Outcomes Evaluation Report UNDP Communities Program in Tajikistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: the Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

Connections: The Quarterly Journal ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. 1 (2018): 21-41 https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.17.1.02 Research Article Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: The Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Kemel Toktomushev University of Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, http://www.ucentralasia.org Abstract: Despite the prevalence of works on the ‘discourses of danger’ in the Ferghana Valley, which re-invented post-Soviet Central Asia as a site of intervention, the literature on the conflict potential in the cross-border areas of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan is fairly limited. Yet, the number of small-scale clashes and tensions on the borders of the Batken and Isfara regions has been growing steadily. Accordingly, this work seeks to con- tribute to the understanding of the conflict escalations in the area and identify factors that aggravate tensions between the communities. In par- ticular, this article focuses on four variables, which exacerbate tensions and hinder the restoration of a peaceful social fabric in the Batken-Isfara region: the unresolved legacies of the Soviet past, inefficient use of natu- ral resources, militarization of borders, and lack of evidence-based poli- cymaking. Keywords: Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ferghana, conflict, bor- ders. Introduction The significance and magnitude of violence and conflict potential in the con- temporary Ferghana Valley has been identified as one of the most prevalent themes in the study of post-Soviet Central Asia. This densely populated region has been long portrayed as a site of latent inter-ethnic conflict. Not only is the Ferghana Valley a region, where three major ethnic groups—Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks—co-exist in a network of interdependent communities, sharing buri- Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Creative Commons Academies and Security Studies Institutes BY-NC-SA 4.0 Kemel Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Jacob Zenn and Kathleen Kuehnast This report offers perspectives on the national and regional dynamics of violent extremism with respect to Kyrgyzstan. Derived from a study supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) to explore the potential for violent extremism in Central Asia, it is based on extensive interviews and a Preventing Violent countrywide Peace Game with university students at Kyrgyz National University in June 2014. Extremism in Kyrgyzstan ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jacob Zenn is an analyst on Eurasian and African affairs, a legal adviser on international law and best practices related to civil society and freedom of association, and a nonresident research Summary fellow at the Center of Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies in China, the Center of Security Programs in Kazakhstan, • Kyrgyzstan, having twice overthrown autocratic leaders in violent uprisings, in 2005 and again and The Jamestown Foundation in Washington, DC. Dr. Kathleen in 2010, is the most politically open and democratic country in Central Asia. Kuehnast is a sociocultural anthropologist and an expert on • Many Kyrgyz observers remain concerned about the country’s future. They fear that underlying Kyrgyzstan, where she conducted field work in the early 1990s. An adviser on the Central Asia Fellows Program at the socioeconomic conditions and lack of public services—combined with other factors, such as Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington drug trafficking from Afghanistan, political manipulation, regional instability in former Soviet University, she is a member of the Council on Foreign Union countries and Afghanistan, and foreign-imported religious ideologies—create an envi- Relations and has directed the Center for Gender and ronment in which violent extremism can flourish. -

Mercuryaddressing Primary Mercury Mining in Kyrgyzstan

The use of mercury is being reduced throughout the world due to its effects on human health and the environment. Certain forms of mercury and its compounds can damage neurological development and affect internal organs. Mercury can spread far and wide through air and water. It is Khaidarkan ingested by fish and other marine life, Addressing primary where it becomes concentrated as it moves up the food chain. mercury mining mercury in Kyrgyzstan There is now only one known mercury mine in the world which continues to sell its output abroad: Khaidarkan, in the remote mountains of southern Kyrgyzstan. What will happen to this “kombinat” is still far from clear. For the international community, continuing mercury mining raises significant concerns. Limiting mercury supply is one of the key elements to any comprehensive global approach to address mercury. www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel.: +254 20 762 1234 Fax: +254 20 762 3927 e-mail: [email protected] www.unep.org Produced by Zoï Environment Network www.zoinet.org This is a joint publication by the United Nations Environment Pro- gramme (UNEP) and the United Nations Institute of Training and Re- search (UNITAR) produced by Zoï Environment Network. The project to address primary Mercury Mining in Kyrgyzstan has been generously supported by the Governments of Switzerland, the United States of America and Norway. Printed on 100 % recycled paper at Imprimerie Nouvelle Gonnet, F-01303 Belley, France Copyright © 2009 ISBN: 978-82-7701-071-7 Cover artwork: Mural in the palace of culture, Khaidarkan This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form for A climate Neutral publication educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from The production and transport of each copy of this booklet has re- the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is leased about 0.4 kilogram’s of CO2-equivalent into the atmosphere. -

