Reiniger's Carmen Cuts Her Own Capers Harriet Margolis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Some Critical Perspectives on Lotte Reiniger William Moritz [1996] 15](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3071/some-critical-perspectives-on-lotte-reiniger-william-moritz-1996-15-113071.webp)

Some Critical Perspectives on Lotte Reiniger William Moritz [1996] 15

"Animation: Art and Industry" ed. by Maureen Furniss, Indiana University 2Some CriticalPerspectives on Lotte Reiniger SomeCritical Perspectives onLotte Reiniger William Moritz [1996] otte Reiniger was bornin Berlin her first independent animation film, Das on 2June 1899. As a child, she Ornament des verliebten Herzens (Ornament Ldeveloped a facility withcutting of the Loving Heart), in the fall of 1919. paper silhouette figures, which had On the basis of the success of thisfilm, she become a folk-art formamong German got commercial workwith Julius women. As a teenager, she decided to Pinschewer’s advertising filmagency, pursue a career as an actress, and enrolled including an exquisite “reverse” silhouette in Max Reinhardt’s Drama School. She film, Das Geheimnis der Marquise (The began to volunteer as an extra for stage Marquise’s Secret), in which the elegant performances and movie productions, and white figures of eighteenth-century during the long waits between scenes and nobility (urging you to use Nivea skin takes, she would cut silhouette portraitsof cream!) seem like cameo or Wedgwood the stars, which she could sell to help pay images. These advertising films helped her tuition. The great actor-director Paul fund four more animated shorts: Amor und Wegener noticed not only the quality of das standhafte Liebespaar (Cupid and The the silhouettesshe made, but also her Steadfast Lovers, which combined incredible dexterity in cutting: holding the silhouettes with a live actor) in 1920, Hans scissors nearly still in her right hand and Christian Andersen’s Der fliegende Koffer moving the paper deftly in swift gestures (The Flying Suitcase) and Der Stern von thatuncannily formulated a complex Bethlehem (The Star of Bethlehem) in profile. -

Reiniger Research Proposal 10-29-17

RESURRECTING THE STUDY OF A FORGOTTEN ANIMATOR: A REOPENING OF THE CASE FOR LOTTE REINIGER Emily Rawson Loyola Marymount University Honors Program Abstract This proposal requests funding to access and view a series of historical German films and to purchase materials for the recreation of key sequences of the animated films of Lotte Reiniger, a historical German animator. From this work, two animated films will be made: a short narrative piece and a longer informational film to investigate and interpret Reiniger’s medium and artistic choices in the context of German expressionism. The goal of this work is to recognize Lotte Reiniger’s films as artistic achievements worthy of including Reiniger in academic discussions about contemporary innovative German filmmakers – discussions from which she is currently neglected because her work has been branded as impressive feats of craft rather than film art. Rawson !1 Introduction The profession of filmmaking splits itself between intersectional focuses on developing technology, earning revenue, pursuing art, and reflecting or even influencing the societies in which they are made.1 Recognizing these four distinct motives in making films, film historians can work to understand films both as accomplishments of innovation in the technical craft and as open texts better understood within the contexts of their crafting: the former interpretation requiring that historians master knowledge of the technology available and previous uses of cinematic techniques, and the latter requiring that historians acquaint -

Animating Silhouettes

BALL STATE UNIVERSITY Animating Silhouettes Honors College Senior Project Leslie West Fall 2007 ~f~ / /-Ie1f "07 , I ., : ,.' Abstract: .~ .. "~', J;tP'l'>' 1"'~"" \ This paper is a~~~fd of my experiences creating an animated movie of silhouettes, based upon the movies of Lotte Reiniger. It includes information about the artist that inspired this project, my processes, and related art forms. 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Prater, for his guidance throughout this project. All of the constructive criticism and suggestions were a very big help throughout the completion of this project. Also, I'd like to say a big thank you for the last few years of support as an academic advisor and professor. I'd also like to extend my thanks to Liz Boehm, Chris Penzenik, and Lauren West, for helping with this paper. I really appreciate the time you spent reviewing and editing with me. Your suggestions made this paper complete. Finally, I'd like to say a thank you again to Lauren West, for being my gopher while I studied abroad. This project was such a big process, and I literally couldn't have done this without you. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INSPIRATION: LOTTE REINIGER... ..................... ............ ABOUT THE ARTIST. HER FEA TURE FILM AND HER PROCESS ....... ................ , ............... OTHER SILHOUETTE ARTiSTS.......... .................. ..... ....... ... ......... .. ..... WAYANG-KULlT ........................................................................... HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN ....................................... -

