Tajikistan Unravelled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: the Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

Connections: The Quarterly Journal ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. 1 (2018): 21-41 https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.17.1.02 Research Article Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: The Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Kemel Toktomushev University of Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, http://www.ucentralasia.org Abstract: Despite the prevalence of works on the ‘discourses of danger’ in the Ferghana Valley, which re-invented post-Soviet Central Asia as a site of intervention, the literature on the conflict potential in the cross-border areas of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan is fairly limited. Yet, the number of small-scale clashes and tensions on the borders of the Batken and Isfara regions has been growing steadily. Accordingly, this work seeks to con- tribute to the understanding of the conflict escalations in the area and identify factors that aggravate tensions between the communities. In par- ticular, this article focuses on four variables, which exacerbate tensions and hinder the restoration of a peaceful social fabric in the Batken-Isfara region: the unresolved legacies of the Soviet past, inefficient use of natu- ral resources, militarization of borders, and lack of evidence-based poli- cymaking. Keywords: Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ferghana, conflict, bor- ders. Introduction The significance and magnitude of violence and conflict potential in the con- temporary Ferghana Valley has been identified as one of the most prevalent themes in the study of post-Soviet Central Asia. This densely populated region has been long portrayed as a site of latent inter-ethnic conflict. Not only is the Ferghana Valley a region, where three major ethnic groups—Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks—co-exist in a network of interdependent communities, sharing buri- Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Creative Commons Academies and Security Studies Institutes BY-NC-SA 4.0 Kemel Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. -

Tajikistan 2013 Human Rights Report

TAJIKISTAN 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tajikistan is an authoritarian state that President Emomali Rahmon and his supporters, drawn mainly from one region of the country, dominated politically. The constitution provides for a multi-party political system, but the government obstructed political pluralism. The November 6 presidential election lacked pluralism, genuine choice, and did not meet international standards. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The most significant human rights problems included torture and abuse of detainees and other persons by security forces; repression of political activism and restrictions on freedoms of expression and the free flow of information, including the repeated blockage of several independent news and social networking websites; and poor religious freedom conditions as well as violence and discrimination against women. Other human rights problems included arbitrary arrest; denial of the right to a fair trial; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; prohibition of international monitor access to prisons; limitations on children’s religious education; corruption; and trafficking in persons, including sex and labor trafficking. Officials in the security services and elsewhere in the government acted with impunity. There were very few prosecutions of government officials for human rights abuses. The courts convicted one prison official for abuse of power, and three others were under investigation for human rights abuses. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life In July and August 2012, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the media reported that the government or its agents were responsible for injuring and killing civilians during security operations in Khorugh, Gorno-Badakhshon Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), after the killing of Major General Abdullo Nazarov, the head of the regional branch of the State Committee for National Security (GKNB). -

Central Asia the Caucasus

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS No. 2(44), 2007 CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS Journal of Social and Political Studies 2(44) 2007 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 1 No. 2(44), 2007FOUNDED AND PUBLISHEDCENTRAL ASIA AND BYTHE CAUCASUS INSTITUTE INSTITUTE O OR CENTRAL ASIAN AND STRATEGIC STUDIES O CAUCASIAN STUDIES THE CAUCASUS Registration number: 620720-0459 Registration number: M-770 State Administration for Ministry of Justice of Patents and Registration of Sweden Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press®. SWEDEN Registration number: 556699-5964 Journal registration number: 23 614 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden E d i t o r i a l C o u n c i l Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council ISMAILOV Tel./fax: (994 - 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Murad ESENOV Editor-in-Chief Tel./fax: (46) 920 62016 E-mail: [email protected] Jannatkhan Executive Secretary (Baku, Azerbaijan) EYVAZOV Tel./fax: (994 - 12) 499 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Timur represents the journal in Kazakhstan (Astana) SHAYMERGENOV Tel./fax: (+7 - 701) 531 61 46 E-mail: [email protected] Leonid represents the journal in Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek) BONDARETS Tel.: (+996 - 312) 65-48-33 E-mail: [email protected] Jamila MAJIDOVA represents the journal in Tajikistan (Dushanbe) Tel.: (992 - 917) 72 81 79 E-mail: [email protected] Farkhad represents the journal in Uzbekistan (Tashkent) TOLIPOV Tel.: (9987-1) 125 43 22 E-mail: [email protected] Aghasi YENOKIAN represents the journal in Armenia (Erevan) Tel.: (374 - 1) 54 10 22 E-mail: [email protected] -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

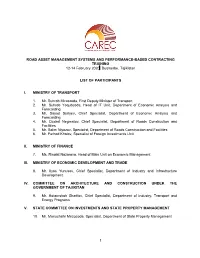

ROAD ASSET MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS and PERFORMANCE-BASED CONTRACTING TRAINING 12-14 February 2020Dushanbe, Tajikistan

