The Mechanisms of Derivatives Market Efficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

307439 Ferdig Master Thesis

Master's Thesis Using Derivatives And Structured Products To Enhance Investment Performance In A Low-Yielding Environment - COPENHAGEN BUSINESS SCHOOL - MSc Finance And Investments Maria Gjelsvik Berg P˚al-AndreasIversen Supervisor: Søren Plesner Date Of Submission: 28.04.2017 Characters (Ink. Space): 189.349 Pages: 114 ABSTRACT This paper provides an investigation of retail investors' possibility to enhance their investment performance in a low-yielding environment by using derivatives. The current low-yielding financial market makes safe investments in traditional vehicles, such as money market funds and safe bonds, close to zero- or even negative-yielding. Some retail investors are therefore in need of alternative investment vehicles that can enhance their performance. By conducting Monte Carlo simulations and difference in mean testing, we test for enhancement in performance for investors using option strategies, relative to investors investing in the S&P 500 index. This paper contributes to previous papers by emphasizing the downside risk and asymmetry in return distributions to a larger extent. We find several option strategies to outperform the benchmark, implying that performance enhancement is achievable by trading derivatives. The result is however strongly dependent on the investors' ability to choose the right option strategy, both in terms of correctly anticipated market movements and the net premium received or paid to enter the strategy. 1 Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction4 Problem Statement................................6 Methodology...................................7 Limitations....................................7 Literature Review.................................8 Structure..................................... 12 Chapter 2 - Theory 14 Low-Yielding Environment............................ 14 How Are People Affected By A Low-Yield Environment?........ 16 Low-Yield Environment's Impact On The Stock Market........ -

The Behaviour of Small Investors in the Hong Kong Derivatives Markets

Tai-Yuen Hon / Journal of Risk and Financial Management 5(2012) 59-77 The Behaviour of Small Investors in the Hong Kong Derivatives Markets: A factor analysis Tai-Yuen Hona a Department of Economics and Finance, Hong Kong Shue Yan University ABSTRACT This paper investigates the behaviour of small investors in Hong Kong’s derivatives markets. The study period covers the global economic crisis of 2011- 2012, and we focus on small investors’ behaviour during and after the crisis. We attempt to identify and analyse the key factors that capture their behaviour in derivatives markets in Hong Kong. The data were collected from 524 respondents via a questionnaire survey. Exploratory factor analysis was employed to analyse the data, and some interesting findings were obtained. Our study enhances our understanding of behavioural finance in the setting of an Asian financial centre, namely Hong Kong. KEYWORDS: Behavioural finance, factor analysis, small investors, derivatives markets. 1. INTRODUCTION The global economic crisis has generated tremendous impacts on financial markets and affected many small investors throughout the world. In particular, these investors feared that some European countries, including the PIIGS countries (i.e., Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain), would encounter great difficulty in meeting their financial obligations and repaying their sovereign debts, and some even believed that these countries would default on their debts either partially or completely. In response to the crisis, they are likely to change their investment behaviour. Corresponding author: Tai-Yuen Hon, Department of Economics and Finance, Hong Kong Shue Yan University, Braemar Hill, North Point, Hong Kong. Tel: (852) 25707110; Fax: (852) 2806 8044 59 Tai-Yuen Hon / Journal of Risk and Financial Management 5(2012) 59-77 Hong Kong is a small open economy. -

Global Derivatives Market

GLOBAL DERIVATIVES MARKET Aleksandra Stankovska European University – Republic of Macedonia, Skopje, email: aleksandra. [email protected] DOI: 10.1515/seeur-2017-0006 Abstract Globalization of financial markets led to the enormous growth of volume and diversification of financial transactions. Financial derivatives were the basic elements of this growth. Derivatives play a useful and important role in hedging and risk management, but they also pose several dangers to the stability of financial markets and thereby the overall economy. Derivatives are used to hedge and speculate the risk associated with commerce and finance. When used to hedge risks, derivative instruments transfer the risks from the hedgers, who are unwilling to bear the risks, to parties better able or more willing to bear them. In this regard, derivatives help allocate risks efficiently between different individuals and groups in the economy. Investors can also use derivatives to speculate and to engage in arbitrage activity. Speculators are traders who want to take a position in the market; they are betting that the price of the underlying asset or commodity will move in a particular direction over the life of the contract. In addition to risk management, derivatives play a very useful economic role in price discovery and arbitrage. Financial derivatives trading are based on leverage techniques, earning enormous profits with small amount of money. Key words: financial derivatives, leverage, risk management, hedge, speculation, organized exchange, over- the counter market. 81 Introduction Derivatives are financial contracts that are designed to create market price exposure to changes in an underlying commodity, asset or event. In general they do not involve the exchange or transfer of principal or title (Randall, 2001). -