Annual Report

FUNDED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IMPLEMENTED BY THE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME With financial support from the Russian Federation ANNUAL REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS OF THE PROJECT “LIVELIHOOD IMPROVEMENT OF RURAL POPULATION IN 9 DISTRICTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN” FROM JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 2017 Dushanbe 2017 1 Russian Federation-UNDP Trust Fund for Development (TFD) Project Annual Narrative and Financial Progress Report for January 1 – December 31, 2017 Project title: "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan" Project ID: 00092014 Implementing partner: United Nations Development Programme, Tajikistan Project budget: Total: 6,700,000 USD TFD: Government of the Russian Federation: 6,700,000 USD Project start and end date: November 2014 – December 2017 Period covered in this report: 1st January to 31st December 2017 Date of the last Project Board 17th January 2017 meeting: SDGs supported by the project: 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Please provide a short summary of the results, highlighting one or two main achievements during the period covered by the report. Outline main challenges, risks and mitigation measures. The project "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan", is funded by the Government of the Russian Federation, and implemented by UNDP Communities’ Program in the Republic of Tajikistan through its regional offices. Project target areas are Isfara, Istaravshan, Ayni, Penjikent in Sughd region; Vose and Temurmalik in Khatlon region; Rasht, Tojikobod and Lakhsh (Jirgatal) in the Districts of Republican Subordination (DRS). The main objective of the project is to ensure sustainable local economic development of the target districts of Tajikistan. -

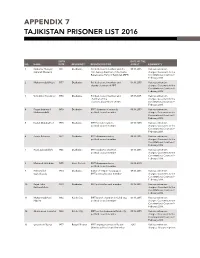

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

RGP O2 Eval Report Final.Pdf

! ! Evaluation Output 2 Rural Growth Programme UNDP Republic of Tajikistan Evaluation Report Kris B. Prasada Rao Alisher Khaydarov Aug 2013 ! ! ! List%of%acronyms,%terminology%and%currency%exchange%rates% Acronyms AFT Aid for Trade AKF Aga Khan Foundation AO Area Office BEE Business Enabling Environment CDP Community Development Plan CO Country Office CP Communities Programme DCC Tajikistan Development Coordination Council DDP District Development Plan DFID Department for International Development DIM Direct Implementation Modality DP Development Plan GDP Gross Domestic Product GIZ Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GREAT Growth in the Rural Economy and Agriculture of Tajikistan HDI Human Development Index ICST Institute for Civil Servants Training IFC International Finance Corporation, the World Bank IOM International Organisation for Migration JDP Jamoat Development Plan LED Local Economic Development LEPI Local Economic Performance Indicator M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEDT Ministry of Economic Development and Trade MC Mahalla Committee MoF Ministry of Finance MoU Memorandum of Understanding MSDSP Mountain Societies Development Support Programme MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise NDS National Development Strategy NIM National Implementation Modality O2 Output 2, RGP O&M Operation and Maintenance ODP Oblast Development Plan: Sughd Oblast Social Economic Plan OECD/DAC Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Co-operation Directorate PEI UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative PPD Public-Private -

Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Corridors 2, 3, and 5 (Obigarm-Nurobod) Road Project: Report and Recommendation of Th

