquely covaried with predator type. Marmots primarily varied the rate, and potentially a few frequency characteristics, as a function of the risk the caller experienced. Playback experiments were conducted to determine the effects of call type (chucks versus whistles), whistle rate and whistle volume on marmot responsiveness. Playback results suggested that variation in whistle number/rate could communicate variation in risk. No evidence was found of intraspecific variation in the mechanism used to communicate risk: marmots at all study sites produced the same vocalizations and appeared to vary call rate as a function of risk. There was significant individual variation in call structure, but acoustic parameters that were individually variable were not used to communicate variation in risk. -

The Successful Introduction of the Alpine Marmot Marmota Marmota In

JOBNAME: No Job Name PAGE: 1 SESS: 18 OUTPUT: Mon Mar 12 14:45:29 2012 SUM: 8A81CE40 /v2503/blackwell/journals/mam_v0_i0_new_style_2010/mam_212 Mammal Rev. 2012 1 REVIEW 2 3 The successful introduction of the alpine marmot 4 Marmota marmota in the Pyrenees, Iberian Peninsula, 5 Western Europe 6 7 Isabel C. BARRIO* Pyrenean Institute of Ecology, Avda, Regimiento de Galicia s/n 8 PO Box 64, 22700 Jaca (Huesca), Spain, and Department of Biological Sciences, 9 University of Alberta T6G 2E9 Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. 10 E-mail: [email protected] 11 Juan HERRERO Technical School of Huesca, University of Zaragoza, 22071 Huesca, 12 Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 13 C. Guillermo BUENO Pyrenean Institute of Ecology, Avda. Regimiento de Galicia 14 s/n PO Box 64, 22700 Jaca (Huesca), Spain, and Department of Biological Sciences, 15 University of Alberta T6G 2E9 Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. 16 E-mail: [email protected] 17 Bernat C. LÓPEZ Center for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications, 18 Autonomous University of Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain. 19 E-mail: [email protected] 20 Arantza ALDEZABAL Landare-Biologia eta Ekologia Saila, UPV-EHU, PO Box 644, 21 48080 Bilbo, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 22 Ahimsa CAMPOS-ARCEIZ School of Geography, University of Nottingham 23 Malaysian Campus, Semenyih 43,500, Selangor, Malaysia. 24 E-mail: [email protected] 25 Ricardo GARCÍA-GONZÁLEZ Pyrenean Institute of Ecology, Avda. Regimiento de 26 Galicia s/n PO Box 64, 22700 Jaca (Huesca), Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 27 28 29 ABSTRACT 30 1. The introduction of non-native species can pose environmental and economic 31 risks, but under some conditions, introductions can serve conservation or recre- 32 ational objectives. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Wildlife Diversity Brochure

Since 2002, The Wildlife Diversity Program and our partners have conducted projects on over 100 diff erent species of wildlife. The list below spotlights some of the species receiving our att enti on: The Wildlife Diversity Waterbirds Mammals Raptors Amphibians Program Mission: Conserving • yellow-billed loon • wood bison • golden eagle • wood frog • common loon • brown bear, Kenai population • bald eagle • western toad To conserve the natural diversity • Pacifi c loon • Alaska marmot • osprey • rough-skinned newt of Alaska’s wildlife, habitats and Alaska’s • red-necked grebe • hoary marmot • gyrfalcon • northwestern salamander • horned grebe • Montague Island marmot • Queen Charlotte goshawk • long-toed salamander ecosystems. • Glacier Bay marmot • American peregrine falcon Landbirds • collared pika • Arctic peregrine falcon Seabirds Wildlife • American dipper • tundra hare • Peale’s peregrine falcon • short-tailed albatross • rusty blackbird • least weasel • northern saw-whet owl • marbled murrelet • Arctic warbler • little brown myotis • northern pygmy owl • Kittlitz’s murrelet • Aleutian tern Diversity • Prince of Wales spruce grouse • Keen’s myotis • northern hawk owl • olive-sided fl ycatcher • California myotis • western screech owl • black-legged kittiwake • various other songbirds • long-legged myotis • barred owl • common murre • silver-haired bat • short-eared owl • glaucous-winged gull Marine Mammals • various other small mammals • boreal owl • pelagic cormorant • bowhead whale • great gray owl • double-crested cormorant • North -

383 – with High Plant Cover and Low Human Disturbance (Allainé Et Al

DIET SELECTION OF THE ALPINE MARMOT (MARMOTA M. MARMOTA L.) IN THE PYRENEES I. GARIN1*, A. ALDEZABAL2, J. HERRERO3, A. GARCÍA-SERRANO4 & J.L. REMÓN4 RÉSUMÉ. — Sélection du régime alimentaire chez la Marmotte des Alpes (Marmota m. marmota L.) dans les Pyrénées.— Nous avons étudié de mai à septembre dans les Pyrénées occidentales la composition du régime alimentaire et la sélection des plantes dans deux groupes familiaux de Marmotte des Alpes Marmota m. marmota. La nourriture consommée a été déterminée par analyse des fèces et la sélection des plantes en comparant la composition des fèces au cortège de plantes disponibles dans la zone entourant les terriers des marmottes. La plupart des plantes disponibles n’appartenaient qu’à quelques familles dont l’abondance ne changea pas de manière remarquable durant les mois d’étude contrairement aux stades phénologiques des plantes. Les marmottes ont surtout consommé des végétaux consistant en une grande variété de feuilles, de fleurs et de graines de graminées et autres herbes, les feuilles de dicotylédones dominant nettement dans le régime. Les Légumineuses, Composées, Liliacées, Plantaginacées et Ombellifères étaient positivement sélectionnées ; les Labiées et les Rubiacées étaient évitées. Les fleurs étaient activement choisies sur la base de leur abondance relative et de leur phénologie. L’ingestion de proies animales (Arthropodes) a été confir- mée au début de la saison d’activité. SUMMARY. — We studied the diet composition and selection of plants in the Alpine marmot Marmota m. marmota of two family groups in the Western Pyrenees from May to September. The food consumed was determined by faecal analysis, and the plant selection was determined comparing the plant composition in faeces and plant availability in the area surrounding the marmot burrows, which was measured by the point- intercept method.