Derivatives Market Structure 2020

Q1Month 2020 2015 Cover Headline Here (Title Case)Derivatives Market CoverStructure subhead here (sentence 2020case) I In partnership with DATA | ANALYTICS | INSIGHTS CONTENTS 2 Executive Summary 3 Methodology Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Capital, Libor and UMR The global derivatives market has undergone tremendous change over the past decade and, by most measures, has come out more 6 Market Structure: Potential for robust and efficient than ever. Increased transparency, more central Change clearing and vastly improved technology for trading, clearing and risk- 9 Understanding Derivatives End Users managing everything from futures to swaps to options has created 11 The Client to Clearer Relationship an environment in which nearly 80% of the market participants in this study believe liquidity in 2020 will only continue to improve. 13 The Sell-Side Perspective 16 Looking Forward To understand more deeply where we’ve been and where the derivatives market is headed, Greenwich Associates conducted a study in partnership with FIA, an association that represents banks, brokers, exchanges, and other firms in the global derivatives markets. The study gathered insights from nearly 200 derivatives market participants—traders, brokers, investors, clearing firms, exchanges, and clearinghouses—examining derivatives product usage, how they manage their counterparty relationships, their expectations for regulatory change, and more. The results painted a picture of an industry with the appetite and Managing Director opportunity for growth, but also one with challenges many are eager Kevin McPartland is to see overcome. The approaching Libor transition, continued rollout the Head of Research of uncleared margin rules, ongoing concern about capital requirements, for Market Structure and Technology at and a renewed focus on clearinghouse “skin in the game” are on the the Firm. -

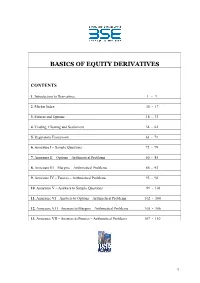

Basics of Equity Derivatives

BASICS OF EQUITY DERIVATIVES CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Derivatives 1 - 9 2. Market Index 10 - 17 3. Futures and Options 18 - 33 4. Trading, Clearing and Settlement 34 - 62 5. Regulatory Framework 63 - 71 6. Annexure I – Sample Questions 72 - 79 7. Annexure II – Options – Arithmetical Problems 80 - 85 8. Annexure III – Margins – Arithmetical Problems 86 - 92 9. Annexure IV – Futures – Arithmetical Problems 93 - 98 10. Annexure V – Answers to Sample Questions 99 - 101 11. Annexure VI – Answers to Options – Arithmetical Problems 102 - 104 12. Annexure VI I– Answers to Margins – Arithmetical Problems 105 - 106 13. Annexure VII – Answers to Futures – Arithmetical Problems 107 - 110 1 CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION TO DERIVATIVES The emergence of the market for derivative products, most notably forwards, futures and options, can be traced back to the willingness of risk-averse economic agents to guard themselves against uncertainties arising out of fluctuations in asset prices. By their very nature, the financial markets are marked by a very high degree of volatility. Through the use of derivative products, it is possible to partially or fully transfer price risks by locking- in asset prices. As instruments of risk management, these generally do not influence the fluctuations in the underlying asset prices. However, by locking in asset prices, derivative products minimize the impact of fluctuations in asset prices on the profitability and cash flow situation of risk-averse investors. 1.1 DERIVATIVES DEFINED Derivative is a product whose value is derived from the value of one or more basic variables, called bases (underlying asset, index, or reference rate), in a contractual manner. -

Inflation Derivatives: Introduction One of the Latest Developments in Derivatives Markets Are Inflation- Linked Derivatives, Or, Simply, Inflation Derivatives

Inflation-indexed Derivatives Inflation derivatives: introduction One of the latest developments in derivatives markets are inflation- linked derivatives, or, simply, inflation derivatives. The first examples were introduced into the market in 2001. They arose out of the desire of investors for real, inflation-linked returns and hedging rather than nominal returns. Although index-linked bonds are available for those wishing to have such returns, as we’ve observed in other asset classes, inflation derivatives can be tailor- made to suit specific requirements. Volume growth has been rapid during 2003, as shown in Figure 9.4 for the European market. 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 Jul 01 Jul 02 Jul 03 Jan 02 Jan 03 Sep 01 Sep 02 Mar 02 Mar 03 Nov 01 Nov 02 May 01 May 02 May 03 Figure 9.4 Inflation derivatives volumes, 2001-2003 Source: ICAP The UK market, which features a well-developed index-linked cash market, has seen the largest volume of business in inflation derivatives. They have been used by market-makers to hedge inflation-indexed bonds, as well as by corporates who wish to match future liabilities. For instance, the retail company Boots plc added to its portfolio of inflation-linked bonds when it wished to better match its future liabilities in employees’ salaries, which were assumed to rise with inflation. Hence, it entered into a series of 1 Inflation-indexed Derivatives inflation derivatives with Barclays Capital, in which it received a floating-rate, inflation-linked interest rate and paid nominal fixed- rate interest rate. The swaps ranged in maturity from 18 to 28 years, with a total notional amount of £300 million. -