Download File

Lotte Reiniger Lived: June 2, 1899 - June 19, 1981 Worked as: animator, assistant director, co-director, director, film actress, illustrator, screenwriter, special effects Worked In: Canada, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom: England by Frances Guerin, Anke Mebold Lotte Reiniger made over sixty films, of which eleven are considered lost and fifty to have survived. Of the surviving films for which she had full artistic responsibility, eleven were created in the silent period if the three-part Doktor Dolittle (1927-1928) is considered a single film. Reiniger is known to have worked on—or contributed silhouette sequences to—at least another seven films in the silent era, and a further nine in the sound era. Additionally, there is evidence of her involvement in a number of film projects that remained at conceptual or pre-production stages. Reiniger is best known for her pioneering silhouette films, in which paper and cardboard cut-out figures, weighted with lead, and hinged at the joints—the more complex the characters’ narrative role, the larger their range of movements, and therefore, the more hinges for the body—were hand-manipulated from frame to frame and shot via stop motion photography. The figures were placed on an animation table and usually lit from below. In some of her later sound films the figures were lit both from above and below, depending on the desired visual effect. Framed with elaborate backgrounds made from varying layers of translucent paper or colorful acetate foils for color films, Reiniger’s characters were created and animated with exceptional skill and precision. Reiniger’s early films ranged in length from brief shorts of less than 300 feet to Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed/The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1923-1926), a film that is arguably the first full-length animated feature and is thus considered to be among the milestones of cinema history. -

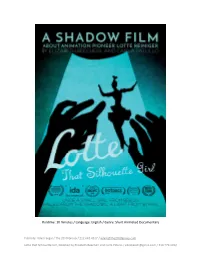

Short Animated Documentary

Runtime: 10 minutes / Language: English / Genre: Short Animated Documentary Publicity: Adam Segal / The 2050 Group / 212.642.4317 / [email protected] Lotte that Silhouette Girl, Directed by Elizabeth Beecherl and Carla Patullo / [email protected] / 310.779.1762 LOGLINE (25 words): Once a small girl, from Berlin, hailed from the shadows, a light from within. ALTERNATE LOGLINE (25 words): Once upon a time, long before Disney and other animation giants, Lotte Reiniger ignited the screen with shadows, light, and a pair of magical scissors. SHORT SYNOPSIS (59 words): Before Walt Disney, there was a trailblazing woman at the vanguard of animation. Influenced by folktales and legends, Lotte Reiniger was a tour de force of creativity and innovation: she invented the multiplane camera and created the oldest surviving animated feature. This stunning film explores the life and times of a woman who is finally being given her due. LONG SYNOPSIS (185 words): Once upon a time, long before Disney and the other animation giants, Lotte Reiniger ignited the screen with shadows, light, and a pair of magical scissors. And so with music, magic, and a stirring narration by Lotte herself, LOTTE THAT SILHOUETTE GIRL tells the largely unknown story of one of animations’ biggest influencers. Her unique style of storytelling and visual contrast inspired many, including modern day filmmakers Henry Selick, Anthony Lucas and many others. Lotte's 1926 film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed is the oldest surviving feature length animation, and she also invented the multi‐plane camera, both of which changed the field of animation forever. And sadly, both feats are often mistakenly credited to Walt Disney. -

March 2, 1978

IHE IHURSDA y IIEPORT CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY • MONTREAL • VOLUME 1, NUMBER 22 • MARCH 2, 1978 Senate approves,two 'colleges' Concordia Senate voted last Friday to establish a women's institute and a centre for mature students at an approximate cost of $68,000 a year each. Tomorrow (Friday, March 3), Senate is scheduled to meet at 10 am for a day-long session to debate and perhaps vote on the creation of a liberal arts college . and a religious college. The Senate vote recommends that the Concordia Board of Governors adopt the two resolutions which passed with over whelming majorities. If the Board passes the two resolutions when it meets 1 pm on March 9 then work can begin on the creation of "small units such as colleges" for this September. At last Friday's meeting, Senate officially received University Provost Robert Wall's report on "small units such More on Soviets at Loyo/,a, p. 4 as colleges". · Senate quickly passed over the Priori ties and Resource Allocation Committee Report, when Rector John O'Brien, Senate Resident fees to drop 20°/o chairman, suggested Senators keep the Residence fees will drop by 20% next that the 1977-78 budget was pre ared report in mind when discussing colleges. year as part of a campaign to attract more before he became residence director. Before Senate were proposals for four students to Loyola's Hingston and Langley Concordia residences operate on a "small units such as colleges". Dr. Wall Halls, residence airector David Chanter balanced budget. Operating funds must acted as chief spokesman, with proponents announced last week. -