ROAD ASSET MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS AND PERFORMANCE-BASED CONTRACTING TRAINING 12-14 February 2020Dushanbe, Tajikistan LIST OF PARTICIPANTS I. MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT 1. Mr. Suhrob Mirzozoda, First Deputy Minister of Transport 2. Mr. Suhrob Yoqubzoda, Head of IT Unit, Department of Economic Analysis and Forecasting 3. Mr. Sayod Suriyev, Chief Specialist, Department of Economic Analysis and Forecasting 4. Mr. Qudrat Negmatov, Chief Specialist, Department of Roads Construction and Facilities 5. Mr. Salim Niyozov, Specialist, Department of Roads Construction and Facilities 6. Mr. Farhod Kholov, Specialist of Foreign Investments Unit II. MINISTRY OF FINANCE 7. Ms. Risolat Nazarova, Head of Main Unit on Economic Management III. MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND TRADE 8. Mr. Ilyos Yunusov, Chief Specialist, Department of Industry and Infrastructure Development IV. COMMITTEE ON ARCHITECTURE AND CONSTRUCTION UNDER THE GOVERNMENT OF TAJIKITAN 9. Mr. Hotamshoh Sharifov, Chief Specialist, Department of Industry, Transport and Energy Programs V. STATE COMMITTEE ON INVESTMENTS AND STATE PROPERTY MANAGEMENT 10. Mr. Manuchehr Mirzozoda, Specialist, Department of State Property Management 1 VI. STATE UNITARY ENTERPRISE “DESIGN INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE” 11. Mr. Anvar Soirov, Engineer, Unit of Roads Design VII. STATE ENTERPRISES ON ROAD FACILITIES MANAGEMENT AND LOGISTIC SERVICE (under the Ministry of Transport) 12. Mr. Ismoilbek Odinaev, Head of Production and Technical Unit, State Enterprise “Road Department of Gissar Region” 13. Mr. Umed Ismoilov, Chief Engineer, State Enterprise on Road Maintenance of Gissar City 14. Mr. Jamshed Jobirov, Chief Engineer, State Enterprise on Road Maintenance of Varzob District 15. Mr. Odil Negmatov, Chief Engineer, State Enterprise on Road Maintenance of Fayzabad District 16. Mr. -

Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central

MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2012 MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), within the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and in Pakistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions that shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the customs offices of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the World Customs Office, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Natascha Eichinger (Consultant) Platon Nozadze (Consultant) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Shaukat Ullah Khan (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) A. -

Humanitarian Aid in Favour of the Population of Tajikistan Affected by Floods and Landslides

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HUMANITARIAN AID OFFICE (ECHO) Emergency Humanitarian Aid Decision 23 02 01 Title: Humanitarian aid in favour of the population of Tajikistan affected by floods and landslides Location of operation: TAJIKISTAN Amount of Decision: Euro 350,000 Decision reference number: ECHO/TJK/BUD/2004/02000 Explanatory Memorandum 1 - Rationale, needs and target population. 1.1. - Rationale: On 13 and 14 July, torrential rains accompanied by heavy winds and landslides resulted in flooding in the Varzob district of Tajikistan, causing first of all, substantial damage to infrastructure. The major Dushanbe-Anzob-Istarafshan road was severely affected at several points and key bridges were destroyed or damaged. Although flooding is a normal phenomenon in Tajikistan at this time of year, the water levels this year have been much higher than in previous years. In addition to the damage to infrastructure, the floods have caused severe problems for the water supply to the capital, Dushanbe. The Varzob river which provides up to 60% of the city’s water supply, was highly polluted by landslides. Dushanbe’s water system, which is in terrible condition following years of neglect, is unable to cope. On 14 July, tap water was deemed unfit for human consumption and recommendations were made not to touch the contaminated water. Water supplies were rapidly shut down, with consequently over half of the 600,000 population in the capital having no access to water at all. Despite the warnings there is a serious risk that many people will become infected with disease through collecting and using unsafe water. From 15 July water has been provided by authorities from 44 water trucks. -

Analysis of the Situation on Inclusive Education for People with Disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the Results of the Baseline Research

Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok» April - July 2018 Analysis of the situation on inclusive education for people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the results of the baseline research 1 EXPRESSION OF APPRECIATION A basic study on the inclusive education of people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan (RT) conducted by the Public Organization Disabled Women's League “Ishtirok”. This study was conducted under financial support from ASIA SOUTH PACIFIC ASSOCIATION FOR BASIC AND ADULT EDUCATION (ASPBAE) The research team expresses special thanks to the Executive Office of the President of the RT for assistance in collecting data at the national, regional, and district levels. In addition, we express our gratitude for the timely provision of data to the Centre for adult education of Tajikistan of the Ministry of labor, migration, and employment of population of RT, the Ministry of education and science of RT. We express our deep gratitude to all public organizations, departments of social protection and education in the cities of Dushanbe, Bokhtar, Khujand, Konibodom, and Vahdat. Moreover, we are grateful to all parents of children with disabilities, secondary school teachers, teachers of primary and secondary vocational education, who have made a significant contribution to the collection of high-quality data on the development of the situation of inclusive education for persons with disabilities in the country. Research team: Saida Inoyatova – coordinator, director, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Salomat Asoeva – Assistant Coordinator, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Larisa Alexandrova – lawyer, director of the Public Foundation “Your Choice”; Margarita Khegay – socio-economist, candidate of economic sciences. -

Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Jacob Zenn and Kathleen Kuehnast This report offers perspectives on the national and regional dynamics of violent extremism with respect to Kyrgyzstan. Derived from a study supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) to explore the potential for violent extremism in Central Asia, it is based on extensive interviews and a Preventing Violent countrywide Peace Game with university students at Kyrgyz National University in June 2014. Extremism in Kyrgyzstan ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jacob Zenn is an analyst on Eurasian and African affairs, a legal adviser on international law and best practices related to civil society and freedom of association, and a nonresident research Summary fellow at the Center of Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies in China, the Center of Security Programs in Kazakhstan, • Kyrgyzstan, having twice overthrown autocratic leaders in violent uprisings, in 2005 and again and The Jamestown Foundation in Washington, DC. Dr. Kathleen in 2010, is the most politically open and democratic country in Central Asia. Kuehnast is a sociocultural anthropologist and an expert on • Many Kyrgyz observers remain concerned about the country’s future. They fear that underlying Kyrgyzstan, where she conducted field work in the early 1990s. An adviser on the Central Asia Fellows Program at the socioeconomic conditions and lack of public services—combined with other factors, such as Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington drug trafficking from Afghanistan, political manipulation, regional instability in former Soviet University, she is a member of the Council on Foreign Union countries and Afghanistan, and foreign-imported religious ideologies—create an envi- Relations and has directed the Center for Gender and ronment in which violent extremism can flourish. -

"A New Stage of the Afghan Crisis and Tajikistan's Security"

VALDAI DISCUSSION CLUB REPORT www.valdaiclub.com A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY Akbarsho Iskandarov, Kosimsho Iskandarov, Ivan Safranchuk MOSCOW, AUGUST 2016 Authors Akbarsho Iskandarov Doctor of Political Science, Deputy Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Acting President of the Republic of Tajikistan (1990–1992); Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Tajikistan; Chief Research Fellow of A. Bahovaddinov Institute of Philosophy, Political Science and Law of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Kosimsho Iskandarov Doctor of Historical Science; Head of the Department of Iran and Afghanistan of the Rudaki Institute of Language, Literature, Oriental and Written Heritage of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Tajikistan Ivan Safranchuk PhD in Political Science; associate professor of the Department of Global Political Processes of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO-University) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia; member of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy The views and opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Contents The growth of instability in northern Afghanistan and its causes ....................................................................3 Anti-government elements (AGE) in Afghan provinces bordering on Tajikistan .............................................5 Threats to Central Asian countries ........................................................................................................................7 Tajikistan’s approaches to defending itself from threats in the Afghan sector ........................................... 10 A NEW STAGE OF THE AFGHAN CRISIS AND TAJIKISTAN’S SECURITY The general situation in Afghanistan after two weeks of fierce fighting and not has been deteriorating during the last few before AGE carried out an orderly retreat. -

LITACA-II MTE Final Report.Pdf

Mid-Term Evaluation Report Livelihood Improvement in Tajik – Afghan Cross Border Areas (LITACA-II) Report Information Report Title: Mid-Term Evaluation of Livelihood Improvement in Tajik- Afghan Cross-Border Areas; LITACA Phase II (2018 – 2020) Evaluation Team: Dilli Joshi, Independent Evaluation Specialist Ilhomjon Aliev, National Evaluation Specialist Field Mission: 4–29 February, 2020 Table of Contents Abbreviations Executive summary .............................................................................................................................. i 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 LITACA-II Goals, outcomes and outputs ........................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Theory of Change ..................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Objectives of the LITACA-II Mid-Term Evaluation ......................................................... 5 1.4 Purpose of the Mid-Term Evaluation ................................................................................. 5 1.5 Scope of the Mid-Term Evaluation ...................................................................................... 5 1.6 Organisation of the Mid-Term Evaluation ......................................................................... 5 2. Evaluation Approach and Methodology.................................................................................