Hoary Marmot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ground Squirrels Live in Burrows That Are Litter Size: Five to Seven

L-1909 6/13 Controlling GROUND SQUIRRELDamage round squirrels are small, burrowing rodents earthen dikes with their burrows. Their burrow- found throughout the state, with the excep- ing and gnawing behavior also can cause damage G tion of extreme East Texas. There are five in irrigated areas. different species in Texas. These are the thirteen- lined ground squirrel, Mexican ground squirrel, spotted ground squirrel, rock squirrel, and the Texas antelope ground squirrel. Most ground Biology and Reproduction squirrels prefer grassy areas such as pastures, Rock squirrels golf courses, cemeteries and parks. Rock squir- Adult weight: 1½ to 1¾ pounds. rels are nearly always found in rocky cliffs, Total length: 18 to 21 inches. boulders, and canyon walls. The rock squirrel Color: Varies from dark gray to black. and thirteen-lined ground squirrel are the two species that most commonly cause damage by Tail: 7 to 10 inches, somewhat bushy. their burrowing and gnawing. Gestation period: Approximately 30 days. Ground squirrels live in burrows that are Litter size: Five to seven. usually 2 to 3 inches in diameter and 15 to 20 Number of litters: Possibly two per year, feet long. The burrow system usually has two usually born from April to August. entrances. Dirt piles around the entry holes are seldom evident. Rock squirrels and thirteen- Life span: 4 to 5 years. lined ground squirrels may hibernate during the Thirteen-lined ground squirrels coldest periods of winter. Adult weight: 5 to 9 ounces. Damage Total length: 7 to 12 inches. Ground squirrels normally do not cause Color: Light to dark brown with 13 stripes extensive damage in urban areas. -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

Vancouver Island Marmot

Vancouver Island Marmot Restricted to the mountains of Vancouver Island, this endangered species is one of the rarest animals in North America. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks move between colonies can have a profound one basket” situation puts the Vancouver impact on the entire population. Island Marmot at considerable risk of Vancouver Island Marmots have disap- extinction. peared from about two-thirds of their his- Why are Vancouver Island torical natural range within the past several What is their status? Marmots at risk? decades and their numbers have declined by urveys of known and potential colony he Vancouver Island Marmot exists about 70 percent in the last 10 years. The sites from 1982 through 1986 resulted in nowhere in the world except Vancouver 1998 population consisted of fewer than 100 counts of up to 235 marmots. Counts Island.Low numbers and extremely local- individuals, making this one of the rarest Srepeated from 1994 through 1998 turned Tized distribution put them at risk. Human mammals in North America. Most of the up only 71 to 103 animals in exactly the same activities, bad weather, predators, disease or current population is concentrated on fewer areas. At least 12 colony extinctions have sheer bad luck could drive this unique animal than a dozen mountains in a small area of occurred since the 1980s. Only two new to extinction in the blink of an eye. about 150 square kilometres on southern colonies were identified during the 1990s. For thousands of years, Vancouver Island Vancouver Island. Estimating marmot numbers is an Marmots have been restricted to small Causes of marmot disappearances imprecise science since counts undoubtedly patches of suitable subalpine meadow from northern Vancouver Island remain underestimate true abundance. -

Phylogeny, Biogeography and Systematic Revision of Plain Long-Nosed Squirrels (Genus Dremomys, Nannosciurinae) Q ⇑ Melissa T.R

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94 (2016) 752–764 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeny, biogeography and systematic revision of plain long-nosed squirrels (genus Dremomys, Nannosciurinae) q ⇑ Melissa T.R. Hawkins a,b,c,d, , Kristofer M. Helgen b, Jesus E. Maldonado a,b, Larry L. Rockwood e, Mirian T.N. Tsuchiya a,b,d, Jennifer A. Leonard c a Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, National Zoological Park, Washington DC 20008, USA b Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington DC 20013-7012, USA c Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC), Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics Group, Avda. Americo Vespucio s/n, Sevilla 41092, Spain d George Mason University, Department of Environmental Science and Policy, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 20030, USA e George Mason University, Department of Biology, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 20030, USA article info abstract Article history: The plain long-nosed squirrels, genus Dremomys, are high elevation species in East and Southeast Asia. Received 25 March 2015 Here we present a complete molecular phylogeny for the genus based on nuclear and mitochondrial Revised 19 October 2015 DNA sequences. Concatenated mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees were constructed to determine Accepted 20 October 2015 the tree topology, and date the tree. All speciation events within the plain-long nosed squirrels (genus Available online 31 October 2015 Dremomys) were ancient (dated to the Pliocene or Miocene), and averaged older than many speciation events in the related Sunda squirrels, genus Sundasciurus. -