Lotte Reiniger: the Fairy Tale Films

Our resources are designed to be used with selected film titles, which are available free for clubs at www.intofilm.org Film guide Lotte Reiniger: The Fairy Tale Films Germany, UK | 1922 - 1954 | Cert. PG | 197 mins Director: Lotte Reiniger Working in the early 20th century, German animator Lotte Reiniger is celebrated for her pioneering paper cut- out silhouette animation technique. In the 1930s she made a series of fairy tale films in this unique style bringing to life favourites like Cinderella, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. This is a collection of these short tales complete with wonderful soundtracks and charming narration. BFI © (1922) All rights reserved. You will like this film if you liked Talk about it (before the film) Frozen (2013, PG) What is a silhouette? Can you make one with your hands? List the types of characters you expect to find in a fairytale. Talk about it (after the film) • List the fairy tale characters that appear in these films. • Can you describe how the films look? Are they different to other animated films you’ve seen? • What do you notice about how the characters move across the screen? Does this remind you of anything? • How does the voice you hear in the films (called narration) help you Disney © (2013) All rights reserved. understand the story? What does this remind you of? Watch next • What type of ending do all the stories have? Is this surprising? Why? The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926, PG) • Choose your favourite film. In groups tell each other what message you think your favourite film is giving us. -

Work in Progress

JANN HAWORTH PROJECT AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR LIBERTY BLAKE MURAL COLLAGE ARTIST AND DESIGNER LYNN BLODGETT PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHER WORK IN PROGRESS Te Brigham Young University Museum of Art presents Work in Progress, a collaborative traveling exhibition that pays tribute to important women who have been catalysts for change, past and present. Artistic Director Jann Haworth, together with collage artist Liberty Blake, asked community members to join in creating stencils of signifcant women who have shaped our history. No stranger to transformative collaborations, Haworth worked with Peter Blake to create the Beatles’ iconic Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover in 1967 and later produced the SLC Pepper mural in downtown Salt Lake City in 2004, inviting members of the community to participate in the process. Haworth then began to conceive of a socially relevant and timely mural that would honor the countless achievements of women across disciplines. Driven by a desire to champion the critical successes of these women, Haworth organized a preliminary list. Seeking recommendations from museum visitors, friends, artists, social workers, colleagues, and government representatives, Haworth gradually generated a richly diverse compilation—and then invited local volunteers to make stencils of their personal favorites. Opposite the completed mural in this gallery are portraits of the volunteers taken by acclaimed photographer Lynn Blodgett, suggesting the enduring infuence of these dynamic women on contemporary society. First exhibited at Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City at the end of 2016, the murals then consisted of 7 panels, spanning 28 ft. in length. Haworth envisions an organic evolution of the project as each successive institution invites its community to add new stencils to the ever-growing mural. -

BFI FILM SALES CATALOGUE CONTENTS 2 4 Introduction

BFI FILM SALES CATALOGUE CONTENTS 2 4 Introduction 6 Recent Highlights 8 New FIlms 18 Animation 2018 22 Director Highlights 24 Alex Cox 26 Terence Davies’ Trilogy 28 Peter Greenaway 48 Derek Jarman 50 Ron Peck 54 Bill Douglas 56 Constantine Giannaris 76 Patrick Keiller’s Trilogy 86 Humphrey Jennings 34 Post-1960 Features 58 Post-1960 Features 66 Silent Film Restorations 72 Creative Documentaries 78 Documentaries 90 Free Cinema 94 Animation 96 Lotte Reiniger 100 The Quay Brothers 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The British Film Institute (BFI) is the lead body for film in the UK with the ambition to create a flourishing film environment in which innovation, opportunity and creativity can thrive by; connecting audiences to British and world cinema; preserving and restoring the most significant film collection in the world; championing emerging filmmakers; investing in creative and distinctive work; promoting British film and talent; growing the next generation of filmmakers and audiences. As part of the institute’s global mission, BFI Film Sales represents a collection of film and television content for sales and distribution across all media in international and domestic markets. This catalogue presents, in a non-exhaustive manner, the great wealth of titles we act on behalf of. These include works from the BFI Production (1951-2000) back-catalogue, independently represented contemporary and classic films, government film collections and thousands of titles from the BFI National Archive, including restorations of rediscovered masterpieces. The BFI also remain committed to continuing our support of the film and TV industry through clip and still sales, theatrical bookings and touring programmes and our teams are here to provide advice and further details on any titles from the collection. -