EQUITY DERIVATIVES Faqs

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SECURITIES MARKETS SCHOOL FOR SECURITIES EDUCATION EQUITY DERIVATIVES Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Authors: NISM PGDM 2019-21 Batch Students: Abhilash Rathod Akash Sherry Akhilesh Krishnan Devansh Sharma Jyotsna Gupta Malaya Mohapatra Prahlad Arora Rajesh Gouda Rujuta Tamhankar Shreya Iyer Shubham Gurtu Vansh Agarwal Faculty Guide: Ritesh Nandwani, Program Director, PGDM, NISM Table of Contents Sr. Question Topic Page No No. Numbers 1 Introduction to Derivatives 1-16 2 2 Understanding Futures & Forwards 17-42 9 3 Understanding Options 43-66 20 4 Option Properties 66-90 29 5 Options Pricing & Valuation 91-95 39 6 Derivatives Applications 96-125 44 7 Options Trading Strategies 126-271 53 8 Risks involved in Derivatives trading 272-282 86 Trading, Margin requirements & 9 283-329 90 Position Limits in India 10 Clearing & Settlement in India 330-345 105 Annexures : Key Statistics & Trends - 113 1 | P a g e I. INTRODUCTION TO DERIVATIVES 1. What are Derivatives? Ans. A Derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset. The underlying asset can be equity shares or index, precious metals, commodities, currencies, interest rates etc. A derivative instrument does not have any independent value. Its value is always dependent on the underlying assets. Derivatives can be used either to minimize risk (hedging) or assume risk with the expectation of some positive pay-off or reward (speculation). 2. What are some common types of Derivatives? Ans. The following are some common types of derivatives: a) Forwards b) Futures c) Options d) Swaps 3. What is Forward? A forward is a contractual agreement between two parties to buy/sell an underlying asset at a future date for a particular price that is pre‐decided on the date of contract. -

Liquidity Effects in Options Markets: Premium Or Discount?

Liquidity Effects in Options Markets: Premium or Discount? PRACHI DEUSKAR1 2 ANURAG GUPTA MARTI G. SUBRAHMANYAM3 March 2007 ABSTRACT This paper examines the effects of liquidity on interest rate option prices. Using daily bid and ask prices of euro (€) interest rate caps and floors, we find that illiquid options trade at higher prices relative to liquid options, controlling for other effects, implying a liquidity discount. This effect is opposite to that found in all studies on other assets such as equities and bonds, but is consistent with the structure of this over-the-counter market and the nature of the demand and supply forces. We also identify a systematic factor that drives changes in the liquidity across option maturities and strike rates. This common liquidity factor is associated with lagged changes in investor perceptions of uncertainty in the equity and fixed income markets. JEL Classification: G10, G12, G13, G15 Keywords: Liquidity, interest rate options, euro interest rate markets, Euribor market, volatility smiles. 1 Department of Finance, College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 304C David Kinley Hall, 1407 West Gregory Drive, Urbana, IL 61801. Ph: (217) 244-0604, Fax: (217) 244-9867, E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Department of Banking and Finance, Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44106-7235. Ph: (216) 368-2938, Fax: (216) 368-6249, E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Department of Finance, Leonard N. Stern School of Business, New York University, 44 West Fourth Street #9-15, New York, NY 10012-1126. Ph: (212) 998-0348, Fax: (212) 995-4233, E- mail: [email protected]. -

Introduction to Options

Introduction to Options 2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. What are options? ........................................................................................ 4 1.1 What is an option? ................................................................................... 5 Description of options................................................................................... 6 2.1 How does an option work? ...................................................................... 7 Contract specifications ................................................................................. 8 3.1 Standardisation ....................................................................................... 9 3.2 Types of options ...................................................................................... 9 3.3 Settlement type upon exercise .............................................................. 10 3.4 Underlying values .................................................................................. 10 3.5 Currency ................................................................................................ 10 3.6 Option premium..................................................................................... 10 3.7 Adjustment ............................................................................................ 11 What can options be used for? ................................................................... 12 4.1 Making a profit ...................................................................................... 13 4.2 -