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 52042-001 November 2019 Proposed Grant Republic of Tajikistan: Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Corridors 2, 3, and 5 (Obigarm–Nurobod) Road Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 17 October 2019) Currency unit – somoni (TJS) TJS1.00 = $0.1032 $1.00 = TJS9.6911 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AIIB – Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank CAREC – Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation CSC – construction supervision consultant EBRD – European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EMP – environmental management plan GAP – gender action plan km – kilometer LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan m – meter MOT – Ministry of Transport OFID – OPEC Fund for International Development PAM – project administration manual PBM – performance-based maintenance PCC – project coordinating committee PIURR – Project Implementation Unit for Roads Rehabilitation PMC – project management consultant PPRA – project procurement risk assessment NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. Vice-President Shixin Chen, Operations 1 Director General Werner Liepach, Central and West Asia Department (CWRD) Director Dong-Soo Pyo, Transport and Communications Division, CWRD Team leader Kamel Bouhmad, Transport Specialist, CWRD -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT Public Disclosure Authorized CENTRAL ASIA ROAD LINKS – REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized (EIA) Public Disclosure Authorized Date: August 27, 2014 Rehabilitation and Upgrade of Road Sections in Sugd Region - Republic of Tajikistan Environmental Impact Assessment Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Background 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Project Background 6 1.3 Background of the Study Road 7 2. Legal, Policy and Administrative Framework 7 2.1 Country Policies and Administrative Framework 8 2.2 Assessment Requirements of the World Bank 12 2.3 Recommended Categorization of the Project 13 2.4 World Bank Safeguards Requirements 14 2.4.1 Environmental Assessment (OP/BP 4.01) 14 2.4.2 Natural Habitats (OP/BP 4.04) 14 2.4.3 Physical Cultural Resources (OP/BP 4.11) 14 2.4.4 Forests (OP/BP 4.36) 15 2.4.5 Involuntary Resettlement (OP/BP 4.12) 15 3. Methodology of the Environmental Impact Assessment 15 4. Description of the Project 16 4.1 General 16 4.2 Description of the Sections to be financed under the Project and potential Impacts 16 4.3 Need for the Project – the “Do – Nothing – Option” 19 4.4 Traffic Volumes and Transport Modes 20 4.5 Borrow Pits and Quarries - Construction Material 20 5. Description of the Existing Environment 22 5.1 Physical Characteristics 22 5.1.1 Topography, Geology and Soils 22 5.1.2 Landslides, Avalanches and Earthquake Activity 23 5.1.3 Erosion 24 5.1.4 Climate and Air Quality 25 5.1.5 Hydrology and Water Quality 26 5.2 Biological Resources 27 5.2.1 Flora 27 D:\48439_CAR_TAJ\04_Reports\05 EIA\48439_Final EIA CARs-2 270808_en.docx Page 2 Rehabilitation and Upgrade of Road Sections in Sugd Region - Republic of Tajikistan Environmental Impact Assessment 5.2.2 Fauna 28 5.2.3 Protected Areas 28 5.3 Socio – Economic Characteristics 29 5.3.1 Industry 29 5.3.2 Agriculture 29 5.3.3 Population and Demographics 29 5.3.4 Livelihood and Poverty 29 5.3.5 Cultural Heritage 30 6. -

Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan

Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan May 2012 This study was conducted with financial support from the International Organization for Migration Development Fund. In its activities, IOM believes that a humane and orderly migration responds to the interests of migrants and society, as a whole. As a leading intergovernmental organization IOM is working with its partners in the international community, guided by the following objectives: to promote the solution of urgent migration problems, improve understanding of the problems in the area of migration; encourage social and economic development through migration; assert the dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Mission in the Republic of Tajikistan Dushanbe, 734013 22-A Vtoroy Proezd, Azizbekov Street Telephone: +992 (37) 221-03-02 Fax: +992 (37) 251-00-62 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iom.tj © 2012 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any way - through electronic and mechanical means, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in this report represent those of individual authors and unless clearly labeled as such do not rep- resent the opinions of the International Organization for Migration. Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan May 2012 Saodat Olimova Muzaffar Olimov ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors of this report express their deepest gratitude to Zeynal Hajiyev, Chief of IOM Mission in Tajikistan and the employees of the IOM country office, especially Moyonsho Mahmadbekov, Patrik Shirak and Zohir Navjavonov for their invaluable advice on improving the structure and content of this report. -

Succession of Multiple Disasters Humanitarian Bulletin

Humanitarian Bulletin South Caucasus and Central Asia Issue 03 | 01 January – 30 June 2014 In this issue Seasonal disasters in Tajikistan P.1 Tensions in the Fergana Valley P.2 HIGHLIGHTS Drought looming over Kyrgyzstan P.3 Multiple disasters hit Tajikistan Massive landslide in Georgia P.4 Tense situation on the Credit: UNOCHA Kyrgyz-Tajik border Drought in Kyrgyzstan might drive up food prices Main trends from 2013 continue Floods in Kazakhstan Region stilll vulnerable to seasonal disasters and man-made crises The first half of 2014 saw main trends from 2013 continue: the year started off with a FIGURES cross-border conflict in the tumultuous Fergana Valley that climaxed in May, with # of Syrian 16,000 residents of the Tajik enclave Vorukh clashing with adjacent Kyrgyz villages. The official Armenian sides once again show interest in peaceful mutually-beneficial resolution to the tensions; refugees however, results of the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan agreement on cooperation signed in on 28 Affected pop. in 7,400 May are yet to be seen. Tajikistan In Tajikistan, a series of small- to medium-scale seasonal disasters struck several # of disasters in 21 Tajikistan districts, killing 20 people and causing agricultural and infrastructural damage. The Government of Tajikistan demonstrated its increased capacity to coordinate relief efforts # of disasters in 82 Kyrgyzstan with humanitarian partners and to quickly respond to emergencies. In Armenia, humanitarian partners continued monitoring the refugee situation and CAUCASUS provided help to the most vulnerable in surviving cold winter. Some 16,000 Syrian Armenian refugees are reported to have entered the country since the start of the crisis.