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1965 Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel Donna Mae Balph Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Balph, Donna Mae, "Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel" (1965). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1552. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1552 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND COMMUNICATION IN THE UINTA GROUND SQUIRREL by Donna Mae Balph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Wildlife Biology Approved: Major Professor ~ &1 Gradua'te Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION GENERAL LIFE HISTORY 2 METHODS AND APPARATUS 7 RESULTS 1 0 Use of calls in interaction with conspeci fics 10 Chirp 10 Chirp by males 10 Chirp by females 1 7 Churr 22 Squeal 24 Squawk 24 Teeth clatter 31 Growl 34 Use of calls by juveniles 34 Comparison of chirp and churr 36 Use of calls in interaction with other species . 43 Reaction to airborne predators 43 Reaction to predators on ground 47 Reaction to snakes 52 DISCUSSION . 55 Unspecifi c ilEilur~-.jJl call s 55 Ease of location of calls 57 CONCLUSIONS 59 LITERATURE CITED 61 LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. -

A Review of Bristly Ground Squirrels Xerini and a Generic Revision in the African Genus Xerus

Mammalia 2016; 80(5): 521–540 Boris Kryštufek*, Ahmad Mahmoudi, Alexey S. Tesakov, Jan Matějů and Rainer Hutterer A review of bristly ground squirrels Xerini and a generic revision in the African genus Xerus DOI 10.1515/mammalia-2015-0073 Received April 28, 2015; accepted October 13, 2015; previously Introduction published online December 12, 2015 Bristly ground squirrels from the arid regions of Central Abstract: Bristly ground squirrels Xerini are a small rodent Asia and Africa constitute a coherent monophyletic tribe tribe of six extant species. Despite a dense fossil record the Xerini sensu Moore (1959). The tribe contains six species group was never diverse. Our phylogenetic reconstruction, in three genera of which Atlantoxerus and Spermophilop based on the analysis of cytochrome b gene and including sis are monotypic. The genus Xerus in its present scope all known species of Xerini, confirms a deep divergence (Thorington and Hoffmann 2005), consists of four species between the African taxa and the Asiatic Spermophilopsis. in three subgenera: X. inauris and X. princeps (subgenus Genetic divergences among the African Xerini were of a Geosciurus), X. rutilus (subgenus Xerus), and X. eryth comparable magnitude to those among genera of Holarc- ropus (subgenus Euxerus). Recent phylogenetic recon- tic ground squirrels in the subtribe Spermophilina. Evi- struction based on molecular markers retrieved Xerus to dent disparity in criteria applied in delimitation of genera be paraphyletic with respect to Atlantoxerus (Fabre et al. in Sciuridae induced us to recognize two genera formerly 2012), therefore challenging the suitability of the generic incorporated into Xerus. The resurrected genera (Euxerus arrangement of the group. -

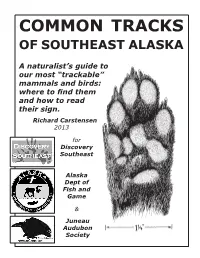

Common Tracks of Southeast Alaska

COMMON TRACKS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA A naturalist’s guide to our most “trackable” mammals and birds: where to find them and how to read their sign. Richard Carstensen 2013 for Discovery Southeast Alaska Dept of Fish and Game & Juneau Audubon Society TRACKING HABITATS muddy beaches stream yards & trails mudflat banks buildings keen’s mouse* red-backed vole* long-tailed vole* red squirrel beaver porcupine shrews* snowshoe hare* black-tailed deer domestic dog house cat black bear short-t. weasel* mink marten* river otter * Light-footed. Tracks usually found only on snow. ISBN: 978-0-9853474-0-6# 2013 text & illustrations © Discovery Southeast Printed by Alaska Litho Juneau, Alaska 1 CONTENTS DISCOVERY SOUTHEAST ........................................................... 2 ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME ............................... 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION ............................................ 5 TRACKING BASICS: LINGO, GAITS ......................................... 10 SCIENTIFIC NAMES ................................................................ 16 MAMMAL TRACK DESCRIPTIONS ............................................ 18 BIRD TRACK DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 35 AMPHIBIANS .......................................................................... 40 OTHER MAMMALS ................................................................... 41 OTHER BIRDS ......................................................................... 45 RECOMMENDED FIELD -

Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel Or Chipmunk? by Lynne Brosch

Who Is Your Pest? Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel or Chipmunk? by Lynne Brosch Recently as I went around the lake doing talks on pest management, I had several complaints about chipmunks. People describe a lot of digging and eating of plants by these chipmunks. As I began thinking about putting out some information on how to handle the situation I thought about the golden-mantled ground squirrel, I watched eating garden plants voraciously on the Baldwin Estate grounds just yesterday. Perhaps gardeners need to know who they are dealing with. The golden-mantled ground squirrel looks a lot like a chipmunk. It has a large white stripe bordered by black on each side. The main difference between this squirrel and a chipmunk is that its stripes don’t go all the way to the face and it is a slightly larger animal. It lives along the west coast in coniferous forests and mountainous areas. It likes to eat plants, seeds, nuts, fruit and some insects. It lives in an underground burrow usually near trees or logs. Chipmunks have very similar burrows. Most common in the Tahoe basin is the Lodgepole chipmunk. Fencing can be used to protect plants from squirrels and chipmunks, but has challenges in effectiveness because of the excellent digging and climbing skills exhibited by these garden pests. Hardware cloth may be used to exclude animals from flower beds with seeds and bulbs covered by the hardware cloth and all covered with soil. This method of prevention may prove less costly and time consuming than trapping. The most successful method for control of ground squirrels and chipmunks is the use of traps. -