OTC Derivatives the New Cost of Trading

OTC Derivatives The new cost of trading To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Contents Executive summary 1 Data sources and methodology 3 Costs for OTC derivative transactions that will need to be centrally cleared 5 Costs for OTC derivative transactions that will not need to be centrally cleared 9 What do firms need to be doing now? 13 What will the market look like post-reform? 14 Endnotes 15 Glossary of acronyms 16 References 17 Contacts 18 B To start a new section, hold down the apple+shift keys and click to release this object and type the section title in the box below. Executive summary Over-the-counter (OTC) derivative markets are subject to significant change as global regulatory commitments originating in 2009 take effect. In Europe, the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) requires standardised OTC derivatives to be cleared through central counterparties (CCPs); derivatives which cannot be cleared to be subject to bilateral margining arrangements and a strengthened operational risk framework; and OTC and exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs) to be reported to a trade repository (TR). In addition, the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) increase capital requirements for both cleared and non-cleared OTC derivatives. The scope of the reform is far reaching and covers the five main asset classes: interest rate, credit, foreign exchange (FX), commodity and equity.1 It is clear that costs will increase as a result of these reforms, but the question is by how much and where the burden will fall. -

Derivatives in Financial Market Development

Working paper Derivatives in Financial Market Development Rangarajan K. Sundaram September 2012 Derivatives in Financial Market Development Rangarajan K. Sundaram Stern School of Business, New York University http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/ rsundara e 13 September 2012 Contents Executive Summary ii 1 Introduction 2 2 The World Derivatives Market 2 2.1 Basic Derivative Instruments . 2 2.2 Market Size and Growth . 4 2.3 EmergingMarketsversusAdvancedEconomies . 7 3 Uses of Derivatives 9 4 The Potential Risks in Derivatives Usage 14 4.1 Barings Bank . 15 4.2 Metallgesellschaft . 16 4.3 Amaranth ..................................... 16 4.4 AracruzCellulose.................................. 17 4.5 AIG......................................... 18 4.6 Heeding the Lessons? . 19 5 Derivatives in the Indian Context: Some Comments 20 6 Regulation and its Challenges 26 A Derivatives Instruments 30 A.1 Forwards ...................................... 30 A.2 Futures....................................... 31 A.3 Swaps ....................................... 32 A.4 Options....................................... 32 A.5 CreditDerivatives ................................. 33 1 Executive Summary Derivatives are financial instruments whose payo↵s derive from other, more primitive financial variables such as a stock price, a commodity price, an index level, an interest rate, or an exchange rate. The world market for derivatives is an immense one. The notion amount outstanding in the over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives market worldwide exceeds $640 trillion,withacollective gross market value of over $27 trillion. The exchange-traded market has another $60 trillion in outstanding notional. The growth of derivatives usage over the last two decades has been rapid in both advanced economies and emerging markets; in both OTC contracts and those that are exchange-traded; and across all underlying classes, including interest-rate, currency, equity, and the most recent addition, credit. -

Inflation Derivatives

Inflation Derivatives Graduation Thesis Financial Engineering and Management A research on the implementation of inflation derivatives within pension funds Supervisors: Dr. D.Y. Dupont Dr. R. A. M. G. Joosten Dr. B. Roorda Drs. P. Bajema Author: C.F.A.R. Wanningen Company: Blue Sky Group Date: July 2007 Preface his thesis about inflation derivatives is the result of a six-month research which started in February and ended in July at pension fund provider Blue TSky Group. During this period I conducted a literature research on inflation linked products and developed a pricing model. Moreover I visited investment banks in London and the Euromoney Inflation Linked Products Conference 2007 in Frankfurt. The visits provided me with valuable information insights and business experience. Furthermore conversations with specialists working at Blue Sky Group and investment banks helped me to understand how inflation linked products are traded in the marketplace. By writing this preface I would gladly grasp the opportunity to thank persons who made a contribution to this thesis. From the University of Twente I would like to thank Dr. D.Y. Dupont, Dr. R.A.M.G. Joosten and Dr. B. Roorda. Dr. Dupont supervised the research and gave information insights during the first months. Dr. Roorda supervised the research throughout the whole period and initiated useful discussions on inflation. Dr. Joosten supervised the research during the last months and gave supportive suggestions on writing a thesis. From Blue Sky Group I would like to give thanks to Drs. P. Bajema, Drs. J.F. van Halewijn and A.A.M.