March 21 — 25, 2011

EASTMAN SCHOOL OF Music’s 7TH ANNUAL MARch 21 — 25, 2011 Sylvie Beaudette, Artistic Director Eun Mi Ko, Assistant Director All events are FREE and open to the public Eastman School of Music’s 7th Annual Women in Music Festival in collaboration with: Funding for the Women in Music Festival The Women in Music Festival and Hilary Tann’s residency are sponsored by: The Hanson Institute for American Music at the Eastman School of Music; the Neilly Lecture Series (River Campus Libraries); the Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender and Women’s Studies; Eastman’s departments of Chamber Music, Composition, and Piano, as well as the All-Events Committee; and the Dean of the Eastman School of Music. A Word from Douglas Lowry, Dean of the Eastman School of Music As it begins its seventh year, Eastman’s Women in Music Festival enjoys increasing and ever-widening success, and continues to highlight the achievements of women in all aspects of music. This is most visible in composition and performance, but women also play vital roles “behind the scenes” in teaching, scholarship, and administration. The work of women, whether well-known, brand-new, or sometimes hidden for centuries, has injected important content and energy into our historical con- sciousness, both at Eastman and in the larger musical world. In the words of our Women in Music Festival director, Sylvie Beaudette: “Eastman graduates are everywhere in the world; they will perform and teach music by women as a matter of course, because the music is good.” For this year’s festival, we welcome a distinguished guest: Hilary Tann, the Welsh- born composer who now teaches at Union College and whose music has been per- formed around the world. -

The Multiple Marginalization of Lotte Reiniger and the Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926)

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 National Identity, Gender, and Genre: The Multiple Marginalization of Lotte Reiniger and The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) K. Vivian Taylor University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Taylor, K. Vivian, "National Identity, Gender, and Genre: The Multiple Marginalization of Lotte Reiniger and The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926)" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3377 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationality, Gender, and Genre: The Multiple Marginalization of Lotte Reiniger and The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) by K. Vivian Taylor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Jerry Ball, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 31, 2011 Keywords: film history, animation studies, Disney myth, Lotte Reiniger, literary adaptation © Copyright 2011, K. Vivian Taylor DEDICATION For Joni Bernbaum and Judi McBride, who taught me that justice doesn't come from a courtroom, but it sure helps. For Margit and Dr. Sipiora, who fought the good fight. -

Emily Rawson the Return of Lotte Reiniger

Emily Rawson The Return of Lotte Reiniger Project Proposal 21 February 2019 Budget For this project, I request the funding: • $900 for flights to and from London* o I depart from either BWI or Dulles in Maryland (my hometown), to either London Heathrow, or the Dublin airport to catch a connecting flight to London • $150 for three nights’ stay in London** • $450 for viewing films at the British Film Institute and German Film Archives o Both the BFI and Wiesbaden archives charge researchers for screenings of rare films at hourly rates*** • $120 for flight from London to Paris* • $100 for a night in Paris** • $150 for a flight from Paris to Berlin* • $1500 for 11 nights’ stay in Germany** o Those nights will be split amongst various locations • $240 for longer distance trains between major German cities**** o Depending on competitive flight prices, a Eurail global pass might cover long distance travel in Germany, and travel from London to Paris and Paris to Berlin. • $260 for bus and public transit passes in London, Paris and Germany • $100 for museum passes o Museums that require passes include but are not limited to the British Film Institute, Filmmuseum of Dusseldorf, Frankfurt Film Institute, etc • $450 allowance for food (approximately $30 per day) • $240 for 1 year licensing of Adobe Software***** o This software package will give me access to necessary digital programs for collecting and processing photographic and video materials while in Germany, and these programs will also be essential for the crafting of the final film. The final total for this proposal is $4,660.