North American Game Birds Or Animals

North American Game Birds & Game Animals LARGE GAME Bear: Black Bear, Brown Bear, Grizzly Bear, Polar Bear Goat: bezoar goat, ibex, mountain goat, Rocky Mountain goat Bison, Wood Bison Moose, including Shiras Moose Caribou: Barren Ground Caribou, Dolphin Caribou, Union Caribou, Muskox Woodland Caribou Pronghorn Mountain Lion Sheep: Barbary Sheep, Bighorn Deer: Axis Deer, Black-tailed Deer, Sheep, California Bighorn Sheep, Chital, Columbian Black-tailed Deer, Dall’s Sheep, Desert Bighorn Mule Deer, White-tailed Deer Sheep, Lanai Mouflon Sheep, Nelson Bighorn Sheep, Rocky Elk: Rocky Mountain Elk, Tule Elk Mountain Bighorn Sheep, Stone Sheep, Thinhorn Mountain Sheep Gemsbok SMALL GAME Armadillo Marmot, including Alaska marmot, groundhog, hoary marmot, Badger woodchuck Beaver Marten, including American marten and pine marten Bobcat Mink North American Civet Cat/Ring- tailed Cat, Spotted Skunk Mole Coyote Mouse Ferret, feral ferret Muskrat Fisher Nutria Fox: arctic fox, gray fox, red fox, swift Opossum fox Pig: feral swine, javelina, wild boar, Lynx wild hogs, wild pigs Pika Skunk, including Striped Skunk Porcupine and Spotted Skunk Prairie Dog: Black-tailed Prairie Squirrel: Abert’s Squirrel, Black Dogs, Gunnison’s Prairie Dogs, Squirrel, Columbian Ground White-tailed Prairie Dogs Squirrel, Gray Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Fox Squirrel, Ground Rabbit & Hare: Arctic Hare, Black- Squirrel, Pine Squirrel, Red Squirrel, tailed Jackrabbit, Cottontail Rabbit, Richardson’s Ground Squirrel, Tree Belgian Hare, European -

Action Plan for the Conservation of the Danube

Action Plan for the Conservation of the European Ground Squirrel Spermophilus citellus in the European Union EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2013 1. Compilers: Milan Janák (Daphne/N2K Group, Slovakia), Pavel Marhoul (Daphne/N2K Group, Czech Republic) & Jan Matějů (Czech Republic). 2. List of contributors Michal Adamec, State Nature Conservancy of the Slovak Republic, Slovakia Michal Ambros, State Nature Conservancy of the Slovak Republic, Slovakia Alexandru Iftime, Natural History Museum „Grigore Antipa”, Romania Barbara Herzig, Säugetiersammlung, Naturhistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria Ilse Hoffmann, University of Vienna, Austria Andrzej Kepel, Polish Society for Nature Conservation ”Salamandra”, Poland Yordan Koshev, Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Science, Bulgaria Denisa Lőbbová, Poznaj a chráň, Slovakia Mirna Mazija, Oikon d.o.o.Institut za primijenjenu ekologiju, Croatia Olivér Váczi, Ministry of Rural Development, Department of Nature Conservation, Hungary Jitka Větrovcová, Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, Czech Republic Dionisios Youlatos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece 3. Lifespan of plan/Reviews 2013 - 2023 4. Recommended citation including ISBN Janák M., Marhoul P., Matějů J. 2013. Action Plan for the Conservation of the European Ground Squirrel Spermophilus citellus in the European Union. European Commission. ©2013 European Communities Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Cover photo: Michal Ambros Acknowledgements for help and support: Ervín -

Convergent Evolution of Himalayan Marmot with Some High-Altitude Animals Through ND3 Protein

animals Article Convergent Evolution of Himalayan Marmot with Some High-Altitude Animals through ND3 Protein Ziqiang Bao, Cheng Li, Cheng Guo * and Zuofu Xiang * College of Life Science and Technology, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha 410004, China; [email protected] (Z.B.); [email protected] (C.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (Z.X.); Tel.: +86-731-5623392 (C.G. & Z.X.); Fax: +86-731-5623498 (C.G. & Z.X.) Simple Summary: The Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) lives on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and may display plateau-adapted traits similar to other high-altitude species according to the principle of convergent evolution. We assessed 20 species (marmot group (n = 11), plateau group (n = 8), and Himalayan marmot), and analyzed their sequence of CYTB gene, CYTB protein, and ND3 protein. We found that the ND3 protein of Himalayan marmot plays an important role in adaptation to life on the plateau and would show a history of convergent evolution with other high-altitude animals at the molecular level. Abstract: The Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana) mainly lives on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and it adopts multiple strategies to adapt to high-altitude environments. According to the principle of convergent evolution as expressed in genes and traits, the Himalayan marmot might display similar changes to other local species at the molecular level. In this study, we obtained high-quality sequences of the CYTB gene, CYTB protein, ND3 gene, and ND3 protein of representative species (n = 20) from NCBI, and divided them into the marmot group (n = 11), the plateau group (n = 8), and the Himalayan marmot (n = 1).